For the millions of people worldwide living with advanced dry AMD (specifically the geographic atrophy form), a major clinical trial has announced results that could mark a turning point. On October 20, 2025, a multi-centre study led by institutions across Europe and the U.S. published its findings: a tiny wireless micro-chip implant, combined with augmented-reality glasses, was able to restore significant reading vision in participants whose central sight had been lost. According to published results in the The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), the device – known as the PRIMA System – enabled about 84 % of treated patients to read letters, numbers or words again.

This comes after decades during which dry AMD — and especially geographic atrophy (the subset where photoreceptors die and central vision fades) — had no approved treatment to restore vision. Existing therapies could only slow progression, not enable regained vision.

Trial Design and Key Findings

Participants and Scope

The trial enrolled 38 patients who had advanced geographic atrophy due to dry AMD, across 17 hospital sites in five countries (including the United Kingdom, France, Italy and the Netherlands). Science Corporation+2New England Journal of Medicine+2 Of these, 32 completed the full 12-month follow-up and training regimen. According to the NEJM article, of the 32 who completed the year, 26 achieved a clinically meaningful improvement in visual acuity (defined as an improvement of ≥ 0.2 logMAR, which approximates at least ten letters gained on the standard ETDRS chart).

Restoration of Reading Vision

The results are remarkable: on average, patients improved by more than five lines on a standard letter-chart test. Importantly, 84 % of the participants regained the ability to read letters, numbers or words using the implanted eye.

Vision Preservation and Safety

Crucially, the trial found no significant decline in the remaining peripheral vision of the implanted eye, which is especially important given that peripheral vision typically remains in these patients. Science Corporation+1 While there were adverse events—26 serious adverse events among 19 participants—most occurred within the first two months after surgery and 81% resolved within two months.

How the PRIMA System Works

The Hardware

At the heart of the system is a sub-retinal wireless micro-chip measuring approximately 2 mm × 2 mm and only about 30 microns thick — roughly half the thickness of a human hair. It is implanted beneath the retina in the zone where photoreceptor cells have died.

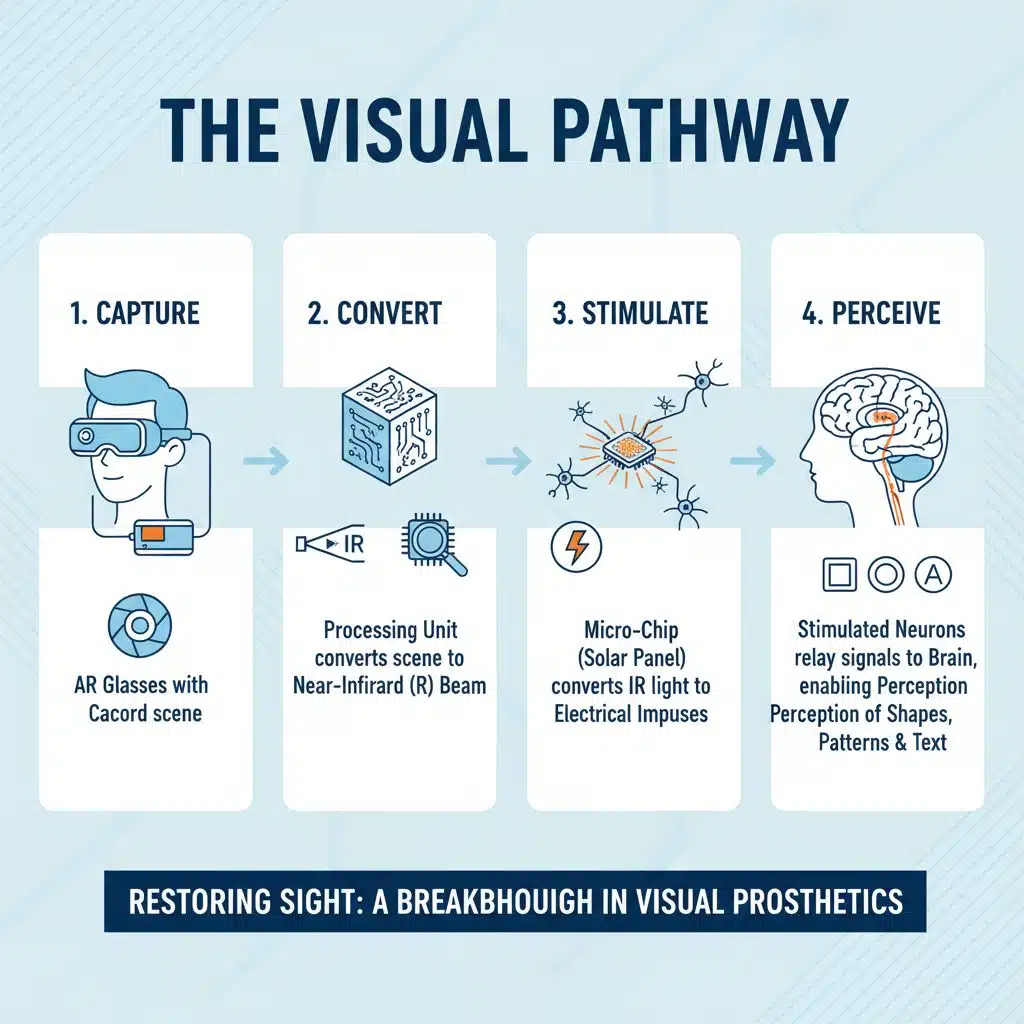

The Visual Pathway

Patients wear a pair of augmented-reality (AR) glasses equipped with a video camera. The camera captures what the patient would normally see, and a connected processing unit worn on the waist converts that scene into a near-infrared (IR) beam projected onto the micro-chip. The chip acts like a miniature “solar panel”: it converts the IR light into electrical impulses, which stimulate the remaining retinal neurons. Those neurons relay signals along the optic nerve to the brain, enabling the patient to perceive shapes, patterns and text.

Integration with Natural Vision

Since the implant is placed under the macular area where central vision was lost, and the patient’s peripheral retina remains intact, the system allows the patient to combine the newly prosthetic central reading vision with their natural remaining peripheral vision. This fusion enhances overall visual function, enabling tasks like reading, recognising objects and navigation in a way that purely peripheral vision alone cannot.

The Rehabilitation Process

One of the vital aspects of the trial is that successful vision restoration was not just surgical—it required extensive rehabilitation. Patients underwent months of training to learn how to interpret the new visual signals delivered by the implant. This training involved reading letters and numbers, practising visual scanning, zooming and focusing using the glasses, and integrating those signals with their brain’s interpretation of vision.

In the trial, following the implant and once the system was activated (typically after the eye had settled post-surgery), participants engaged in a structured training programme. By the end of one year, many were able to read lines of text and perform tasks previously impossible. The training emphasises that the device does not instantly restore vision; the brain must relearn how to interpret the signals the implant generates.

Limitations and Future Developments

Although the results are groundbreaking, the technology is not without current constraints:

-

The vision restored is currently black-and-white (grayscale); full-colour vision is not yet supported.

-

The chip currently contains 378 pixels at 100 micron width per pixel. Future versions under development aim for pixels as small as 20 microns and up to 10,000 pixels, which could deliver visual acuity near 20/80 or better, and with digital zoom possibly approach 20/20.

-

The trial targeted a specific subset: patients with late-stage geographic atrophy where photoreceptor loss is advanced but peripheral retina remains intact. It remains to be seen how the system will perform in other macular or retinal diseases.

-

Regulatory approval is still pending. The company developing the technology, Science Corporation, has submitted applications (CE mark in Europe) and the U.S. approval process is ongoing. Cost and availability (e.g., through national health systems) remain open questions.

Why This Matters

This trial represents the first time that a prosthetic device has restored functional central reading vision in patients whose only remaining vision was peripheral due to dry AMD’s geographic atrophy. Until now, treatments could only slow progression; no device had enabled reading again in this condition. With over 5 million people affected worldwide by geographic atrophy, the implications are profound.

Beyond the technology itself, the improvement in quality of life—ability to read books, medication labels, do crossword puzzles, boost independence and confidence—is equally significant. The trial helps shift focus from “managing blindness” to “restoring vision”.

What Happens Next

-

Regulatory Pathways: The next step is approval by regulatory bodies such as the European CE mark and the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA). Once approved, the device could become commercially available, though timelines and cost remain uncertain.

-

Next-generation Devices: Research is already underway on higher-resolution chips, colour vision support, more ergonomic glasses and faster rehabilitation protocols. These advances may broaden the eligible patient population and improve outcomes further.

-

Broader Applications: Because the implant works by stimulating intact retinal neurons rather than replacing photoreceptors directly, the technology has potential for other retinal degenerative conditions where photoreceptor loss is present but neuronal pathways remain. Future clinical trials may explore these expanded indications.

-

Access and Affordability: Ultimately, for the greatest benefit, the technology must be accessible and affordable. Discussions are underway about how health systems will adopt and reimburse such interventions, especially for conditions that currently have no effective treatment.

The PRIMA System trial offers real, tangible hope to a patient group who for decades faced progressive vision loss with no prospect of improvement. While challenges remain — from regulatory approval to cost, from training to broader applicability — the ability of 84 % of participants to read again is a milestone. This is not just a technological achievement—it is a human achievement: restoring independence, dignity and possibility.

For those affected by advanced dry AMD, what had once seemed inevitable darkness may now be a bridge back to light.