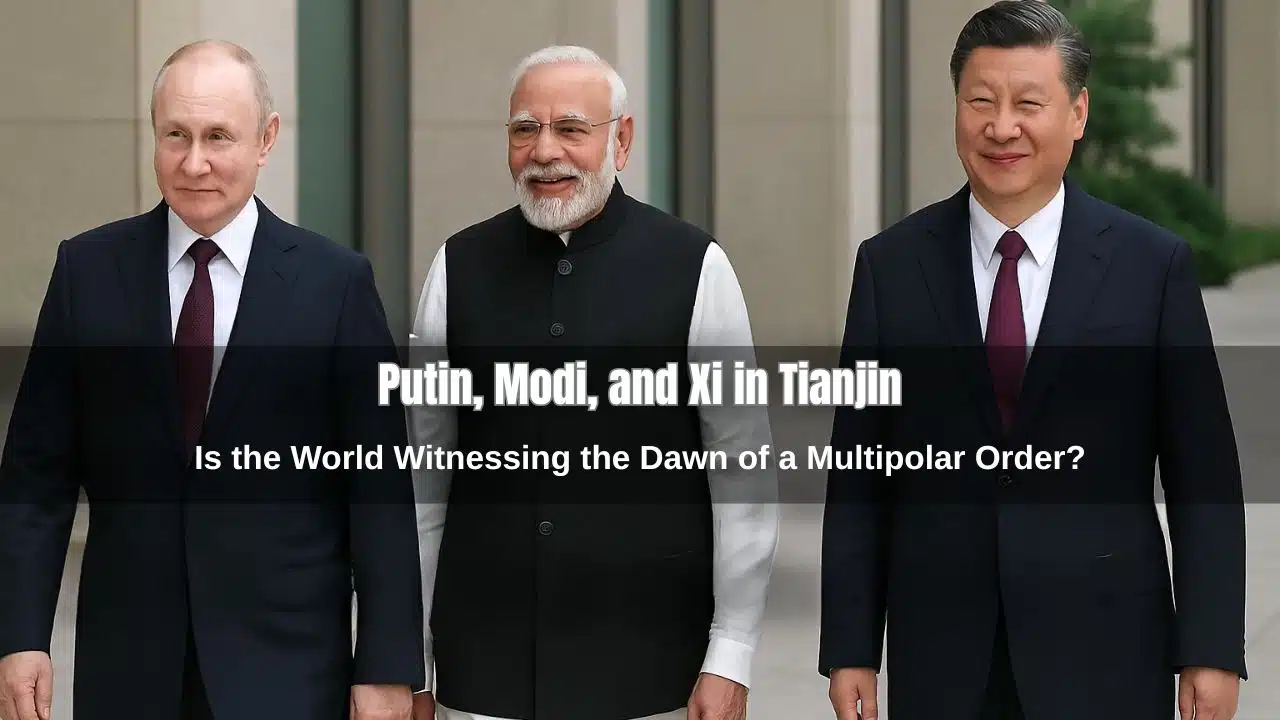

A single photograph can sometimes define a moment in history. At the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) Summit in Tianjin in early September 2025, one such image went viral: Russian President Vladimir Putin, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and Chinese President Xi Jinping walking together, smiling, and even laughing in unison.

To many in the West, it looked like a geopolitical alarm bell. To much of the Global South, it appeared as a symbolic assertion of sovereignty and balance.

This summit was not just another diplomatic gathering. It brought together the leaders of three major powers whose combined population, economies, and influence stretch across continents. The question that emerges is whether this moment in Tianjin signals the true dawn of a multipolar order—or if it is merely a symbolic gesture in a still unipolar world dominated by the United States.

The Context—Why Tianjin Matters

-

The Tianjin summit was more than another diplomatic gathering; it became a stage for three of the world’s most powerful leaders to project a shared vision of global politics.

-

By hosting the 25th SCO anniversary in Tianjin, China signaled its ambition to position the city—and the organization—as a counterweight to Western-led forums like NATO and the G7.

-

The image of Putin, Modi, and Xi together was not just a photo-op; it was a carefully choreographed symbol of solidarity that reverberated across world capitals.

-

For the Global South, Tianjin represented hope for a more balanced order, while in Washington and Brussels it raised concerns about the erosion of Western dominance.

-

The symbolism of Tianjin lies in its timing: at a moment of strained U.S.-China relations, ongoing Western sanctions on Russia, and India’s delicate balancing act, the summit amplified the call for multipolarity.

The SCO Summit as a Stage

The SCO has grown far beyond its original function as a security alliance among Central Asian states. With members now including India, Russia, China, Pakistan, and several others, it has become a platform where Eurasian and Asian powers test the waters of cooperation.

Tianjin’s summit was historic: the largest yet, featuring leaders not only from the core but also partner nations like Turkey. For China, hosting this gathering was a chance to showcase its diplomatic clout.

Symbolism of Unity

The photograph of Modi grasping Putin’s hand while Xi looked on with a rare smile resonated far beyond the conference halls. Western commentators immediately described it as a snapshot of a “new world order.” It is rare to see leaders who often disagree—especially India and China—standing side by side in a moment of visible camaraderie.

The symbolism was not lost on global audiences: the SCO is no longer a backroom club but a public stage for alternative visions of power.

The Multipolar Vision Taking Shape

-

The leaders in Tianjin stressed that the future should not be trapped in a Cold War binary but shaped by shared governance and sovereignty.

-

Xi’s proposal for an SCO Development Bank underscored the drive to build parallel institutions beyond Western financial control.

-

Multipolarity was framed not as confrontation with the West but as inclusivity—an order where Asia, Africa, and Latin America have a stronger voice.

-

The summit’s declarations reflected a common desire to dilute U.S. dominance and elevate regional partnerships.

-

For many in the Global South, the multipolar vision resonates as a corrective to decades of Western-centered globalization.

Rejecting Cold War Mindsets

Throughout the summit, leaders repeatedly emphasized that the world should not return to a Cold War binary. Instead of dividing into U.S. versus China blocs, the message was one of shared governance, respect for sovereignty, and a stronger role for the United Nations.

While critics argue this is rhetoric masking self-interest, the repeated rejection of “power rivalry” highlights a coordinated narrative aimed at winning legitimacy.

Building Parallel Institutions

Xi Jinping’s proposal for an SCO Development Bank grabbed headlines. The idea is to provide loans, credit, and financial infrastructure independent of Western-controlled institutions like the IMF and World Bank.

Coupled with BRICS’ discussions on alternative payment systems, it reveals a long-term ambition: building institutions that can reduce dependence on the dollar-dominated global economy.

Appeal to the Global South

For many in Africa, Latin America, and South Asia, the multipolar pitch resonates. These regions have long felt marginalized under Western-led financial and security frameworks. By presenting multipolarity as a corrective rather than a confrontation, the SCO leaders tapped into a growing sentiment: that global governance must reflect new realities of economic and demographic power.

India’s Balancing Act

India’s presence in Tianjin was perhaps the most complex. On one hand, it is a U.S. strategic partner through the Quad and major defense deals. On the other, its historic ties with Russia and geographical proximity to China compel engagement in Eurasian forums.

Recent U.S. tariffs on Indian goods have fueled suspicions that Washington may be taking New Delhi’s loyalty for granted, nudging Modi to diversify his options.

India’s Long-Term Interests

For India, the multipolar order is not about aligning fully with Moscow and Beijing—it is about maximizing autonomy. By engaging with both camps, Modi aims to elevate India as the voice of the Global South, securing energy access, economic resilience, and a leadership role in multilateral organizations. The Tianjin summit allowed him to publicly demonstrate that India will not be a junior partner in any bloc.

Russia and China’s Strategic Calculations

Russia and China approached Tianjin with different but converging goals. For Moscow, the summit was a stage to show it is not isolated despite Western sanctions, leaning on Asian partnerships to secure legitimacy and markets.

For Beijing, it was another step in building a multipolar narrative, using the SCO alongside BRICS and the Belt and Road Initiative to project leadership. Together, they framed their cooperation as a counterbalance to U.S. dominance, even if their interests are not always perfectly aligned.

Russia’s Pivot to the East

Russia’s war in Ukraine and subsequent Western sanctions have left Moscow heavily dependent on China and Asian markets. For Putin, the SCO summit was a vital platform to project relevance and to show that Russia is not isolated but part of an emerging coalition. The pivot eastward is no longer a choice but a survival strategy.

China’s Multipolar Narrative

For Xi, the summit reinforced his broader project of creating parallel institutions and narratives. By hosting Modi and Putin, China signaled that despite disputes, it can still convene and lead.

The SCO, along with the Belt and Road Initiative and BRICS+, is part of Beijing’s architecture of influence—designed to rival the U.S.-led order without directly mirroring it.

Western Alarm and Strategic Response

In Washington, the summit was viewed with unease. Former President Donald Trump bluntly claimed that “India and Russia appear lost to China’s orbit.” European capitals, already grappling with reduced leverage in Africa and the Middle East, see these developments as confirmation that Western dominance is no longer unquestioned.

The Multipolar Order as a Challenge

Western policymakers argue that multipolarity risks fragmenting global governance, undermining international law, and empowering authoritarian regimes. Supporters of Tianjin’s vision counter that the so-called “rules-based order” is selective and Western-centric. The clash of narratives itself illustrates how contested the concept of world order has become.

Takeaways

The Tianjin summit, with its iconic images and bold declarations, represents more than mere theater. It captures the aspiration of large parts of the world to escape U.S.-centric dominance and to shape a multipolar order that reflects their growing weight. Yet, the distance between aspiration and realization remains significant.

What we are witnessing is not the full dawn of multipolarity but the early glow of its morning light. For Western policymakers, dismissing it as symbolic would be shortsighted; for the SCO leaders, translating optics into action will be the real test. The Tianjin moment may not yet be the arrival of a new world order—but it certainly signals that the old one is fading.