I recently found myself lying flat on my back in the cramped confines of an fMRI machine at a research center in Austin, Texas, wearing a pair of ill-fitting scrubs. “The things I do for television,” I mused.

Anybody who has undergone an MRI or fMRI scan will attest to how noisy it is; when electric currents swirl, a strong magnetic field is created, resulting in a thorough scan of your brain. On this occasion, though, I was given a pair of specialized earbuds that started playing clips from The Wizard of Oz audiobook. Despite this, I could only just make out the loud cranking of the mechanical magnets.

Why?

Using the same artificial intelligence system that drives the ground-breaking chatbot ChatGPT, neuroscientists at the University of Texas in Austin have discovered a way to translate brain scans into speech.

The development could fundamentally alter how those who are mute can communicate. It’s just one of many ground-breaking uses for AI that have emerged in recent months as the field continues to improve and appears destined to influence every aspect of our lives and society.

Alexander Huth, an assistant professor of neurology and computer science at the University of Texas in Austin, explained to me, “So, we don’t want to use the phrase mind reading. “We believe it conjures up abilities that are actually beyond our reach.”

Huth volunteered to participate in the study and spent more than 20 hours inside an fMRI scanner listening to audio samples as the device took precise images of his brain.

After studying his brain activity and the sounds he was hearing,

an artificial intelligence model was eventually able to anticipate the words he was hearing just by keeping an eye on his brain.

The researchers employed the GPT-1 language model from San Francisco-based startup OpenAI, which was created using a sizable collection of books and websites. The model discovered how sentences are put together through the analysis of all this data, which is essentially how people speak and think.

The scientists programmed the AI to examine Huth’s and other participants’ brain activity when they listened to particular words. After some time, the AI had picked up enough knowledge to be able to infer from the brain activity of Huth and others what they were listening to or watching.

I was in the machine for less than a half-hour, and as I feared, the AI was unable to discern that I had been listening to the passage of The Wizard of Oz audiobook that talked about Dorothy traveling the yellow brick road.

Huth was listening to the same audio, but because the AI model had been trained on his brain, it could accurately predict certain passages of the audio.

Although the technology is still in its infancy and has immense potential, some people may find solace in the restrictions. Yet, AI is unable to simply understand our minds.

Huth stated that the actual potential use of this is in aiding those who are unable to communicate.

He and other UT Austin researchers think the ground-breaking technology may someday be utilized by patients with “locked-in” syndrome, stroke victims, and others whose brains are still functioning but who are mute.

“Ours is the first instance where we show that without a brain operation, we can get this level of precision. Therefore, we believe that this is sort of the first step toward genuinely assisting those who are mute without requiring them to have neurosurgery,” he said.

Undoubtedly excellent news for those suffering from crippling illnesses, groundbreaking medical advancements nevertheless raise concerns about how the technology might be used in contentious situations.

Could it be used to force a prisoner to confess? Or to reveal our darkest, most secretive secrets?

The quick response, according to Huth and his coworkers, is no – not right now.

To begin with, fMRI machines must be used for brain scans, hours must be spent training AI on a subject’s brain, and, according to Texas researchers, subjects must provide their assent. The brain scans won’t be successful if a person purposefully avoids listening to noise or is preoccupied with anything else.

According to Jerry Tang, the lead author of a report outlining his team’s findings that was released earlier this month, “we believe that everyone’s brain data should be kept private.” One of the last remaining unexplored areas of our privacy is our brains.

According to Tang, “obviously there are concerns that brain decoding technology could be used in dangerous ways.” The researchers prefer the term “brain decoding” to “mind reading.”

“Mind reading makes me think of the idea of getting at the minor ideas you don’t want to admit to, minor like reactions to things. And I don’t believe anyone has suggested that we can actually accomplish that using this method, said Huth. “What we can acquire are the broad concepts you’re considering. If you’re attempting to tell a story to yourself, we can kind of get at the story that someone else is telling you.

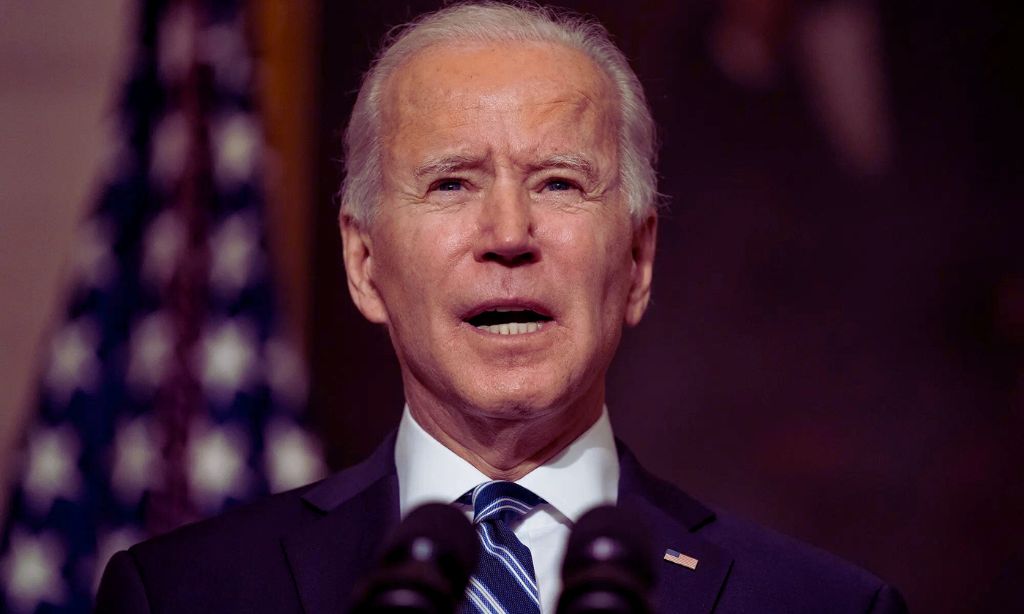

The creators of generative AI systems, including Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, flocked to Capitol Hill this week to testify before a Senate committee in response to lawmakers’ worries about the dangers posed by the potent technology. Altman cautioned that the unfettered growth of AI might “cause significant harm to the world” and encouraged legislators to enact rules to allay worries.

Tang told CNN that politicians need to take “mental privacy” seriously to preserve “brain data”—our thoughts—in the age of AI, echoing the AI warning. These are two of the more apocalyptic expressions I’ve heard.

Although the technology now only functions in a relatively small number of situations, this may not always be the case.

“It’s important not to get a false sense of security and think that things will be this way forever,” Tang cautioned. “As technology advances, it may affect both our ability to decode and whether decoders need human cooperation.”