Somalia’s turn holding the UN Security Council gavel in January 2026 comes as the Horn of Africa turns into a Red Sea security hotspot and as the Council strains under great-power rivalry. A state once treated mainly as a crisis file now gets to shape the agenda, even if briefly.

How We Got Here: From Sanctions Target To Agenda-Setter

Somalia’s presidency is not just a calendar quirk. It is a narrative reversal.

For three decades, “Somalia at the UN” largely meant emergency briefings, humanitarian appeals, counterterrorism updates, and sanctions compliance. The Security Council imposed an arms embargo in 1992, reflecting how the international system saw the Somali state: not as a co-author of rules, but as a place where rules had collapsed. That started to shift in the 2010s as Somalia rebuilt national institutions, re-engaged multilaterally, and leaned on a long arc of security assistance from the African Union and partners.

Two Council decisions mark the change in posture. First, the Council fully lifted the general arms embargo on the Somali government in December 2023, ending a restriction that had shaped Somali sovereignty for a generation. Second, the Council endorsed the transition from ATMIS to AUSSOM and set a clear end-date for UNTMIS operations in October 2026, placing Somalia’s security transition on a countdown clock.

Then comes the symbolic milestone: at a January 2, 2026 press conference, Somalia’s ambassador underscored it had been 54 years since Somalia last held the rotating presidency, framing the moment as a return, not a debut.

| Milestone | Why It Matters |

| 1992: UN arms embargo established | Internationalized Somalia’s security constraints and treated state weakness as a global risk. |

| Dec 2023: Arms embargo lifted for Somalia’s government | A sovereignty signal and a bet that Somali institutions can manage weapons accountability. |

| 2025–2026: Somalia serves as an elected Council member | Somalia shifts from “agenda item” to “agenda actor,” inside Council negotiations. |

| Jan 2026: Somalia holds the Council presidency | Somalia chooses debates, chairs meetings, and frames themes during a high-tension geopolitical month. |

| Oct 31, 2026: UNTMIS scheduled to cease operations | Raises the stakes on Somali self-reliance and donor follow-through in 2026. |

The point is not that Somalia suddenly “runs” the Council. It does not. The point is that Somalia can now influence how the Council talks, which issues get oxygen, and which coalitions form around language like sovereignty, territorial integrity, rule of law, and civilian protection.

What A One-Month Presidency Really Buys

The Security Council presidency is best understood as procedural power, not strategic dominance.

The president convenes meetings, steers the provisional agenda, shapes the month’s program of work, and can elevate “signature events” that set the rhetorical frame for later negotiations. In practice, presidencies matter most when they (1) force attention on neglected files, (2) create a concept note that becomes a reference point, and (3) convene briefers who change the temperature of debate.

Somalia is using that space deliberately. Its published program of work highlights a signature open debate on strengthening the rule of law, plus a quarterly Middle East debate that Somalia will chair. This is revealing: Somalia is choosing a theme that implicitly critiques a world where power politics often outruns legal constraints, while also placing itself as a “bridge-builder” between camps that increasingly speak past each other.

| Presidency Lever | How It Works In Practice | Why It Matters In 2026 | Hard Limit |

| Program of work | Sets the month’s rhythm and sequencing | Sequencing can raise pressure on stalled crises | Cannot force adoption of outcomes |

| Signature debates | Frames a theme and invites specific briefers | “Rule of law” pressures big powers without naming them | Debates can become talk shops |

| Chairing meetings | Controls pace, speakers list, and tone | Tone matters when Council unity is fragile | P5 still control veto and red lines |

| Narrative framing | Sets the “headline” language in concept notes | Helps elected members coordinate around shared terms | Language does not equal enforcement |

So the analytical question is not “What resolution will Somalia pass?” It is: What geopolitical story will Somalia tell from the Council’s most visible chair, and who will try to use that story for their own ends?

Somalia UN Security Council Presidency 2026 And The A3 Moment

Somalia’s presidency lands at a moment when African elected members have tried to act less like isolated voices and more like a coordinated bloc.

In 2026, the African “A3” caucus on the Council is Somalia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Liberia. That matters because Africa’s security agenda is not a niche docket. It is central to UN peace operations, sanctions, counterterrorism mandates, and the credibility of multilateral conflict management.

The A3 trend has been to push Council debates toward political solutions and African ownership, while also resisting what many African diplomats perceive as selective enforcement of international law. A rule-of-law signature debate chaired by Somalia fits that pattern.

But the A3 also faces a structural tension: the Council is where Africa seeks solidarity, yet Africa’s crises are also where big powers compete most intensely. In 2026, DRC sits on the Council while eastern Congo remains a top-tier international security concern, and Liberia brings post-conflict credibility and a strong interest in peacebuilding and institution-building. Somalia’s value-add is different: it sits at the junction of counterterrorism, maritime insecurity, and Red Sea geopolitics.

If the A3 acts cohesively, Somalia’s presidency can become a coordination engine: shared talking points, mutual support on drafting language, and a louder collective voice on principles like sovereignty and territorial integrity. If the A3 fractures, Somalia’s month becomes symbolic rather than strategic.

Horn Of Africa Fault Lines: Somaliland, Ethiopia, And Red Sea Politics

Somalia’s presidency is happening while its most sensitive sovereignty dispute has become newly internationalized.

In early January 2026, Reuters reported that Israel’s foreign minister visited Somaliland after Israel formally recognized Somaliland as independent, prompting strong condemnation from Somalia and wider backlash. This is not a local diplomatic spat. Somaliland sits on the Gulf of Aden across from Yemen, near one of the world’s most strategic maritime choke points. Any move that appears to legitimize territorial revision in the Horn of Africa lands directly on Security Council values like territorial integrity and non-recognition norms.

That makes Somalia’s Council gavel unusually relevant. Somalia cannot adjudicate recognition. But Somalia can force the Council to repeatedly confront the second-order consequences: escalation incentives, regional alignments, and how external powers may try to “rent” influence in the Horn through ports, basing, and security cooperation.

This also connects to the Ethiopia–Somaliland port-access dispute that flared in 2024 and required regional mediation to cool down. Many analysts have emphasized that the dispute is not only about commerce, but about sea access, naval presence, and status claims that can reorder alignments among Ethiopia, Somalia, Egypt, Turkey, and Gulf states.

A useful way to read Somalia’s rule-of-law framing is as a diplomatic shield: it lets Somalia argue that territorial integrity disputes must be managed by principle and process, not by unilateral recognition or security faits accomplis. That argument will resonate with many Global South states, even those that do not take Somalia’s side on every detail, because it protects them from similar precedents.

| Flashpoint In 2026 | Why It Became Hot Again | Who Is Involved | What The UN Can And Cannot Do |

| Somaliland recognition dynamics | Red Sea security competition and diplomatic signaling | Somalia, Somaliland, Israel, regional actors | UN can debate and shape norms; it cannot “grant” recognition |

| Ethiopia sea-access politics | Landlocked strategy and port leverage | Ethiopia, Somalia, Somaliland, mediators | UN can support de-escalation; regional diplomacy still does the heavy lifting |

| Red Sea conflict spillovers | Missile threats and rerouting increase stakes for ports | Yemen actors, naval coalitions, littoral states | UN can coordinate political pressure; maritime security depends on navies and insurers |

The forward-looking risk is miscalculation. A single diplomatic move can trigger retaliatory alignments: new arms flows, base negotiations, or proxy pressure in border areas. Somalia’s presidency gives Mogadishu a louder megaphone to discourage that spiral.

Maritime Security: Piracy Returns As Trade Routes Shift

If Somalia wants to show it is a “global” player, not just a regional case study, maritime security is the most credible lane.

The Red Sea crisis has pushed shipping routes into longer and riskier patterns. UNCTAD’s maritime reporting has documented steep drops in Suez and Gulf of Aden transits during the period when rerouting accelerated, alongside sharp increases in Cape of Good Hope traffic. Longer routes raise operating costs, insurance premiums, and exposure to attack windows.

At the same time, piracy indicators have worsened off Somalia. The ICC International Maritime Bureau’s January–June 2025 report recorded three vessel hijackings in waters off Somalia in the first half of 2025 and noted multiple piracy incidents in the Somalia–Gulf of Aden theatre in 2024. The strategic implication is bigger than piracy: Red Sea insecurity has become a global supply chain vulnerability, which means Somalia’s coastline is no longer treated as distant periphery.

Somalia’s comparative advantage is that it can speak with legitimacy on both halves of the problem:

- Onshore drivers: poverty, governance gaps, conflict financing

- Offshore reality: naval patrols, ship hardening standards, regional coordination

If Somalia uses its presidency to convene a serious discussion that links piracy, illicit finance, and insurgent adaptation, it can push the conversation beyond the usual cycle of alerts and patrol rotations. The Council has levers here through sanctions architecture, reporting requirements, and attention to regional maritime security cooperation, even if most operational capacity sits outside the UN.

Key Statistics To Watch

- Three hijackings off Somalia waters in the first half of 2025 (IMB).

- Multiple piracy incidents and hijacking events off Somalia and the Gulf of Aden in 2024 (IMB).

- Major route disruptions away from the Red Sea corridor during the height of rerouting (UNCTAD).

The Security Transition: AUSSOM, UNTMIS, And The Funding Gap

Somalia’s presidency happens while Somalia’s own security architecture faces a make-or-break year.

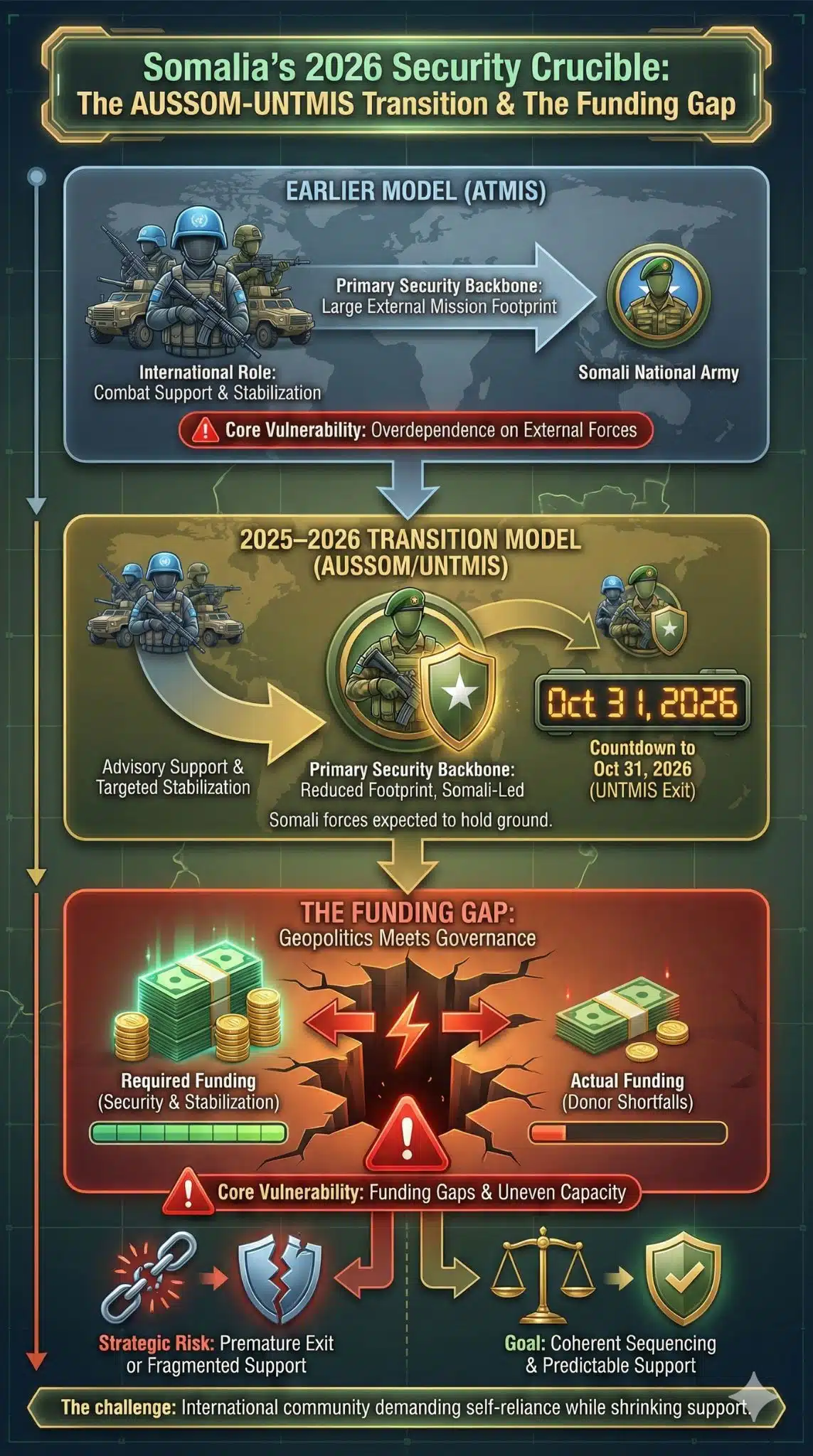

The Council’s endorsement of the transition from ATMIS to AUSSOM is intended to mark a shift toward Somali-led security responsibilities. More recently, UN coverage has emphasized that UNTMIS is scheduled to cease operations on 31 October 2026 after completing the second phase of its transition, creating a clear institutional deadline.

Deadlines matter because they expose whether “transition” is real or rhetorical. Somalia has gained capacity, but insurgent pressure remains intense, and financing remains the persistent constraint. IMF reporting has warned that security operations face constraints from funding gaps and reduced external support even as Somalia pursues macroeconomic reforms.

This is where geopolitics meets governance. Somalia’s presidency can highlight a principle many donors privately acknowledge: the international community cannot demand self-reliance while simultaneously shrinking predictable support for security and stabilization. That is not a plea for endless mission presence. It is an argument for coherent sequencing.

| Before Vs After: Somalia’s Security Support Model | Earlier Model | 2025–2026 Transition Model |

| Primary security backbone | Large external mission footprint | Reduced footprint with Somali forces expected to hold ground |

| International role | Combat support and stabilization | Advisory support plus targeted stabilization |

| Core vulnerability | Overdependence on external forces | Funding gaps and uneven Somali capacity |

| Strategic risk | Perpetual mission | Premature exit or fragmented support |

Somalia’s presidency also creates a reputational incentive: Mogadishu will want to project seriousness and competence while it chairs the world’s top security table. That can strengthen reformers, but it can also produce performative diplomacy if core political bargains inside Somalia remain unresolved.

Humanitarian Reality Meets Geopolitics

Somalia’s global profile rises at the same time humanitarian space tightens.

OCHA’s Somalia 2026 humanitarian planning documents put millions in need and describe a crisis that remains severe and protracted. The 2026 humanitarian approach also reflects “hyper-prioritization,” with a narrower target population than total needs, and a funding requirement measured in the hundreds of millions of dollars. Meanwhile, WFP has warned of major reductions to food assistance tied to funding shortfalls, including cuts that leave large numbers without support at a time when displacement and local insecurity remain persistent.

These realities matter for geopolitics because food insecurity and displacement feed instability, and instability creates openings for armed actors and criminal economies. When Somalia talks about rule of law at the Council, it is not abstract legalism. It is a claim that norms, protection, and accountability are downstream from whether people can eat, move safely, and trust institutions.

| Humanitarian And Economic Pressure Points | 2026-Linked Figure | Why It Matters Politically |

| People in need (Somalia) | 4.8 million | Strains legitimacy and worsens local conflict dynamics |

| People targeted for aid | 2.4 million | Triage can leave fragile districts exposed |

| Funding requirement | $850 million | Tests donor priorities amid multiple global crises |

| Macro outlook signals (IMF projections) | 2026 real GDP growth 3.0%; inflation 3.6% | Growth without stability can still leave conflict drivers intact |

The strategic lesson is uncomfortable: Somalia can gain diplomatic stature in New York while its people face a thinner safety net at home. That tension will shape how credible Somalia’s presidency feels to both supporters and skeptics.

Where Analysts Disagree

A serious analysis has to admit the two strongest counter-arguments.

First, many diplomats argue that the Council presidency is mostly ceremonial. The P5 can veto outcomes, and penholder dynamics often sit with major powers. On this view, Somalia’s month is symbolically important but operationally limited.

Second, some analysts warn that spotlight moments can backfire for fragile states. High visibility invites external bargaining, pressure campaigns, and domestic political grandstanding. A presidency does not immunize Somalia from internal fragmentation or regional coercion.

Both critiques are valid, but incomplete.

The presidency is not a magic wand. It is a multiplier. If Somalia already has diplomatic preparation, coalition partners, and a clear narrative, the presidency amplifies them. If Somalia lacks those, the month passes with little trace. Somalia’s choice of a rule-of-law signature debate signals strategic intent, not just symbolic pride.

The deeper dispute is about what “rule of law” means in 2026. For some Western states, it signals accountability mechanisms and civilian protection. For some non-Western states, it signals sovereignty, non-interference, and restraint by powerful militaries. Somalia is trying to occupy the center by insisting these principles belong together. Whether the Council accepts that synthesis will depend on the conflicts dominating the agenda that month, especially the Middle East file and wider accountability debates.

What Comes Next: Milestones And Scenarios For 2026

Somalia’s presidency will be judged less by speeches and more by what it sets in motion.

Milestones to watch

- Whether the January 2026 rule-of-law debate produces concrete follow-through rather than generic statements

- How Council discussions in 2026 handle Horn of Africa sovereignty disputes amid new recognition moves and security bargaining

- Whether maritime insecurity prompts tighter coordination across sanctions, illicit finance tracking, and naval cooperation if piracy indicators remain elevated

- Whether donors align security transition timelines with realistic financing as UNTMIS moves toward its October 31, 2026 end date

- Whether humanitarian triage hardens into a sustained “new normal” for Somalia, raising volatility in the most vulnerable districts

Agenda-Setting Success (More Likely If Coalitions Hold)

Analysts suggest Somalia can use January to lock in a rule-of-law framing that later elected members keep repeating, especially through the A3. That would not solve conflicts, but it can change negotiating gravity by making legal and civilian-protection language harder to ignore.

Sovereignty Shock (If Somaliland Dynamics Escalate)

If recognition politics trigger further escalatory steps, Somalia’s diplomacy could shift from bridge-building to defensive mobilization. That risks polarizing Council debate along geopolitical lines, reducing room for compromise.

Transition Stress Test (If Security Or Aid Financing Drops Further)

If security funding gaps widen and humanitarian cutbacks deepen, Somalia’s global standing can clash with domestic fragility. In this scenario, the presidency becomes a moment of prestige that fails to translate into resilience.

In all scenarios, Somalia’s presidency is a signal of where geopolitics is heading: more Global South states seeking not just seats at the table, but control of the microphone. That will not fix the Council’s structural problems, but it will change the language of legitimacy inside the world’s most important security chamber.

Final Thoughts

Somalia UN Security Council Presidency 2026 matters because it sits at the intersection of three forces that define this decade: a Security Council struggling for coherence, a Horn of Africa pulled into Red Sea power politics, and a fragile state trying to convert partial recovery into durable sovereignty. The month is short, but the precedents it sets on rule of law, territorial integrity, and maritime security can echo across 2026.