On a November morning in 2016, Diego Maradona woke to news that felt like a blow to the chest. Fidel Castro was dead.

For millions of people, Castro was a cold figure on a TV screen. For Maradona, he was a friend, a mentor, almost a second father. In later years, Maradona would say that Castro helped save his life when drugs and fame had pushed him to the edge.

Four years later, on 25 November 2020, Diego himself died. The date was uncanny. Fidel Castro had died on 25 November 2016. They left the world on the same calendar day, separated by four years, and even by another football icon, George Best, who died on the same date back in 2005.

For some, this is just coincidence. For others, it feels like a story—almost too neat to be real. A boy from a poor neighborhood in Buenos Aires. A revolutionary from the mountains of Cuba. A left foot that shook stadiums. A bearded comandante who shook governments.

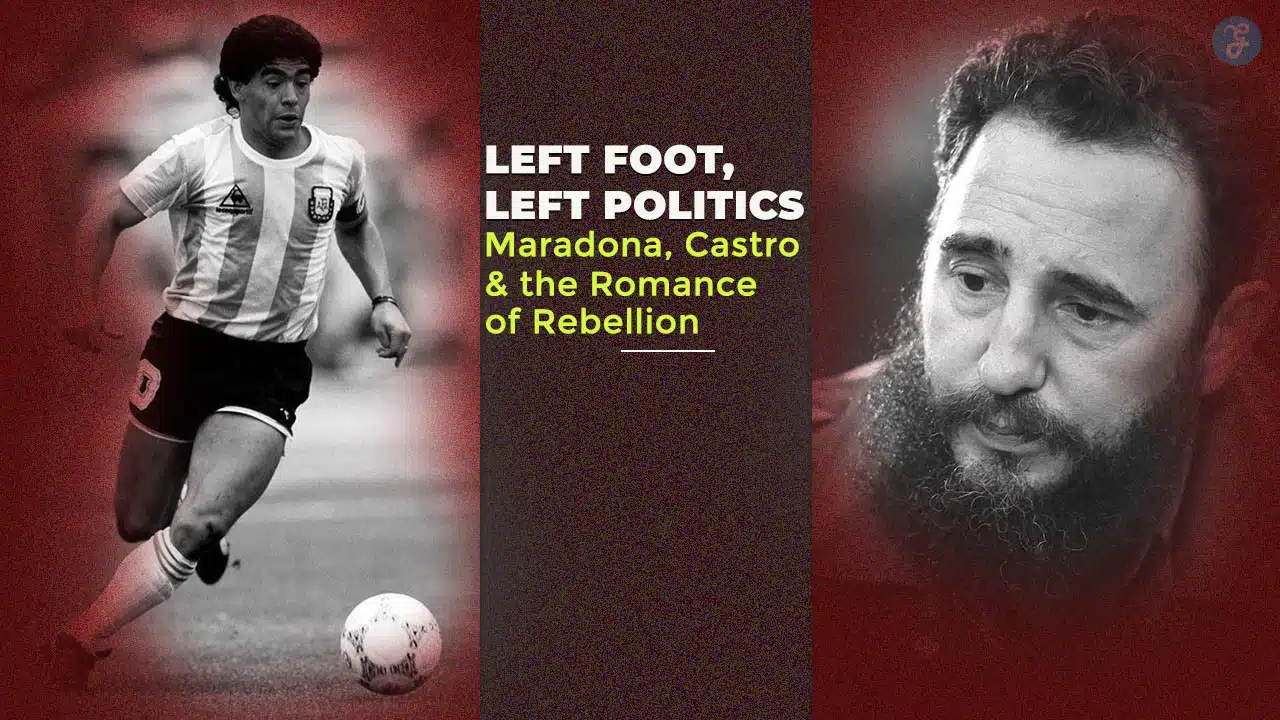

This article looks at the Maradona–Fidel Castro relationship as more than gossip. It explores how a football genius fell in love with a revolution, why that bond charmed many people in the Global South, and why it angered many others. It is a story of politics, addiction, friendship and the romance of rebellion—and the price that romance can demand.

Two Icons, Two Revolutions – Before They Met

Diego Maradona: From Villa Fiorito to Anti-Hero

Diego Armando Maradona was born in Villa Fiorito, a poor district on the edge of Buenos Aires. His family lived without much money, but with strong pride. Football was not just a game for him. It was a way out.

By the time he led Argentina to the 1986 World Cup title, Maradona was more than a player. He was a symbol of the poor kid beating the powerful. The infamous “Hand of God” goal against England, and the stunning solo run in the same match, turned him into a myth.

Even before his deep friendship with Fidel Castro, there were signs of Maradona’s political instinct. He spoke about inequality. He clashed with football authorities. He placed himself on the side of those “from below,” not those in suits. Journalists and writers have often called him a “rebel genius” and a “leftie on the field and in politics.”

His story—poor boy, magic feet, war with power—made it easy for him to connect with left-wing causes later in life.

Fidel Castro: The Comandante as Latin American Symbol

Fidel Castro, born in 1926, came from a very different world, yet he also grew up in a country marked by inequality. After leading the Cuban Revolution that overthrew the Batista regime in 1959, Castro became one of the most famous and controversial leaders of the 20th century.

For many in Latin America and the Global South, Castro symbolized resistance to the United States and global capitalism. He was seen as the man who stood up to Washington and survived. For others, he was a dictator responsible for repression and the denial of basic freedoms.

This sharp divide would later shape how people saw Maradona’s admiration for him. To some, Diego was standing with the poor and the oppressed. To others, he was romanticizing an authoritarian system.

How the Maradona–Fidel Castro Relationship Began

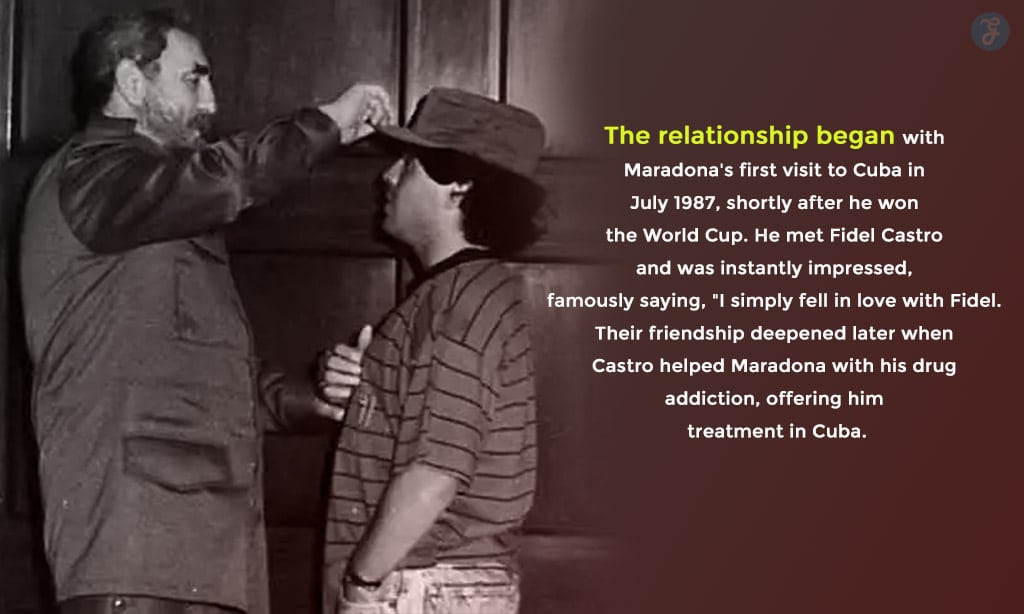

Maradona first visited Cuba in the late 1980s. One widely cited account says he went in 1987 to receive an award as the best South American athlete and met Castro during this trip.

The two men talked about sport, politics, and life. Castro loved to speak at length. Maradona, for once, was happy to listen. Later reports describe how Fidel stayed up late with him, telling stories of the revolution and asking questions about football.

It was not yet a deep bond, but the seed was planted.

Havana, Health and a Second Life

The relationship became truly close years later, when Maradona’s health collapsed.

By the late 1990s, his cocaine addiction and lifestyle had damaged his body. In 2000, after a serious health crisis, he flew to Cuba for treatment at a rehab clinic. He praised the “dignity” of the Cuban people and declared himself a rebel who admired the island.

In Havana, away from the tabloid press and the constant pressure of Europe and Argentina, Maradona tried to rebuild his life. He stayed on-and-off in Cuba for several years. Castro visited him in the clinic and kept in touch. Reports describe how the two shared long private talks, with Fidel taking a personal interest in Diego’s recovery.

At one point, Maradona said Fidel had encouraged him to consider going into politics and even called him a “second father.”

This is a key part of the Maradona Fidel Castro relationship: the idea that Castro did not only admire Maradona as a star; he saw him as a voice that could speak to millions of ordinary people.

Left Foot, Left Politics—What They Shared

Maradona never held office. He did not run a party. But over time he became a loud and visible left-wing voice in Latin America.

He supported Latin American socialist leaders such as:

- Hugo Chávez in Venezuela

- Evo Morales in Bolivia

- the Kirchners in Argentina (Néstor and Cristina)

- later, Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela

He appeared on Chávez’s TV show and even joined Maduro’s campaign events.

Maradona often attacked US foreign policy. When US President George W. Bush traveled to Argentina in 2005, Maradona joined protests and called him a “murderer.”

His statements were often raw and emotional. They were not the careful phrases of a diplomat. For his fans on the left, this made him more authentic. For his critics, it made him reckless and irresponsible.

Anti-Imperialism as the Glue

So what exactly tied Maradona and Castro together?

At the heart of it was anti-imperialism—the belief that rich countries, especially the United States, had abused and exploited poorer nations. Castro built his image as the man who refused to bow to Washington. Maradona, born into poverty, saw his own life as a fight against powerful systems that looked down on people like him.

In Cuba, he said he admired the country because no one could call its leader a thief and because, in his eyes, the revolution defended ordinary people.

To many Argentines and Latin Americans, Maradona’s left-wing views were not surprising. They fit his football story. On the field, he was the little guy dribbling past giants. Off the field, he chose to stand with leaders who claimed to fight for the poor.

We can summarize some key shared themes like this:

| Shared Theme | Maradona’s Side | Castro’s Side |

| Anti-imperialism | Criticized US power and wars; backed Venezuela, Bolivia, Cuba | Built entire image on resisting US influence in Latin America |

| Champion of the poor | Spoke about his roots, defended slum dwellers and workers | Claimed Cuban socialism put health, education and the poor first |

| Rebellion vs authority | Fought with football bosses, FIFA, media | Led an armed revolution and one-party state |

| Charisma & myth | Seen as football god and “rebel genius” | Seen as “Maximum Leader” and revolutionary icon |

This does not mean their lives were the same. But it shows why Maradona could see in Fidel a bigger, political version of himself—a man who, in his mind, kicked against the powerful.

Maradona Castro Friendship: The Myth and the Backlash

The Maradona–Castro friendship did not come without cost. For human rights activists and many liberal or conservative critics, Castro was not just a rebel. He was the head of a one-party state that jailed opponents and limited free speech. They felt that Maradona ignored the suffering of Cubans who did not support the government.

The same pattern appeared with other leaders he admired, such as Chávez and Maduro in Venezuela. Supporters saw them as defenders of the poor. Critics saw them as authoritarian rulers who damaged democracy and the economy.

So, when Maradona called Fidel “the greatest man in living history” and proudly showed off a tattoo of Castro’s face, many fans outside Latin America were shocked.

They asked: how could a hero of the people also support leaders accused of abusing human rights?

Can You Separate the Player from the Politics?

This leads to a bigger ethical question: Can we love Maradona the football player and reject Maradona the political figure?

Football fans face this kind of question often. Many great stars have done or said things that disturb us. With Maradona, the issue is sharper because his politics were so loud and public, and because they were tied to leaders who divide opinion so deeply.

Some people say yes, we can separate them. They argue that Maradona’s art on the pitch stands on its own. It gave joy to millions. It belonged to everyone, whatever their politics.

Others say no. They argue that once a person uses their fame to push certain ideas or support certain leaders, we cannot ignore that. To them, to cheer the artist while ignoring the politics is a form of denial.

We can look at it in a simple way:

| Viewpoint | Main Idea |

| Separate art from politics | Enjoy his football. Politics are private opinions, not part of the game. |

| Art and politics are linked | His image and influence helped normalize controversial leaders. |

| Contextual but critical | Understand his background and motives but also recognize real harms. |

This debate will not end soon. But it is key to any honest look at the romance between Maradona and Castro.

Tattoos, TV Shows and Farewells – The Symbols of Their Romance

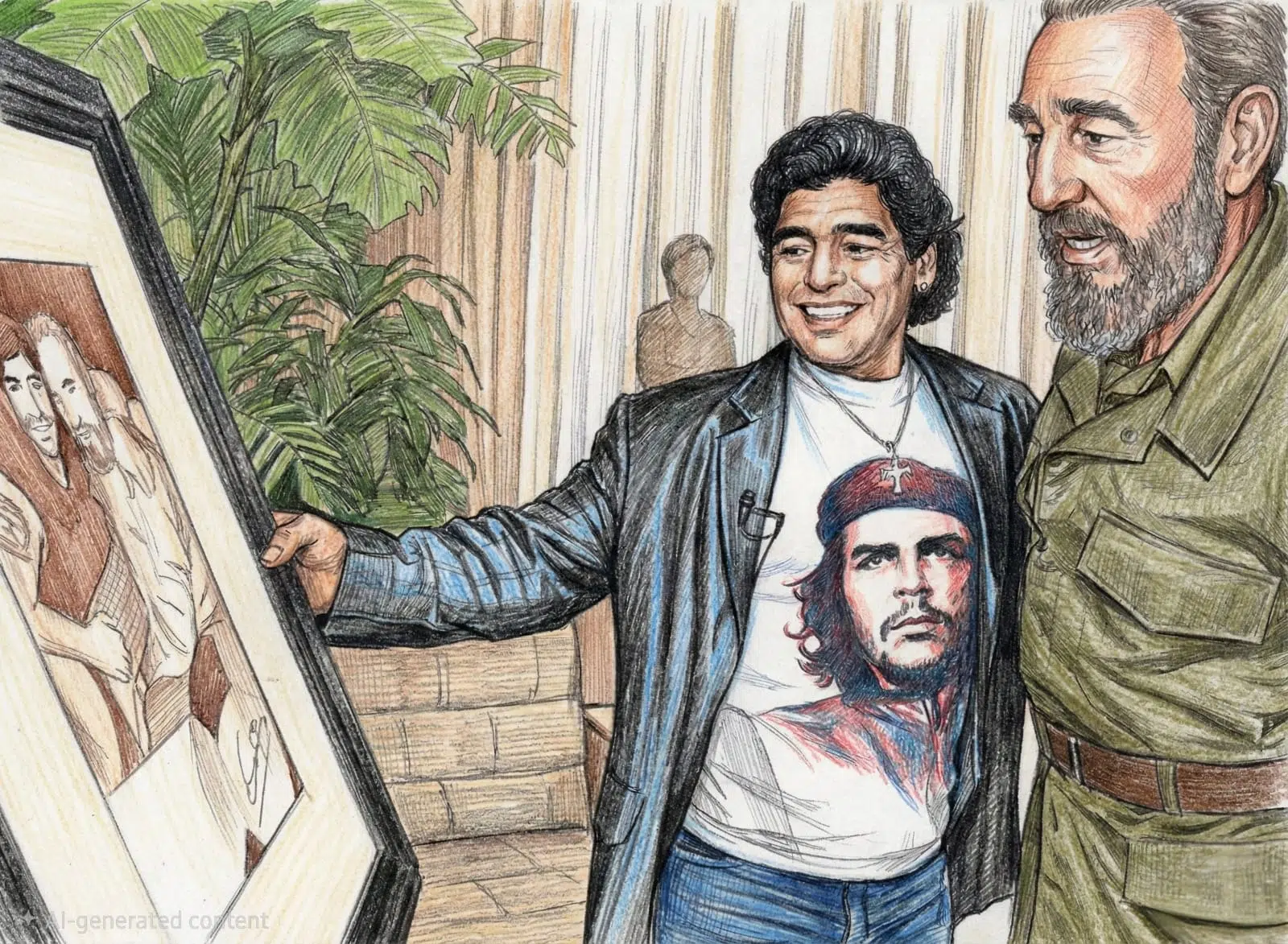

The Ink: Che on the Arm, Fidel on the Leg

Maradona did not hide what he believed. He carried it on his skin. He had a tattoo of Ernesto “Che” Guevara—the Argentine Marxist revolutionary—on his right arm. He said Che was his hero and a symbol of rebellion.

On his left leg, he had a tattoo of Fidel Castro. Photographs show him proudly pointing to these tattoos when meeting Fidel in person.

These images turned his body into a political statement. Fans copied the tattoos. Murals and banners in Naples, Buenos Aires and elsewhere often show Maradona together with Che or Fidel, or use revolutionary symbols like stars and berets.

From an SEO and storytelling point of view, this is important: many people search for “Maradona tattoo Che Guevara” or “Maradona Fidel Castro tattoo” to understand his politics. The tattoos are like a shortcut to his ideology.

Maradona on TV: Talking Politics with the Powerful

After his playing days, Maradona hosted TV shows in Argentina and elsewhere. On these shows he often invited left-wing leaders as guests.

He appeared with Chávez on Venezuelan television. He used his platform to praise leaders like Castro and Morales, and to attack US policies and global institutions like the IMF.

This turned the Maradona politics story into something larger than personal opinion. He was using his fame as leverage. He knew that millions would listen simply because he was Diego.

The Day Fidel Died – And Diego’s Grief

When Fidel Castro died in November 2016, Maradona expressed deep grief in public. He referred to Castro as a guide and said he had lost a friend who had stood by him when his life was at risk.

Many Latin American media outlets framed this as a farewell between two revolutionaries—one in politics, one in sport. In other parts of the world, the coverage was far more critical. Some headlines described Maradona as a “Castro darling,” or highlighted his “hate” toward the US, underlining how divisive his stance was.

Four years later, when Maradona died on the same calendar date, the connection between them was noted again and again. As if history itself wanted to tie their stories together.

Legacy in the Global South – What Their Bond Means Today

Long after his death, Maradona remains a cultural and political symbol. In many parts of Latin America, he is still seen as a champion of the poor. Articles and tributes repeat stories of how he spoke for people in slums, how he criticized leaders he saw as corrupt or too close to foreign interests, and how he refused to forget where he came from.

In that context, his friendship with Castro feels almost logical. Fidel becomes, in this story, the older revolutionary who gives the younger rebel comfort, support and a sense of purpose.

But in other circles—especially among Cuban exiles, human rights groups, and many European commentators—the story is darker. For them, the Maradona Fidel Castro relationship is an example of how a beloved star can whitewash or romanticize a harsh political system. They point to political prisoners, censorship and economic hardship in Cuba. They say Maradona’s glowing praise ignored those realities.

So his legacy splits into two:

- Maradona as the voice of the oppressed

- Maradona as a naive (or willing) defender of strongmen

Both images exist at the same time. Which one a person sees often depends on their own politics and life experience.

Football, Revolution and the Need for Anti-Heroes

Why are so many people drawn to figures like Maradona and Castro, even when they know the dark sides of their stories?

Part of the answer lies in the human need for anti-heroes—people who break rules, defy the powerful, and express anger that others feel but do not dare to show.

Maradona was never a clean, polite role model. He struggled with addiction, weight, temper and relationships. Castro’s rule in Cuba was marked by both social achievements (like high literacy and health coverage) and serious restrictions on political freedoms. Yet both men projected an image of defiance.

For many fans, especially in the Global South, this defiance is attractive. It says:

“We may be small, but we are not afraid.”

That emotional message helps explain why the romance of rebellion between Diego and Fidel still fascinates people. It is not only about ideology. It is also about identity, pride and a sense of standing up to centuries of inequality.

Timeline at a Glance

To see the story at a glance, here is a simple timeline of key dates related to the Maradona–Castro friendship:

| Year | Event |

| 1960 | Diego Maradona born in Villa Fiorito, Argentina |

| 1959 | Fidel Castro’s revolution takes power in Cuba (for context) |

| 1986 | Maradona leads Argentina to World Cup title; becomes global icon |

| 1987 | Maradona visits Cuba, receives sports award, meets Castro for the first time |

| 1994 | Maradona returns to Cuba after World Cup doping scandal (reported visit) |

| 2000 | Serious health crisis: Maradona goes to Cuba for rehab and medical treatment |

| Early 2000s | Maradona lives in Cuba for long periods; Castro visits him during treatment |

| 2000s | Maradona gets tattoos of Che Guevara (arm) and Fidel Castro (leg) |

| 2005 | Maradona joins protests against US President George W. Bush in Argentina |

| 2013 | Media highlight ongoing friendship; Maradona visits Castro again in Cuba |

| 2016 | Fidel Castro dies on 25 November |

| 2020 | Diego Maradona dies on 25 November, exactly four years later |

Final Words: The Romance and Its Price

The story between Diego Maradona and Fidel Castro is messy, emotional, and full of contradictions. On one level, it is simple: a famous footballer from the slums finds comfort and pride in the friendship of an aging revolutionary leader. A man who almost dies from addiction is given time and space to recover on a small island that he believes stands for dignity.

On another level, it is deeply complex. Castro was not just an old friend in a tracksuit. He was the head of a state accused of silencing dissent and restricting freedoms. By praising him and wearing his face on his leg, Maradona linked his own image—already surrounded by near-religious devotion—to a regime that many people consider oppressive.

This is the romance of rebellion. It can be beautiful. It can be blind.

Maradona’s left foot wrote some of the greatest passages in football history. His left politics spoke to millions who feel ignored by the global system. Together, they built a myth that is hard to separate into neat boxes of “good” or “bad.”

In the end, perhaps the most honest way to see the Maradona–Castro relationship is to hold two truths at the same time:

- Diego found real support, friendship and meaning in Castro and in Cuba.

- That friendship also tied him to a political project that harmed many people who did not have his power or his protection.

We can admire his genius, feel moved by his loyalty, and still ask hard questions about what it means when our heroes fall in love with revolutions. Would Maradona be Maradona without his politics? And would the world still argue so fiercely about him if he had simply kept quiet?