If you have ever sat down on a flight and quietly wondered, “How clean is airplane air?”, you are not alone. Many travelers imagine that everyone on board is breathing the same stale, recycled air and that it is almost impossible not to get sick after flying.

At the same time, airlines and engineers claim that cabin air is “hospital-grade” and even cleaner than most offices or restaurants.

So which is true? In this guide, we will break down how airplane air systems really work, what science says about germs and chemical fumes, and what you can do to protect your health when you fly.

How clean is airplane air – what most travelers get wrong

Most people focus only on the idea of “recycled air.” But airplane cabins use a mix of fresh outside air and filtered recirculated air, and the whole volume of air is replaced roughly every 2–3 minutes on modern jets.

To really answer How clean is airplane air, you have to look at:

- How the air is supplied and removed

- How powerful the filters are

- How often does the air change

- What actually causes people to get sick on flights

We’ll walk through all of this step by step, with tables so you can scan the key points quickly.

What Exactly Is Airplane Cabin Air?

Airplane cabin air is not just passengers’ breath swirling around forever. It is a carefully managed combination of fresh outside air and filtered recirculated air. Understanding this mix helps answer the question many people have: How clean is airplane air on a typical commercial jet?

Fresh vs Recirculated Air – What’s in the Mix?

Modern jetliners take air from outside, compress it, condition it, and mix it with recirculated cabin air.

Most large commercial aircraft:

- Use about 40–60% fresh outside air

- Mix it with 40–60% recirculated air

- Pass the recirculated portion through HEPA filters before it comes back into the cabin

This process runs continually during the flight. The air you breathe is always being refreshed.

Cabin air mix at a glance

| Item | Typical Situation on Modern Jets | Why It Matters |

| Fresh outside air | ~40–60% of total supply | Constantly dilutes exhaled breath |

| Recirculated cabin air | ~40–60%, filtered | Saves energy, but is cleaned first |

| Filter type | HEPA or HEPA-equivalent on most large jets | Removes tiny particles and droplets |

| Airflow pattern | From ceiling to floor in short sections | Limits front-to-back mixing |

Outside air at cruising altitude is extremely cold and dry. It is compressed (heating it), cooled again, and then mixed into the cabin system, which also kills many microbes because of extreme temperatures and pressure changes.

Cabin Pressure, Humidity, and Comfort

Cabin air feels different from room air because of pressure and humidity. Modern jets keep cabin pressure equal to about 6,000–8,000 feet (1,800–2,400 m) above sea level.

- Oxygen is slightly lower than at ground level, but still safe for healthy people.

- Many passengers feel more tired or get mild headaches, especially on long flights.

Humidity is low. Studies show cabin relative humidity often drops to around 10–20% on longer flights.

- This leads to dry eyes, nose, and throat.

- It can make you feel like you’re getting sick, even when the air itself is clean.

Cabin environment vs home

| Factor | Typical Jet Cabin | Typical Home / Office | Experience for You |

| Pressure | 6,000–8,000 ft equivalent | Near sea level | Mild fatigue, possible headache |

| Humidity | ~10–20% on long flights | 30–50% (often) | Dry eyes, nose, and skin |

| Oxygen level | Slightly lower than at sea level | Normal | Mostly fine for healthy adults |

| Temperature | Controlled by the crew, it can vary by seat | Controlled by building | Some seats feel cold or warm |

People with heart or lung disease can be more sensitive to these conditions. Travel health guidelines like the CDC Yellow Book advise them to talk to a doctor before long flights and ask about supplemental oxygen if needed.

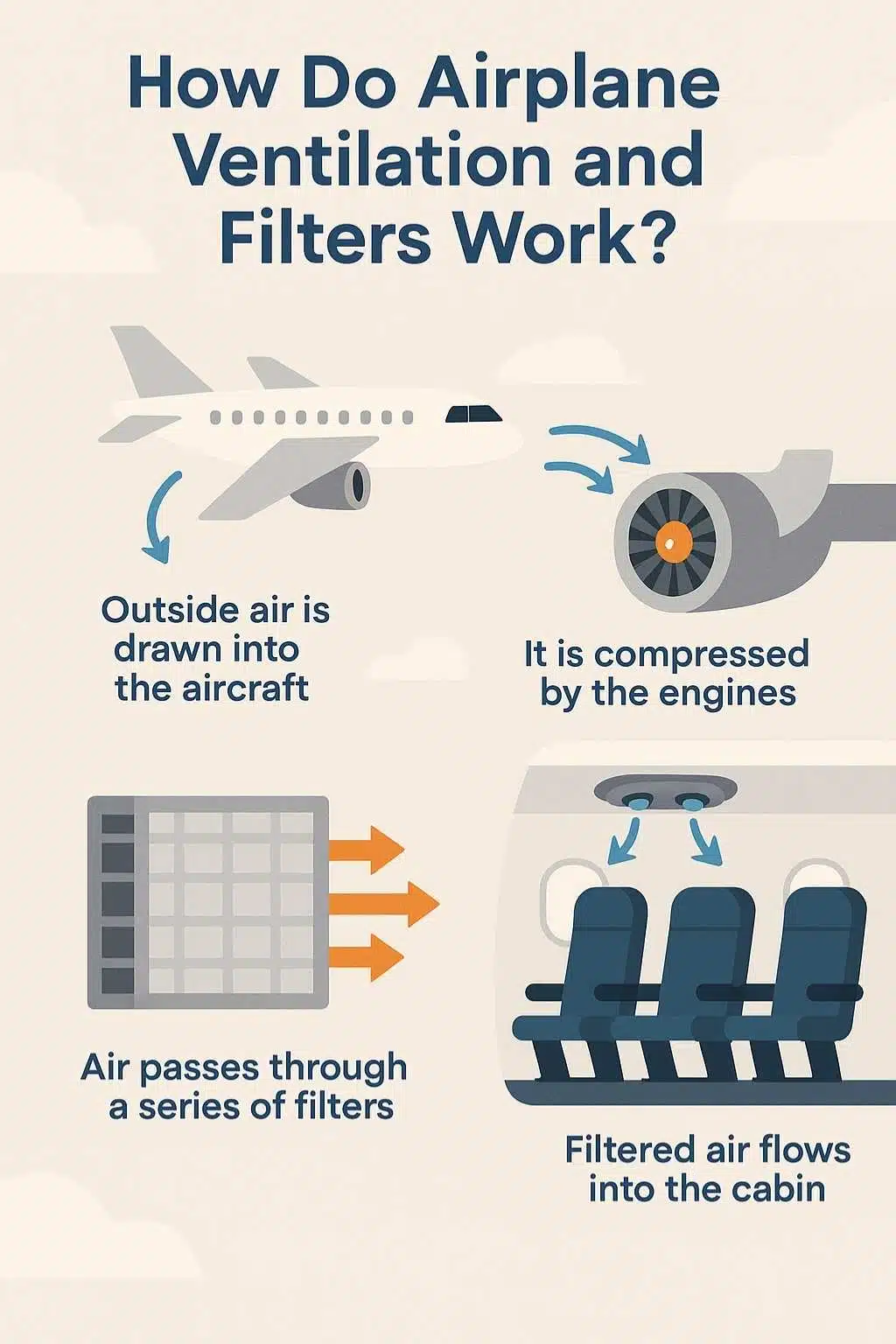

How Do Airplane Ventilation and Filters Work?

Two features keep airplane air relatively clean:

- Very fast air exchange

- High-efficiency particle filters (HEPA)

These are central to understanding how clean airplane air is in real-world conditions.

Air Exchange Rates – How Often Is Air Replaced?

The air change rate shows how many times the air in a space is replaced in an hour.

- IATA and engineering groups report 20–30 air changes per hour (ACH) in a typical large jet cabin.

- That means the entire cabin’s air volume is refreshed about every 2–3 minutes.

- The CDC suggests 5+ ACH as a good target for reducing viral particles in indoor spaces like classrooms or offices.

So aircraft greatly exceed many building targets.

Air changes per hour (ACH)

| Setting / Guideline | Typical ACH or Target | Comment |

| Commercial jet cabin | 20–30 ACH | Air is replaced every 2–3 minutes |

| CDC clean air goal (general) | ≥5 ACH | Helps reduce virus levels indoors |

| Typical office building | Often 2–5 ACH | Lower than planes |

| Poorly ventilated room | <2 ACH | Higher risk for airborne disease |

Air also moves in a top-to-bottom pattern within small cabin sections (usually a few rows). Air is pulled down and out near the floor, rather than flowing from one end of the plane to the other. This design helps prevent long-range mixing of air from the front and back of the cabin.

HEPA Filters – What They Remove and What They Don’t

HEPA filters are another major reason airplane air is cleaner than most people assume.

- Many aircraft cabin filters are HEPA or HEPA-equivalent.

- HEPA filters capture 99.97% of particles with a diameter of 0.3 microns under standard test conditions.

- This includes dust, pollen, bacteria, and many virus-carrying droplets and aerosols.

Viruses such as influenza or SARS-CoV-2 typically travel inside droplets and aerosols that are larger than single viruses, and these particles are easier for HEPA filters to trap.

HEPA filter performance overview

| Feature | Details on Aircraft HEPA Systems | Why It Matters |

| Rated efficiency | ~99.97% at 0.3 microns | Captures most respiratory droplets |

| Target particles | Dust, smoke, bacteria, and many virus-laden aerosols | Reduces infectious particle concentration |

| Used in other spaces | Hospitals, labs, clean rooms | Shows a high standard of cleanliness |

| Filtered air share | Recirculated portion only | Fresh outside air is separate |

HEPA filters do not remove all gases or chemicals. For that, some systems also use carbon or other special media. But for germs in droplets, HEPA is very effective and a key part of the answer to How clean is airplane air from a microbiological perspective.

Is Airplane Air Cleaner or Dirtier Than Other Indoor Spaces?

Now to the big comparison: planes vs buildings vs other transport.

Planes vs Offices, Trains, and Restaurants

If you compare ventilation speed and particle filtration, planes often look better than many indoor spaces.

- Planes: 20–30 ACH + HEPA.

- Offices: often 2–5 ACH, with filters that may be less efficient.

- Restaurants and bars: ACH varies a lot; many are below 5 ACH, especially in older buildings.

Planes vs other indoor environments

| Environment | Typical Ventilation & Filtration | Relative Air Quality (general) |

| Airplane cabin | Very high ACH, HEPA filtration | Often cleaner than many indoor spaces |

| Office | Moderate ACH, filters vary | Can be good or mediocre |

| Restaurant/bar | ACH is often unknown, may be low | Often higher risk when crowded |

| Train/bus | Ventilation and filters vary by system | Depends on the operator and the crowding |

A 2024 CDC air-travel guideline notes that cabin airflow and filtration reduce the spread of many infectious agents compared with typical building environments, as long as systems work correctly.

When people ask How clean is airplane air, they usually compare it to what they breathe at home, in offices, or in shops. In many of those comparisons, airplanes come out surprisingly well.

Regulatory Standards and Airline Responsibilities

Aircraft do not just “wing it” on air quality.

There are rules and standards:

- The FAA manages cabin air quality standards for U.S.-registered aircraft and funds research on bleed air and contaminants.

- EASA and other regulators play similar roles in Europe and globally.

- IATA has issued a Cabin Air Quality briefing and health safety checklists that airlines use during audits.

Airlines are responsible for:

- Maintaining filters and ventilation systems

- Following service schedules for air handling units

- Responding quickly to odor or smoke reports from crew and passengers

Who sets or influences cabin air standards?

| Actor | Role in Airplane Air Quality | Examples |

| FAA | Safety regulations, research funding | Cabin air quality reports, bleed air studies |

| EASA | European aircraft standards | Guidance on cabin environment |

| IATA | Industry guidance and checklists | Cabin air quality briefing paper |

| Airlines | Day-to-day maintenance and operations | Filter changes, system inspections |

If Air Is So Filtered, Why Do People Still Get Sick?

So if the system is strong, why do people still get sick after flights?

Proximity Matters More Than the Air System

The main answer: distance and time near an infectious person.

A 2023 comparative analysis of in-flight outbreaks for SARS-CoV-2, influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, and SARS-CoV-1 found.

- Most secondary cases occur within two rows of the index passenger.

- Risk drops sharply beyond that short range.

A 2024 scoping review of 521 flights reported:

- Secondary attack rates between 0% and 16%, depending on factors such as mask policies, seat layout, and tracing quality.

- Many flights with an infectious passenger had zero onward cases, which supports the idea that planes are not “automatic superspreader boxes.”

Seat distance and risk

| Seat Position vs Index Case | Typical Risk Pattern in Studies |

| Same row or 1 row away | Highest risk of transmission |

| Within 2 rows | Clearly increased risk |

| More than 2 rows away | Much lower risk (not zero) |

| Different cabin section | Rarely involved in documented clusters |

So, you usually do not get sick from “airplane air in general.” You get sick because you spent hours within a couple of seats of someone contagious.

High-Risk Moments Outside the Ideal Ventilation Mode

Not every part of the journey has the same good ventilation as cruise altitude.

Risk can rise when:

- The aircraft is on the ground, before the engines and full systems run.

- People stand in crowded aisles during boarding or deplaning.

- Passengers pack into jet bridges or gate areas with poor airflow.

Surfaces also matter. Viruses like influenza and some bacteria can survive for a while on tray tables, armrests, seatbelts, and lavatory handles. Touching these and then your face can spread disease, although airborne transmission is now seen as more important for many respiratory viruses.

Journey segments and risk factors

| Segment | Ventilation / Behavior Issue | Main Risks |

| Security, check-in | Crowding, mixed ventilation quality | Close contact, long lines |

| Boarding gate | Many people in one area, often with poor airflow | Crowding, talking in close range |

| Jet bridge | Narrow enclosed space | Crowding, limited fresh air |

| Boarding/deplaning | Systems are not always at full power, packed aisles | Close face-to-face exposure |

| In-flight lavatory use | High-touch surfaces | Contact transmission (hand to face) |

Fume Events and Chemical Contaminants

Beyond germs, there is another concern: cabin fumes and bleed air contamination.

Most jets use bleed air, meaning they take compressed air from the engine stages and route it to the cabin after cooling and conditioning. If seals leak, small amounts of engine oil or hydraulic fluid can enter the air stream.

The FAA has led a multi-year study on bleed air contaminants, including:

- Measuring levels of possible contaminants such as VOCs and organophosphates

- Testing sensors that could detect fume events in real time

- Assessing potential health risks from exposure

A 2015 analysis cited by more recent legal reviews estimated 2.7 to 33 fume events per million departures—rare, but not zero.

In 2025, news reports described Delta Air Lines replacing auxiliary power units (APUs) on more than 300 Airbus A320 family jets after fume concerns linked to leaking units.

Fume events in context

| Aspect | What Current Data Suggests |

| Frequency | An estimated 2.7–33 events per million departures |

| Typical triggers | Oil or fluid leaks in bleed air or APU systems |

| Symptoms reported | Headache, irritation, sometimes dizziness |

| Current response | Reporting, investigations, tech upgrades |

These events are not the norm, but they show why regulators and airlines are still working hard to improve detection and prevention.

Beyond Infection: Other Health Effects of Airplane Air

Even if you do not catch a virus or experience fumes, you can still feel bad after a flight. This usually comes from dryness, pressure, and long sitting.

Dehydration, Fatigue, and Jet Lag

Because humidity is so low, water evaporates faster from your eyes, skin, and airways.

Common effects:

- Dry, itchy eyes

- Scratchy throat

- Cracked lips

- Feeling very tired after a long flight

These symptoms are often blamed on “dirty air,” but actually come from dry air and fatigue.

Non-infectious symptoms and simple fixes

| Symptom | Likely Cause in Cabin | Easy Steps to Reduce It |

| Dry eyes | Low humidity | Use lubricating eye drops |

| Dry throat/nose | Dry air, mouth breathing | Drink water often, and avoid too much alcohol |

| Headache | Dehydration, pressure change, noise | Hydrate, rest, consider mild pain relief |

| Tiredness | Time zone shift, prolonged sitting | Move, stretch, plan sleep around the new time |

Respiratory and Heart Conditions

For most healthy travelers, cabin air conditions are safe. But people with certain health problems should be careful.

According to travel health guidance like the CDC Yellow Book:

- People with severe COPD or advanced lung disease may not tolerate lower oxygen well.

- Those with serious heart disease may be at risk from reduced oxygen and the stress of travel.

- Some may need in-flight oxygen and must arrange it with the airline ahead of time.

Who should ask a doctor before flying?

| Condition | Why Cabin Air Can Be a Problem | Typical Advice |

| Severe lung disease | Lower oxygen can cause breathlessness | Pre-flight assessment, oxygen plan |

| Heart failure / severe CAD | Added stress from altitude equivalent | Doctor’s clearance, careful planning |

| Recent major surgery | Clot risk, strain on healing tissues | Follow the surgeon’s specific instructions |

| Serious anemia | Lower oxygen-carrying capacity | Medical check before long flights |

What Does the Latest Research Say About Disease on Planes?

Now let’s look more closely at recent scientific evidence on airborne disease in aircraft.

Evidence from SARS, Influenza, and COVID-19

A 2023 comparative study in Epidemiology & Infection examined documented outbreaks of:

- SARS-CoV-2

- Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09

- SARS-CoV-1

It found that:

- The highest risk was for passengers within two rows of the index case.

- The average infection risk was several times higher within that two-row zone compared with the rest of the cabin.

A 2024 scoping review of 521 flights reported:

- Secondary attack rates between 0% and 16%, depending on factors such as mask policies, seat layout, and case detection.

- Many flights with an infectious passenger had zero onward cases, which supports the idea that planes are not automatically high-risk environments.

Summary of key research findings

| Study Type | Main Conclusion |

| Outbreak investigations | Clusters usually stay within 2 rows of the index case |

| Comparative virus analysis | Similar short-range pattern across SARS/flu |

| Scoping review (521 flights) | SAR varied widely (0–16%), with many zero-spread flights |

| Risk factors identified | Seat distance, mask use, flight length, behavior |

What the Numbers Say About Risk

The 2022–2023 systematic review on aircraft-acquired COVID-19 risk emphasized:

- Longer flights increase total exposure time.

- Lack of masks and crowded boarding increase the chance of spread.

- Good ventilation and HEPA help, but do not fully offset close contact.

Factors that raise or lower risk

| Factor | Effect on Risk During Flight |

| Flight duration (hours) | Longer flight → higher potential exposure |

| Seat distance from the sick person | Closer seats → higher risk |

| Mask wearing | Reduces both emission and inhalation of aerosols |

| Vaccination/immunity | Reduces risk of severe illness |

| Ventilation / HEPA | Lowers overall background virus levels |

What Models Show About Airflow

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models help scientists visualize how exhaled aerosols move in a cabin.

Key takeaways from such models and engineering studies:

- Vertical airflow from ceiling to floor dilutes aerosols fast near vents.

- A person sitting directly next to you is still the main source of your exposure.

- Masks reduce the distance and concentration of exhaled plumes.

Together, real-world data and models give a clearer evidence-based answer to the question How clean is airplane air in terms of infection risk: The air system is strong, but close contact still matters a lot.

How to Protect Yourself: Practical Tips for Cleaner Air and Lower Risk

The good news: you can cut your personal risk with simple, realistic steps.

Smart Seat and Behavior Choices

Seat selection and behavior matter more than most people realize.

- A window seat reduces foot traffic around you.

- Use the overhead air vent (gaspers). Aim it slightly in front of your face, not directly at your eyes. This helps move exhaled air away from your breathing zone.

- Limit unnecessary walking around the cabin.

Practical behavior tips

| Tip | Benefit |

| Choose a window instead of an aisle | Fewer people passing close to your face |

| Use the overhead air vent | Encourages local air mixing away from your nose |

| Stay seated when possible | Fewer close encounters in aisles and galley |

| Face forward, not sideways | Reduces direct face-to-face exposure |

Masks, Hygiene, and Personal Devices

Even when masks are no longer required, you can still choose to wear one:

- A good respirator-style mask (N95-type or equivalent) reduces inhalation of aerosols and helps protect others if you are sick.

- Hand hygiene is still important. Clean hands before eating and after using the lavatory or touching many surfaces.

Personal health kit checklist

| Item | How It Helps on a Plane |

| High-quality mask | Extra protection in crowded conditions |

| Hand sanitizer | Quick cleaning after high-touch surfaces |

| Disinfectant wipes | Wipe the tray table, armrest, and buckle if you want |

| Eye drops | Relieves dryness from low humidity |

| Lip balm & lotion | Reduces discomfort from dry air |

Portable personal air purifiers usually add little benefit in a jet with strong HEPA systems and may not be allowed or useful in tight spaces.

If You Are High-Risk or Immunocompromised

If you are older, immunocompromised, or living with a serious chronic disease, you can still fly, but plan carefully.

- Choose off-peak flights that are less crowded when possible.

- Prefer non-stop routes to reduce time in airports.

- Wear a mask during boarding, deplaning, and busy terminal periods.

- Ask your doctor about vaccines (flu, COVID-19, etc.) and any extra medication to carry.

Extra steps for high-risk passengers

| Step | Why It Helps |

| Travel during quiet times | Less crowding, fewer close contacts |

| Non-stop flights | Less time in queues and connection hubs |

| Consistent mask use | Extra barrier in crowded, noisy areas |

| Doctor’s advice | Tailored plan for your health status |

Myths vs Facts About Airplane Air

Let’s tackle the biggest myths with simple facts.

Common Myths About Airplane Air

| Myth | Fact |

| “Airplane air is just everyone’s breath recirculated.” | A large share of the air is fresh from outside, and recirculated air is HEPA-filtered. |

| “If one person is sick, the whole plane gets sick.” | In real outbreaks, most new cases are within two rows of the index case, not the whole cabin. |

| “Cabin air is dirtier than office air.” | Plane cabins often have higher ACH and better filtration than many buildings. |

| “Fume events show airplanes are toxic all the time.” | Fume events are rare (estimated 2.7–33 per million departures) and are under active study and control. |

The Future of Airplane Air

Cabin air is already tightly controlled, but technology and rules keep evolving.

Technology Upgrades

Current and future improvements include:

- Advanced sensors to detect bleed air contaminants in real time; the FAA’s 2024 cabin air quality report describes testing sensor technologies and ways to reduce diversions from smoke or odor events.

- More efficient HEPA and carbon filters to capture both particles and some chemical vapors.

- Experiments with UV-C and other germicidal systems inside air circulation components.

| Technology | Goal |

| Real-time contaminant sensors | Detect fume events quickly |

| Improved HEPA + carbon media | Capture particles and more VOCs |

| UV-C / disinfection systems | Kill germs inside air ducts |

Design and Operational Changes

Architecture and operations will also shape the future of cabin air:

- New cabin layouts and airflow schemes are being explored to reduce cross-passenger exposure.

- Airlines and engine makers are working on APU and bleed air design fixes after recent fume concerns, like the Delta A320 APU replacement program reported in 2025.

- Post-pandemic cleaning protocols and awareness are likely to stay stricter than before 2020.

Future trends in policy and design

| Area | Expected Direction |

| Regulation | More focus on fume detection and reporting |

| Engineering | Better bleed air seals & alternative systems |

| Operations | Stronger cleaning and air quality monitoring |

Bottom Line – So, How Clean Is Airplane Air, Really?

Let’s answer the question clearly: How clean is airplane air?

In terms of particles and ventilation, airplane cabins are usually very clean:

- Air is refreshed 20–30 times per hour.

- Recirculated air passes through HEPA filters similar to those used in hospitals.

- In many cases, cabin air is cleaner than the air in offices, restaurants, and public buildings, which often fall below 5 ACH and use lower-grade filters.

However, the answer to How clean is airplane air also has another side:

- The main infection risk comes from sitting close to a contagious person, especially within two rows, for several hours.

- Rare fume events remain a concern and are under active study by regulators, airlines, and engine makers.

- Low humidity and cabin pressure can make you feel unwell, even when the air is technically very clean.

So, when you next ask this question, remember: the air system itself is strong and usually cleaner than you think. The real challenge is that many people share a small space for many hours. By understanding how the system works and taking a few simple steps, you can make flying both safer and more comfortable for yourself.

FAQs About Airplane Air Quality

1. Can you really get sick from airplane air?

Not usually. The air is filtered and refreshed often, so the bigger risk is being seated close to someone who is contagious rather than breathing the shared cabin air.

2. Do HEPA filters on airplanes remove viruses?

Yes. HEPA filters capture about 99.97% of airborne particles, including many virus-carrying droplets, making recirculated air very clean.

3. Why does my nose or throat feel dry on flights?

Cabins have extremely low humidity, often below 20%. This dryness irritates your nose, throat, and eyes, but it does not mean the air is dirty.

4. Does opening the overhead air vent help?

It can. The vent increases local airflow around your seat, which may help disperse exhaled particles and improve comfort.

5. Is the air quality worse during boarding?

Yes. Ventilation may not be at full power when the aircraft is on the ground, and crowding in aisles increases exposure risk.

6. Should I wear a mask on a plane?

Optional but helpful. A well-fitted mask reduces the amount of airborne particles you inhale, especially when seated near others.

7. How often is airplane air replaced?

Every 2–3 minutes on most large jets. This rapid turnover helps keep the cabin’s background air remarkably clean.

8. Are older aircraft worse for air quality?

Not always. Many older jets still use HEPA filters and strong airflow systems, though designs and maintenance can vary by airline.