Step into the world of Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay, and the first thing you’ll notice isn’t just the people—it’s the place. You might find yourself in a creaking, three-story ancestral home in Kolkata, where dozens of eccentric relatives live in a state of loving chaos. It’s the places in shirshendu mukhopadhyay s fiction that truly define the experience. For Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay, one of modern Bengali literature’s most beloved storytellers, settings are never just passive backdrops. They are active, breathing characters. They are the engines of the plot and the source of the magic. His unique literary style, often called ‘Adbhut Ras’ (the essence of the wondrous or the absurd), depends entirely on where the story happens.

His fictional map is split into two major territories. First, there are the ‘Railways’—the tangible, nostalgic, and deeply real places of his own childhood. These are the small towns, the railway colonies, and the curious corners of old Kolkata. Second, there are the ‘Reveries’—the fantastical, impossible worlds born from his boundless imagination. These are the underground chambers, the haunted gardens, and the homes of mad scientists.

But the true genius of Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay isn’t in these two separate worlds. It’s in the magical, invisible line where they blur together. It’s in his power to convince you that a ‘Reverie’ is hidden just beneath the floorboards of the ‘Railway’—that if you just look hard enough, you, too, might find a friendly ghost in your attic or a mysterious chamber under your house.

This article explores that map. We will travel from the real-world railway platforms that shaped his youth to the fantastical reveries that defined his fiction, to understand how Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay builds worlds that feel more real than our own.

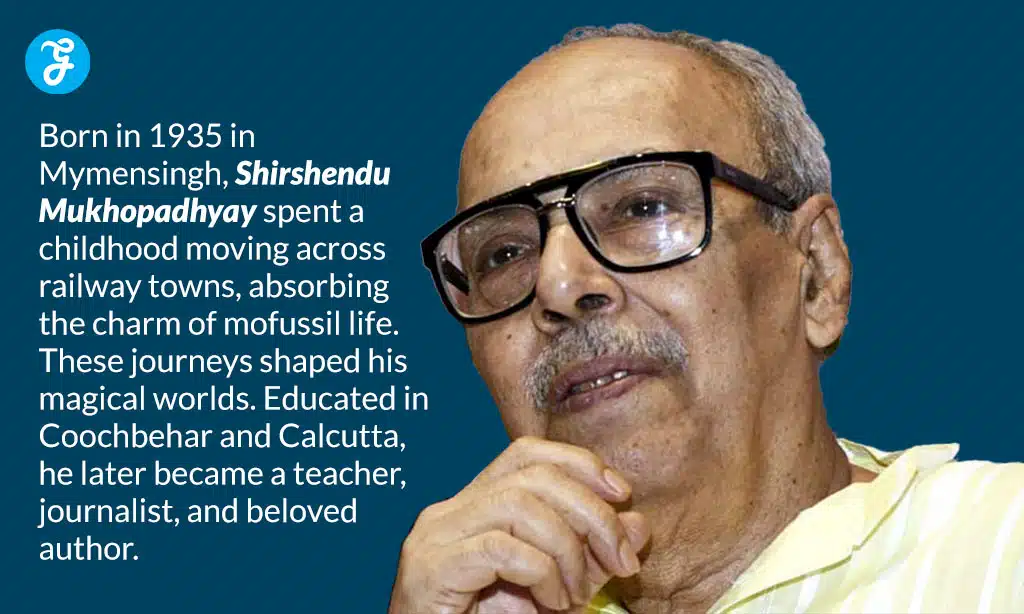

The Man Behind the Magic

To understand the why behind his magical worlds, it helps to know the man himself. Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay was born on November 2, 1935, in Mymensingh, which is now in Bangladesh. His life was set in motion by the very “railways” that feature so prominently in his fiction. His father’s job with the railways meant the family was always on the move.

This nomadic childhood took him across a map of pre- and post-partition India—from Bihar and Assam to numerous small towns in Bengal, such as Coochbehar and Jalpaiguri. He didn’t just see these places; he lived in them, soaking in the unique atmosphere of mofussil towns and railway colonies. This experience became the raw material for his art.

For his formal education, he attended Victoria College in Coochbehar and later earned a Master’s degree in Bengali from the University of Calcutta. He began his professional life as a school teacher, a role that perhaps honed his ability to connect with young minds. His literary journey began in 1959 with his first story “Jal Taranga” and his first novel, Ghunpoka (The Woodworm), published soon after. He later joined the staff of the Anandabazar Patrika newspaper and became a key figure at Desh magazine, becoming a beloved journalist and author, and a household name in Bengali literature.

The ‘Railways’ — Grounded in Nostalgia and Reality

Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay’s father worked for the railways. This single biographical fact is perhaps the most important key to understanding his work. Because of his father’s job, a young Shirshendu spent his childhood moving across a vast, undivided Bengal and beyond. He lived in Mymensingh (now in Bangladesh), Bihar, Assam, and numerous small towns in West Bengal like Coochbehar, Jalpaiguri, and Domohani.

He didn’t grow up in one fixed home. He grew up in the spaces between places. He grew up on trains, in railway quarters, and in the small mofussil towns that revolve around the railway line. This childhood gave him a deep, unshakable nostalgia for a specific kind of atmosphere: the feeling of a place that is slow, eccentric, and full of forgotten stories. These real-world memories became the “Railways” that ground his fiction. They are the most recognizable places in shirshendu mukhopadhyay s fiction.

The Call of the Mofussil: Small Towns and Lost Homes

Long before “small-town life” became a popular genre, Shirshendu was its master. The mofussil (a term for rural, small towns outside the big city) is his signature setting. He writes about these towns not as a tourist, but as someone who knows their every sound and smell.

In his novels, the mofussil is more than just a village. It’s a state of mind.

- It is a place of slow time. Life is not governed by the clock, but by the seasons, the arrival of the 3:15 train, and the evening gossip sessions at the local tea stall.

- It is a haven for eccentrics. Big cities force everyone to be the same. But in Shirshendu’s small towns, every character is allowed to be gloriously, wonderfully weird. You have the local homeopathic doctor who is also an amateur ghost-hunter, the retired zamindar who spends all day flying kites, and the schoolteacher who is secretly trying to invent a time machine.

- It is a world of fading values. His stories often carry a gentle sadness. They are set in a Bengal where old traditions, joint families, and a simple, community-focused life are being replaced by modern “urban” habits. In novels like Chakra, he explores this gentle clash between the old rural world and the new city mindset.

This mofussil setting is his stage. By making the place so familiar and nostalgic, he prepares the reader to accept the strange things that are about to happen there. Because the town feels real, the magic feels possible.

| At-a-Glance: The Mofussil Setting | |

| What it is: | A small, rural, or semi-urban town in Bengal. |

| The Atmosphere: | Nostalgic, slow-paced, misty, and slightly decaying. |

| Key Elements: | The local market, the railway station, the post office, the tea stall, the riverbank. |

| Typical Characters: | Eccentric doctors, retired old men, curious children, local gossips. |

| Function in Story: | It acts as a “control group”—a baseline of reality against which the adbhut (wondrous) events can be contrasted. |

Kolkata: The City of Curious Corners and Old Houses

When Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay writes about Kolkata, he is almost never writing about the Victoria Memorial or the Howrah Bridge. His Kolkata is not the city of landmarks. It is the city of bylanes, of peeling paint, of forgotten attics, and, most importantly, of the bonedi bari—the sprawling, crumbling ancestral home.

His most famous children’s novel, Manojder Adbhut Bari (Manoj’s Wondrous House), is the ultimate example. The “house” in the title is not just a setting; it is the main character. It’s a massive, labyrinthine building in North Kolkata, packed with a joint family of more than fifty people.

This house is a perfect symbol of his “grounded” settings:

- It’s a Labyrinth: The house has countless rooms, secret passages, dark corridors, and a rooftop that is a world unto itself. The children in the story are constantly exploring it, finding new mysteries within its walls. The house is a physical map of a complex family.

- It’s a Microcosm: The house is its own self-contained world. It holds feuding brothers, loving aunts, a quirky grandfather, and even a bumbling local dacoit. The house protects and contains all this chaos, just as the story contains its own adbhut elements.

- It’s a Portal: The house seems perfectly normal to the family, but it is a magnet for the strange. A lost dacoit, a secret agent, and a mystery all converge on this “normal” house. The house acts as a bridge, a real place where the reverie can come crashing in.

He uses this template again and again. His adult novels are full of characters living in old, rented rooms (mess-bari) or decaying family homes. These places are soaked in history and memory. They have a “ghost” of their own, even before he adds a real one. This tangible, textured, and slightly broken-down Kolkata is the perfect, solid ground from which his most fantastic ideas can take flight.

| At-a-Glance: The Kolkata Setting | |

| What it is: | Not the modern city, but the old, decaying parts of North and Central Kolkata. |

| The Atmosphere: | Crowded, chaotic, intimate, and full of history. |

| Key Elements: | The bonedi bari (ancestral home), the mess-bari (boarding house), rooftops, narrow lanes, attics (chilekotha). |

| Key Example: | Manojder Adbhut Bari (Manoj’s Wondrous House). |

| Function in Story: | The house acts as a maze, a character, and a container for the eccentricities of a large joint family. |

The Railway Motif: Journeys to the Known and Unknown

The railway is the artery that connects all of Shirshendu’s real-world settings. It links the mofussil to Kolkata. It is the thread of his own childhood. And in his fiction, it is a powerful, recurring symbol.

In a Shirshendu story, a railway station or a train compartment is a liminal space. It is a place that is neither here nor there. It is a place of transition, of waiting, and of possibility. When a character is on a train, they are literally suspended between their old life and a new one.

- A Place of Escape: Characters often take a train to escape a boring job, a bad situation, or the mundane world. The journey itself is a chance for adventure.

- A Place of Mystery: The train is a closed environment where strangers are forced together. A mysterious passenger can enter a compartment and change the protagonist’s life forever.

- A Place of Atmosphere: He is a master of painting the atmosphere of a railway platform. Think of a small-town station at dusk. The single gas lamp, the lonely tea-stall owner, the sound of the approaching train in the distance—it’s an atmosphere thick with mystery and nostalgia.

The story Gandhota Khub Sandehojanok (The Suspicious Odour) is set in the very real-sounding railway town of Domohani. The town is filled with railway quarters and revolves around the train schedule. But this very real, very mundane railway town is also famously inhabited by a group of helpful, invisible ghosts. The “Railway” setting makes the “Reverie” of the ghosts feel completely normal, even funny.

For Shirshendu, the railway is the literal and metaphorical vehicle that carries his characters from the everyday world of “Railways” to the magical world of “Reveries.

| At-a-Glance: The Railway Motif | |

| What it is: | Trains, railway platforms, and railway colonies. |

| The Atmosphere: | Nostalgic, transitional, mysterious, and lonely. |

| Symbolic Meaning: | Escape, journey, fate, the meeting of strangers, the line between worlds. |

| Biographical Link: | His father was a railway employee, and he grew up in these settings. |

| Function in Story: | It’s a “liminal space” where the ordinary rules of life are suspended and anything can happen. |

The ‘Reveries’ — Inventing Fantastical Worlds

If the “Railways” are the solid ground of Shirshendu’s world, the “Reveries” are the strange, colorful skies above it. These are the settings that cannot be found on any map. These inventive places in shirshendu mukhopadhyay s fiction are born purely from his imagination to serve the story.

But why invent a world? Why not just set all his stories in Kolkata or a small town? The answer is simple: his characters.

When your story is about a 200-year-old ghost, a boy who finds magic goggles, or a scientist who invents a machine that can talk to aliens, you can’t just place them in a modern, realistic setting without breaking the story. The place must be special. It must have its own rules that allow for the magical to exist.

This is not “magic realism” as seen in Latin American literature, where the magical is treated as a political statement. This is Adbhut Ras. The goal is not to make a political point, but to create a sense of wonder, absurdity, and profound, often humorous, fun.

In interviews, Shirshendu has said that he often doesn’t plan his plots. He starts with a single line or an image. This process is one of “reverie”—of dreaming onto the page. He builds these fantastical worlds as “sandboxes” where his most absurd and wonderful ideas can live and breathe.

| At-a-Glance: Realism vs. Reverie | |

| Realism (The Railways) | Reverie (The Fantastical) |

| Based on his real childhood. | Born from his imagination. |

| The setting is familiar (Kolkata, a town). | The setting is impossible (an underground world). |

| The rules of physics apply. | The rules of magic and absurdity apply. |

| Houses normal eccentrics. | Houses supernatural characters (ghosts, aliens). |

| Goal: To create nostalgia and grounding. | Goal: To create wonder and possibility. |

Case Study: Gosaibagan and the Geography of Ghosts

Perhaps the most famous of his “reveries” is the setting for his beloved children’s novel, Gosaibaganer Bhoot (The Ghost of Gosaibagan).

The story is about Burun, a boy who is terrible at math and lives in fear of his teacher. He finds a friend in a ghost named Nidhiram. But this ghost can’t just be anywhere. He needs his own place. That place is Gosaibagan.

Gosaibagan (Gonsai’s Garden) is not just any spooky garden. It is a carefully constructed “pocket dimension” that operates on “ghost rules.”

- It has specific landmarks: The garden is defined by its broken walls, its thick, ancient trees, and one special tree (a sheora tree, or ‘streblus asper’) which is the ghost’s traditional home.

- It has its own logic: In the outside world, ghosts are scary. In Gosaibagan, the ghost Nidhiram is a kind, lonely figure who is actually terrified of a local tough guy. The garden is a “safe space” for this absurd, gentle brand of horror.

- It is a place of transformation: The garden is where the human boy Burun goes to escape his very real fears (his math teacher). In this magical place, he finds the courage to face the real world. The “reverie” of the garden gives him the strength to deal with the “railway” of his everyday life.

By creating Gosaibagan, Shirshendu gives his ghost a home, a personality, and a set of rules. He invents a geography for the supernatural. The garden is a place where the barrier between the living and the dead is thin, friendly, and very, very funny.

| At-a-Glance: Deconstructing Gosaibagan | |

| The Novel: | Gosaibaganer Bhoot (The Ghost of Gosaibagan) |

| The Setting: | A forgotten, overgrown, and supposedly haunted garden. |

| Key Inhabitants: | The boy Burun and the ghost Nidhiram. |

| The ‘Adbhut’ Logic: | The ghost is not scary; he is friendly, helpful, and has his own problems. |

| Function in Story: | It’s a “pocket dimension” or “safe space” where the rules of the normal world are inverted, allowing a human and a ghost to become friends. |

Patalghar: The Underground World as a State of Mind

If Gosaibagan is a horizontal reverie (a garden you walk into), then Patalghar (The Underground Chamber) is a vertical one (a world you fall into).

This novel is a brilliant example of a setting that is both a physical place and a powerful psychological metaphor. On the surface, the story is a thrilling adventure. A boy, Subin, finds out that 400-year-old treasure is hidden in a secret underground chamber beneath his ancestral home in a mofussil town.

The Patalghar itself is the “reverie.” It is the fantasy of every child: that a secret world of adventure is hidden just beneath their feet.

- A Metaphor for History: The chamber is literally the “subconscious” of the house. It holds the buried secrets, the forgotten history, and the ancestral treasure of the family. To go down into it is to go back in time.

- A Test of Courage: The “underground” is a classic mythological setting. It’s the dark place where heroes must go to prove their worth. For Subin, descending into the Patalghar is his test of courage.

- The Adventure Beneath the Mundane: This is Shirshendu’s core theme. The house above ground is the “Railway”—a normal, everyday small-town house. But beneath it lies the “Reverie.” The story tells us that the most boring, normal-looking places are often sitting right on top of the most incredible secrets.

The Patalghar is not a real place. It is a dream of history, mystery, and adventure. Shirshendu invents this space to show that the greatest wonders are not far away; they are right under the surface of the mundane, just waiting to be discovered.

| At-a-Glance: The Meaning of Patalghar | |

| The Novel: | Patalghar (The Underground Chamber) |

| The Setting: | A secret, ancient, booby-trapped chamber hidden beneath a normal ancestral home. |

| Symbolic Meaning: | The subconscious, buried family history, hidden treasure, a secret world. |

| The ‘Adbhut’ Logic: | A normal house can contain a 400-year-old mystery. The past is not dead; it’s just underground. |

| Function in Story: | It is the engine of the adventure plot. It’s the physical manifestation of the story’s central mystery. |

The Intersection — Where Railways and Reveries Meet

We have seen Shirshendu’s two worlds: the real “Railways” of his nostalgic past and the fantastic “Reveries” of his imagination. But the final, most important step is to see how he weaves them together.

The true magic of Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay is not in the fantasy alone. It’s in the intersection. It’s in the moments when the ‘Reverie’ world and the ‘Railway’ world collide, and the characters treat this collision as completely normal.

In academic terms, this is called “epistemic continuity.” In simple terms, it means in Shirshendu’s world, a ghost and a postman can exist in the same story, and no one’s head explodes. The characters just accept it. The supernatural, the scientific, and the mundane all share the same universe without any conflict.

Think back to the story Gandhota Khub Sandehojanok, set in the very real railway town of Domohani. The town is filled with normal people working for the railway. It is also filled with ghosts. And what do the ghosts do? They perform invisible labor. They help the humans, they play pranks, they even help the local football team win a match.

This is the intersection:

- The ‘Railway’ (The Real): The town of Domohani, the railway quarters, the local football match.

- The ‘Reverie’ (The Fantastic): The invisible ghosts who live alongside the humans.

- The Intersection (The ‘Adbhut’): The ghosts playing in the football match and helping the humans win.

The genius is in the normalization. The humans know about the ghosts, and they’ve just learned to live with them. The story isn’t about “Oh my god, a ghost!” It’s about “Oh, the ghosts are being mischievous again.”

This is his unique gift. He grounds his most fantastic ideas in the most mundane, realistic, and nostalgic settings. He’ll place a mad scientist in a rusty, rented shed. He’ll have an alien land in a sleepy village. He’ll have a ghost sitting in a railway compartment.

By doing this, he makes the fantasy believable. But more importantly, he makes our own reality magical. He whispers to the reader that our world, the “Railway” of our everyday lives, is also built on top of a “Reverie.” Our own attics might have a secret. Our own local garden might have a friendly ghost. The next train we take might have a passenger who will change our lives.

| At-a-Glance: The Blending Technique | |

| The ‘Railway’ (Grounding) | The ‘Reverie’ (The Magic) |

| A real Kolkata house. | A family dacoit. |

| A real railway town. | Helpful, invisible ghosts. |

| A small-town boy’s fear. | A friendly ghost. |

| A normal ancestral home. | A hidden treasure chamber. |

Awards and Recognition: A Career of Acclaim

A writer with such a unique voice—one that speaks to both children and adults with equal mastery—does not go unnoticed. Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay’s ability to blend the deeply human with the delightfully absurd has earned him some of India’s highest literary honors.

Here is a summary of his major awards:

| Award / Honor | Year(s) | Significance |

| Ananda Puraskar | 1973 & 1990 | A high honor in Bengali literature. |

| Vidyasagar Award | 1985 | For his outstanding contributions to children’s literature. |

| Sahitya Akademi Award | 1989 | For his novel Manabjamin. |

| Banga Bibhushan | 2012 | One of the highest civilian honors from the Government of West Bengal. |

| Sahitya Akademi Fellowship | 2021 | The highest honor from India’s National Academy of Letters. |

| Kuvempu Rashtriya Puraskar | 2023 | A national award for contribution to any Indian language. |

The Enduring Legacy of the Places in Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay s Fiction

To read Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay is to be given a new pair of eyes. He takes the world we know—the boring train ride, the old house, the quiet town—and he tilts it just slightly, showing us the magic hiding in plain sight. His settings are his greatest character. They are born from the ‘Railways’ of his own past, steeped in a powerful nostalgia for a Bengal that is both real and remembered. And they are launched into the sky by the ‘Reveries’ of his limitless imagination, creating impossible, wonderful places that feel like home.

His genius lies in his refusal to separate the two. In Shirshendu’s Adbhut Bengal, the magical is mundane, and the mundane is magical. His legacy is not just a collection of stories, but an entire, wonderfully strange map. He teaches us that the world is far more interesting than we think. He proves that the most fantastic adventures don’t happen in a faraway land, but in the house next door, on the local train, or right beneath our very feet. The places in shirshendu mukhopadhyay s fiction, in the end, are not just locations. They are a reflection of a mindset—one of endless curiosity, profound humor, and the unshakeable belief that the wondrous is always just around the corner.