How do directors use cinematography to tell stories and shape what you feel before a character even speaks? The short answer is that cinematography turns ideas into visual choices that guide attention, build emotion, and reveal meaning. It is not just about making a film look “good.” It is about making the story readable, memorable, and emotionally precise.

In this guide, you’ll learn the practical ways directors and cinematographers use camera, light, lens, color, and movement to communicate a story. You’ll also see how these tools connect directly to character, pacing, tension, and theme.

What Cinematography Really Does in Storytelling?

Cinematography is the language of images. It decides what the audience sees, how they see it, and how long they sit with it. A director uses this language to shape interpretation, even when the plot stays the same.

If you change only the framing, lighting, and camera motion of a scene, you can change its meaning completely. A friendly conversation can feel threatening. A victory can feel hollow. A home can feel safe or haunted. That power comes from controlling three things: attention, emotion, and context.

Cinematography usually supports storytelling in a few core ways:

-

Directing attention: guiding your eyes toward what matters

-

Creating emotion: making a moment feel intimate, tense, warm, cold, chaotic, or calm

-

Revealing character: showing power dynamics, vulnerability, confidence, isolation, or instability

-

Building world and tone: defining whether a film feels grounded, dreamy, gritty, romantic, or surreal

-

Controlling rhythm: shaping pacing through shot length and movement style

A useful mindset is this: dialogue tells you what characters say, but images often tell you what they mean.

How Directors Plan Visual Storytelling Before Shooting?

A lot of cinematic storytelling happens before anyone presses record. Directors work with cinematographers to decide the visual rules of the film, so choices feel consistent and intentional rather than random.

Here are a few planning tools that shape the final look:

-

Storyboards: rough sketches of shots and key moments

-

Shot lists: a blueprint of what needs to be filmed and how

-

Look references: visual inspiration for lighting, color, and framing

-

Blocking plans: where actors move and how the camera responds

-

Visual motifs: repeating shapes, colors, angles, or movements that reinforce the theme

This planning stage is where a director answers questions like:

Should the camera feel invisible or present? Should the world feel natural or stylized? Should the audience feel like a witness or a participant?

When a film has a strong visual identity, it usually comes from a set of decisions made early, then repeated with purpose.

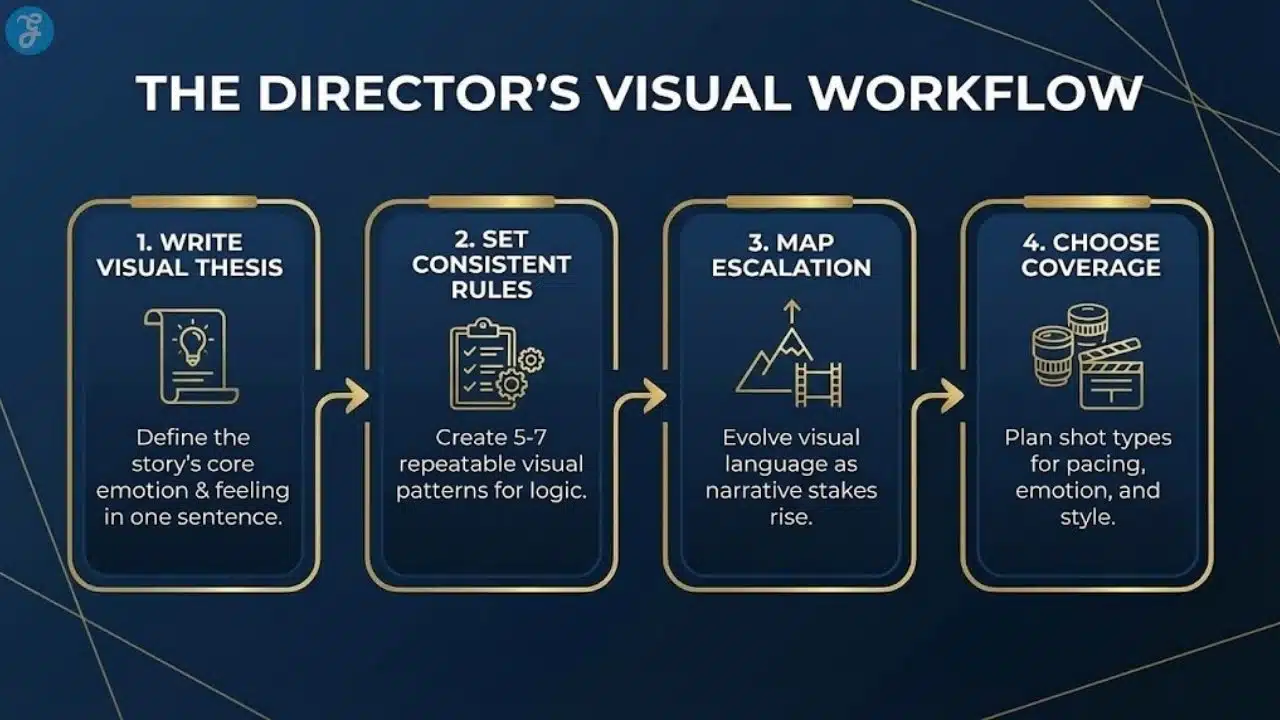

The Director–Cinematographer Workflow That Prevents Random Visual Choices

A lot of films look “stylish” but still feel emotionally flat because the visuals don’t follow a coherent logic. The difference between pretty cinematography and storytelling cinematography is usually a shared workflow: the director defines intent, and the cinematographer translates that intent into repeatable visual rules.

A useful way to think about it is every major story beat should have a visual plan—even if the plan is “stay simple and invisible.” Here’s a simple 4-step workflow directors use

1) Write a one-sentence visual thesis

This isn’t about gear. It’s about feeling.

-

“This story should feel like someone is always being watched.”

-

“This story should feel warm until it breaks.”

-

“This story should feel controlled, then increasingly unstable.”

2) Set 5–7 visual rules that stay consistent

Examples (steal these patterns):

-

The camera is mostly locked off until the protagonist lies.

-

Warm light = safety. Cold light = threat.

-

The protagonist is centered only when confident and off-center when anxious.

-

Close-ups are “earned” only at turning points.

-

Handheld appears only when the character loses control.

3) Map visual escalation scene-by-scene

If the stakes rise, the imagery language should evolve too. “Escalation” can mean tighter framing, harsher shadows, faster movement, or color shifts. The point is change with purpose, not change for variety.

4) Choose a coverage philosophy

This affects pacing and emotion more than most people realize:

| Coverage style | What it’s best for | What it risks |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional coverage (wide/medium/close) | Clarity, editorial flexibility, dialogue scenes | Generic visuals if not motivated |

| Designed coverage (specific planned shots) | Strong meaning, stronger tone, visual motifs | Less flexibility if performance changes |

| Long-take / minimal cutting | Immersion, tension, performance-driven scenes | Can feel self-indulgent if not earned |

Bottom line: When cinematography feels intentional, it’s usually because the film has rules—and those rules are tied to character and theme.

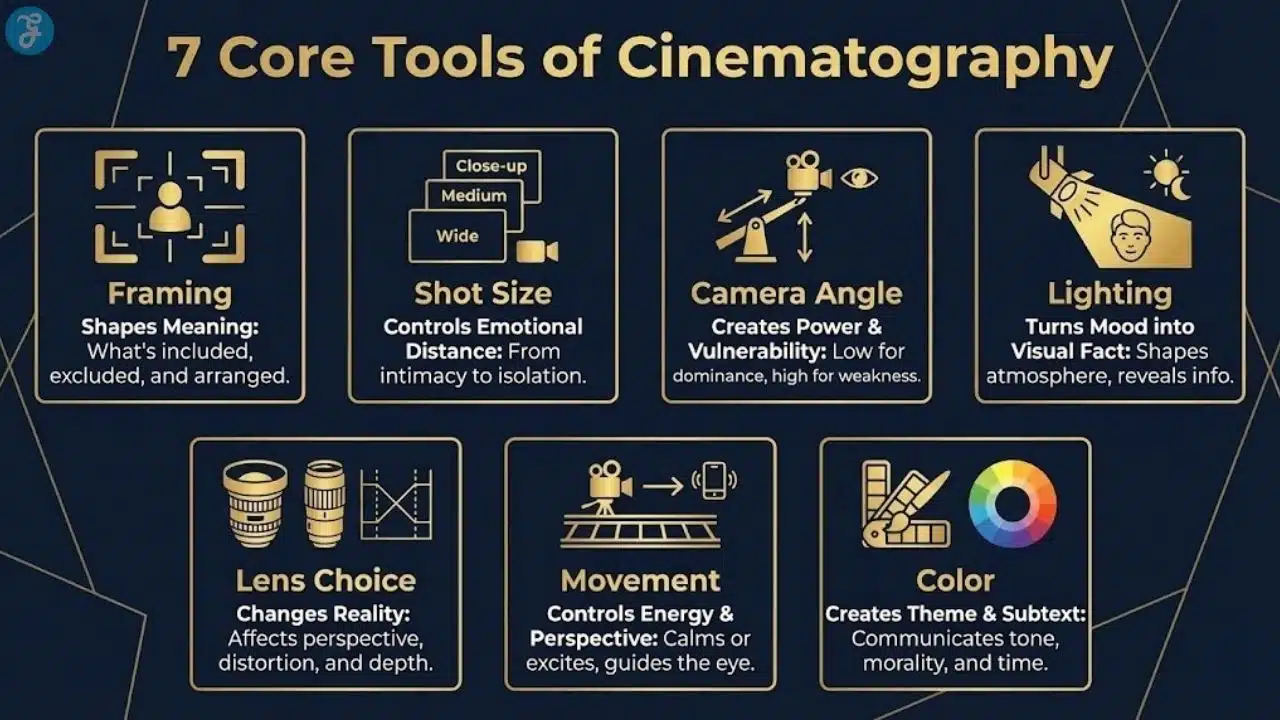

7 Tools Directors Use in Cinematography to Tell Stories

These are the most common storytelling tools used across genres. They work in blockbusters, dramas, thrillers, indie films, and documentaries. What changes is how boldly they’re used.

1. Framing and Composition Shape Meaning

Framing is what you include in the shot and what you exclude. Composition is how elements are arranged inside the frame. Together, they control how we interpret relationships, danger, intimacy, and power.

Small framing changes can shift the emotional message:

-

A character centered with space around them can feel calm, important, or lonely

-

A character pushed to the edge of frame can feel trapped or unstable

-

A character blocked by objects can feel controlled, watched, or hidden

-

Two characters framed symmetrically can feel connected or in conflict

Directors also use composition to guide the eye. Lines, contrast, and movement can pull attention toward a face, a weapon, a doorway, or a clue without any dialogue.

A scene can “tell” you who holds power simply by how bodies occupy the frame.

2. Shot Size Controls Emotional Distance

Shot size is one of the clearest storytelling levers. It determines how close you feel to a character and how much of the world you understand.

Common shot sizes and what they often communicate:

-

Extreme wide shot: isolation, scale, fate, danger, or awe

-

Wide shot: relationships between people and the environment

-

Medium shot: balanced intimacy and context, often conversational

-

Close-up: vulnerability, intensity, revelation, tension

-

Extreme close-up: obsession, discomfort, detail, psychological pressure

A director might stay wide to keep you emotionally distant. Or they might cut to a close-up at a key moment to force you into a character’s inner world. Used well, shot size becomes emotional pacing.

3. Camera Angle Creates Power and Vulnerability

Angles shape how we subconsciously judge a character. A slight tilt, a low angle, or a high angle can change the emotional hierarchy of a scene.

Typical effects include:

-

Low angle: dominance, threat, heroism, control

-

High angle: weakness, exposure, fear, loss of control

-

Eye level: neutrality, realism, equality

-

Dutch angle (tilt): instability, unease, tension, disorientation

Directors don’t always use these as clichés. Sometimes they invert them. A high angle can be used to suggest emotional detachment, not weakness. A low angle can be used to show how someone feels powerful, even if they are not.

The key is consistency. When angles follow a story logic, they become a quiet narrator.

4. Lighting Turns Mood Into a Visual Fact

Lighting is not just visibility. It is mood, time, and meaning.

Directors and cinematographers use lighting to:

-

Shape how safe or unsafe a space feels

-

Reveal or hide information

-

Make a moment feel romantic, clinical, nostalgic, or ominous

-

Suggest honesty, secrecy, guilt, or transformation

A few common lighting approaches include:

-

Soft light: gentle, flattering, intimate, calmer emotion

-

Hard light: sharp shadows, tension, conflict, intensity

-

Low-key lighting: strong contrast, mystery, suspense, noir tones

-

High-key lighting: bright, open, comedic, or light emotional tone

-

Backlighting: silhouette, mystery, spiritual, or dramatic effect

Lighting can also act like character psychology. A person stepping into the shadow can signal secrecy or moral decline. A face lit evenly can signal openness or innocence.

When the lighting shifts, the story often shifts with it.

5. Lens Choice Changes Reality Itself

Lens choice affects perspective, distortion, depth, and the emotional feel of a shot. This is one of the most underappreciated storytelling tools for viewers, because it’s subtle when done well.

In simple terms:

-

Wide lenses can make spaces feel larger and movement feel faster. They can also distort faces up close, which can feel uncomfortable or intense.

-

Telephoto lenses compress space, making background elements feel closer. They can isolate a character from their environment and create a voyeur-like feel.

Lens choice also influences depth of field:

-

Shallow depth of field isolates a subject and reduces distraction. It can feel intimate or dreamlike.

-

Deep focus keeps more of the scene sharp. It can make the world feel real, busy, or overwhelming.

When directors want you to feel inside a character’s head, lens and focus choices often do the heavy lifting.

How do directors use cinematography in a way you can feel without noticing? Lens decisions are one of the biggest reasons.

6. Camera Movement Controls Energy and Perspective

Movement tells the audience how to experience a moment. It can feel calm, aggressive, anxious, elegant, or chaotic.

Here are common movement styles and what they often suggest:

-

Locked-off camera: stability, formality, observation, tension through stillness

-

Handheld: immediacy, realism, instability, urgency

-

Steadicam or smooth tracking: immersion, elegance, dreamlike flow

-

Push-in (slow move closer): realization, pressure, emotional emphasis

-

Pull-back (move away): isolation, defeat, emotional distance

Movement also signals viewpoint. A smooth camera can feel like a guiding narrator. A shaky camera can feel like a frightened witness. A slow, controlled move can feel like fate closing in.

The most effective movement matches the story’s emotional temperature.

7. Color and Contrast Create Theme and Subtext

Color is not decoration. It is information.

Directors use color to communicate:

-

Emotional tone (warmth vs coldness)

-

Moral or psychological shifts (purity vs corruption)

-

Time periods and memory states

-

Symbolic motifs tied to character arcs

Color can be used in obvious ways, like a repeating red element tied to danger. But it is often used subtly through production design, wardrobe, and lighting temperature.

Contrast matters too. A high-contrast look can feel harsh and tense. A muted palette can feel realistic, tragic, or subdued. A saturated palette can feel playful, heightened, or surreal.

When color is consistent, it becomes a storytelling thread the audience feels even if they can’t name it.

How Cinematography Supports Character and Theme?

Great cinematography is not separate from story. It is a story.

Directors use visual tools to reflect internal character states. A character who feels trapped might be filmed through doorframes, mirrors, fences, or narrow hallways. A character who gains confidence might be shown with stronger lighting, steadier movement, and more centered framing.

Theme also becomes visible through repeated visual patterns. If a film is about control, you might see rigid symmetry and locked frames. If it is about uncertainty, you might see unstable angles and shifting focus. If it is about isolation, you might see wide compositions that swallow a character in their environment.

This is why viewers often describe “vibes” without knowing why. The visuals are doing narrative work beneath dialogue.

Point of View Cinematography: Who Is the Camera “Loyal” To?

Every shot implies perspective. Even if the camera isn’t literally a character’s eyes, the director still decides whether the camera feels like a witness, a participant, or a judge.

This matters because POV is an emotional contract. The camera can align us with a character—or keep us distant enough to critique them. The 3 POV modes directors switch between:

1) Objective (observer camera)

The camera feels neutral, like we’re simply watching.

-

Often uses balanced framing, steady movement, and readable geography.

-

Works well when the director wants the audience to judge for themselves.

2) Subjective (inside a character’s emotion)

The camera feels closer, more personal, and sometimes unstable.

-

Often uses closer shot sizes, shallow depth of field, tighter framing, or handheld.

-

Works well for anxiety, obsession, intimacy, or fear.

3) Authorial / omniscient (the film “commenting”)

The camera feels composed, symbolic, and deliberate.

-

Often uses strong composition, motif-based lighting, or “statement” angles.

-

Works well when the theme is the priority and visuals carry metaphor.

How POV shifts can signal character development

A clean way to show change without dialogue:

-

early: distant, observational framing (we don’t know them yet)

-

middle: closer, more subjective framing (we empathize)

-

late: either intimate (connection) or distant (loss/alienation)

Quick tell: How to spot POV control as a viewer

If the scene feels tense before anything happens, ask:

-

Is the camera hunting (slow push-in)?

-

Is it hiding (obstructions, distance)?

-

Is it judging (high angle, cold lighting)?

Those choices often reveal what the director wants you to feel about the character.

How do Directors Use in Cinematography Differently by Genre?

The same tools serve different goals depending on the genre. A close-up in a romance reads differently than a close-up in a horror film.

A few broad genre patterns:

-

Horror: shadows, negative space, slow pushes, restricted visibility

-

Action: energetic movement, clear geography, dynamic angles, fast rhythm

-

Drama: restrained movement, naturalistic lighting, intimate framing

-

Comedy: brighter lighting, wider framing for physical timing, clearer staging

-

Thriller: contrast, controlled movement, selective focus, uneasy compositions

These are not rules, but they are common strategies. The best directors break expectations when it supports story, not when it serves style for its own sake.

One Simple Way to “Read” Cinematography While Watching

If you want to understand visual storytelling quickly, focus on three questions during key scenes:

-

What am I being asked to look at?

-

How close do I feel to the character, and why?

-

Does the camera feel calm, nervous, or controlled?

You don’t need technical vocabulary to notice patterns. Once you start spotting consistency, you’ll see how intentional the visual language is.

If you’re watching a scene and you suddenly feel tension, intimacy, or dread before anything “happens,” it’s usually because the cinematography has already started telling the story.

Common Cinematography Mistakes That Hurt Story

Readers love this because it turns theory into action fast—and it naturally lengthens the article without fluff.

Mistake: visuals that look cool but don’t mean anything

Fix: assign each technique a job: hide/reveal, comfort/threaten, connect/isolate, and escalate/relieve.

Mistake: constant camera movement

Fix: move only when something changes—power shifts, information shifts, or emotion shifts. Otherwise movement becomes noise.

Mistake: random lens choices

Fix: create a lens logic. Wide-and-close often feels intense or uncomfortable; long-and-distant often feels voyeuristic or isolating. Use that intentionally.

Mistake: no visual escalation

Fix: make the visual language evolve with stakes—tighter framing, stronger contrast, colder palette, shakier movement (or, if theme is control, more rigid movement).

Final Thoughts

Directors do not use cinematography to impress you with technique. They use it to control meaning. Every choice, framing, light, lens, color, and movement shapes what you understand and what you feel. How Do Directors Use Cinematography becomes easier to answer when you watch films as visual arguments, not just plotted events.

When the visuals match the emotional truth of a scene, the audience believes the story more deeply. That is the real power of cinematography.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Here are some of the most frequently asked questions among readers:

What Is the Difference Between Cinematography and Videography?

Cinematography is focused on storytelling choices in a film language, including lighting, composition, and camera movement. Videography is often a broader term for recording events or content, which may not be built around narrative intent.

Do Directors or Cinematographers Make These Choices?

Both. Directors guide story intent and tone, while cinematographers shape how those ideas become visual reality. The strongest results come from close collaboration and clear shared goals.

Can Great Cinematography Save a Weak Script?

It can improve the experience, but it cannot fully replace strong storytelling foundations. Cinematography can add emotion and clarity, yet character logic and structure still matter.

Why Do Some Movies Look “Cinematic” Even Without Big Budgets?

Because “cinematic” often comes from intentional choices, not expensive gear. Strong framing, motivated lighting, and consistent visual rules can elevate low-budget work significantly.

How Can Beginners Learn Cinematography Faster?

Start by studying scenes and pausing to analyze framing, lighting, and movement. Then practice recreating simple shots with one light source and a clear subject. The fastest learning comes from repetition and review.