Vallabhbhai Patel is a name that resonates with the weight of a nation’s history, standing tall as the “Iron Man” who stitched together the bleeding fragments of a post-colonial subcontinent into the Republic of India. On this day, December 15, we remember the titan who, in the chaotic dawn of independence, chose the path of difficult unity over easy fragmentation. While Mahatma Gandhi gave the freedom struggle its moral soul, and Jawaharlal Nehru gave it a global voice, it was Sardar Patel who gave India its body—its territorial integrity and its administrative skeleton.

He was not born into a life of politics. He trained for the law, built a reputation through sheer grit, and learned to read people and problems with a courtroom sharpness. That legal mind would later become a national asset—because independent India did not only need passion; it needed structure, negotiation, and enforceable decisions.

Seventy-five years after his death, the silence he left behind in the corridors of power still speaks volumes. When Prime Minister Nehru announced to a hushed Parliament in 1950, “The story of a great life has ended,” he wasn’t just mourning a colleague; he was marking the end of an era of stoic, uncompromising nation-building.

Early years: The Making of a Tough-Minded Realist

To understand the statesman, one must first understand the man. Born in Nadiad, Gujarat, in 1875, Patel was not born into privilege. He was a self-made man who matriculated at the late age of 22, ridiculed by some for his rustic background.

Patel’s early life in Gujarat shaped his political temperament—practical, disciplined, and rooted in the realities of rural India. He understood land, revenue, local power, and the daily anxieties of ordinary families. That understanding later made him effective in mobilizing peasants and negotiating with princes alike.

He saved every rupee to travel to England and study law at the Middle Temple. There, he didn’t just pass; he topped his class, completing a 36-month course in just 30 months. But the true test of his character came not in a classroom, but in a courtroom in Ahmedabad in 1909.

By all accounts, he was ambitious, respected, and headed toward a comfortable life—until India’s freedom struggle demanded a different kind of ambition. What makes Patel’s journey compelling is this: he entered politics as a problem-solver, not as a romantic revolutionary. That problem-solving instinct became his signature.

The Telegram in the Pocket

The anecdote is legendary, yet it bears repeating for what it reveals about his “Iron” nature. Patel was in the middle of a rigorous cross-examination of a key witness in a murder trial. A court attendant handed him a telegram. Patel glanced at it, read the devastating news, and quietly folded the paper into his pocket.

He continued the cross-examination without a tremor in his voice or a break in his concentration. He won the case. Only after the court adjourned did he inform his colleagues: “My wife has died.”

This supernatural ability to compartmentalize personal pain for professional duty became the hallmark of his life. It was this same stoicism that allowed him to navigate the bloody partition of 1947, absorbing the trauma of a fractured nation while methodically working to fix it.

Gandhi’s influence: when a barrister becomes a mass leader

Patel was not initially a fan of Gandhi’s politics. He was a Western-dressed barrister who enjoyed bridge and cynical wit. But a meeting with Gandhi in 1917 changed everything. He burned his foreign suits, donned khadi, and stepped into the dust of rural Gujarat. Patel’s political awakening deepened, and the successful barrister began transforming into a mass leader.

He embraced the discipline of satyagraha, but he brought to it his own distinctly practical temperament. Where Gandhi often spoke in the language of universal ethics, Patel concentrated on organization and outcomes—how to keep a protest non-violent when tensions rise, how to hold farmers together when fear and pressure threaten to break unity, and how to negotiate firmly without surrendering the moral ground of the movement.

This combination of principle and precision is what made him one of the Congress’s strongest organizers: he fused Gandhi’s method of non-violent mass mobilization with a manager’s clarity—planning, accountability, and hard-headed negotiation.

Kheda (1918): organizing courage at the grassroots

In Kheda (1918), Patel helped mobilize farmers who were being pressed to pay land revenue despite severe hardship, and the episode became significant not only for the protest itself but for the leadership model he demonstrated.

He spoke plainly so people understood the cause, insisted on discipline so the movement would not collapse into chaos, protected unity so fear and division couldn’t weaken resolve, negotiated firmly without losing legitimacy, and—most importantly—never allowed the people’s trust to slip away. Kheda revealed a leader who could hold a mass movement together without theatrics, relying instead on clarity, calm authority, and careful organization.

Bardoli (1928): The Moment India Began Calling Him “Sardar”

His leadership in the Bardoli Satyagraha of 1928 is where the legend truly began. The British government had unjustly raised taxes by 22% during a time of famine. Patel organized the farmers with military precision. He set up camps, established an intelligence network to track government officials, and rallied the morale of the peasants with fiery speeches.

“The Government merely makes paper tigers dance and cause fear in you. You shed your fear and once be bold. You will see that Government will seek your advice.”

The British administration tried everything—confiscating land, auctioning cattle, arresting leaders—but the peasants of Bardoli, under Patel’s command, did not break. The government eventually capitulated, scrapping the tax hike. It was the women of Bardoli who, in admiration of his leadership, first bestowed upon him the title “Sardar” (Chief). From that moment on, he was no longer just a lawyer; he was the Commander of the people.

The Congress organizer: building a movement that could govern

India’s freedom struggle was not only about protest—it was also about readiness. Patel understood that if the British left, India would need institutions, systems, and administrative continuity. Inside the Indian National Congress, Patel became known as the leader who could: settle disputes, build consensus, raise resources, select candidates, and keep the organization functioning under pressure.

He presided over the Karachi session (1931), a period when the freedom movement was wrestling with questions about rights, governance, and the shape of independent India. Even when his ideology differed from colleagues, Patel usually prioritized unity of purpose over winning arguments.

And like many leaders of his generation, he paid the price: multiple imprisonments, repeated disruptions to personal life, and years stolen by colonial repression.

1947: Independence arrived with fire, and Patel faced the fire

The story of India’s independence is often told as a celebration. Patel’s story forces us to remember the harder truth: independence also arrived amid fear, displacement, and communal violence. Patel approached this moment with a painful realism. He was not blind to idealism; he simply believed that a country cannot survive on ideals alone when the ground is burning.

As India moved toward independence, Patel held key responsibilities in the transition and then became one of the most powerful members of the new government. In that role, he faced several urgent crises at once: refugee flows, riots and revenge violence, administrative breakdown, and the looming question of the princely states.

The Magnum Opus: Unifying 562 Princely States

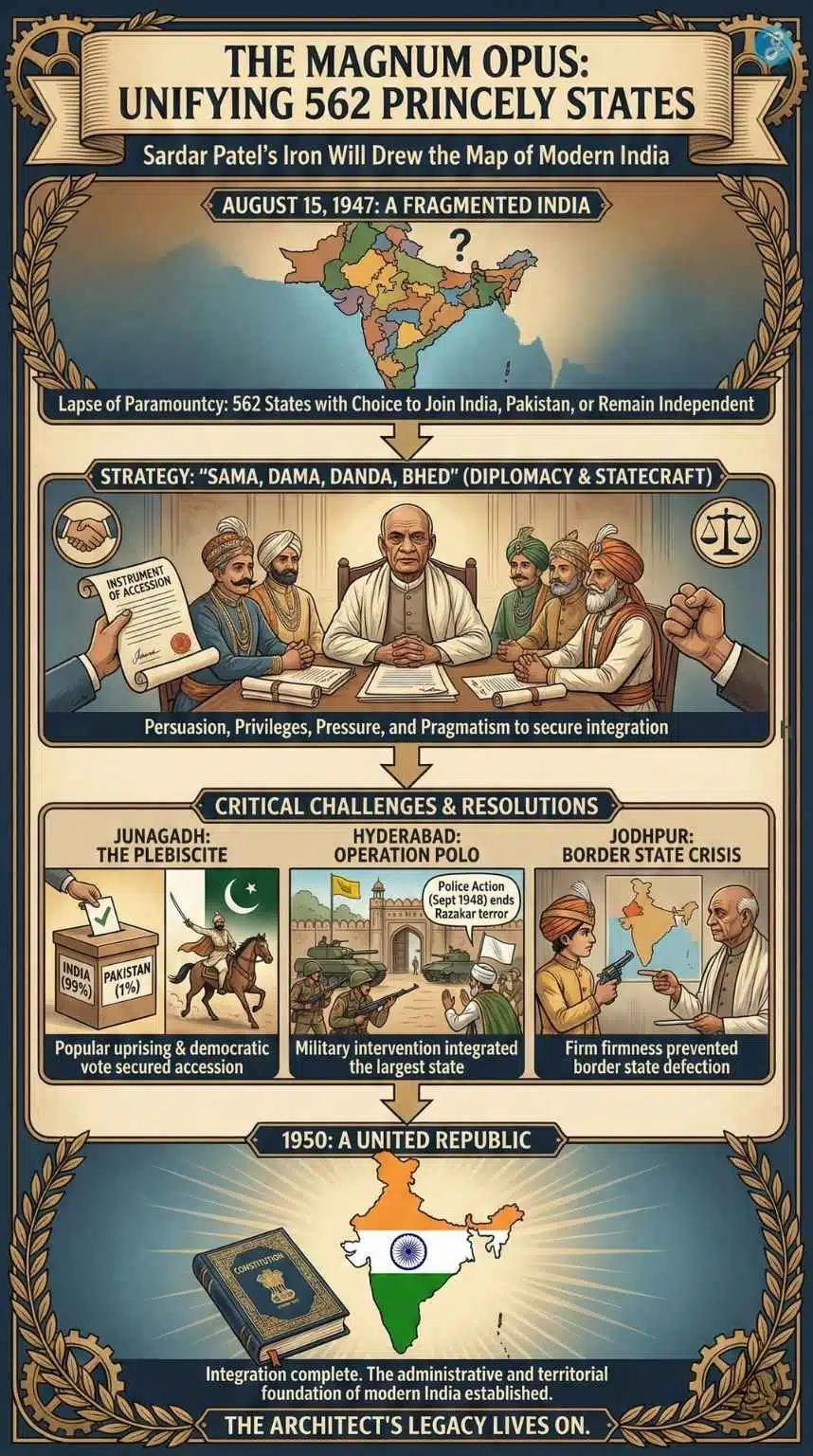

When the British flag was lowered on August 15, 1947, India was technically free, but it was not united. The Indian Independence Act had left a “lapse of paramountcy,” meaning the 562 princely states—covering 48% of the area and 28% of the population—were free to join India, join Pakistan, or, nightmare of nightmares, remain independent.

Political pundits across the world predicted the “Balkanization of India.” They believed the subcontinent would shatter into dozens of warring mini-nations. They hadn’t counted on Sardar Patel.

As the first Minister of States, Patel worked with his brilliant secretary, V.P. Menon, to execute a diplomatic miracle. His strategy was a masterclass in statecraft, often described as Sama, Dama, Danda, Bhed (Persuasion, Purchase, Punishment, and Division).

1. The Carrot and the Stick

Patel appealed to the patriotism of the princes, reminding them that they could not survive in isolation within a democratic sea. He offered them “Privy Purses”—a guaranteed income—and allowed them to retain their titles. In exchange, they had to surrender only three subjects: Defense, Foreign Affairs, and Communications.

Most signed. But three stood out as threats to India’s existence: Junagadh, Hyderabad, and Jodhpur.

2. The Revolver in Jodhpur

The Maharaja of Jodhpur, Hanwant Singh, was a young ruler who was tempted by Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Jinnah offered him a blank sheet of paper to write his own terms if he joined Pakistan. Jodhpur was a border state; its defection would have been catastrophic.

Patel acted immediately. He summoned the Maharaja to Delhi. In a dramatic encounter, the young King reportedly pulled out a revolver and pointed it at V.P. Menon, shouting, “I will not accept your dictation!” Patel, unfazed by the theatrics, calmly but firmly explained the consequences of joining Pakistan—a communal firestorm in his Hindu-majority state. The Maharaja eventually relented, signing the Instrument of Accession.

3. The Plebiscite in Junagadh

The Nawab of Junagadh, a state in Gujarat, chose to accede to Pakistan despite having an 80% Hindu population and no land connection to Pakistan. The situation was absurd. Patel encouraged a popular uprising within the state and ordered a blockade of supplies. The Nawab fled to Karachi.

Patel then arrived in Junagadh and ordered a plebiscite. The result was staggering: 190,870 votes for India and only 91 for Pakistan. It was a victory of democracy over dynastic whim.

4. Operation Polo: The Taming of Hyderabad

Hyderabad was the biggest challenge. The Nizam, Osman Ali Khan, was the richest man in the world and ruled over a state the size of France in the heart of India. He refused to join India, dreaming of an independent Islamic kingdom. His private militia, the Razakars, unleashed a reign of terror, murdering and looting the local population.

Patel’s patience wore thin. He famously declared, “We cannot have a cancer in the belly of India.” Despite hesitation from Nehru and others who feared international backlash, Patel ordered “Operation Polo” on September 13, 1948.

The Indian Army moved in. The Nizam’s forces collapsed in less than 100 hours. On September 17, the Nizam surrendered. Patel, in a gesture of immense grace, met the Nizam at the airport not as a conqueror, but as a statesman, ensuring the transition was smooth.

The Steel Frame: Patron Saint of Civil Services

While his role in unification is celebrated, Patel’s contribution to India’s governance is often overlooked. In 1947, there was a loud clamor to abolish the Indian Civil Service (ICS), which was seen as a tool of British oppression. Nehru and other leaders were skeptical of retaining the “imperial” bureaucracy.

Patel stood firm. He argued that a vast, diverse country like India could not function without a unified, professional administrative structure. He famously told the Constituent Assembly:

“You will not have a united India if you do not have a good All-India Service which has the independence to speak out its mind… If you do not adopt this course, then do not follow the present Constitution. Substitute something else.”

He rebranded the ICS as the IAS (Indian Administrative Service) and the IPS (Indian Police Service). He envisioned them as the “Steel Frame” of India—a neutral, permanent bureaucracy that would keep the nation running regardless of political changes. Today, every civil servant in India owes their existence and constitutional protection to Sardar Patel.

Architect of the Constitution

Patel’s influence extended deep into the drafting of the Indian Constitution. He served as the Chairman of the Advisory Committee on Fundamental Rights, Minorities, and Tribal and Excluded Areas.

It was Patel who championed the removal of “separate electorates”—a British divide-and-rule tactic that had crystallized communal divisions. He argued successfully that in a free India, political representation should not be based on religion. He balanced the rights of minorities with the need for a cohesive national identity, ensuring that the Constitution was a document of unity, not division.

The Crisis Manager: Kashmir, Partition, and Somnath

Beyond the maps and laws, Patel was India’s ultimate crisis manager. His pragmatism often clashed with the idealism of others, but it was this very quality that saved the nation from collapse.

The Savior of Kashmir

While the political handling of Kashmir is often attributed to Prime Minister Nehru, the military defense of the region was Patel’s triumph. In October 1947, as Pakistani-backed tribesmen closed in on the Srinagar airfield, the Indian leadership was paralyzed by diplomatic protocols. It was Patel who cut through the hesitation.

In a decisive meeting, he reportedly told the military commanders, “Do not wait. We must save Kashmir.”

He organized the massive airlift of Indian troops to Srinagar at dawn, securing the airport just minutes before the invaders could seize it. Without his logistical genius, the valley might have been lost entirely.

The Bitter Pill of Partition

History often forgets that Sardar Patel was one of the first Congress leaders to accept the inevitability of Partition. While it pained him, he was a realist. He realized that the Muslim League’s obstructionism within the Interim Government was paralyzing the country.

He famously argued that it was better to have a clean separation than to have “a cancer in the body politic of India” that would lead to constant civil war. He chose a smaller, stronger India over a larger, chaotic one.

Resurrecting Somnath

Patel’s vision extended beyond borders to the soul of the civilization. On a visit to Junagadh, he visited the ruins of the Somnath Temple, which had been destroyed and rebuilt repeatedly over centuries. Standing amidst the rubble, he pledged that a free India would rebuild the temple to its former glory.

Despite opposition from those who viewed it as religious revivalism, Patel maintained that the reconstruction was an act of national pride, not just religious piety.

He famously said, “By rising from the ashes, the Somnath is proclaiming that the power of creation is always greater than the power of destruction.”

The Final Farewell: December 15, 1950

By 1950, Patel’s health was failing. The “Iron Man” was physically frail, though his spirit remained unbroken. He moved to Bombay (now Mumbai) to recover, staying at Birla House.

On the morning of December 15, 1950, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel suffered a massive heart attack. He passed away at 9:37 AM. The news sent a shockwave through the nation.

His funeral in Bombay was attended by a massive crowd estimated at 1.5 million people. They lined the streets, climbed trees, and filled rooftops to catch a glimpse of the cortege. In a touching break from protocol, President Dr. Rajendra Prasad attended the funeral. When advised that the President should not attend the funeral of a Minister, Prasad replied that his bond with Patel transcended protocol—they were brothers in arms long before they were office bearers.

Legacy: The Eternal Sardar

Today, the Statue of Unity stands in Gujarat, rising 182 meters into the sky—the tallest statue in the world. It is a fitting monument to a man whose stature was truly colossal.

But his real monument is the map of India itself. Every time we travel from Kashmir to Kanyakumari without needing a visa, every time a civil servant upholds the law against political pressure, and every time the Indian flag flies over a united republic, we are living in the legacy of Vallabhbhai Patel.

He was a man who did not seek popularity; he sought results. He did not charm; he convinced. He did not just dream of a great India; he built it, brick by brick, state by state.

“Faith is of no avail in absence of strength. Faith and strength, both are essential to accomplish any great work.” — Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel

On this death anniversary, we honor the man who proved that while revolutions are started by idealists, nations are built by realists.

Frequently Asked Questions About Vallabhbhai Patel

1. Why is Vallabhbhai Patel called the “Iron Man of India”?

He earned this title for his uncompromising resolve and leadership in integrating 562 fragmented princely states into a single, unified nation after independence.

2. What was Sardar Patel’s role in the Indian Civil Services?

Patel is known as the “Patron Saint” of the civil services because he established the modern IAS and IPS, envisioning them as the “Steel Frame” to keep India united.

3. How did Sardar Patel handle the Hyderabad crisis?

When the Nizam refused to join India and his militia caused violence, Patel ordered “Operation Polo” in 1948, a swift five-day police action that secured Hyderabad’s accession.

4. Where is the Statue of Unity located, and what does it represent?

Located in Gujarat, it is the world’s tallest statue (182 meters), symbolizing Patel’s colossal contribution to the political and territorial integrity of modern India.

5. Did Sardar Patel support the Partition of India?

Yes, he was one of the first Congress leaders to accept Partition as a bitter necessity, realizing that a divided but strong India was better than a united but weak nation paralyzed by civil war.

Final Words: A Tribute, Not A Myth

It’s easy to turn historic leaders into flawless icons. A better tribute is more human and more meaningful: to remember Patel as a man who worked under extreme pressure, made difficult choices, and carried the heavy burden of unity at the most fragile moment of India’s history.

On 15 December, remembering Vallabhbhai Patel is not only about praising the past. It is about renewing a commitment that remains unfinished in every generation: keeping India united—through fairness, discipline, and courage.