South Korea is racing toward a future where money moves like software, but it does not want its currency to become a passenger on someone else’s rails. That is the political and economic tension sitting underneath the country’s fast moving digital asset agenda. At the center of it all is one question that sounds technical but cuts straight into state power: who gets to issue won denominated digital cash that people can use at internet speed.

That question is why the South Korea stablecoin law debate has become bigger than crypto. It is now a debate about sovereignty, banking power, cross border money flows, and whether private issuers can create money like instruments at scale without weakening the policy tools that governments rely on in a crisis.

In late 2025 and early 2026, the clearest theme in South Korea’s approach is this: policymakers increasingly want stablecoins to look and behave like regulated bank products, even if the tokens live on public blockchains. The policy direction points toward bank grade reserves, strict redemption rules, and stronger enforcement powers over suspicious activity. At the same time, the biggest comprehensive legislation remains delayed by a turf conflict between financial regulators and the central bank over who controls stablecoin issuance and oversight.

This article breaks down what South Korea is trying to build, why the fights are happening now, and what “stablecoin sovereignty” really means when a country tries to modernize payments without surrendering control of its currency.

Why Stablecoins Trigger Sovereignty Fears In The First Place

Stablecoins look simple on the surface. A user holds a token that stays near a fixed value, usually pegged to a fiat currency. The user can transfer it quickly, often at lower cost than traditional rails, and without waiting for bank hours. That sounds like a payments upgrade.

But stablecoins also create a parallel layer of money. If a stablecoin becomes widely used, it starts to behave like a deposit substitute. People can store value, pay merchants, and move funds across borders in a form that may not sit inside the traditional banking system. At that point, stablecoins stop being a crypto product and start becoming monetary infrastructure.

For a country like South Korea, the sovereignty concern has several dimensions.

First, a widely adopted private stablecoin can weaken monetary policy transmission. Central banks influence the economy by steering interest rates and the banking system’s liquidity. If a meaningful share of transactions and savings migrates into private tokens, central bank actions may not reach the same parts of the economy as effectively.

Second, stablecoins raise foreign exchange management questions. In open markets, stablecoins can accelerate capital movement and make it easier for funds to shift into foreign currency exposure. Even if a local currency stablecoin grows, it can still increase usage of dollar stablecoins through trading pairs, cross border settlements, and the broader crypto ecosystem.

Third, stablecoins compress time. In traditional finance, frictions slow things down. Settlements take time. Compliance checks take time. Banking windows exist. Stablecoins remove much of that friction. That is a feature for innovation, but a risk during panic. When people can redeem or move value instantly, runs can happen faster than legacy systems were designed to handle.

South Korea’s policymakers are responding to these risks by pulling stablecoins closer to the regulated banking perimeter.

What “New Banking Laws For Digital Assets” Means In Practice

South Korea’s regulatory discussion is often described in phases. One phase focuses on user protection and market integrity for trading, custody, and exchange conduct. A later phase expands into issuance, stablecoins, and broader market structure. The headline framing about “banking laws for digital assets” signals a deeper shift: policymakers want the parts of crypto that behave like money to be governed like money.

In practice, that approach usually implies four building blocks.

Bank-Grade Issuer Standards

A banking led stablecoin regime generally limits who can issue. Banks become the default candidates because they already operate under capital, liquidity, risk management, and supervision frameworks. Even if non banks participate later, they often have to meet bank like requirements.

This is where sovereignty enters. If banks issue won stablecoins, the state can lean on existing supervisory channels. It can also shape the structure of reserves, redemption mechanics, and reporting obligations with less friction than it would face with a sprawling set of lightly regulated issuers.

High Quality Reserves And Clear Redemption Rights

A stablecoin that aims to function as money must survive stress. That means robust reserves and predictable redemption.

A bank centered regime typically pushes for reserves held in cash, central bank reserves, or very short dated high quality government instruments, with strict rules on custody and segregation. It also requires clear redemption rights at par. In simple terms, users must be able to convert one unit of stablecoin into one unit of fiat in a reliable way.

This matters because stablecoin failures usually come from one of three weaknesses: poor asset quality, maturity mismatch, or unclear redemption pathways when panic arrives. Banking style rules aim to reduce those failure modes.

Tighter Controls On Illicit Flows And Market Abuse

As stablecoins integrate with exchanges and payment systems, authorities worry about money laundering, fraud, and manipulation. South Korea’s regulators have signaled a willingness to expand enforcement tools beyond traditional post event prosecution, including mechanisms that can freeze or suspend suspicious transactions earlier in an investigation.

This is a major philosophical shift. It treats crypto rails not as an untouchable frontier, but as financial plumbing that can be monitored, paused, and controlled when needed.

Integration With Existing User Protection Rules

South Korea already has a user protection baseline for virtual assets, including expectations around custody, safeguarding user funds, and tackling unfair trading. A stablecoin framework would likely sit on top of that foundation. That layered approach lets regulators claim continuity: first protect users in the market, then regulate issuance that resembles money creation.

The net effect is a “permissioned direction” even if the technology remains open. Tokens can run on public networks, but the issuance, reserves, and key gateways remain tightly supervised.

The Regulatory Turf War Driving The Delay

The most important political fact shaping the 2026 roadmap is not a single paragraph in a draft bill. It is the institutional conflict over who gets to lead stablecoin policy.

South Korea’s central bank, the Bank of Korea, has repeatedly signaled caution. It has argued for a gradual introduction of won denominated stablecoins, often framed as starting with tightly regulated banks and expanding later if the system proves stable. The central bank’s leadership has also raised foreign exchange concerns and warned that private issuance can complicate monetary and capital flow management.

On the other side, the Financial Services Commission and political actors who want a faster innovation cycle have shown interest in building a clearer legal framework for digital asset issuance, including stablecoins, potentially allowing broader participation under strict rules.

This is not merely a bureaucratic argument. It is a sovereignty argument about who controls the digital representation of the won.

Central banks see money as a public instrument. Financial regulators often see markets as a space where private actors can innovate, as long as rules control risks. Stablecoins blur the line between money and market product, so the two institutions naturally collide.

The collision has consequences. When stablecoin authority remains unresolved, comprehensive legislation stalls. That is why the broader digital asset framework has slipped, pushing key decisions into the 2026 legislative calendar.

The Bank Of Korea’s Cautious Logic: Stability First, Then Scale

To understand South Korea’s direction, you have to understand what the central bank fears most.

The Bank of Korea does not need stablecoins to run monetary policy, but it cannot ignore them if they become popular. If a won stablecoin becomes widely used, it becomes a new form of money like liability. The central bank then needs to ensure that this liability does not amplify systemic risk.

The BoK’s “gradual introduction” position reflects several concerns.

Monetary Policy Transmission

If people store value in stablecoins rather than bank deposits, changes in interest rates may have less influence on household behavior. Banks may also face different funding structures. That can change credit conditions.

Run Dynamics That Move At Internet Speed

Traditional runs require physical steps. People withdraw cash, move funds between banks, or queue for transfers. Stablecoin runs can occur within minutes. That speed can turn a localized rumor into a system wide problem.

Foreign Exchange And Capital Flow Sensitivity

A local stablecoin regime may reduce dependence on foreign tokens, but it can also increase crypto usage overall. That can lead to more onramps into dollar stablecoins, especially if global liquidity prefers dollar denominated instruments.

The BoK’s solution is to anchor issuance inside the regulated banking system first, where supervision is mature and the state has tested crisis tools.

The Market’s Push: Innovation Wants Clarity, Not Waiting

While central banks prefer caution, markets crave clarity.

South Korea has one of the most active retail digital asset communities in the world. Its fintech ecosystem is also mature, with large platforms that already operate at scale in payments, transfers, and consumer finance. For these firms, stablecoins look like a natural extension of what they do.

A stablecoin can simplify settlement, reduce payment fragmentation, and support cross border commerce. It can also power programmable finance features like automated escrow, conditional transfers, and real time merchant payouts.

The market’s core demand is not deregulation. It is predictable rules that allow product planning.

Some major fintech players have openly discussed preparing to issue won based stablecoins once the framework allows it. That posture alone increases pressure on lawmakers to resolve the authority dispute. If large platforms believe stablecoins will become a standard part of finance, they will lobby for a regime that lets them compete with banks, or at least participate under a license.

This is where the South Korea stablecoin law debate becomes a contest over industrial structure. If only banks can issue, banks gain a powerful new moat. If licensed non banks can issue under strict requirements, fintech platforms can compete, and stablecoins become part of a broader digital finance landscape.

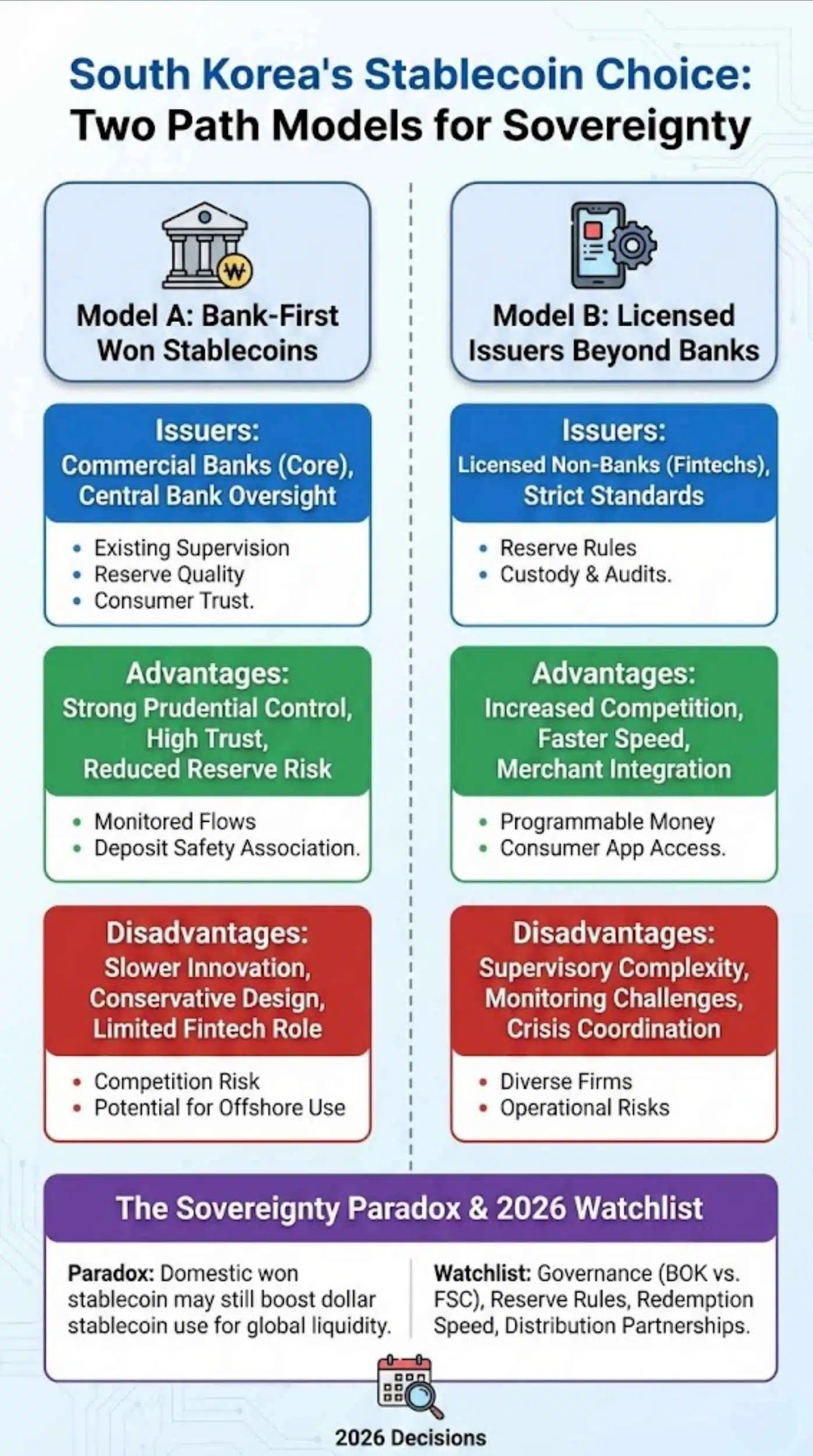

Two Competing Models South Korea Can Choose

South Korea’s stablecoin future will likely follow one of two models, or a hybrid. Your analysis becomes clearer when you treat these as distinct paths.

Model A: Bank-First Won Stablecoins

In this model, commercial banks issue won denominated stablecoins, possibly with the central bank shaping reserve standards and redemption requirements. Non banks may participate later through partnerships, distribution, or as licensed agents, but banks remain the core issuers.

This model offers clear advantages. It fits existing supervision. It reduces uncertainty about reserve quality. It supports consumer trust because people already associate banks with deposit safety, even if stablecoins are not legally deposits.

It also supports sovereignty. The state can monitor issuance and flows through institutions that already report deeply to regulators.

But there are costs. Innovation may slow. Product design may be conservative. Smaller fintech firms may lose the ability to compete. And if bank issuance becomes too restrictive or slow to roll out, users may continue using offshore or dollar stablecoins anyway, which weakens the sovereignty goal.

Model B: Licensed Issuers Beyond Banks Under Strict Rules

In this model, regulators create a licensing regime that allows non bank issuers, including fintech platforms, to issue won stablecoins if they meet strict standards for reserves, custody, governance, audits, and redemption.

This approach can boost competition and speed. Large platforms can integrate stablecoins into consumer apps quickly. Merchants can adopt stablecoin settlement in more places. Programmable money features can expand.

But it raises supervisory complexity. Authorities must monitor more issuers. They must ensure consistent reserve standards and robust operational controls across diverse firms. During a crisis, coordination becomes harder.

From a sovereignty lens, the state still controls the currency unit, but it must manage a larger ecosystem of private money issuers. That can feel uncomfortable for a central bank.

A hybrid approach could start with banks, then allow licensed non banks later once the first phase proves stable. That hybrid path aligns with the “gradual introduction” logic while still acknowledging market demand.

Why Enforcement Is Getting Tougher At The Same Time

One of the most important signals in South Korea’s 2026 posture is that authorities are not only debating stablecoin issuance. They are also strengthening enforcement tools around the broader virtual asset market.

Regulators have discussed mechanisms that resemble securities market controls, including the ability to suspend payments or freeze accounts linked to suspected manipulation or illicit flows at an earlier stage of an investigation.

For a news analysis, this matters because it changes the expected culture of the market.

A market where enforcement arrives months later encourages rapid cash outs and fast moving schemes. A market where accounts can freeze quickly discourages some abuse, but it also raises civil liberty and due process debates. If authorities can suspend transactions quickly, they need strong safeguards, clear thresholds, and transparent oversight to avoid overreach.

In the stablecoin context, stronger enforcement also has a strategic role. Stablecoins can make money movement faster, so regulators want faster intervention tools. The two policies reinforce each other. If the state allows money like tokens to scale, it will likely demand stronger control levers to manage abuse and panic.

How Won Stablecoins Could Reshape Banking And Payments

If South Korea successfully launches a regulated won stablecoin ecosystem, the consequences go far beyond crypto exchanges.

A New Settlement Layer For Fintech And Merchants

Stablecoins can settle instantly. That could reduce payment delays and chargeback complexity for certain merchant workflows. It could also enable real time payroll, instant refunds, and micropayments that feel clunky on card rails.

If stablecoins integrate into major consumer apps, users may not even think of it as crypto. They will experience it as faster money movement.

Pressure On Legacy Intermediaries

A stablecoin settlement layer can reduce reliance on some intermediaries in cross border commerce. It can also increase transparency in settlement flows, especially when combined with onchain reporting tools.

However, regulators will likely require permissioned checkpoints at onramps and offramps, including strict identity controls. That means intermediaries will not disappear. They will adapt.

Deposit Competition And Funding Questions

If consumers hold stablecoins as a store of value, banks may face deposit competition. Even if banks issue the stablecoins, the liability structure changes. Depending on legal design, a stablecoin may not behave like a traditional deposit.

Regulators will need to decide whether stablecoin balances receive any protections similar to deposit insurance, and how that affects consumer behavior during stress.

The Sovereignty Paradox: Even A Won Stablecoin Can Boost Dollar Stablecoins

A common assumption is that a domestic stablecoin automatically reduces reliance on foreign stablecoins. That can happen, but it is not guaranteed.

In crypto markets, many trading pairs and liquidity pools revolve around dollar stablecoins. Even if a won stablecoin becomes popular domestically, active traders may still move into dollar stablecoins for liquidity, global access, and cross border settlement.

This creates a paradox. By legitimizing stablecoins as a concept, a country can increase overall stablecoin usage, including foreign currency tokens, unless it builds incentives and infrastructure for the local unit.

South Korea’s sovereignty strategy therefore needs two layers.

First, it needs a safe won stablecoin framework that users trust.

Second, it needs an ecosystem that makes the won stablecoin useful beyond a narrow domestic niche. That means merchant acceptance, integration with major apps, and meaningful liquidity.

If it fails on that second layer, the won stablecoin may exist, but dollar stablecoins will remain dominant for certain uses, especially cross border and trading.

What To Watch In 2026: The Decisions That Will Define The Regime

As South Korea moves deeper into 2026, several decision points will reveal which model wins.

Who Controls Licensing And Supervision

The biggest issue remains governance. If the Bank of Korea gains a strong role in licensing or direct oversight, the system will skew toward bank-first issuance and conservative design. If the Financial Services Commission leads licensing, the regime may open more quickly to non bank issuers under strict rules.

A shared governance model is possible, but shared models can create slow decision making during crises unless responsibilities are very clear.

Reserve Composition And Custody Rules

Watch the reserve standards. If regulators require reserves in cash and near cash instruments with strict custody segregation, they signal a strong prudential stance. If they allow broader assets, they invite higher yield but also higher risk.

Redemption Speed And Consumer Rights

The redemption promise becomes the real product. If stablecoins promise rapid redemption at par with strong operational guarantees, they can compete with deposits as a store of value. If redemption is slow or constrained, stablecoins become a niche settlement tool rather than widely held money.

Distribution: Banks Alone Or Platform Partnerships

Even under a bank-first issuance model, distribution can shape outcomes. If banks issue but partner with large fintech apps to distribute stablecoins to millions of users, adoption can accelerate. If banks keep distribution limited, adoption may lag and users may stick with offshore options.

What This Means For The Rest Of Asia

South Korea’s approach matters beyond its borders because it sits at the crossroads of advanced consumer fintech adoption and strong regulatory institutions. Many countries in Asia face the same dilemma: they want faster payments and programmable finance, but they do not want private tokens to weaken capital controls or monetary authority.

If South Korea builds a bank-grade stablecoin regime that still achieves consumer scale, it becomes a template. If it builds a conservative regime that fails to attract users, it becomes a cautionary tale.

Either way, the policy lesson will travel. Neighboring markets will watch how Korea balances innovation, enforcement, and sovereignty.

Stablecoin Sovereignty Is About Power, Not Code

Stablecoins force governments to confront an uncomfortable reality. Payments innovation no longer requires rewriting the banking system from scratch. A private issuer can create a money like instrument and distribute it through an app with millions of users.

South Korea is responding with a strategy that tries to capture the benefits of digital rails without giving up control of the currency unit. That is why the debate keeps returning to banks, reserves, redemption, and enforcement.

The next year will likely decide whether South Korea builds a stablecoin regime that feels like modern banking onchain, or whether it allows a broader set of licensed issuers to compete under strict safeguards. Either way, the sovereignty lens will dominate the conversation. The South Korea stablecoin law will not just regulate tokens. It will define who gets to build the next layer of money.