The hum of sewing machines fills the air. In a cramped factory just outside Dhaka, 27-year-old Reshma begins her 12-hour shift, piecing together fast fashion destined for Western storefronts. A decade ago, she survived the Rana Plaza disaster—a building collapse that killed over 1,100 garment workers. Today, she still earns barely enough to feed her children.

South Asia’s garment workers form the backbone of a multi-billion-dollar global industry. From Bangladesh and India to Pakistan and Sri Lanka, millions of workers—primarily women—produce clothes worn across Europe, North America, and beyond. These workers stitch garments for household brands like Zara, H&M, Levi’s, and Shein. Yet, while profits soar and new fashion lines launch weekly, the people who make our clothes continue to battle low wages, unsafe conditions, and suppressed rights.

This article explores the hard truths behind the clothing tags. It’s a journey through sweatshop economies, hidden supply chains, pandemic fallout, and the fight for fair pay and dignity. Because fashion may change with the seasons—but labor injustice, unfortunately, remains stitched into its seams.

The Backbone of Fast Fashion

South Asia has become the epicenter of fast fashion production. Bangladesh alone exports over $45 billion in ready-made garments (RMG) annually, making it the world’s second-largest exporter after China. India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka also contribute significantly to global supply chains, producing clothing for retail giants such as Zara, H&M, Walmart, Uniqlo, Gap, and Shein.

But behind every price tag lies a different story—one of razor-thin margins, relentless targets, and long hours. A pair of jeans sold for $50 in New York may earn the worker less than 50 cents. This imbalance is the core contradiction of the global fashion industry: huge profits at the top, systemic poverty at the bottom.

In Bangladesh, the average garment worker earns just $115/month, while in Pakistan or India, wages vary widely across states and factories. Most workers can’t afford basic healthcare, nutritious meals, or schooling for their children. They are caught in a cycle of low wages and high expectations—with little power to demand better.

Feminized Labor and Structural Exploitation

Walk into any garment factory in Dhaka, Tiruppur, or Lahore, and you’ll see rows of young women at sewing machines. Women comprise 70–80% of South Asia’s garment workforce, chosen deliberately by employers who view them as more “compliant” and “cost-effective.”

But this gendered workforce structure fuels silent exploitation. Female workers face:

-

Sexual harassment from supervisors

-

Verbal abuse over production quotas

-

Lack of maternity benefits

-

Zero representation in factory-level decisions

Many are migrants from rural villages, with little education and few options. Their labor is essential—but their dignity is dispensable.

A Decade Since Rana Plaza: What’s Changed?

On April 24, 2013, the Rana Plaza building in Dhaka, Bangladesh, collapsed—crushing thousands of workers beneath concrete and steel. 1,134 people lost their lives, and more than 2,500 were injured in what remains one of the deadliest industrial disasters in history.

The tragedy shook the world. For the first time, global consumers were confronted with the real human cost of cheap fashion. In response, major brands, labor organizations, and governments launched a wave of safety-focused reforms.

The most notable initiative was the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, a legally binding agreement signed by over 200 international brands. It led to thousands of factory inspections, structural renovations, and safety trainings. The Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, launched by North American retailers, introduced parallel measures.

These efforts undeniably improved physical safety in export-compliant factories. But what about the thousands of unregistered, subcontracted workshops that fall outside the scope of these agreements?

Safety Standards—On Paper vs. In Practice

While the top-tier factories serving brands like H&M or Levi’s have improved, many workers remain in shadow zones—spaces where legal protections and safety protocols don’t apply. These subcontracted units are often:

-

Cramped and poorly ventilated

-

Without emergency exits

-

Lacking fire extinguishers or safety drills

-

Not registered with labor authorities

Furthermore, factory inspections can be manipulated—with “showrooms” prepared for auditors, while real production happens off-site in unsafe conditions.

According to a 2024 Human Rights Watch report, nearly 40% of workers in Dhaka’s RMG sector still operate in facilities that fail basic safety tests. Similar conditions exist in parts of Lahore, Karachi, and Tiruppur.

The Wage Problem: Surviving, Not Living

For millions of garment workers in South Asia, the paycheck at the end of the month isn’t enough to live—it’s barely enough to survive.

In Bangladesh, the minimum wage for garment workers was raised in 2024 to Tk 12,500/month (~USD $115), following years of pressure from unions and global rights groups. While it may appear like progress, organizations such as the Asia Floor Wage Alliance estimate that a living wage—what a worker actually needs to meet basic needs with dignity—is closer to Tk 23,000–25,000/month (~USD $210–230).

In India, the gap is just as wide. Tamil Nadu’s minimum wage for textile workers is around INR 8,000–10,000/month (~USD $100–120), but the living wage is estimated at INR 18,000–20,000. In Pakistan, similar gaps persist amid rapid inflation and currency devaluation.

The result? Workers take loans to afford rice. They skip meals so their children can eat. They live in cramped, shared housing to save rent, often without access to clean water or electricity.

💬 Worker Testimony:

“I stitch clothes for people who will never know my name. I work all day, but at night I wonder if I can buy cooking oil tomorrow.” — Ayesha, worker in Karachi, Pakistan

Inflation, Currency Devaluation, and Unfair Wage Structures

Even when wages go up on paper, real income is eroded by inflation, especially in essentials like food, rent, and transport. Over the past two years:

-

Bangladesh’s taka has lost nearly 25% of its value against the dollar

-

Food prices in India and Pakistan have surged by 30–40%

-

Transport and housing costs in garment hubs like Dhaka, Tiruppur, and Lahore have doubled

To make matters worse, many factories use piece-rate payment systems, where workers are paid by the number of garments produced—not by the hour. This creates immense pressure to skip breaks, work faster, and stay longer just to meet basic targets.

And those who are paid hourly or monthly are often hired on short-term or verbal contracts, allowing employers to withhold wages or fire them without notice.

The Rise of Hidden Workspaces

While brand-name factories may meet compliance standards, a large portion of garment production in South Asia occurs in informal, subcontracted units—the industry’s hidden underbelly.

These small-scale workshops often operate in residential neighborhoods, basements, or converted homes. They are off the books, outside the reach of regulators, and typically serve as overflow units for larger factories trying to meet tight global deadlines. Here, labor laws don’t apply, inspections never happen, and workers have zero protection.

In these informal spaces, common abuses include:

-

No written contracts

-

Delayed or denied wages

-

Verbal abuse for not meeting quotas

-

Lack of toilets, fire exits, or ventilation

Subcontracting allows top-tier factories and brands to maintain plausible deniability. They claim compliance while pushing production into invisible zones, where safety, ethics, and dignity are optional.

Anti-Union Tactics and Fear Culture

Unionizing in South Asia’s garment sector is not only difficult—it can be dangerous.

In many factories, talking about unions is grounds for dismissal. Employers routinely fire or blacklist workers who attend labor meetings or attempt to form unions. Some go further: hiring thugs to intimidate organizers, filing police complaints, or exploiting workers’ lack of legal literacy.

In Bangladesh, less than 5% of factories have active trade unions, and even fewer in India or Pakistan. Many women fear losing their job—or facing harassment—if they speak up.

Legal barriers add to the problem. In Pakistan, forming a union requires a minimum number of employees and lengthy approval processes. In India, state-level restrictions limit union registration in export zones. Sri Lanka’s unions have shrunk under political and economic instability.

Pandemic Fallout and the Price of Recovery

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, global fashion retailers abruptly canceled billions of dollars’ worth of orders, leaving factories in South Asia with warehouses full of unsold stock and no cash to pay workers.

According to the Worker Rights Consortium, brands canceled over $3 billion in orders from Bangladesh alone in the first months of the pandemic. Factories responded by closing operations or firing workers without compensation.

Thousands of garment workers were:

-

Laid off without notice

-

Denied wages already earned

-

Left without healthcare in the middle of a public health crisis

Many returned to their villages, only to fall deeper into poverty. Others stayed in cities like Dhaka or Tiruppur and worked for half pay, or none at all, hoping the factories would restart.

💬 Worker Quote:

“They told us, ‘The brands have canceled. We have nothing to give you.’ But we gave them everything we had.”

While some brands eventually paid back their dues—thanks to global campaigns like #PayUp—the damage had already been done.

Post-COVID Production Boom Without Protections

As Western economies reopened, demand for fast fashion surged again. Factories in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan ramped up production—but with even fewer protections than before.

Workers were expected to work longer hours to meet backlogs, often without:

-

Hazard pay

-

Protective equipment

-

Sick leave for COVID-related illness

Many factories also avoided rehiring unionized or experienced workers, instead recruiting fresh labor at lower wages. Those who did return found conditions worse: tighter quotas, fewer breaks, and even more surveillance.

Gender-based violence and mental health crises increased, particularly among women juggling unpaid care work at home with dangerous jobs in the factory.

Ethical Sourcing: Greenwashing or Genuine Shift?

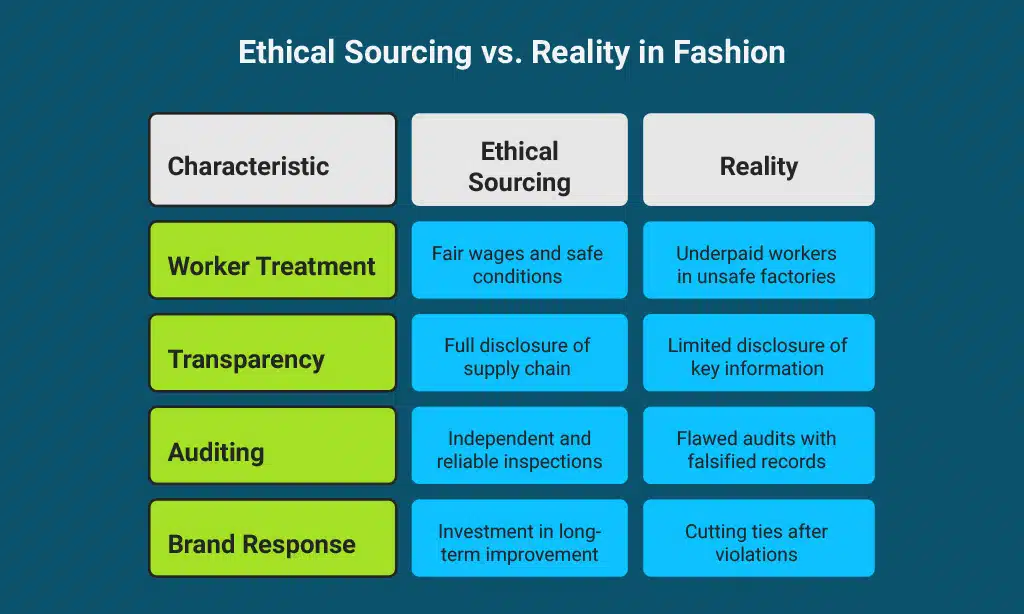

In the wake of disasters like Rana Plaza and the COVID-19 crisis, many global fashion brands ramped up their messaging around “ethical sourcing,” “sustainability,” and “responsible production.” But how much of that is reality—and how much is reputation management?

Brands now tout “conscious collections,” “climate-positive” lines, and “fair trade” labels. Yet, many of these garments are still made by underpaid workers in unsafe or informal factories. The language has changed—but the conditions often haven’t.

One of the biggest issues is transparency. While some brands publish factory lists, they rarely disclose:

-

Subcontractor locations

-

Wage structures

-

Overtime hours

-

Safety violations

Factory audits—often commissioned by the brands themselves—are known to be flawed. In many cases, factories prepare fake records or coach workers before inspectors arrive. And once violations are discovered, brands often respond by cutting ties rather than investing in long-term improvement.

Global Campaigns and Legal Innovations

There is hope—driven by worker-led campaigns and legal shifts that are starting to change how brands operate.

The #PayUp campaign launched in 2020 forced brands to honor $22 billion in canceled orders. In 2023, the Bangladesh Accord was renewed as the International Accord, expanding its reach and strengthening its accountability mechanisms.

In Europe, new due diligence laws require companies to prove they’re not profiting from forced labor or unsafe practices across their supply chains. The U.S. has issued import bans on goods linked to labor exploitation, forcing brands to pay closer attention.

Meanwhile, worker advocacy groups like Clean Clothes Campaign, Asia Floor Wage Alliance, and AFWA’s Tracker Tool are pushing for legally binding agreements that go beyond audits and PR.

Takeaways: Stitching Justice Into Every Seam

More than a decade after Rana Plaza, and years after a pandemic that exposed the fragility of global labor, garment workers in South Asia are still fighting for the basics—a safe factory, a fair wage, a voice at work.

The fashion industry has evolved in style, speed, and slogans. But at its core, it continues to run on underpaid, overworked labor, disproportionately borne by young women who remain unseen by the consumers they serve.

Reforms have come, but unevenly. Some factories are safer, some brands more transparent. Yet millions still toil in silence—out of sight, off the books, and outside the system.