On the evening of December 14, 1971, a strange and curdled silence descended upon Dhaka. To the casual observer, it might have seemed like the hush of anticipation. The Allied Forces—the Indian Army and the Mukti Bahini—were tightening the noose around the city. The roar of artillery was drawing closer; the Pakistani occupation forces were on the verge of surrender. Freedom was not just a dream anymore; it was a matter of hours.

But in the darkened neighborhoods of Dhanmondi, Katabon, and Kalabagan, the silence was not one of hope. It was the silence of the hunter stalking its prey.

While the world focused on the crumbling frontlines, a different kind of operation was being launched under the cover of a strict curfew. Mud-smeared microbuses, engines idling quietly, began to prowl the streets. They were not looking for soldiers, guerrillas, or arms caches. They were looking for university professors. They were hunting journalists. They were seeking out doctors, playwrights, and philosophers.

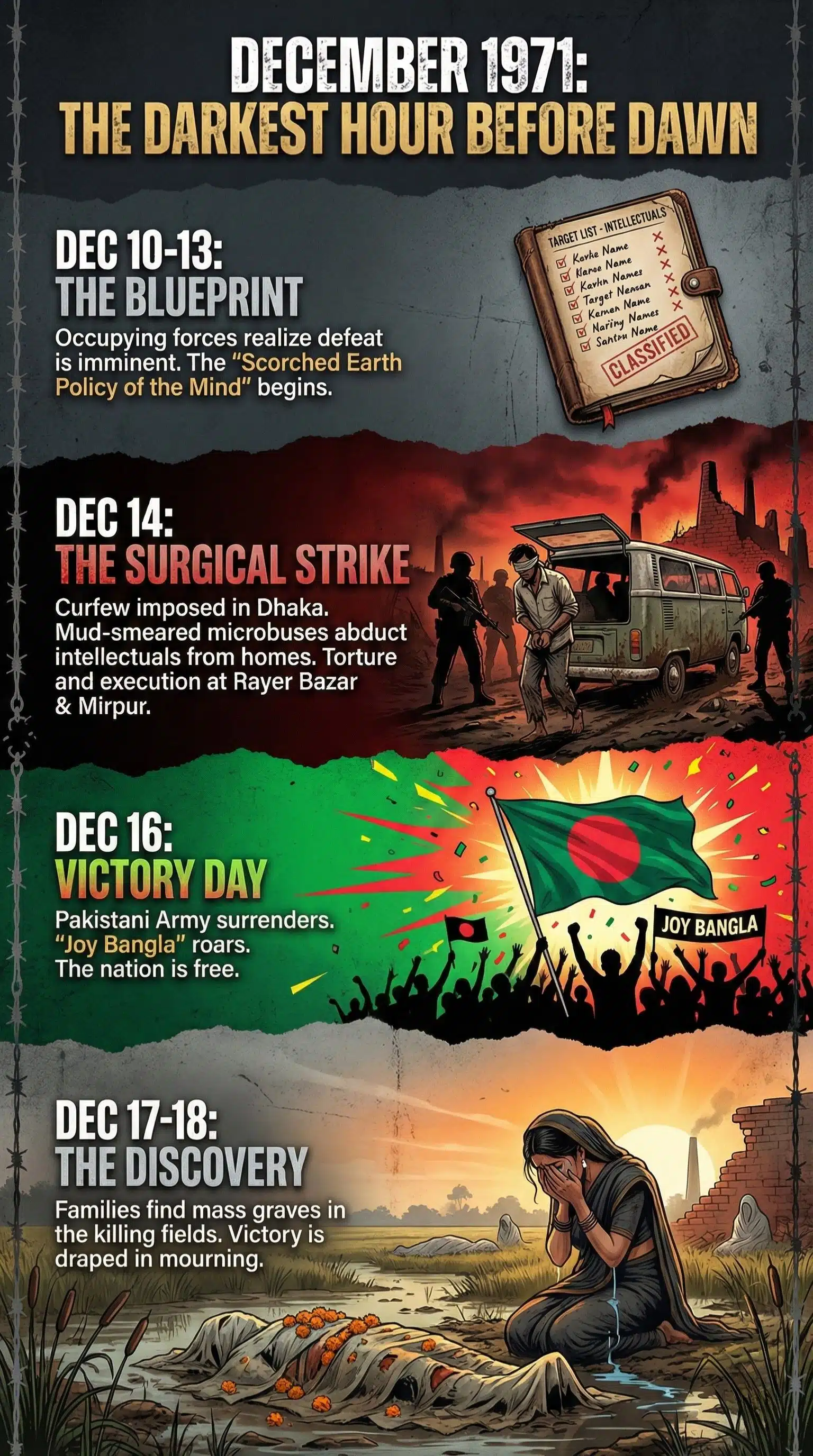

It was a surgical strike against the nation’s soul. The occupying forces, realizing that their military defeat was inevitable, initiated a “scorched earth” policy—not of the land, but of the mind. They knew they could not hold the territory of Bangladesh, so they decided to ensure that the new nation would be born crippled, decapitated of its best thinkers and visionaries.

As the microbuses moved through the fog that night, they carried away the architects of our identity. Two days later, the country would erupt in the joy of Victory Day. But for the families of those taken on the 14th, the war would never truly end.

The Blueprint of a Crippled Nation

To understand the tragedy of Martyred Intellectuals Day, one must understand that this was not the chaotic, random violence of a retreating army lashing out. It was a cold, calculated administrative decision. It was a genocide of the intelligentsia.

The blueprint for this massacre was rooted in a dark realization by the Pakistani establishment: Bangladesh is inevitable. If they could not stop the birth of the nation, they would ensure it was a “failed state” from its very first breath. How does a new country survive if you kill its engineers? How does it draft a constitution if you kill its lawyers? How does it heal its wounded if you kill its top surgeons? How does it teach its children history if you kill its writers?

This premeditation is not a matter of speculation; it is a matter of record. After the surrender, a diary belonging to Major General Rao Farman Ali, the military advisor to the Governor of East Pakistan, was recovered from the ruins of the Governor House. It contained a list of names—Bengali intellectuals who were deemed “miscreants” and “traitors” for their support of Bengali nationalism.

However, the Pakistan Army did not carry out these executions alone. They outsourced the grim task to the Al-Badr and Al-Shams, paramilitary wings composed of local collaborators. The tragedy of Al-Badr was its composition; many of its members were students, largely from the Islami Chhatra Sangha. These were educated young men who knew exactly who to target. They did not need directions to the houses of the professors; they had sat in their classrooms.

This betrayal was intimate and personal. The list of targets was not just a military objective; it was a purge of the secular, cultural backbone of Bengali nationalism that had been growing since the Language Movement of 1952. The intellectuals were targeted not because they held guns, but because they held ideas—ideas of secularism, democracy, and Bengali identity that the occupation forces found more dangerous than any bullet.

The Night of the Long Knives

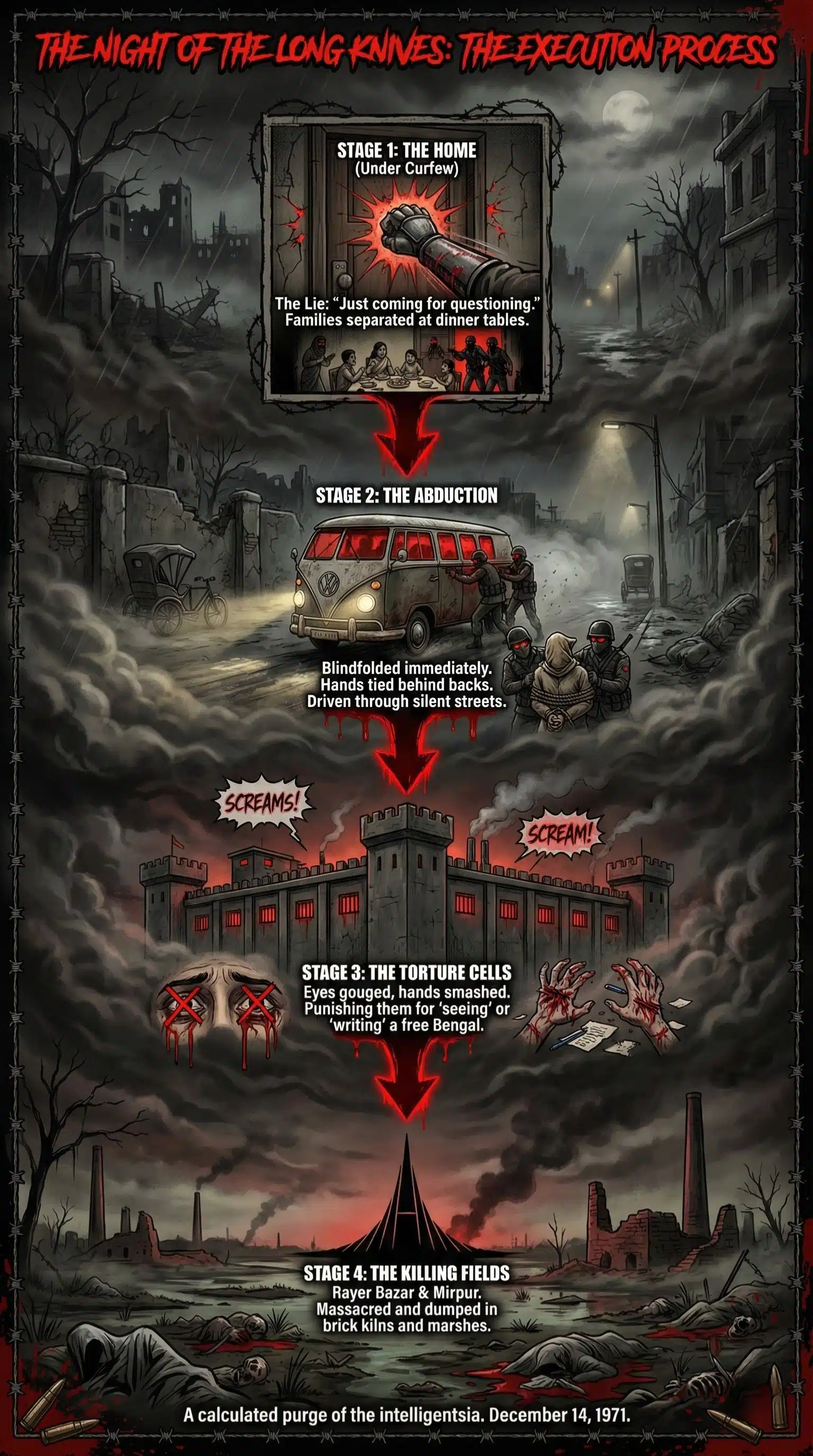

The methodology of December 14 was terrifyingly efficient. The city was placed under a round-the-clock curfew, trapping citizens in their homes. This turned the neighborhoods of Dhaka into a hunting ground where escape was impossible.

The narrative of that night is stitched together from the hauntingly similar testimonies of survivors. It usually began with the sound of heavy boots on the stairs. A knock on the door, loud and authoritative. When the families opened the door, they were met by masked men or young men in militia uniforms, often accompanied by army personnel.

The explanation was always a lie, delivered with chilling calm: “We just need to take him for questioning. He will be back in the morning.”

Fathers were pulled away from dinner tables. Husbands were dragged out of bedrooms. Many were blindfolded immediately in front of their weeping children. Their hands were tied behind their backs, and they were shoved into the waiting microbuses.

They were taken to torture cells set up across the city, most notably at the Physical Training College in Mohammadpur and the Nakhalpara MP Hostel. But their final destination was the killing fields.

The names Rayer Bazar and Mirpur Jalladkhana are now etched into the national consciousness, but on that night, they were desolate brick kilns and marshlands on the outskirts of the city. In the darkness of winter, these brilliant minds—men and women who had lectured on philosophy, performed life-saving surgeries, and written poetry—were lined up in the mud.

The brutality inflicted upon them was symbolic. Eyewitness accounts and forensic evidence later revealed that many were tortured before being shot. Eyes were gouged out—perhaps to punish them for “seeing” a free Bengal. Hands were smashed—punishing the writers for their words. Hearts were targeted. They were massacred and dumped into the swamp, their bodies left to decompose in the cold December air.

Profiles in Courage: The Voices We Lost

Statistics often numb us to the reality of tragedy. To truly comprehend the loss of December 14, we must look at the individuals. We must look at the empty chairs they left behind.

Munier Chowdhury: The Educator

A giant of Bengali literature, Munier Chowdhury was a playwright and a professor whose works defined a generation. He was a man of immense principle, having rejected state awards from the Pakistani government in protest of their oppression. On the 14th, he was abducted from his home. He was a man who lived by the word, and he died for it. His body was never identified with certainty, leaving his family with a lifetime of unresolved grief. His loss was a decapitation of Bengali drama and liberal arts.

Dr. Alim Chowdhury: The Betrayal

Dr. Alim Chowdhury was an eminent eye specialist, but his contribution went beyond medicine. He secretly treated wounded freedom fighters, risking his life daily. His death is a harrowing example of the internal betrayal that characterized the time. He was betrayed by a man named Maulana Mannan, whom Dr. Alim had sheltered in his own home to protect from the war. Mannan, a collaborator, handed over his benefactor to the Al-Badr. The man who saved Vision was plunged into eternal darkness by the very person he tried to save.

Selina Parvin: The Fearless Voice

The genocide did not spare women. Selina Parvin, the editor of the literary magazine Shilalipi, was a bold voice for resistance. A single mother, she worked tirelessly to keep the spirit of nationalism alive through her publication. She was dragged from her home on December 14, leaving behind a young son who would grow up waiting for a mother who never returned. Her death proved that the Al-Badr feared the pen of a woman just as much as the rhetoric of a politician.

Dr. Govinda Chandra Dev: The Gentle Philosopher

Dr. G.C. Dev was a man of peace, a philosopher of synthesis who believed in the unity of all religions. A professor at Dhaka University, he was known for his gentle demeanor and his love for his students. The brutality visited upon such a harmless, high-thinking soul exposed the sheer inhumanity of the perpetrators. They did not just kill a man; they killed the very idea of tolerance.

These are but a few names. The list includes Shahidullah Kaiser, the novelist who never finished his story; Anwar Pasha, who wrote Rifle Roti Aurat; and countless others. And beyond Dhaka, in districts like Sylhet, Chittagong, and Khulna, local teachers, rural doctors, and community leaders were similarly purged, their stories often lost to the broader national narrative.

The Aftermath: Victory Draped in Black

On December 16, 1971, the Pakistani army surrendered. The racecourse ground roared with “Joy Bangla.” The green and red flag was hoisted. It was the greatest day in the history of the Bengali people.

But for thousands of families, victory was a hollow sound. While the streets celebrated, wives and mothers were rushing to Rayer Bazar and Mirpur, wading through the marshes, turning over corpses in a desperate search for their loved ones.

The scenes at Rayer Bazar on December 17 and 18 were apocalyptic. The famous photograph taken by Rashid Talukder—of a disjointed, decomposed body lying in the swamp—shocked the world. It showed the price of freedom.

The immediate impact on the new nation was devastating. Bangladesh began its journey with a “brain drain” created by genocide. The vacuum was palpable. The universities had lost their deans, the hospitals had lost their department heads, and the newspapers had lost their editors. The administrative and intellectual infrastructure needed to rebuild a war-torn country was shattered. It took decades for the nation to recover from this intellectual deficit, and one can argue that the trajectory of Bangladesh’s development was permanently altered by the loss of these visionaries.

The Long Road to Justice & Legacy

The tragedy of the martyred intellectuals was compounded by what followed: the era of impunity. After the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1975, the political landscape shifted. The very collaborators who had orchestrated the killings on December 14 were rehabilitated. Some became ministers; others became influential businessmen.

For decades, the families of the martyrs had to watch the murderers of their fathers and husbands drive the flag-bearing cars of the state. It was a second death for the intellectuals—a death of justice.

It was not until the establishment of the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) in 2010 that the wheel of justice began to turn. The trials and subsequent executions of Al-Badr leaders like Matiur Rahman Nizami and Ali Ahsan Mohammad Mojaheed for masterminding the intellectual killings offered a semblance of closure. It was a legal acknowledgement that these were not just casualties of war but victims of crimes against humanity.

However, the legacy of the martyrs faces a new challenge today: the fading of memory. As we move further away from 1971, the visceral horror of that day risks becoming just another date on the calendar.

Final Words: The Torch Remains

Martyred Intellectuals Day is not merely a day of mourning; it is a day of reckoning. It forces us to ask: Have we built the Bangladesh they died for?

The occupying forces killed the thinkers because they wanted to kill the ideas of secularism, equality, and justice. If we allow those ideas to wither—if we allow intolerance to rise or history to be forgotten—then we allow the Al-Badr to win retroactively.

The torch has now passed to a new generation. It is not enough to post a black banner on social media. We must read the plays of Munier Chowdhury. We must uphold the journalistic integrity of Selina Parvin. We must practice the tolerance of Dr. Govinda Chandra Dev.

They never came home so that we could have a home. They were silenced so that we could speak. The only way to truly honor them is to ensure that the nation they died dreaming of remains awake, aware, and intellectually alive.

We remember them not just for how they died, but for why they lived.