In 2026, governments are moving from scattered digital health pilots to something bigger and harder: building national digital health records that work for everyone, including people living far from major hospitals. This shift is not just about going paperless. It is about digital health sovereignty, meaning a country’s ability to control its health data, the systems that store it, the rules that govern it, and the vendors that build it.

Rural economies sit at the center of this story. Rural clinics often face weak connectivity, limited staff, and fragile supply chains. At the same time, rural communities carry a heavy burden of maternal and child health needs, infectious disease risks, and fast-growing chronic conditions. When national records are designed for city hospitals first, rural patients end up invisible or excluded. When national records are designed for rural realities, they can become the most powerful equity tool in public health.

This article explains why 2026 is a turning point, what national digital health records actually require, and how countries can implement systems that strengthen trust, protect rights, and improve care delivery in rural settings.

Why 2026 Is A Turning Point

Many countries spent the last decade experimenting with digital health through apps, donor-funded pilots, and isolated electronic medical record systems. These efforts created learning, but they also created fragmentation. Patients gained multiple IDs across different programs. Facilities collected data that could not be shared. Ministries struggled to see a full picture of population health.

In 2026, the strategic emphasis is changing. Governments and health systems increasingly want national-scale infrastructure that can support continuity of care, public health surveillance, and smarter financing. They want records that follow people across clinics and across time. They also want tighter governance around where data lives, who accesses it, and how vendors are held accountable.

Several forces are pushing this shift. Cybersecurity threats are rising. Public trust is fragile. Health budgets are under pressure, and waste becomes more visible when data is fragmented. At the same time, digital identity systems and payment rails are becoming common, which makes health systems ask a logical next question. If we can identify people reliably for services, why can we not also carry their health history safely?

For rural economies, the moment is urgent. Climate shocks, migration, and economic instability can disrupt care pathways. A portable, secure, patient-centered record can prevent treatment gaps when people move for work, relocate during floods, or seek care outside their home district.

What Digital Health Sovereignty Means In Practice

Digital health sovereignty is often misunderstood as a purely technical issue. In reality, it is a governance and capability issue first.

A sovereign digital health system can do the following:

- Set clear rules on data access, consent, and accountability

- Decide where data is stored and under what conditions it can cross borders

- Require interoperability standards so systems can exchange information safely

- Avoid vendor lock-in by enforcing portability and transparent contracts

- Audit usage and investigate misuse with real consequences

- Build local capacity to operate and improve systems over time

This matters because health data is among the most sensitive data a country can hold. It reveals intimate life details. It can be misused for discrimination, political targeting, or financial fraud if governance is weak. A sovereignty approach treats health data as critical national infrastructure, not just a byproduct of software.

In 2026, digital health sovereignty is becoming a guiding principle for policy choices. Some countries prioritize strong local hosting rules. Others focus on strict access controls and independent oversight. Many aim for a blend, including clear standards for cloud providers, encryption, and auditability.

What National Digital Health Records Actually Are

People use many terms loosely, so it helps to define what “national digital health records” can mean.

A national digital health record system is not always a single centralized database. It is typically a national capability that lets authorized providers find, read, and add to a person’s health history across facilities. It can be built as a centralized record, a federated model, or a hybrid.

Here are common components that sit behind a national record experience:

- Identity and matching so records belong to the right person

- Provider and facility registries so systems know who is allowed to access data

- Data standards and interoperability rules so systems can exchange information

- Consent and access management so patients and policy rules control visibility

- Audit logs so every access can be traced and investigated

- Clinical data services that store or reference health events over time

If these building blocks are missing, a “national record” becomes a slogan. It turns into disconnected portals and partial databases that create more administrative work and less clinical value.

Rural Economies Change The Requirements

A record system that works in a capital city can fail instantly in rural areas. Rural constraints are not minor. They define the system.

Connectivity Constraints

Many rural clinics have unstable internet, limited bandwidth, and power outages. If the system requires continuous connectivity, staff will abandon it. If the system supports offline capture with later synchronization, adoption rises sharply.

Workforce Constraints

Rural health workers often manage high patient loads with minimal support. If data entry takes too long, they will skip steps or create shadow notes on paper. A rural-ready record must reduce burden, not add it.

Language And Literacy Constraints

Patients may not read the official language fluently. Many will not have smartphones. That means the model must support assisted access through community health workers, kiosks, and printed summaries with secure verification options.

Mobility And Documentation Constraints

People move for seasonal work, disasters, or family needs. Names can be spelled differently across records. IDs can be missing or inconsistent. Matching must handle uncertainty without creating exclusion.

A 2026 system that claims to serve rural economies must solve these realities upfront. Otherwise, it will digitize the urban minority and leave the rural majority behind.

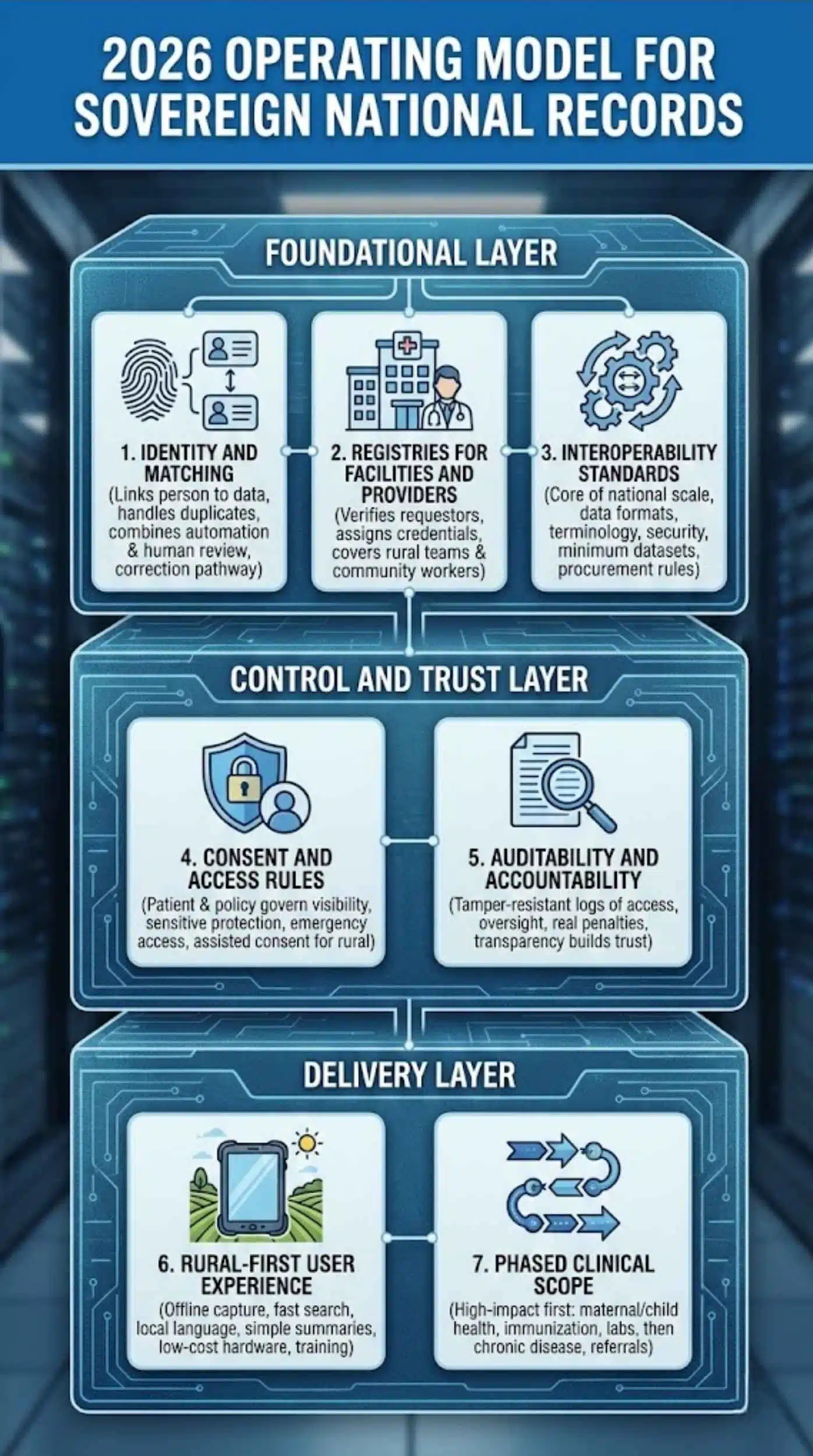

The 2026 Operating Model For Sovereign National Records

A strong national program in 2026 looks less like an app and more like a set of rails. These rails support many workflows, many providers, and many future upgrades.

Below is a practical model that aligns with digital health sovereignty and rural usability.

Foundational Layer

1. Identity And Matching

This layer links a person to their health data. It can use national ID, a health-specific ID, or multiple identifiers. It must handle duplicates and errors safely, because mislinking records can harm patients.

The best systems combine automation and safeguards. They use matching algorithms, but they also allow human review when confidence is low. They provide a correction pathway so patients can fix mistakes.

2. Registries For Facilities And Providers

A national record only works when the system can verify who is asking for data. A provider registry assigns credentials. A facility registry confirms that a clinic is legitimate and licensed.

In rural settings, the registry must also cover outreach teams and community health workers. Otherwise, rural services remain outside the system.

3. Interoperability Standards

Interoperability is not optional. It is the core of national scale. Standards cover data formats, terminology, transport, and security. They also define minimum datasets for key programs like immunization, maternal care, and chronic disease.

A 2026 strategy should define a national interoperability policy, a conformance testing process, and procurement rules that require compliance.

Control And Trust Layer

4. Consent And Access Rules

Consent design varies by country, but the principle is consistent. Patients and policy must govern visibility. Sensitive categories may require extra protection. Emergency access may be allowed under strict logging and review.

In rural settings, consent must be usable without smartphones. Assisted consent workflows should be available, with safeguards to prevent coercion.

5. Auditability And Accountability

Audit logs should record who accessed what, when, and why. Logs should be tamper-resistant. Oversight bodies should investigate suspicious patterns. Penalties must be real, not symbolic.

This is where digital health sovereignty becomes visible to the public. People trust systems when they see enforcement and transparency.

Delivery Layer

6. Rural-First User Experience

A sovereign system is not only policy. It is also daily workflow.

A rural-first experience includes:

- Offline capture with queued sync

- Fast search and minimal clicks

- Local language support

- Simple summaries for quick clinical decisions

- Low-cost hardware requirements

- Training materials that match local realities

7. Phased Clinical Scope

Trying to digitize every clinical detail at once often fails. A phased plan focuses on high-impact areas first. Many programs start with maternal and child health, immunization, and essential labs, then expand to chronic disease management and referrals.

This approach produces value quickly while building capacity.

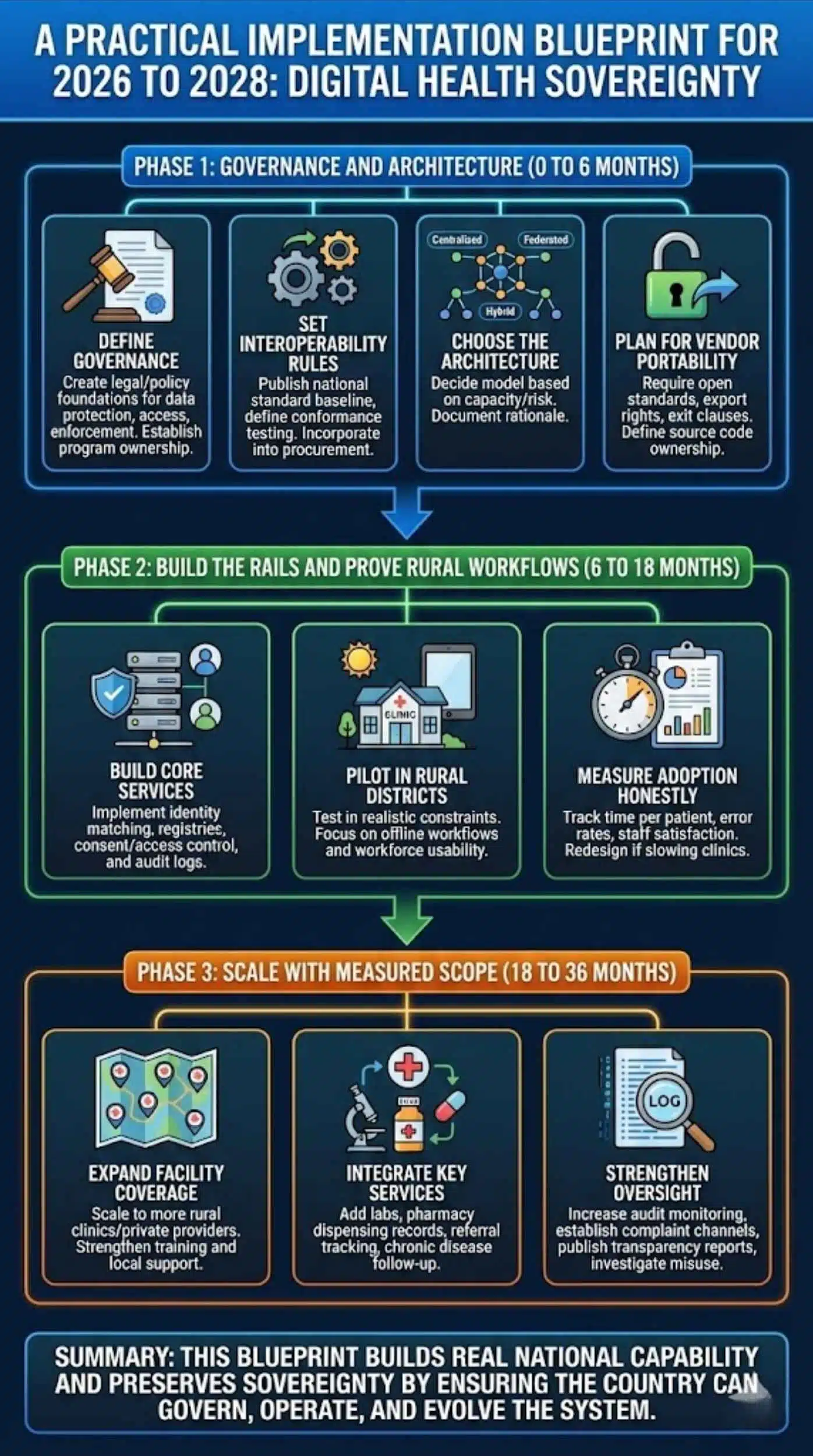

A Practical Implementation Blueprint For 2026 To 2028

The best national programs treat implementation as a multi-year change process, not a software deployment. Here is a phased blueprint that fits rural economies.

Phase 1: Governance And Architecture (0 To 6 Months)

Define governance

Create clear legal and policy foundations for data protection, access rules, and enforcement. Establish who owns the program and how decisions are made.

Set interoperability rules

Publish a national standard baseline, and define conformance testing. Make standards part of procurement.

Choose the architecture

Decide between centralized, federated, or hybrid models based on local capacity and risk tolerance. Document the rationale, so the public understands the tradeoffs.

Plan for vendor portability

Require open standards, data export rights, and exit clauses. Define who owns source code where applicable.

Phase 2: Build The Rails And Prove Rural Workflows (6 To 18 Months)

Build core services

Implement identity matching, registries, consent and access control, and audit logs.

Pilot in rural districts

Do not pilot only in flagship hospitals. Choose rural districts with realistic constraints. Treat the pilot as a test of offline workflows and workforce usability.

Measure adoption honestly

Track time per patient, error rates, and staff satisfaction. If the system slows down clinics, redesign before scaling.

Phase 3: Scale With Measured Scope (18 To 36 Months)

Expand facility coverage

Scale to more rural clinics and private providers where relevant. Strengthen training and local support.

Integrate key services

Add labs, pharmacy dispensing records, referral tracking, and chronic disease follow-up.

Strengthen oversight

Increase audit monitoring, establish complaint channels, publish transparency reports, and investigate misuse.

This blueprint builds real national capability and preserves sovereignty by ensuring the country can govern, operate, and evolve the system.

Where National Programs Succeed And Where They Fail

In 2026, many countries will claim progress through big numbers. Numbers matter, but quality matters more.

Common success signals include:

- Rural clinics actively using the system, not just registered

- Records that are clinically useful and up to date

- Secure sharing across facilities with patient control

- Fewer duplicates and fewer lost follow-ups

- Clear accountability when misuse occurs

Common failure patterns include:

Fragmentation by design

Multiple agencies build separate systems for separate programs. Each system captures data, but none share it properly.

Over-centralization without safeguards

A large central database becomes a high-value target. Without strong access controls and audits, the system invites misuse.

Digitizing bureaucracy

Staff spend more time clicking forms than treating patients. The system becomes a reporting tool, not a care tool.

Exclusion through identity gates

If services require perfect identity proof, vulnerable people get blocked. A sovereignty approach should protect citizens, not filter them out.

Vendor lock-in

A country becomes dependent on a vendor’s proprietary stack. Costs rise, flexibility falls, and sovereignty weakens.

A strong program anticipates these risks and builds mitigations into policy, architecture, and operations.

A Rural-First Design Toolkit

To make the article actionable, here are design patterns that consistently improve rural outcomes.

Offline-First Data Capture

Use local storage with secure encryption and sync when connectivity returns. Ensure conflict resolution rules are clear so data stays consistent.

Minimal Essential Dataset

Start with the minimum dataset that supports decisions and continuity. Expand once workflows stabilize.

Assisted Digital Access

Enable patients to access records through trusted agents like community health workers. Use role-based access and clear consent scripts.

Paper-Compatible Outputs

In many rural areas, paper still matters. Provide printable summaries with secure verification codes so patients can carry information safely.

Resilient Identity Matching

Allow multiple identifiers. Support corrections. Reduce false rejections. Prioritize safety in matching decisions.

Training That Fits Reality

Short modules, local language, practical scenarios, and continuous refreshers work better than one-time workshops.

These patterns turn a national vision into a rural reality.

Cybersecurity And Resilience In 2026

Cybersecurity is not a side issue. It is a defining feature of digital health sovereignty.

A sovereign record system should implement:

- Encryption in transit and at rest

- Strong authentication for providers

- Role-based access control

- Continuous monitoring and anomaly detection

- Regular penetration testing

- Secure backup and disaster recovery plans

- Incident response playbooks and breach notification rules

In rural settings, resilience also means operational continuity. A clinic must still function during outages. Offline workflows and fallback procedures are part of security because they prevent dangerous workarounds and data loss.

Trust, Legitimacy, And Public Acceptance

A national record system succeeds only when people trust it. Trust comes from design and governance, not from slogans.

Key trust-building actions include:

Explain the purpose clearly

People support systems when they understand the benefits and limits. A clear public narrative reduces fear.

Make access visible

Patients should be able to see who accessed their data, even if they check through a clinic or hotline.

Offer real recourse

People need a complaint path, correction mechanisms, and consequences for abuse.

Protect sensitive groups

Rural communities may include marginalized populations. Policy should prevent discrimination and misuse.

When a country builds these elements, digital health sovereignty becomes something citizens can feel, not just something officials can say.

Metrics That Define Success

In 2026, the best programs will measure success beyond enrollment.

Here is a balanced metrics set:

Coverage Metrics

- Percentage of rural facilities onboarded

- Percentage of rural patients with usable records

- Percentage of providers actively using the system monthly

Quality Metrics

- Duplicate record rate

- Matching error rate

- Completeness of key fields for priority programs

- Data timeliness for labs and referrals

Use And Impact Metrics

- Referral completion rate

- Follow-up adherence for chronic disease

- Immunization continuity across districts

- Reduced repeat tests due to accessible histories

Equity Metrics

- Adoption by geography, gender, and income group

- Service denial events linked to identity verification

- Patient satisfaction in rural districts

Trust And Security Metrics

- Number of audited access events

- Number of confirmed misuse cases and actions taken

- Time to detect and respond to incidents

Metrics like these protect the program from becoming performative. They keep the focus on outcomes.

The 2026 Thesis For Rural Economies

The 2026 push for national digital health records is not a trend. It is the next stage of health system modernization. Done well, it can reduce rural exclusion, improve continuity of care, and strengthen national preparedness. Done poorly, it can create surveillance fears, vendor dependence, and new forms of inequality.

Digital health sovereignty provides a useful compass. It forces decision-makers to treat health data as critical infrastructure, to govern it with transparency, and to build it in a way that serves the whole country.

For rural economies, the winning strategy is simple to say and hard to execute: design for rural constraints first, protect trust through enforceable governance, and scale through interoperable rails rather than isolated apps. If countries get these choices right in 2026, national digital health records can become one of the most impactful public health investments of the decade.

Final Words

In 2026, national digital health records will only succeed if they’re built with real sovereignty—strong governance, secure data control, and true interoperability. For rural economies, the priority is simple: design for low connectivity, limited staff, and inclusive access from day one. When countries get these fundamentals right, digital health becomes a trust-based system that follows people everywhere and improves care for the communities that need it most.