You felt it again, didn’t you?

That sudden jolt under your feet in Dhaka, Sylhet, or Chattogram. The cup on the table rattled. Your phone buzzed with messages: “Did you feel the earthquake?”

On 21 November 2025, a magnitude 5.5–5.7 earthquake hit near Ghorashal in Narsingdi, only about 25–40 km from Dhaka. At least 10 people died and more than 300–450 were injured – many not from building collapse, but from falling railings, broken walls, and panic as people jumped from buildings and rushed down staircases.

It was “only” a mid-5, yet it caused deaths. That’s the real warning.

In the last decade, seismic networks in and around Bangladesh have recorded hundreds of earthquakes, with dozens of magnitude 4+ events every year in the wider region. Many are small, but people feel the stronger ones more frequently now and keep asking:

“Why does Bangladesh keep shaking when we are not even right on a plate boundary like Nepal or Indonesia?”

Bangladesh sits in one of the most complicated and dangerous tectonic corners of the world.

Hidden faults, massive plate pressure, soft delta soil, and unplanned heavy buildings all combine to make even moderate earthquakes feel scary – and potentially deadly.

This article explains the full story in simple language:

- The real tectonic reasons

- The hidden faults under and around us

- The big historical quakes

- What 2025 research and official studies say about our future risk

- And, most importantly, what we can actually do about it

Why Does Bangladesh Get So Many Earthquakes?

Bangladesh sits on the Indian tectonic plate, but that plate is squeezed from three sides:

- The Himalayan collision in the north (India vs Eurasia)

- The Indo-Burma / Burma microplate pushing and subducting from the east

- A network of active, mostly hidden faults right under and around Bangladesh

These forces slowly bend and break the crust.

When the stored stress is suddenly released, the ground shakes – again and again.

The Real Tectonic Reason Behind Bangladesh’s Earthquakes

Look at a world tectonic map and you’ll see large plates moving like slow conveyor belts.

- The Indian plate is moving roughly 4–5 cm per year north–northeast, colliding with the Eurasian plate. That collision raised the Himalayas and still drives earthquakes in Nepal and India.

- To the east, the Indian plate is diving beneath the Burma / Indo-Burma block and the Sunda plate, along what geologists call the Indo-Burma megathrust.

Bangladesh sits right in this corner – pinched between the Eastern Himalaya to the north and the Indo-Burma ranges to the east.

Recent GPS (GNSS) studies show that:

- The Indo-Burma megathrust is locked and shortening at ~11.6 mm per year,

- And is capable of generating earthquakes larger than magnitude 8.2.

Think of Bangladesh as a delta squeezed in a tectonic vice.

The Three Main Forces

| Force Acting on Bangladesh | Direction | Approx. Speed | Result for Bangladesh |

| Indian Plate pushing towards Eurasia | North–Northeast | ~4–5 cm/year | Compresses and uplifts crust (Himalaya, Shillong Plateau) |

| India vs Burma / Indo-Burma block | East–West shortening | ~1–2 cm/year (part of 12–24 mm/yr India–Sunda motion) | Bends and breaks crust in northeast & southeast Bangladesh |

| Eurasian Plate to the north | Nearly fixed relative to India | – | Acts like a wall, building up stress |

This slow “three-way squeeze” makes the crust crack along faults, many of which are buried under sediments and not visible at the surface. That’s why Bangladesh feels tremors even though the nearest classic plate boundaries are hundreds of kilometres away.

Hidden Active Faults Inside and Around Bangladesh

Most people imagine the San Andreas Fault or big surface cracks when they hear “fault”. In Bangladesh, many dangerous faults are blind – they don’t break the ground surface in an obvious way.

Here are some of the key players, updated with recent research:

| Fault Name | Location | Approx. Length | Likely Capable Magnitude | Status |

| Dauki Fault | Along the southern edge of the Shillong Plateau, north of Sylhet | ~300–320 km | M 7.5–8.0 (great earthquakes) | Active |

| Madhupur Blind Fault | Hidden fault beneath Tangail–Mymensingh–west of Dhaka | ~100–150 km | Around M 6.9–7.1 in official scenarios | Active |

| Indo-Burma / Plate Boundary Fault system | Chattogram–Cox’s Bazar–Teknaf–Myanmar border | 100s of km as a system | M 7.5–8.5+ (part of megathrust capable of >8.2) | Locked & active |

| Submarine faults in northern Bay of Bengal | Offshore, between Bangladesh coast and Arakan/Andaman trench | Poorly mapped | Numerical models use M 8.0–8.5 scenarios with waves of several metres possible on parts of coast. | Tsunami-capable, under study |

Dauki Fault – The Giant to the North

Paleoseismology (trenching and dating of disturbed layers) along the Dauki Fault shows at least three great earthquakes in the last ~1,200 years:

- One between AD 840–920

- One around 1548

- And the 1897 Great Assam / Shillong earthquake (M ~8.0–8.1) on the central segment

If these events ruptured large parts of the Dauki system, the recurrence interval is roughly 350–700 years. We are now only about 128 years past 1897 – somewhere inside that long window, not safe beyond it.

All major studies agree on one thing:

The Dauki Fault is still active and still dangerous.

Madhupur Blind Fault – The Threat Beside Dhaka

The Madhupur Fault doesn’t show a spectacular surface break, but hazard models treat a M 6.9–7.1 event on this fault near Tangail as one of the most dangerous scenarios for Dhaka.RAJUK’s Urban Resilience Project and related studies estimate that such an earthquake could collapse a huge share of Dhaka’s buildings (we’ll come to that soon).

Historical Major Earthquakes That Shook Bangladesh

Bangladesh has centuries of strong shaking on record. Here is an updated overview focusing on events that strongly affected present-day Bangladesh:

| Year | Name / Region | Approx. Magnitude | Impact on (today’s) Bangladesh |

| 1548 | Bengal / Sylhet earthquake | ~7.5–8.0 | Major damage in Sylhet region, likely on the Dauki system. |

| 1762 | Arakan earthquake | ~8.5–8.8 | Heavy damage and subsidence near Chattogram coast; uplift and subsidence along Teknaf–St. Martin’s; a local tsunami occurred, but how large it was on the Bangladesh coast is still debated. |

| 1869 | Cachar (Silchar) earthquake | ~7.0–7.5 | Strong shaking in Sylhet and northeast Bangladesh. |

| 1885 | Bengal earthquake | ~7.0 | Cracks and damage in parts of Dhaka and the Ganges basin. |

| 1897 | Great Assam / Shillong Plateau | 8.0–8.1 | Massive damage in Meghalaya and Assam; strong effects in northern Bangladesh; associated with movement on the Dauki system and nearby faults. |

| 1918 | Srimangal earthquake | 7.6 | Serious damage in Srimangal–Sylhet; one of the strongest instrumentally recorded events affecting present-day Bangladesh. |

| Recent decades | Multiple regional quakes (Myanmar, northeast India, Bay of Bengal) | 6.0–7.7 | Many felt strongly in Bangladesh, including the 2021 Myanmar Hakha quake (M6.2) and the 2025 Myanmar M7.7 event that devastated towns in central Myanmar. |

| 2025 (21 Nov) | Narsingdi / central Bangladesh | 5.5–5.7 | Shallow quake ~25–40 km from Dhaka; at least 10 dead and 300–450 injured, from falling railings, walls, and panic. |

Notice something important:

We have not had a truly great (M8+) event directly affecting Bangladesh in the last century – but the faults that can produce them are very much alive.

Why People Feel “More Earthquakes” Now (Especially 2020–2025)

Older people often say: “We never felt so many quakes when we were young.”

They are partly right – but the full story has two parts.

1. Better Instruments, Faster Information

Since the mid-2010s, Bangladesh’s seismic monitoring has improved a lot:

- Dhaka University Earth Observatory runs a network of permanent seismic stations and GPS sites.

- Collaborative arrays like BIMA and TREMBLE deploy dozens of seismometers across Bangladesh and Myanmar.

- BMD operates the national seismic monitoring and provides public bulletins.

Result: Quakes that would have quietly passed 30 years ago are now recorded, mapped, and shared on phones within minutes.

2. Real Regional Activity & Clustering

Global and regional catalogs (e.g., VolcanoDiscovery, EarthquakeTrack, EarthquakeList) show:

- Hundreds of earthquakes in and near Bangladesh every year,

- And dozens of M4+ events annually within a few hundred kilometres of the country.

Many of the recent felt earthquakes are linked to:

- The Indo-Burma subduction system,

- The Himalayan / Shillong region, and

- Local and regional faults around Sylhet, Chattogram, and the Bay of Bengal.

Large earthquakes like the 2004 Sumatra (M9.1) and 2015 Nepal (M7.8) events did change the stress field across South and Southeast Asia, and some scientists study how this may influence future quakes on the Indo-Burma and Dauki systems. But this is still an active research area, not a precise forecast.

What About Groundwater Pumping in Dhaka?

In some countries, intense groundwater extraction has contributed to small or moderate “induced” earthquakes. For Dhaka:

- There is clear evidence of land subsidence and uneven ground from over-pumping.

- But there is no strong local proof yet that pumping is directly triggering felt earthquakes.

What is certain: subsiding, weakened ground makes buildings more vulnerable when shaking does arrive.

Why Earthquakes Are a Serious Concern in Bangladesh

Bangladesh’s Earthquake Risk in One Glance

Bangladesh is not just “occasionally shaky” – it sits in one of the most complex and active tectonic zones on Earth, with:

- Active plate boundaries to the north and east

- Very soft delta sediments that amplify shaking

- Extreme population density in cities like Dhaka

- Millions of buildings that were not designed with modern earthquake codes in mind

Recent events, like the magnitude 5.5–5.7 earthquake near Narsingdi on 21 November 2025 that killed at least 8 people and injured hundreds in and around Dhaka, show how even a mid-size quake can cause deaths, panic and building damage in this environment.

Global risk assessments now rank Dhaka among the top 20 most earthquake-vulnerable cities in the world, largely because of its combination of hazard, population and weak construction.

1. Geographical Location: Sitting on a Tectonic Crossroads

Bangladesh lies at the eastern edge of the India–Eurasia collision zone, exactly where several tectonic blocks interact:

- Indian plate pushing north and northeast into the Eurasian plate (building the Himalayas and Shillong Plateau)

- The Burma (Myanmar) microplate wedged between India and the Sunda plate, forming the Indo-Burma arc to the east

- The whole region overlain by the Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna (GBM) delta, with up to 15–20 km of sediment piled on top of active faults

In simple terms:

Bangladesh is squeezed between colliding plates to the north and a subduction zone to the east.

Key points:

- Bangladesh lies near the junction of the Indian, Eurasian and Burma plates, making it a seismically active fold-and-thrust belt with both crustal and subduction-related earthquakes.

- The Indo-Burma megathrust (east of Chattogram and Cox’s Bazar) has generated large quakes before (including the 2004 Sumatra-Andaman event further south) and is capable of magnitude 8+ earthquakes.

Seismic hazard maps and risk atlases for Dhaka and Bangladesh reflect this: they show multiple seismic source zones – to the north (Dauki–Shillong), east (Indo-Burma arc) and within the delta itself – all capable of producing strong shaking in Bangladesh’s major cities.

2. Expansion of Cities: More People and Concrete in Harm’s Way

Urbanisation in Bangladesh has exploded, especially in Dhaka, Chattogram and Sylhet:

- Dhaka’s metropolitan population is now around 21–22.5 million people, making it one of the world’s largest and fastest-growing megacities.

- Unplanned or loosely regulated urban growth has filled lowlands, canals and old river channels with new housing and high-rises.

Why this worsens earthquake risk:

- Many buildings have been built very quickly and cheaply, with limited geotechnical investigation or code-compliant structural design.

- Studies and media reports note widespread non-engineered or poorly enforced construction, and tragedies like the Rana Plaza collapse (over 1,100 dead) showed how dangerous weak reinforced-concrete frames can be.

- These new urban areas often rest on young, loose, water-saturated soils that can amplify shaking and are susceptible to liquefaction (more on that below).

So as cities expand horizontally onto soft ground and vertically with mid- and high-rise buildings, more people and assets are concentrated in zones that will shake the hardest during an earthquake.

3. High Population Density: When a Shaking City Is Packed with People

Bangladesh is one of the most densely populated countries in the world, and Dhaka is among the densest large cities on Earth:

- Dhaka city’s density is commonly estimated around 23,000+ people per square kilometre, with some sources giving over 47,000/km² depending on how the “city” boundary is drawn.

- The Dhaka metropolitan area hosts over 21–22 million people, and Bangladesh’s 2022 census counts about 165 million people nationwide, many of them living on the GBM delta.

Compare that with some other earthquake-prone cities:

- Manila: ~42,800 people/km² (city proper) – the world’s densest major city

- Tokyo metro area: around 6,200–6,300 people/km²

- Mexico City: ~6,000 people/km² in the city

Dhaka’s core density is several times higher than Tokyo or Mexico City, and in the same league as Manila. That means:

- In a strong earthquake, far more people are exposed per square kilometre.

- Narrow streets and dense building clusters make evacuation, fire-fighting and rescue much harder.

- Poorly constructed buildings in crowded neighbourhoods can trigger “domino” collapse patterns, turning one failure into many.

High density in the wider Ganges–Brahmaputra basin also means millions are at risk from secondary hazards like embankment failure, flooding and landslides triggered by earthquakes.

4. Soft Soils and Liquefaction: The Hidden Amplifier

Most of Bangladesh – including Dhaka – sits on the Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna delta, the world’s largest delta system, made of very thick, young, unconsolidated sediments.

This creates two major problems in an earthquake:

4.1 Site Amplification

- Seismic waves slow down in soft clay and sand but grow in amplitude, making shaking stronger and longer than on hard rock.

- Studies of Dhaka’s deep, soft deposits show significant potential for ground motion amplification, especially in the 1–2 second period range that is dangerous for mid-rise buildings.

This is similar to what happened in Mexico City in 1985, where buildings 300–400 km from the epicentre collapsed because they sat on old lake-bed sediments that super-amplified the shaking.

4.2 Liquefaction

When strong shaking hits loose, water-saturated sand, the soil can temporarily behave like a liquid – this is liquefaction:

- Buildings can tilt, sink or topple

- Roads, embankments and bridge approaches can crack or slide

- Underground pipes and tanks can float or rupture

Recent research has produced liquefaction hazard maps for Dhaka and the Dhaka Metropolitan Development Plan (DMDP) area, showing that many neighbourhoods – especially reclaimed land and low-lying filled areas – have moderate to high liquefaction potential in a scenario earthquake.

Given that:

- 80% of Bangladesh is essentially river delta and floodplain, with deep soft clays and silts, and

- Rapid development is filling ponds, swamps and old channels for housing and industry,

the combined effect is that even a moderate earthquake can behave like a much bigger one in terms of damage.

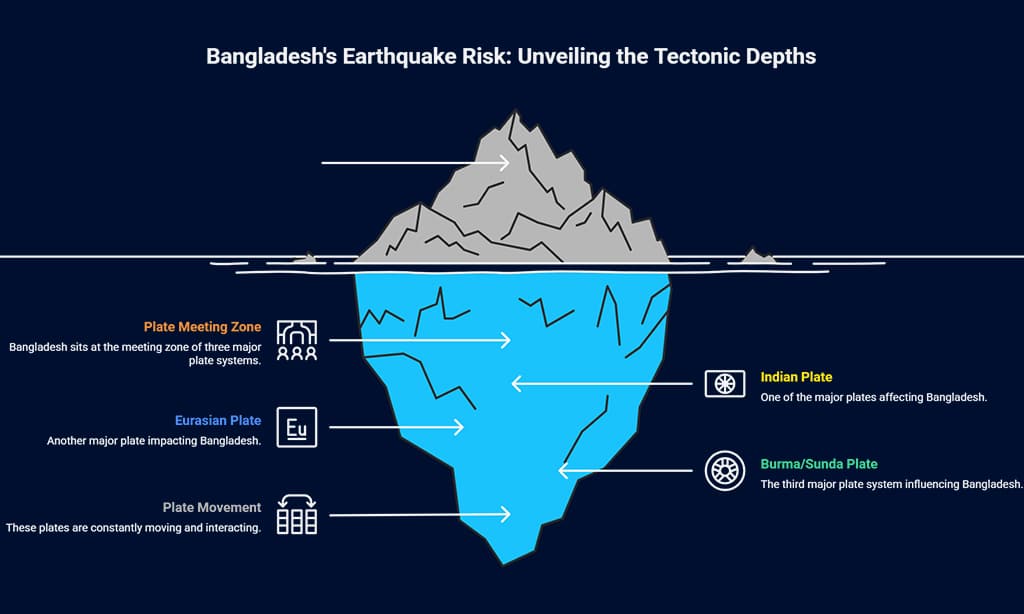

Tectonic Plate Setting of Bangladesh (Indo–Bangladesh Region)

To really understand why Bangladesh faces such serious earthquake risk, we need to look at how the tectonic plates interact around the Indo–Bangladesh region.

Bangladesh sits at the meeting zone of three major plate systems:

- The Indian Plate

- The Eurasian Plate

- The Burma (Indo-Burma) / Sunda Plate system

These plates are not static – they are slowly but constantly moving, pushing, colliding and sliding past each other. Bangladesh is caught in the middle of this slow-motion crush.

1. Indian Plate: The Driving Engine from the South

The Indian Plate is moving roughly north–northeast at about 4–5 cm per year relative to Eurasia. Over tens of millions of years, this movement has:

- Collided with the Eurasian Plate, building the Himalayas and Tibetan Plateau.

- Uplifted the Shillong Plateau in northeast India, just north of Sylhet.

For Bangladesh, this has two direct consequences:

- Himalaya–Shillong Collision Zone (to the north of Bangladesh)

- The Indian Plate is still pushing into Eurasia, creating a broad collision zone that includes:

- The Main Himalayan Thrust (source of quakes in Nepal and northern India)

- The Shillong Plateau area (source of the 1897 Great Assam earthquake)

- The southern margin of this uplifted block is defined by structures like the Dauki Fault, which runs roughly east–west along the northern edge of Sylhet.

- The Indian Plate is still pushing into Eurasia, creating a broad collision zone that includes:

- Stress Transfer Towards Bangladesh

- Although the main Himalayan front is north of Bangladesh, the shortening and bending of India’s crust spreads southward.

- This makes northern and northeastern Bangladesh (Sylhet, Mymensingh, Rangpur region) part of a deforming foreland, not a rigid, safe block.

2. Eurasian Plate: The “Wall” to the North

The Eurasian Plate lies to the north of the Himalayas and Tibetan Plateau.

From Bangladesh’s perspective, Eurasia is like a massive, relatively rigid wall:

- The Indian Plate can’t simply slide smoothly past it; instead it crumples and thickens at the boundary.

- That crumpling shows up as:

- The Himalayan mountain belt

- High seismicity along the Himalayan arc (Nepal, northern India, Bhutan)

- Uplift and faulting on the Shillong Plateau and surrounding regions

Because Eurasia is effectively “blocking” India, the stress has to be accommodated somewhere – and part of that “somewhere” is the northern margin of Bangladesh, including the Dauki system and adjacent faults.

3. Burma (Indo–Burma) and Sunda Plates: The Subduction Zone to the East

To the east of Bangladesh lies a very different tectonic environment:

the Indo–Burma (Myanmar) subduction and collision zone, which links into the Sunda Plate further southeast.

Here’s what’s happening:

- Indian Plate vs Burma/Sunda Block

- The Indian Plate, as it continues moving northeast, dives beneath or is forced under the Burma microplate and the Sunda Plate along a major megathrust fault system.

- This forms the Arakan Yoma / Indo–Burma ranges and offshore trench/foredeep structures in the Bay of Bengal.

- Locked Megathrust with Big Earthquake Potential

- Geodetic (GPS) studies show that part of this Indo–Burma megathrust is locked, meaning the plates are stuck together and strain is building up.

- This locked segment is believed to be capable of large (M 7.5–8.5+) earthquakes, which could:

- Devastate parts of Myanmar and northeast India

- Produce strong shaking in southeast Bangladesh, especially Chattogram, Cox’s Bazar, and the hill tracts

- In some scenarios, generate tsunami waves in the Bay of Bengal

- Upper-Plate Faulting into Bangladesh

- Above the megathrust, there are many folds and thrust faults in the Indo–Burma accretionary wedge.

- Some of these structures extend towards or into southeastern Bangladesh, influencing seismic hazard in:

- Chattogram and Cox’s Bazar region

- The Chattogram Hill Tracts

- Offshore gas and infrastructure areas in the Bay of Bengal

So while the north of Bangladesh feels the effects of the Himalaya–Shillong collision, the east and southeast feel the influence of the India–Burma/Sunda subduction system.

4. Bangladesh’s Crust: A Deforming Foreland Basin, Not a Solid Block

Underneath the rivers and cities, Bangladesh is not a single rigid chunk of rock. It is a thick foreland basin filled with kilometres of sediments on top of flexing, deforming crust.

Key points:

- The Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna (GBM) basin contains up to 15–20 km of sediment in places.

- The basement rock (the solid crust below the sediments) is being slowly bent and broken by the loading of sediments and the compression from the plate interactions.

- This setting allows for:

- Blind faults like the Madhupur Fault under central Bangladesh

- Reactivation of old basement faults, which can generate moderate to strong earthquakes even far from visible mountain belts.

That means Bangladesh is not like the stable interior of a continent (for example, central Australia or the Canadian shield).

It is a tectonically active, flexed and faulted basin at the edge of a major plate collision zone.

5. Indo–Bangladesh: How the Two Sides Interact

If you zoom out to the Indo–Bangladesh region, you see a continuous tectonic story:

- In India:

- The Indian Plate is colliding with Eurasia (Himalaya, Shillong, northeast India)

- It is also subducting under the Burma/Sunda system (Indo–Burma arc)

- In Bangladesh:

- The northern margin (Sylhet, Mymensingh) feels the stress from the Himalaya–Shillong–Dauki system.

- The eastern margin (Chattogram, Cox’s Bazar) is affected by India–Burma subduction and folding.

- The centre (Dhaka and the deep GBM basin) sits on thick sediments over deforming crust with hidden faults like Madhupur.

In other words:

Bangladesh is the downstream victim of India’s collision with Eurasia and its subduction beneath Burma/Sunda.

It absorbs stress from both directions – north and east – while sitting on a soft, over-thickened delta.

This combination is what makes Indo–Bangladesh such a critical seismic region:

India’s plate motion, plus Bangladesh’s soft, sediment-filled basin, plus the Burma/Sunda subduction, together create a complex and high-risk earthquake environment.

Bangladesh vs Nepal and India – Who Is at Higher Risk?

Many people think Nepal is more dangerous because of the 2015 Gorkha earthquake, which killed about 9,000 people and damaged over 600,000 buildings.

But if a similar-sized quake happened near Bangladesh, Dhaka could suffer equal or worse damage.

Important correction:

- Kathmandu is not on rock. The Kathmandu Valley is filled with up to 500 m of soft lake and river sediments, which strongly amplified shaking and caused liquefaction in 2015.

- Dhaka also sits on thick delta sediments, especially in many newly built areas.

So both cities have dangerous soft ground. But Dhaka has additional problems:

- Extreme population density – around 45,000 people per sq km in some areas, higher than Kathmandu and Delhi.

- Huge number of mid-rise, poorly detailed brick–concrete buildings, especially in old Dhaka.

- Chaotic utilities (gas lines, wires) that can turn a collapse zone into a fire zone.

International and local studies – including a Stanford-linked global index and Bangladesh government assessments – place Dhaka among the world’s most earthquake-vulnerable cities.

Updated Comparison (Conceptual)

| City | Population Density (approx.) | Dominant Ground in City Core | Shaking Amplification | Key Weakness |

| Dhaka | ~45,000 per sq km | Soft delta clay & sand | Can be 5–10× rock in some areas | Weak mid-rise buildings, poor code enforcement |

| Kathmandu | ~20,000 per sq km | Thick basin sediments (old lake) | Strong amplification (2–5×) | Many old masonry buildings |

| Delhi | ~11,000 per sq km | Mixed (rock + alluvium) | Moderate amplification (3–5×) | Very large exposed population |

So the right message is:

Nepal taught us how bad a big Himalayan earthquake can be. Dhaka’s combination of soft soil, extreme density, and weak buildings could make the disaster even worse here.

The Unique Threat in Bangladesh – Soil Amplification & Liquefaction

The Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna delta is built mainly from soft mud, clay, and sand delivered by the rivers. When seismic waves pass through these sediments, they:

- Slow down,

- But grow taller (higher amplitude), just like sea waves grow taller when they reach shallow water.

This is called site amplification.

A famous example is the 1985 Mexico City earthquake (M8.0). The epicentre was about 400 km away, yet buildings in the city collapsed because they sat on old lake-bed sediments that amplified the shaking dramatically. Dhaka, built on delta sediments, is worryingly similar in that sense.

Liquefaction – When Solid Ground Behaves Like Liquid

During strong shaking, water-saturated sand can lose its strength and behave like a liquid. This is liquefaction – it causes:

- Buildings to tilt or sink,

- Roads to crack and buckle,

- Buried pipes to float up or break.

Microzonation and site-response studies in Dhaka and other cities confirm that many areas built on reclaimed land, old channels, and loose sand are at high risk of amplification and liquefaction.

| Area | Liquefaction / Amplification Risk | Main Reason |

| Old Dhaka | Very High | Filled-up ponds, old river channels, very soft soil |

| Mirpur, Uttara, parts of Bashundhara | High | Sandy, reclaimed or filled soils with high groundwater |

| Chattogram Port area & coastal reclaimed land | Very High | Reclaimed land on soft marine sediments |

| Sylhet city floodplains | Moderate–High | Young river sediments, high water table |

Are We Prepared? BNBC-2020 vs Reality on the Ground

Bangladesh updated its National Building Code (BNBC-2020) with much better seismic provisions:

- The country is divided into four seismic zones with coefficients:

Z = 0.12 (Zone 1), 0.20 (Zone 2), 0.28 (Zone 3), 0.36 (Zone 4). - Dhaka lies in Zone 2 (moderate intensity, Z ≈ 0.20).

- Sylhet and Mymensingh lie in Zone 4 (very severe, Z ≈ 0.36) – the highest hazard zone in Bangladesh.

On paper, BNBC-2020 is a strong code, comparable in philosophy to modern international standards.

But the real picture is alarming:

- A RAJUK survey (around 1.95–2.4 lakh buildings in the capital region) found that about 66–67% of buildings violated building code provisions.

- Many structures lack proper column–beam joints, use low-strength concrete, skip soil tests, and ignore ductile detailing rules that allow buildings to sway without collapsing.

What If a Mid-7 Strikes Near Dhaka?

RAJUK’s Urban Resilience Project modelled a M6.9 earthquake on the Madhupur Fault near Tangail:

- 40–65% of Dhaka’s buildings (about 865,000 structures) could collapse or be unusable,

- Around 210,000 people may die and 229,000 may be injured if it strikes during daytime.

The State Minister for Disaster Management, Md Enamur Rahman, has publicly warned that:

A magnitude 7.0 earthquake could kill about 150,000 people in Dhaka and 500,000 across Bangladesh under current conditions.

So instead of “less than 10% follow the code,” it’s more accurate – and more powerful – to say:

About two-thirds of the buildings surveyed in Dhaka were built violating code, and official scenarios show hundreds of thousands of potential deaths in a major quake.

Expert Views & Probabilities – Will a Big Quake Hit Soon?

No scientist can say exactly when or where the next big earthquake will hit. But we can say:

- Paleoseismology shows the Dauki Fault has produced multiple M ~8-class earthquakes in the last 1,000+ years, with an average recurrence of about 350–700 years.

- GNSS shows the Indo-Burma megathrust is locked, shortening at ~11.6 ± 5.4 mm/year, and capable of Mw > 8.2.

- A new UNDRR–GEM earthquake risk model for Bangladesh (2023–2024) confirms high hazard levels, especially in the northeast and southeast, and identifies Dhaka, Sylhet, and Chattogram as critical risk hotspots.

In simple words:

Another large (M7.5+) earthquake in the region is geologically likely in the coming decades.

We cannot give a precise percentage or date – but we know the risk is real and increasing, not decreasing.

As Prof. A.S.M. Maksud Kamal and other Bangladeshi experts often stress: the important question is not “Will it happen tomorrow?”

It is “When it does happen, will our buildings and systems be ready?”

Tsunami Risk for Bangladesh – Real, But Not Like Japan

The 1762 Arakan earthquake did cause coastal uplift, subsidence, and local tsunami effects near Chattogram and along the Myanmar coast.

However, modern research suggests:

- The northern Bay of Bengal is less likely to produce a truly giant, ocean-wide tsunami like 2004 Sumatra,

- But scenario models with M 8.0–8.5 earthquakes along the Arakan–Andaman subduction zone still show several-metre-high waves possible on some parts of the Bangladesh coast.

The ThinkHazard platform classifies Cox’s Bazar tsunami hazard as “medium” – meaning more than a 10% chance of a potentially damaging tsunami in 50 years.

For coastal Bangladesh, that means:

- Tsunami risk is real but secondary compared with earthquake shaking itself,

- Coastal cities like Cox’s Bazar and Chattogram still need tsunami-aware planning and evacuation routes.

What Bangladesh Can Learn from Japan, Türkiye, Mexico – and Now Myanmar (2025)

Recent disasters worldwide have already shown us what to do – and what not to do.

1. Japan – Codes, Drills, and Early Warning

Japan invests heavily in:

- Very strict building codes,

- Regular nationwide drills,

- Earthquake early warning systems that can give even 10–20 seconds of alert before strong shaking arrives.

Even when very strong quakes happen, many modern buildings remain standing because they were designed to sway and dissipate energy.

2. Türkiye 2023 – What Happens When Codes Are Ignored

The February 2023 Türkiye–Syria earthquakes showed how deadly it is when:

- Buildings ignore codes,

- Old, weak structures are never retrofitted,

- And corruption allows unsafe construction.

Tens of thousands died, many inside “pancaked” buildings that had almost no ductile detailing.

Bangladesh has very similar construction styles in many mid-rise buildings. The key difference is: we still have time to fix them.

3. Mexico – Smart Use of Cheap Technology

Mexico uses:

- Low-cost seismic isolators and dampers in many schools and hospitals,

- A public siren-based early warning system in Mexico City.

Some of these ideas – especially basic isolators and neighbourhood-level alarms – can be adapted in Bangladesh for critical buildings.

4. Myanmar 2025 – A Regional Warning

In March 2025, a M7.7 earthquake in Myanmar destroyed towns and killed thousands. Dhaka felt smaller shocks from that event. It was a live demonstration that our region is truly capable of large, damaging earthquakes right now.

Simple Actions That Save Lives

You cannot stop the ground from shaking. But you can stop buildings and furniture from killing you.

For Families and Individuals

- “Drop, Cover, Hold On”

- Drop to your hands and knees

- Cover under a strong table or next to an interior wall

- Hold On until the shaking stops

- Stay away from stairs and elevators during strong shaking – many injuries in 2025 Narsingdi–Dhaka came from people running in panic.

- Tie tall cupboards, shelves, and TVs to walls.

- Keep heavy objects low and away from beds and sofas.

- Have a small “go-bag” with water, torch, basic medicine, and copies of key documents.

- Decide family meeting points and emergency contacts.

For Building Owners and Developers

- If you are planning a new building, demand a proper soil test and BNBC-2020 compliant design from a licensed engineer.

- For existing buildings, consider a rapid visual screening by an engineer trained in seismic assessment.

- Strengthen soft first floors (parking levels), add shear walls or bracing where possible.

- Fix obvious weaknesses: short columns, missing beams, unconfined brick infill, poor connections.

What the Government of Bangladesh Should Do Right Now

1. Make Unsafe Buildings a National Emergency

- Identify high-risk buildings in Dhaka, Chattogram, Sylhet, Gazipur (old, crowded, visibly weak).

- Start a time-bound programme to assess and retrofit:

- Schools

- Hospitals

- Fire stations

- Major bridges & flyovers

2. Enforce BNBC-2020 for Real

- No building permit without:

- Soil test report

- Structural design signed by a licensed engineer

- No occupancy certificate for big buildings without independent structural check.

- Fine, blacklist and publicly name developers who repeatedly violate the code.

3. Make Earthquake Drills as Common as Cyclone Warnings

- Declare a yearly “National Earthquake Drill Day” – schools, offices, factories all practice Drop, Cover, Hold On.

- Add simple earthquake safety to school textbooks.

- Use TV dramas, social media, mosque announcements to teach:

- Don’t run to stairs

- Protect head and neck

- Move calmly after shaking stops

4. Strengthen Early Warning & Anticipatory Action

- Roll out a unified alert system (same colours/symbols) for cyclone, flood, heat, storm.

- Scale up forecast-based cash support so poor families get help before a big flood/cyclone, not after.

5. Build Smarter Shelters, Not Just More

- Fill obvious shelter gaps in coastal and flood-prone areas using maps, not guesswork.

- Make new shelters:

- Multipurpose (school/clinic + shelter)

- Inclusive – separate toilets, ramps, lighting, space for women, elderly, disabled people.

6. Fix Urban Risk in City Plans

- Protect and recover drains, canals, and lowlands so cities don’t drown every monsoon.

- Keep emergency access roads clear in master plans (no building and no parking on them).

- Regular multi-agency drills (city + fire + health + army) for large urban disasters.

7. Put Real Money Behind DRR

- Set a minimum DRR budget every year (for safer buildings, shelters, early warning).

- Aggressively seek climate and resilience finance from international partners

- Publish simple public reports: which district got how much, and what was built or retrofitted.

Takeaways: 5 Key Takeaways You Should Remember

- Bangladesh is in a high-risk seismic corner – squeezed between the Himalaya and Indo-Burma, above active hidden faults like Dauki and Madhupur.

- Soft delta soil in Dhaka, Sylhet and coastal cities amplifies shaking and can liquefy, making even moderate quakes dangerous.

- Building vulnerability is our biggest problem. Studies show that 40–65% of buildings in Dhaka could collapse in a M6.9 scenario; about two-thirds of surveyed buildings violate code.

- A large earthquake (M7.5+) in the region is geologically likely within the coming decades, but we cannot predict the exact year or day. The 2025 Narsingdi quake was a small preview of how even moderate events can kill when buildings are weak and people panic.

- Earthquakes don’t kill people — weak buildings and lack of preparation do. Enforcing BNBC-2020, retrofitting key structures, and spreading simple safety habits can save tens or even hundreds of thousands of lives.

The ground will shake again.We cannot stop that.

But we can choose whether the next big earthquake becomes a national tragedy – or a test we survive with courage and preparation.