Salil Chowdhury’s music sounds gentle at first. The tunes are sweet. The orchestras are rich. The voices are soft and clear. But if you listen more closely, you hear something deeper. You hear hunger. You hear workers marching. You hear about farmers losing land. You hear a protest hidden inside the melody.

That is why Salil Chowdhury is special. He was not only a film composer. He was a Marxist writer, activist and cultural worker. His life shows what happens when melody meets Marxism. On every birth anniversary and especially around his centenary, music lovers, scholars and political activists still go back to his songs and films.

This article revisits his journey, his politics, his film work, his protest songs, and why his legacy matters in today’s India.

Who Was Salil Chowdhury? The Man Behind the Music

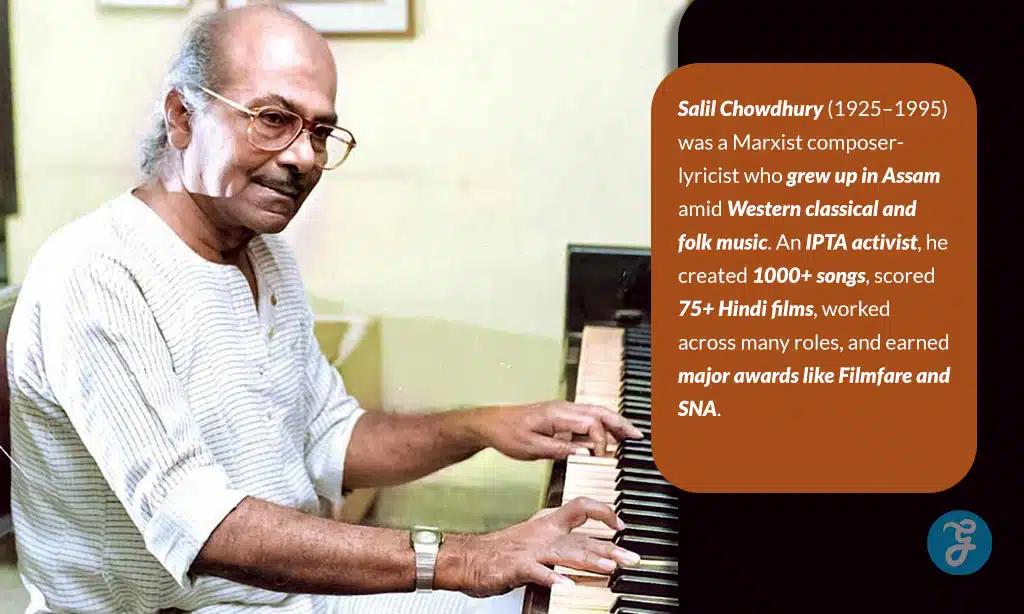

Most current references agree that Salil Chowdhury was born on 19 November 1925 in the village of Ghazipur in present-day South 24 Parganas, West Bengal. He died on September 5, 1995, in Kolkata. He spent his childhood in the tea gardens of Assam, where his father, Dr. Gyanendra Chowdhury, worked as a doctor.

An Irish colleague left behind a gramophone and a collection of Western classical records. Young Salil listens to Mozart, Beethoven, Tchaikovsky and Chopin every day. At the same time, he heard Assamese and Bengali folk tunes all around him.

He witnessed death and starvation on the streets of Calcutta during World War II and the 1943 Bengal famine. This experience pushed him towards left politics and the Communist Party of India. He joined the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), wrote plays and protest songs, and soon became a full-time cultural worker and underground activist for some years.

In this context, the year 2025 is especially significant, as we are celebrating 100 years since the birth of Salil Chowdhury and revisiting his legacy with renewed attention.

Over his long career, he:

- Has composed music for over 75 Hindi films and numerous Bengali and Malayalam films.

- Wrote and composed hundreds of songs in 10–13 Indian languages.

- Worked as a story writer, scriptwriter, poet and director (for the film Pinjre Ke Panchhi in 1966).

- Helped start India’s first secular choirs, including the Bombay Youth Choir and the Calcutta Youth Choir.

Quick bio at a glance

| Aspect | Details |

| Full name | Salil Chowdhury (also written Salil Choudhury) |

| Birth | 19 November 1925, Ghazipur, South 24 Parganas, Bengal Presidency |

| Death | 5 September 1995, Kolkata, West Bengal |

| Early life | Tea gardens of Assam, exposed to Western classical and local folk music |

| Education | Harinavi DVAS High School; Bangabasi College, University of Calcutta |

| Main occupations | Composer, lyricist, writer, director, arranger, flautist |

| Political leaning | He is a Marxist and a member of the CPI and IPTA cultural front. |

| Approx. output | He has contributed to over 75 Hindi films, numerous Bengali and Malayalam films, and over 1000 songs in total. |

| Key awards | He received the Filmfare Award for Madhumati, the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 1988, and several other awards. |

When Marxism Found a Melody: His Political Awakening

Salil’s Marxism did not come only from theory. It came from what he saw around him. He saw the harsh life of tea-garden labourers in Assam. He saw peasants in Bengal fight for land. He saw famine victims and war refugees in Calcutta. Out of these images, his politics—and his music—were born.

From Bengal Famine to Farmers’ Struggles

In 1943–44, Salil watched starving people die on the streets during the Bengal famine, in which an estimated 3–5 million people perished. Colonial policy and hoarding exacerbated the famine.

He then moved to a village in 24 Parganas, where he saw a peasant uprising related to the struggles that later shaped the Tebhaga movement. Sharecroppers (bargadars) demanded two-thirds of the crop from landlords instead of one-half. Salil started writing songs for these peasants and soon became deeply involved in their cause.

Salil composed marching songs for mass gatherings in Calcutta during the 1946 All-India postal strike and wider workers’ actions. Classic Bengali protest songs still recall some of these early works.

Political Roots: Key Events

| Period / Event | Influence on Salil Chowdhury |

| Assam tea-garden childhood | Saw class divide and labour exploitation |

| Bengal famine (1943) | Witnessed mass hunger and death; moved strongly towards Marxism |

| Peasant agitations (Tebhaga era) | Wrote songs for sharecroppers; learnt rural rhythms and idioms |

| 1946 postal strike & workers’ actions | Composed mass songs for rallies and demonstrations |

| Underground CPI work | Went underground in the Sunderbans; wrote plays and songs |

IPTA and the Birth of Protest Songs

In 1944–45, Salil joined IPTA (Indian People’s Theatre Association), the cultural wing of the Communist movement. IPTA used drama, music and dance to speak about famine, colonial rule, and social injustice.

Within IPTA, Salil became:

- A flautist and composer

- A writer of mass songs (gana sangeet)

- A key figure in taking political art to villages and small towns

His early hit, “Bicharpoti Tomar Bichar,” was written in 1945 around the INA trials. It used a kirtan-like tune but carried a powerful message: the people will judge injustice.

Later he called many of these works “songs of consciousness and awakening”—songs meant to wake people up, not lull them to sleep.

IPTA phase at a glance

| Item | Details |

| Organisation | Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) |

| Salil’s roles | Composer, lyricist, flautist, playwright, and organizer |

| Typical song style | March rhythms, group choruses, simple but powerful tunes |

| Main themes | Anti-colonial struggle, famine, peasant rights, workers’ strikes |

| Legacy | In Bengal and among left cultural groups, many IPTA songs continue to resonate. |

Crafting a New Sound: Blending East, West and the Working Class

Salil wanted to create a sound that crossed borders. He once said he wanted a style that was “emphatic and polished, but never predictable” and that could rise above narrow boundaries. His music is renowned for its East–West fusion, but that fusion always serves the stories of common people.

East–West Fusion, But Rooted in the People

From his youth in Assam, he listened to Western symphonies on the gramophone while hearing folk tunes and natural sounds outside. This double world later became his signature.

Common features of his compositions:

- Rich Western-style harmony and chord progressions

- Use of counterpoint and multiple vocal lines (very clear in his choir works)

- Melodies based on Indian ragas or folk scales

- Strong rhythmic drive that suited marching songs and dance numbers

- Emotional focus on workers, peasants, migrants, and the lonely urban poor

So even when the music sounded “Western” or sophisticated, the heart of the song stayed with ordinary people.

East–West blend overview

| Element | How it appears in his music |

| Western classical | Orchestral arrangements, strings, woodwinds, choral harmonies |

| Indian classical | Raga-based melodies give emotional color and depth. |

| Folk traditions | Simple, memorable motifs; village rhythms; work songs |

| Political concern | Lyrics about hunger, land, labor, prisons, and hope. |

From Gana Sangeet to Film Songs

Salil entered films first in Bengali cinema, with movies like Poribartan (1949) and Barjatri (1951). His big national breakthrough came with Bimal Roy’s Hindi film Do Bigha Zamin (1953), based on his Bengali story “Rikshawala.” He wrote the story and also composed the music.

Even after he moved fully into film work, the spirit of mass songs remained:

- Many protagonists are peasants, clerks, workers, or small-town dreamers

- Social themes—land loss, migration, loneliness—stay present even in romantic songs

- Choruses and group singing continue to appear

Gana sangeet to cinema transition

| Phase | Salil’s approach |

| IPTA/mass songs | Direct slogans, clear Left politics, group singing in rallies |

| Early Bengali films | Realistic stories, rooted in village and small-town Bengal |

| Hindi/multilingual films | Wider themes, but with strong humanism and class awareness |

Cinema as a Battleground: Salil Chowdhury in Indian Films

For Salil Chowdhury, film music was not just entertainment. It was a tool to speak about society, reach large audiences, and keep a political conscience alive inside popular culture.

Do Bigha Zamin and the Cinema of the Oppressed

Do Bigha Zamin (1953) is one of the landmarks of Indian cinema. Directed by Bimal Roy, it tells the story of a poor peasant, Shambu, who loses his two bighas of land to a landlord and is forced to pull a rickshaw in Calcutta.

Salil’s role in this film was unique:

- He wrote the original Bengali story “Rikshawala” on which the film is based

- He composed the full songs and background score

The film won:

- Cannes International Prize (Prix International) in 1954

- The All India Certificate of Merit for Best Feature Film at the 1st National Film Awards

- The Filmfare Award for Best Film

Songs like “Dharti kahe pukar ke” use a marching rhythm and earthy tune. Researchers have pointed out how it blends the feel of a Soviet Red Army song with Indian melodic structure—a perfect symbol of Salil’s Marxist internationalism and Indian roots.

Do Bigha Zamin—key facts

| Item | Details |

| Year of release | 1953 |

| Director | Bimal Roy |

| Story source | Inspired by Tagore’s “Dui Bigha Jomi” and Salil’s story “Rikshawala” |

| Music director | Salil Chowdhury |

| Themes | Land dispossession, industrialisation, urban poverty |

| Major awards | Cannes Prize, National Award, Filmfare Best Film |

Beyond Bengal and Bombay: A Pan-Indian Marxist Melody

Salil did not stay limited to one language or region. He composed for films in at least 10–13 Indian languages. His work stretches across Bengali, Hindi, Malayalam, Marathi, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Gujarati, Odia and Assamese cinema.

Some major milestones:

- Hindi – Madhumati (1958): He won the Filmfare Award for Best Music Director. The film also won the National Award for Best Feature Film in Hindi.

- Hindi – Anand (1971), Mere Apne (1971), Chhoti Si Baat (1976): Films dealing with illness, disillusionment, and middle-class life in big cities.

- Malayalam – Chemmeen (1965): A story about fisherfolk, caste and taboo on the Kerala coast. The film received the President’s Gold Medal for Best Feature Film and Salil’s score is still celebrated.

Beyond films, he played a central role in choir music:

- Founded the Bombay Youth Choir, India’s first secular choir, in 1958

- Co-founded the Calcutta Youth Choir with Ruma Guha Thakurta and Satyajit Ray; the choir won a prize at the Copenhagen Youth Festival in 1974 and still performs his songs today

Film and choir work—snapshot

| Area | Examples / details |

| Hindi cinema | Do Bigha Zamin, Madhumati, Anand, Mere Apne, Chhoti Si Baat |

| Bengali cinema | Poribartan, Barjatri, Raat Bhore, Pasher Bari and more |

| Malayalam cinema | Chemmeen, Ezhu Rathrikal, Nellu, Swapnam |

| Choir work | Bombay Youth Choir, Calcutta Youth Choir |

| Key recognitions | Filmfare, National Awards, Sangeet Natak Akademi Award (1988) |

Was Salil Chowdhury Depoliticized Over Time?

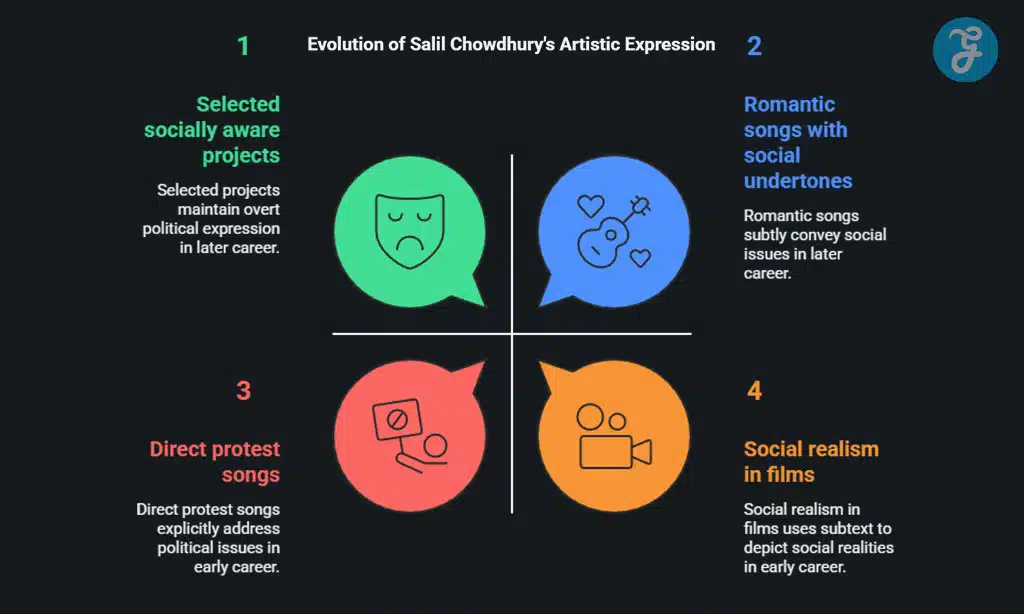

Today, many people remember Salil Chowdhury mainly for romantic or nostalgic film songs. His activist past is less visible in popular memory. Scholars studying his work argue that this is part of a wider process: as the IPTA movement declined and the political climate changed, many radical artists were rebranded mainly as entertainers. Their Marxist role was downplayed.

From Slogans to Subtext

In his early IPTA days, Salil’s songs spoke very directly:

- They mentioned bullets, prisons, police, landlords and imperialists.

- The target of anger was clear.

- The songs were used in real struggles.

In his later film work, the politics often moved into subtext:

- A song might show a poor clerk in a cruel city.

- A peasant might lose land inside a family drama.

- A lonely migrant might express alienation in what seems like a love song.

The slogans softened, but the class perspective stayed.

Change of tone—then and later

| Period | Style of political expression |

| 1940s–early 1950s | Overt protest, explicit Marxist language, direct use in rallies |

| 1950s–1960s films | Social realism; strong empathy for workers, peasants, small clerks |

| 1970s–1990s | Mix of romantic/nostalgic songs and selected socially aware projects |

The Risk of Remembering Only the Melodies

If we remember only the “sweet” side of Salil, we lose the meaning of his life.

The best current studies on his protest songs stress that he should be seen as an “artivist”—an artist and activist at once. They show how his lyrics captured real events, from famine and Tebhaga to strikes and state repression.

At the same time, recent media pieces—including a 2024 article in The Telegraph on his 99th birth anniversary—have started to restore this full picture, tracing his journey from gana sangeet to Bengali and Hindi film songs.

Film festivals are also honoring him as a serious, socially aware artist. The 56th International Film Festival of India (IFFI 2025) and the Kolkata International Film Festival’s 2025 program have announced special screenings of classics like Do Bigha Zamin and Madhumati to mark his centenary.

Image vs reality

| Popular image today | Fuller reality |

| “Melody king,” “great arranger” | Marxist activist and people’s artist |

| Film composer only | Also protest-song writer, playwright, short-story writer, director |

| Romantic/nostalgic focus | Strong record of anti-famine, anti-feudal, pro-worker songs |

Why Salil Chowdhury Matters in Today’s India

Many issues Salil wrote about are still with us: agrarian crisis, migration, job insecurity, urban loneliness, rising inequality, and pressure on dissenting voices. At the same time, India is seeing a new wave of protest music—in hip-hop, folk revivals, campus bands, and street performances. Salil’s work offers a living example of how to combine artistic quality and political content.

Inequality, Authoritarianism and the Return of Protest Music

Salil’s songs show that:

- Protest music can be lyrically rich and musically complex, not just loud slogans.

- Political art can speak through stories, emotions and images, not only speeches.

- One artist can work in many languages and styles and still keep a clear ethical line.

Today, when musicians and filmmakers explore themes like unemployment, caste violence, or state repression, they often follow a path that IPTA and Salil helped open.

Modern issues and Salil’s themes

| Today’s concern | Example of connection in Salil’s work |

| Farmer distress, land grabs | Do Bigha Zamin; peasant songs from the Tebhaga period |

| Urban precarity, gig work | Stories of clerks, migrants, job-seekers in many Hindi/Bengali songs |

| Attacks on dissent | IPTA-era songs about bullets, prisons, and the “judge of the people” |

| Need for inclusive, secular culture | Choir work, multi-lingual compositions, focus on common people |

Final Thoughts: The Living Echo of Salil Chowdhury

Salil Chowdhury proved that music can be both beautiful and brave. He refused to separate melody from Marxism or art from the everyday struggles of workers and peasants. When we listen to his songs now, we hear not just classic film hits but echoes of marches, strikes and unheard voices.

Honoring him is not only about nostalgia; it is about remembering what his songs stood for—justice, dignity and hope. If we too can join skill with conscience in our own work, then the true spirit of Salil Chowdhury lives on, and his music keeps asking us to stand with the people his melodies loved.