Scientists temporarily hooked a pig’s kidney to a human body and watched it begin to function, a modest step toward using animal organs for life-saving transplants, which has been a goal of scientists for decades.

Pigs have been the focus of current research to address organ scarcity, but there are a number of roadblocks, including sugar in pig cells that is foreign to the human body and causes organ rejection. This experiment used a kidney from a gene-edited animal that was designed to remove the sugar and escape an immune system attack.

To study the pig kidney for two days, surgeons linked it to a pair of major blood veins outside the body of a deceased recipient. The kidney completed its job — filtering trash and producing urine — and did not cause rejection.

Dr. Robert Montgomery, who headed the surgery team at NYU Langone Health last month, stated, “It had perfectly normal function.” “It didn’t have the same kind of quick rejection that we were afraid about.”

Dr. Andrew Adams of the University of Minnesota Medical School, who was not involved in the study, called it “a tremendous milestone.” “We’re headed in the right path,” will comfort patients, researchers, and regulators.

The fantasy of animal-to-human transplants, also known as xenotransplantation, dates back to faltering attempts to utilize animal blood for transfusions in the 17th century. By the twentieth century, doctors started attempting organ transplants from baboons into people, with notable success in the case of Baby Fae, a dying newborn who survived 21 days with a baboon heart.

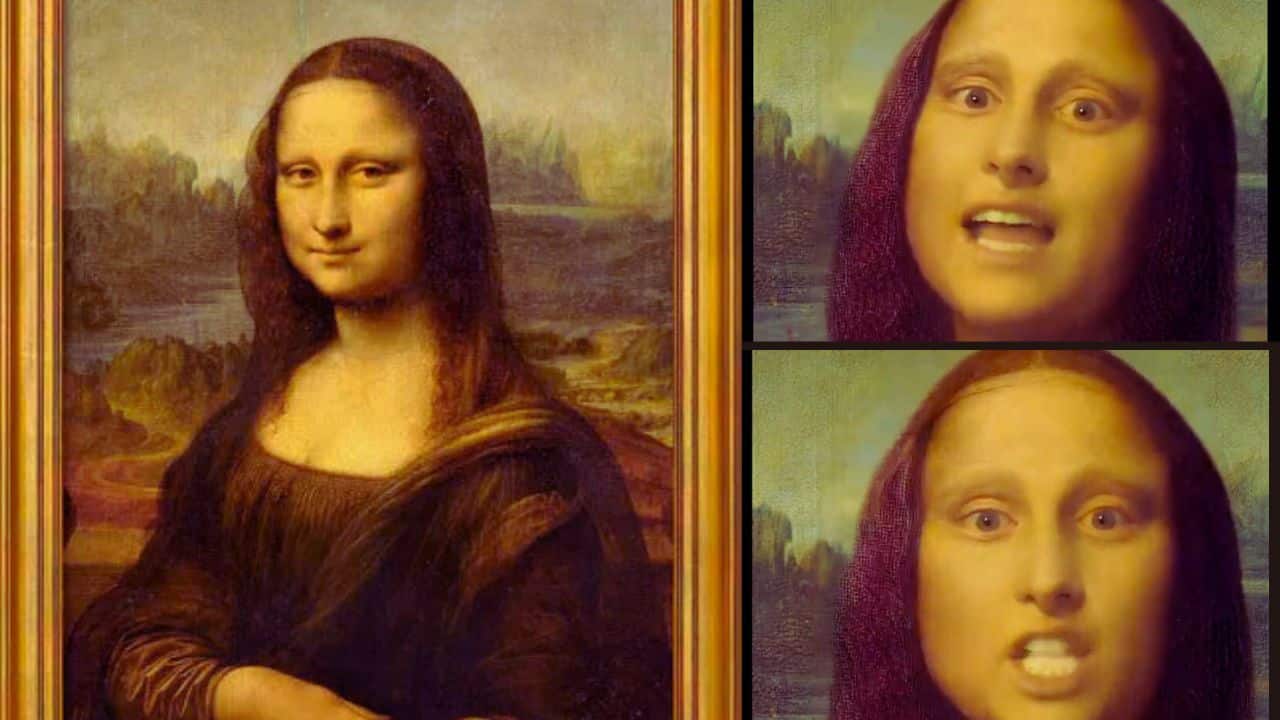

Pig Kidney Transplant in a Human

With little lasting results and much public outcry, scientists resorted to pigs to bridge the species gap, meddling with their genomes.

Compared to primates and apes, pigs have an edge. Because they are grown for food, utilizing them for organs has fewer ethical issues. Pigs have large litters, short gestation periods, and organs that are similar to those seen in humans.

Human heart valves have been effectively used in pigs for decades. Heparin, a blood thinner, is made from the intestines of pigs. Burns are treated with pigskin grafts, and Chinese surgeons have utilized pig corneas to restore vision.

After her family agreed to the experiment, researchers at NYU kept a deceased woman’s body on a ventilator. The woman wanted to donate her organs, but they weren’t fit for standard donation.

According to Montgomery, the family believed “there was a chance that something positive may arise from this gift.”

Montgomery had a transplant three years ago, a human heart from a hepatitis C donor because he was willing to accept any organ. “I was one of those persons waiting in an ICU, not knowing if an organ would arrive in time,” he explained.

Several biotech firms are competing to create transplantable pig organs to help alleviate human organ scarcity. In the United States, more than 90,000 patients are waiting for a kidney transplant. Every day, 12 people pass away while waiting.

Revivicor, a subsidiary of United Therapeutics, which engineered the pig and its cousins, a herd of 100 raised in closely controlled conditions at an Iowa facility, has won the advance.

The pigs are missing a gene that makes alpha-gal, a chemical that triggers an immunological response in humans.

The Food and Drug Administration declared the gene change in Revivicor pigs safe for human food and pharmaceuticals in December.

However, the FDA stated that further documentation would be required before pig organs could be transplanted into real humans.

In a statement, United Therapeutics CEO Martine Rothblatt stated, “This is a crucial step forward in achieving the promise of xenotransplantation, which will save thousands of lives each year in the not-too-distant future.”

Tests on nonhuman primates and a human body experiment last month, according to experts, open the way for the first experimental pig kidney or heart transplants in living people in the coming years.

Some people believe that raising pigs to be organ donors is unethical, but if concerns about animal welfare can be addressed, it may become more acceptable, according to Karen Maschke, a research scholar at the Hastings Center who will help develop ethics and policy recommendations for the first clinical trials funded by the National Institutes of Health.

“Then there’s the question of whether we should do this just because we can?” Maschke remarked.