In early 2026, trade policy is being rewritten around security. Tariffs and controls now cover trillions in imports, and firms are duplicating supply chains to avoid geopolitical shocks and tech choke points. What is sold as “de-risking” is starting to look like a new, quieter Iron Curtain.

Key Takeaways

- “De-risking” is no longer a slogan. It is becoming an operating system for trade, investment, technology, and diplomacy.

- The world is not splitting cleanly into two camps. Instead, it is forming overlapping blocs with selective, strategic separation in critical sectors.

- The biggest economic effect is not a sudden collapse in trade. It is a slow tax on efficiency: higher costs, slower diffusion of technology, and more policy-driven investment.

- Winners are likely to be “connector” economies that can supply multiple blocs, while “single-market dependent” economies face higher volatility and bargaining pressure.

- 2026 is shaping up as a checkpoint year, with major policy milestones and institutional stress tests that will determine whether fragmentation stabilizes or escalates.

How We Got Here: From Hyper-Globalization to Security-First Trade?

The phrase “New Iron Curtain” is provocative because it calls back to the Cold War, when political ideology hardened into military alliances and trade barriers. Today’s version is more subtle and more commercial. There is no single wall, no universal embargo, and no clean split that separates two self-contained economic systems. Instead, the global economy is developing selective partitions: a handful of sectors where states are deliberately limiting dependence, restricting technology flows, and reshaping investment rules.

This shift has been years in the making. The arc begins with the peak optimism of the 1990s and early 2000s, when global supply chains expanded rapidly. Production moved to wherever it was cheapest and most scalable. Trade agreements grew. Firms treated geopolitics as a background risk, not a central business variable.

Then the assumptions started breaking.

The 2008 financial crisis weakened trust in the model of frictionless markets. It did not end globalization, but it did change its politics. The distributional effects became harder to ignore, especially in advanced economies where manufacturing employment had already been declining.

The next shock was strategic, not financial. As China rose as a manufacturing powerhouse and a technology competitor, trade stopped looking like neutral commerce and started looking like leverage. In the United States and Europe, policy debates moved from “How do we trade more?” to “What do we become dependent on, and what could be weaponized against us?”

COVID-19 was a turning point because it exposed a fragile truth: global supply chains were optimized for cost, not resilience. Shortages in medical supplies and semiconductors made security planners and corporate boards talk in the same language for the first time. Resilience became a strategic goal, not just an operational preference.

The Russia–Ukraine war and the sanctions response accelerated the trend. It demonstrated how quickly financial channels, energy markets, and high-tech imports could become instruments of statecraft. For many governments, the lesson was clear: the real risk is not only disruption, it is coercion.

By 2023, “de-risking” became the compromise phrase. Leaders wanted to signal that they were not pursuing full “decoupling,” but they still wanted to justify sharper controls. The G7’s language captured this balancing act: protect security, reduce vulnerabilities, and keep markets open where possible.

Europe formalized the idea with an “economic security” approach that treated supply chains, critical infrastructure, sensitive technologies, and coercion risks as a single policy domain. That approach has since spread, influencing how allies coordinate, how rival powers respond, and how middle powers position themselves.

A crucial point is that today’s fragmentation is not mainly about tariffs alone. It is about the deep rules of the modern economy: export controls, investment screening, subsidy regimes, data governance, and industrial policy. These tools can reshape trade even without traditional protectionism.

Here is a compact timeline that shows how the current moment emerged:

| Period | Trigger | What Changed In Policy Thinking | Lasting Effect On Trade |

| 2008–2012 | Global financial crisis | Markets seen as unstable; inequality politics rise | More domestic pressure for “managed” trade |

| 2016–2019 | US–China trade and tech rivalry intensifies | China seen as strategic competitor, not just partner | Tariffs and tech controls normalize |

| 2020–2021 | COVID-19 and supply chain shocks | Resilience becomes national security | “Just-in-time” begins to fade in critical sectors |

| 2022–2023 | Ukraine war and sanctions era | Energy, finance, and tech are weaponized | Firms start pricing geopolitics into strategy |

| 2024–2026 | Economic security strategies expand | Investment, data, and tech policy converge | Fragmentation becomes structural, not temporary |

The big story, then, is not a single event. It is a new governing logic: states are reasserting control over interdependence, especially where they believe vulnerability could be exploited.

How Does Global Trade De-Risking Work in Practice?

“De-risking” sounds like a safety checklist. In practice, it is a redesigned map of what is “allowed,” “discouraged,” or “blocked” in global commerce. It works through a toolkit that reaches deeper into the economy than older trade barriers.

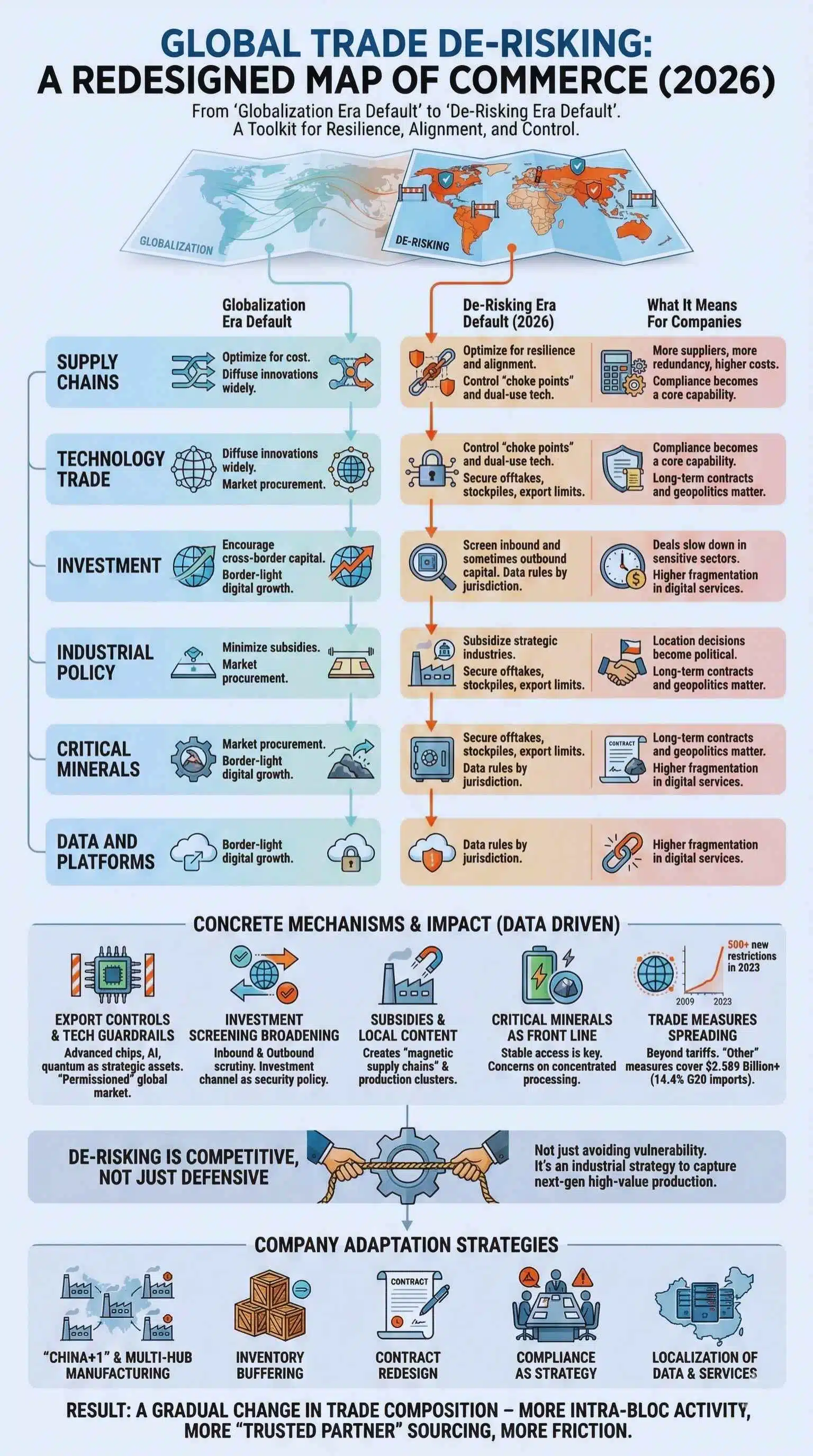

A useful way to understand this is to see how the de-risking playbook differs from the globalization playbook.

| Policy Area | Globalization Era Default | De-Risking Era Default (2026) | What It Means For Companies |

| Supply chains | Optimize for cost | Optimize for resilience and alignment | More suppliers, more redundancy, higher costs |

| Technology trade | Diffuse innovations widely | Control “choke points” and dual-use tech | Compliance becomes a core capability |

| Investment | Encourage cross-border capital | Screen inbound and sometimes outbound capital | Deals slow down in sensitive sectors |

| Industrial policy | Minimize subsidies | Subsidize strategic industries | Location decisions become political |

| Critical minerals | Market procurement | Secure offtakes, stockpiles, export limits | Long-term contracts and geopolitics matter |

| Data and platforms | Border-light digital growth | Data rules by jurisdiction | Higher fragmentation in digital services |

The mechanics show up in several concrete ways.

First, export controls and technology guardrails. Advanced chips, chipmaking equipment, AI infrastructure, and quantum technologies are increasingly treated as strategic assets. Governments frame this as preventing military modernization by rivals and protecting domestic innovation. The practical outcome is that firms now face a “permissioned” global market: what you can sell, to whom, and with what technical specifications is becoming more regulated.

Second, investment screening is broadening. Inbound screening is now common across many advanced economies. The newer and more consequential shift is outbound scrutiny, where governments worry about domestic capital and know-how building up strategic rivals. Europe’s approach has moved toward coordinated reviews in key technologies, signaling that the investment channel is no longer separate from security policy.

Third, subsidies and local content rules shape trade indirectly. Instead of blocking imports outright, states tilt the playing field so production clusters domestically or within allied networks. This creates “magnetic supply chains,” where incentives pull factories and upstream suppliers into preferred jurisdictions.

Fourth, critical minerals are becoming the front line. The clean energy transition and the AI hardware boom both depend on stable access to minerals and industrial inputs. Governments increasingly worry about concentrated processing capacity and potential export restrictions.

The data already show how fast this is moving. The OECD’s inventory of export restrictions on industrial raw materials reports that such restrictions increased more than fivefold between 2009 and 2023, with a sharp acceleration in 2023 that added over 500 new raw material products with at least one restriction. Separately, OECD analysis also highlights that between 2021 and 2023, 14% of global trade in non-waste and scrap industrial raw materials faced at least one export restriction. Those are not marginal numbers. They suggest a systematic move toward treating upstream inputs as strategic assets rather than neutral commodities.

Fifth, trade measures are spreading beyond tariffs into “other” restrictions. A joint monitoring summary by the WTO, OECD, and UNCTAD covering mid-October 2024 to mid-October 2025 reports that the trade covered by import-related “other” measures increased more than fourfold to about USD 2,589 billion, representing 14.4% of G20 merchandise imports. Even without listing every policy instrument, that figure signals scale: the policy footprint on trade is now measured in the trillions.

What makes the current phase different is that it is not simply defensive. It is also competitive. De-risking policies are often framed as protection, but they also serve as industrial strategy. Countries are not only avoiding vulnerability; they are trying to capture the next generation of high-value production.

Companies adapt in predictable ways:

- “China+1” and multi-hub manufacturing: Firms add capacity in alternative locations to reduce single-country exposure.

- Inventory buffering: More stockpiling for critical inputs, especially where policy shifts can cut off access quickly.

- Contract redesign: More clauses tied to sanctions, export controls, and sudden tariff changes.

- Compliance as strategy: Trade compliance teams are moving from back-office functions to board-level risk management.

- Localization of data and services: Digital trade increasingly faces national rules, pushing firms to build separate stacks by region.

The result is not an immediate collapse in global trade volumes. It is a gradual change in how trade is composed: more intra-bloc activity, more “trusted partner” sourcing for sensitive inputs, and more friction for cross-bloc technology and capital flows.

Economic Impact: Slower Trade, Costlier Capital, And Uneven Winners

The most important economic effect of the “New Iron Curtain” is not that trade disappears. It is that the efficiency dividend of globalization shrinks. When firms duplicate supply chains, when governments subsidize strategic industries, and when technology diffusion slows, the global economy pays a quiet cost over time.

Recent official forecasts and monitoring snapshots point to the same story: resilience is holding, but momentum is weakening.

- The WTO’s October 2025 update raised its forecast for world merchandise trade volume growth in 2025 to 2.4%, but it lowered its estimate for 2026 to 0.5%. That downgrade matters because it suggests that the world is entering a period where policy uncertainty and tariffs have delayed effects that show up later, not immediately.

- The World Bank’s Global Economic Prospects press release (January 13, 2026) describes “historic trade and policy uncertainty” and projects global growth easing to around 2.6% over the next two years. It also flags a sobering distributional reality: roughly one in four developing economies remains poorer than it was in 2019.

- UN DESA’s World Economic Situation and Prospects 2026 notes a “stable but subdued” outlook, clouded by uncertainty, shifting trade policies, and geopolitical tensions.

- UNCTAD’s World Investment Report 2025 finds that global FDI fell by 11% in 2024. Reported flows were about $1.5 trillion, but UNCTAD notes this is inflated by volatile conduit flows, meaning the underlying trend is weaker than the headline. It also highlights sharp regional divergence, including a contraction in developed economies and notable declines in Europe and China.

A compact data snapshot helps show the direction of travel:

| Indicator (Latest Available) | What It Shows | Why It Matters For De-Risking |

| WTO merchandise trade growth forecast: 2025 at 2.4%, 2026 at 0.5% | Trade is not collapsing, but it is slowing sharply | Policy shocks and tariff uncertainty can hit with a lag |

| G20 import-related measures covering about USD 2,589B (mid-Oct 2024 to mid-Oct 2025) | Trade policy footprint has expanded fast | Measures are scaling to “system size,” not niche sectors |

| OECD raw material export restrictions: more than fivefold rise (2009–2023), 500+ products added in 2023 | Resource nationalism is accelerating | Critical inputs can be weaponized or withheld |

| UNCTAD: global FDI fell 11% in 2024 | Investment is becoming more cautious and political | Fragmentation often shows up first in capital flows |

| World Bank: global growth around 2.6% (2026 outlook) | Resilient but sluggish growth | Higher friction reduces convergence and productivity gains |

The deeper economic story is about risk premia. In the old model, firms used global integration to lower costs and increase scale. In the new model, firms treat policy risk as a permanent variable. That changes financing, valuation, and investment horizons.

Capital becomes choosier. Investors increasingly price country risk, sanctions exposure, and regulatory unpredictability. Projects that would have been profitable under stable trade rules become marginal when you add compliance costs, potential export bans, or forced technology localization.

Trade reallocation accelerates, but with inefficiency. When firms move production out of a high-risk jurisdiction, they often move it to a higher-cost jurisdiction. The trade continues, but with more expensive inputs. That raises final consumer prices or compresses margins.

Innovation diffusion slows. Even when controls are targeted, the indirect effects can be broad. If advanced tools and research collaboration fragment, the global innovation system becomes less integrated. That matters for productivity growth, the main driver of long-run living standards.

Fragmentation acts like a productivity tax. The IMF has warned in multiple analyses that deeper fragmentation could reduce global output significantly over the long run. Even if headline numbers vary, the direction is consistent: splitting into rival blocs lowers efficiency and raises duplication.

Yet the impact is not evenly distributed. Fragmentation creates opportunities as well as costs.

Some economies are positioned as “connectors” that can attract investment from multiple sides. Others are at risk because they are too dependent on a single market or a narrow export basket. The difference is not ideology. It is economic geometry.

Here is a simplified “winners and losers” map, with an important caveat: this is about relative positioning under de-risking pressures, not moral judgment or permanent destiny.

| Likely Beneficiaries | Why | Economies Under Pressure | Why |

| “Connector” manufacturing hubs | Can serve multiple blocs, attract diversification | Single-market dependent exporters | Vulnerable to tariffs, sanctions, and bargaining pressure |

| Critical minerals producers with stable governance | Can negotiate long-term supply deals | Countries relying on cheap imported energy or inputs | Price shocks and trade restrictions hit hard |

| Economies with strong compliance and legal infrastructure | Firms prefer predictable rule environments | Exporters in sensitive tech supply chains | High risk of controls, licensing, and sudden bans |

| Regions with large domestic markets | Can sustain scale even with less openness | Small open economies without strategic leverage | Fragmentation raises their costs without compensating inflows |

Even within the same country, the effects can diverge. Large firms with compliance teams and diversified markets can adapt. Smaller exporters and suppliers often cannot absorb the extra friction.

The political economy consequence is also significant. When the gains from trade become more uneven, public support for openness can erode further, reinforcing the cycle that led to de-risking in the first place.

Diplomatic Decoupling: Blocs, Middle Powers, And The New Nonalignment

Trade de-risking is not only economic policy. It is diplomacy by other means.

During the Cold War, alliances largely determined trade. Today, trade policies are increasingly shaping alliances. Countries use market access, technology partnerships, and infrastructure finance as instruments of influence. This is why the “New Iron Curtain” analogy resonates: the world is not only competing in markets, it is competing over the rules that decide who can participate in which parts of the economy.

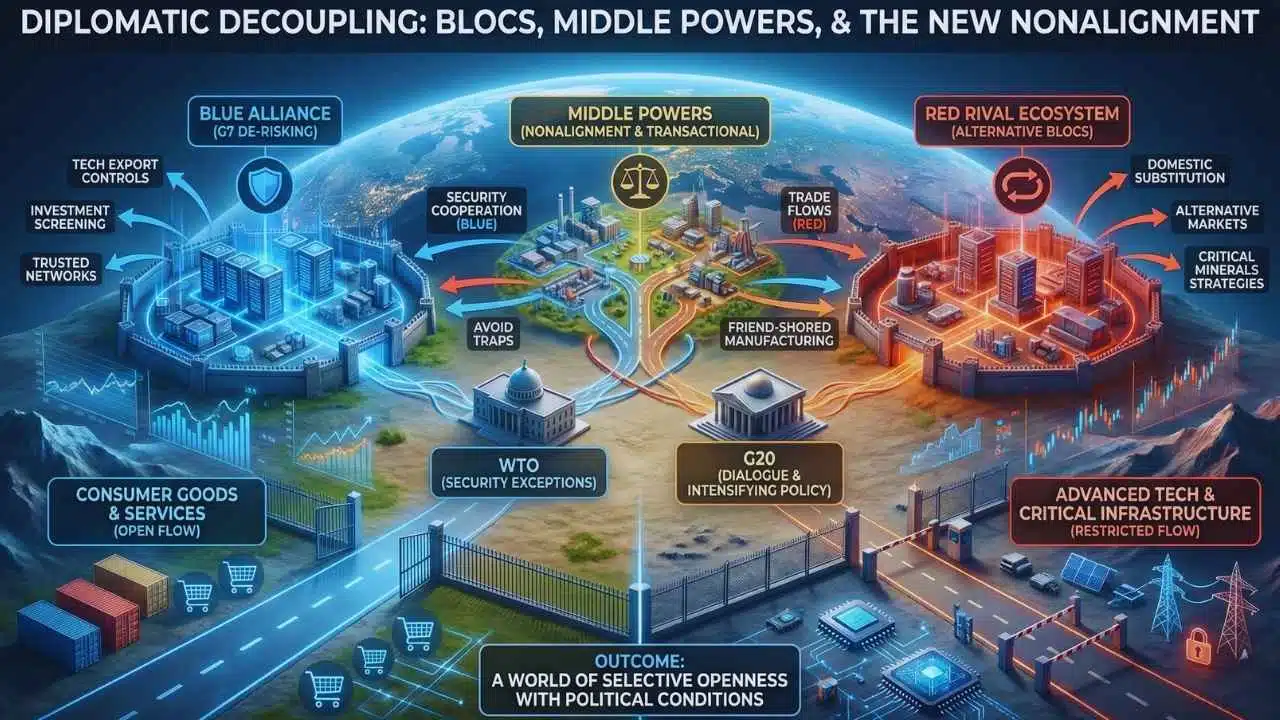

But the modern world is more complex than a binary split. Three overlapping dynamics are shaping the new landscape.

1) Allies are coordinating economic security policy.

The G7 framing of “de-risking” signaled a shared direction: protect key technologies, reduce dependencies, and respond to coercion while avoiding an explicit commitment to full decoupling. That language has since been echoed in industrial and trade measures that push supply chains toward trusted networks.

2) Rivals are building alternative ecosystems.

When one bloc restricts technology or investment flows, the other bloc responds by accelerating domestic substitution, expanding alternative markets, and deepening ties with partners willing to stay outside the restrictions. That response can be rational even if it is costly, because it reduces vulnerability.

3) Middle powers are trying to avoid being trapped.

Many countries do not want to choose sides. They want security cooperation with one partner and trade with another. They want investment without political strings. This produces a new kind of nonalignment that is less ideological and more transactional.

This is where the diplomatic story becomes most consequential.

If the world becomes too fragmented, countries that depend on open markets suffer. Yet if the world becomes too permissive, countries fear coercion and dependency. The diplomatic balance is fragile.

A useful way to view the new diplomacy is to map the main instruments states use and the diplomatic effects they generate:

| Instrument | Intended Goal | Typical Diplomatic Effect | Common Risk |

| Export controls on sensitive tech | Prevent strategic leakage | Aligns “trusted” partners, isolates targets | Spurs retaliation and substitution |

| Investment screening (inbound and outbound) | Protect critical assets and know-how | Forces clearer bloc boundaries in tech | Chills benign investment too |

| Sanctions and secondary restrictions | Raise costs for adversaries | Expands coalition politics | Pushes targets toward alternatives |

| Industrial subsidies and local content | Secure domestic capacity | Creates “club” supply chains | Trade disputes and subsidy races |

| Critical minerals strategies | Secure access and processing | Deepens ties with resource states | Resource nationalism and instability |

The institutional layer matters too. The WTO was built for a world where trade disputes were commercial disagreements under shared rules. It is now operating in an environment where countries increasingly invoke security exceptions and where disputes are tied to strategic rivalry. That makes rules harder to enforce and bargaining harder to stabilize.

Meanwhile, the G20 monitoring shows a world with intensifying trade policy activity but also ongoing dialogue and negotiation. That is an important nuance: fragmentation is rising, but the system has not given up on coordination.

For developing economies, the diplomatic stakes are high. If they become sites of “friend-shored” manufacturing, they can gain jobs and investment. If they are excluded from technology ecosystems or face higher borrowing costs due to risk perceptions, they can fall further behind. The World Bank’s warning that a significant share of developing economies remains poorer than in 2019 underscores how little room there is for new shocks.

The most plausible near-term outcome is not a hard division into two autarkic blocs. It is a world of selective openness: open in consumer goods and many services, restricted in advanced tech, critical infrastructure, and strategic inputs. That kind of world can still trade heavily, but it trades with more political conditions attached.

What Comes Next: 2026 Milestones and Scenarios for the New Iron Curtain?

The key question is whether de-risking stabilizes into predictable “rules of restraint” or escalates into a cycle of retaliatory restrictions. 2026 looks like a hinge year because several milestones will test whether countries can manage fragmentation without tipping into economic conflict.

Milestones to watch in 2026

- WTO Ministerial Conference (MC14), March 26–29, 2026 (Cameroon).

This is a rare moment when the world’s trade ministers meet with the authority to set direction. In a fragmented era, the most important outcome may not be a grand liberalization deal. It may depend on whether members can agree on guardrails that keep disputes manageable and prevent security claims from hollowing out the system. - USMCA joint review, scheduled for July 2026.

This review process matters beyond North America. It is a test case for how a major trade bloc handles renewal and uncertainty. If the review becomes politicized or used to extract unrelated concessions, it will reinforce the global message that trade rules are contingent and strategic. If it stays technocratic and stable, it becomes a counterexample that proves modern trade agreements can survive political churn. - Europe’s expanding economic security agenda, including outbound investment reviews and tougher screening.

As Europe builds tools to match its economic scale with strategic intent, it could either reduce vulnerabilities in a controlled way or add to fragmentation if coordination becomes heavy-handed or inconsistent across member states. The direction of implementation, not the announcement, is what will shape business decisions. - Trade growth and investment confidence under higher uncertainty.

The WTO’s sharp slowdown forecast for 2026 trade growth is a warning signal. If actual 2026 data undershoot even that low forecast, governments will face stronger domestic pressure to protect jobs and subsidize industries, which can further accelerate the cycle.

Three plausible scenarios

Scenario A: Managed De-Risking (most stable)

Governments keep restrictions targeted to sensitive sectors and build clearer licensing rules. Firms adapt through diversification without abandoning global markets. Trade grows slowly but steadily. This scenario requires restraint and predictability, especially in export controls and sanctions.

Scenario B: Competitive Fragmentation (most likely)

States continue expanding security tools into broader economic areas. Subsidy races intensify. Firms face higher compliance costs and more duplicated capacity. Trade still occurs, but growth remains weak, and investment becomes more regionally segmented.

Scenario C: Escalatory Decoupling (highest risk)

A major geopolitical shock or a series of retaliatory measures pushes restrictions into consumer sectors, finance, or large-scale industrial supply chains. This scenario would likely produce sharper inflationary pressure, investment freezes, and deeper growth slowdowns, with the greatest harm falling on import-dependent and debt-stressed economies.

Why this matters now?

The “New Iron Curtain” is not only about who trades with whom. It is about what kind of globalization survives. If the world shifts from rules-based openness to power-based market access, smaller economies lose leverage, investment becomes less efficient, and innovation becomes more segmented.

The paradox is that de-risking is rational in a world where coercion is possible, but it can also produce the very insecurity it is meant to avoid if it becomes too broad, too unpredictable, or too politicized.

In 2026, the most important signal will be whether leaders can define boundaries:

- What is genuinely “national security,” and what is economic competition dressed up as security?

- Which sectors require redundancy, and which sectors still benefit from openness?

- How are disputes resolved when security claims collide with trade rules?

If those boundaries remain blurry, the default will be escalation. If they become clearer, the world may settle into a colder, slower, but still functioning form of globalization, where cooperation survives not by trust, but by careful design.