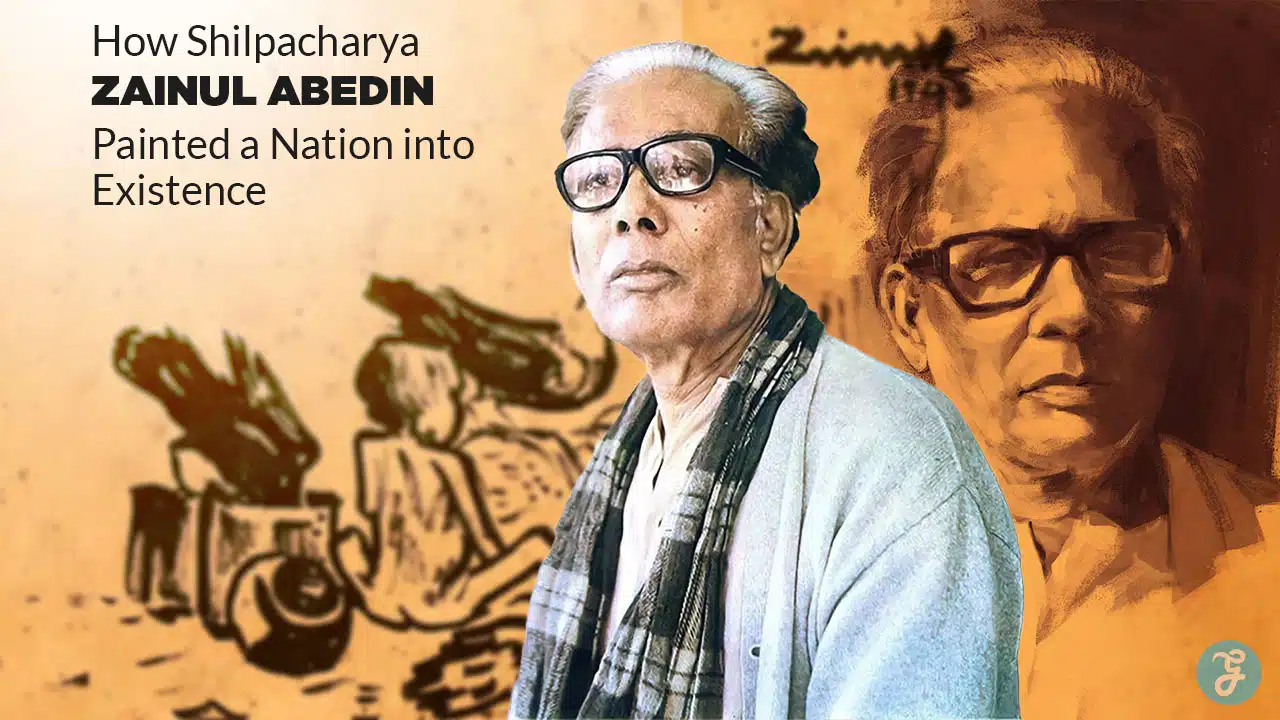

In the history of every nation, there are figures who build infrastructure, figures who write laws, and figures who fight wars. But rarely does a single individual emerge who builds the very soul of a nation. For Bangladesh, that figure is Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin. Today is his 111th birth anniversary.

To call him merely a painter is a profound understatement. Zainul Abedin was the conscience of a society in turmoil, a chronicler of human suffering, and the architect of the modern art movement in South Asia. He did not just paint what he saw; he painted what his people felt but could not speak. From the harrowing sketches of the 1943 famine to the triumphant scrolls of 1969, his canvas was the soil of Bengal, and his ink was the sweat and tears of its people.

Today, on his 111th birth anniversary, we look beyond the textbooks to explore the life, philosophy, and enduring legacy of the man who taught a nation how to see itself.

Key Facts at a Glance

-

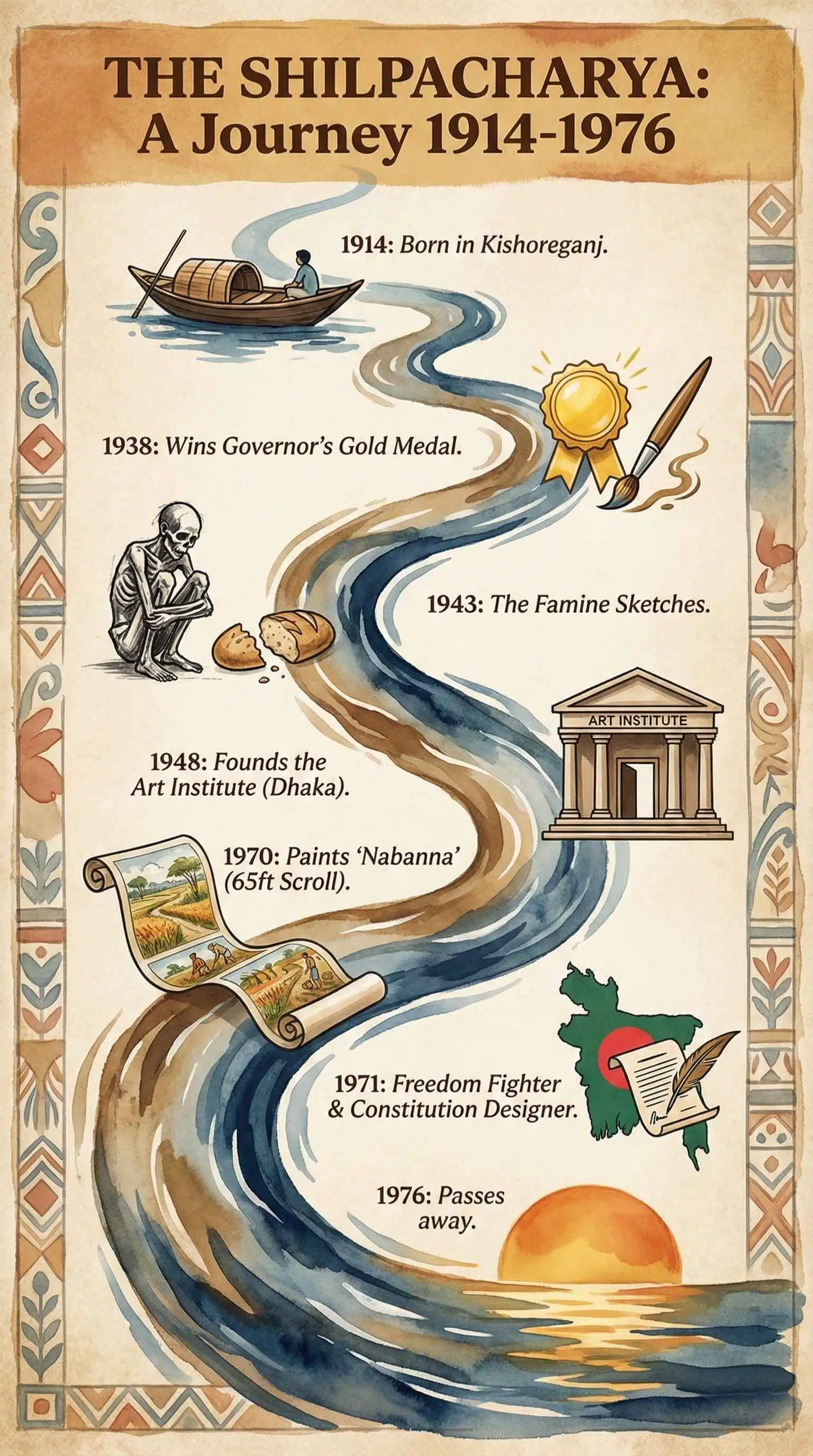

Born: December 29, 1914 (Kendua, Mymensingh)

-

Died: May 28, 1976 (Dhaka)

-

Title: Shilpacharya (“Great Teacher of the Arts”)

-

Masterpiece: The Famine Sketches (1943)

-

Institutions Founded: Faculty of Fine Arts (Dhaka University), Folk Art Museum (Sonargaon).

-

Signature Style: Bengal Modernism (social realism mixed with folk forms).

-

Global Recognition: A crater on the planet Mercury is named “Abedin” in his honor.

Zainul Abedin: The Child of the Brahmaputra

Born on December 29, 1914, in the quiet village of Kendua in the Mymensingh district (now Kishoreganj), Zainul Abedin’s first teacher was not a person but a river. The mighty Brahmaputra flowed through his childhood, shaping his artistic consciousness before he even knew what “art” was.

His father, Tamizuddin Ahmed, was a police officer, and his mother, Zainabunnesa, was a homemaker who harbored a quiet appreciation for the arts. As the eldest of nine siblings, Zainul grew up in a household that was disciplined yet vibrant. But the four walls of a house could rarely contain him. He spent hours on the banks of the river, mesmerized by the rhythmic geometry of nature: the curve of a boat’s hull, the straining muscles of fishermen pulling nets, the shifting colors of the water at dusk, and the proud, silent walk of the Santal people.

“The river is my best teacher,” Zainul would later say. It was here that he learned the power of the line. The sweeping currents of the Brahmaputra would eventually find their way into his signature brushstrokes—fluid, continuous, and powerful.

His passion was so consuming that formal schooling felt like a cage. At the tender age of 16, driven by an insatiable curiosity, he ran away from home with friends to Kolkata just to glimpse the Government School of Arts. Though he returned, his heart remained in the city’s studios. Recognizing that her son’s destiny lay elsewhere, his mother, Zainabunnesa, made a sacrifice that would change history: she sold her gold necklace to fund his admission to the Government School of Arts in Kolkata in 1933.

It was a gamble that paid off. By 1938, Zainul graduated with a first-class distinction. More importantly, his series of watercolors depicting the Brahmaputra won the Governor’s Gold Medal at the All India Exhibition that same year. At just 24, the boy from Mymensingh had announced his arrival on the grand stage.

The Fire of 1943

If the Brahmaputra defined his love for beauty, the Great Famine of 1943 defined his commitment to humanity.

Zainul was teaching at the Government School of Arts in Kolkata when the “Manvantara” struck. It was a man-made catastrophe, exacerbated by World War II policies and British colonial apathy, which left millions in Bengal starving. The streets of Kolkata, the second city of the British Empire, became a graveyard.

For a young artist trained in the romantic landscapes of European academicism and the lyrical styles of the Bengal School, this was a crisis of conscience. How could one paint sunsets when people were dying on the pavement?

Zainul put away his expensive paints and canvases. He had no money for materials, but he had a burning need to document the horror. He bought cheap, rough packing paper and used ordinary black Chinese ink applied with a dry brush.

What emerged was the Famine Sketch Series—arguably the most powerful body of work in South Asian art history. These were not delicate portraits. They were visceral, jagged, and skeletal. He drew crows picking at human corpses. He drew mothers with dried-up breasts clutching dead infants. He drew the sheer geometry of hunger—rib cages protruding like cages, limbs reduced to sticks.

The sketches were shocking. They stripped away the colonial facade of order and exposed the brutal reality of negligence. When exhibited in 1944, they catapulted Zainul to international fame, not just for their artistic brilliance but for their moral courage. The British government reportedly tried to suppress the images, fearing they would incite unrest, but the art was too powerful to silence.

Zainul had found his philosophy: Art is not a luxury; it is a document of human struggle.

A New Territory, A New Canvas

In 1947, the Indian subcontinent was partitioned. Zainul Abedin, like millions of others, found his homeland split. He moved to Dhaka, the capital of the newly formed East Pakistan.

He arrived to find a cultural desert. Dhaka was a provincial town with no art school, no galleries, and no infrastructure for artists. If a student wanted to study fine arts, they had to travel to Kolkata, Mumbai, or Lahore. For a man of Zainul’s stature, it would have been easy to settle abroad or in West Pakistan. Instead, he chose to build.

In 1948, with the sheer force of his will and the support of fellow pioneers like Quamrul Hassan, Safiuddin Ahmed, and Anwarul Huq, Zainul established the Government Institute of Arts and Crafts.

The early days were legendary. The institute started in two rooms of the National Medical School building on Johnson Road. There were only 18 students. Zainul was the principal, the teacher, and the visionary. He fought with the bureaucracy for funds, hunted for paper and pencils, and created a curriculum from scratch.

His teaching method was unconventional. Legend has it that he would draw a cow on the blackboard—starting from the tail, moving to the spine, the neck, and the head—in one continuous flow, teaching students that life is a connected rhythm. He didn’t want his students to just copy European masters; he wanted them to look at Dhaka, at the rickshaws, the storms, and the struggle of their own people.

By 1956, he had moved the institute to a custom-designed campus in Shahbagh (designed by architect Muzharul Islam), which remains the Faculty of Fine Arts (Charukola) of the University of Dhaka today. He wasn’t just teaching art; he was breeding a generation of cultural revolutionaries.

Defining ‘Bengali Modernism’

In the early 1950s, Zainul spent two years at the Slade School of Fine Art in London. It was a time of introspection. Exposed to Western modernism, abstraction, and cubism, many artists of his era lost their roots, becoming derivative of Picasso or Matisse.

Zainul, however, went the other way. He realized that “modernism” didn’t mean abandoning one’s culture; it meant reinterpreting it. He looked back at the folk art of Bengal—the dolls, the pottery, and the “Patachitra” scrolls. He saw that rural artisans had been using abstraction for centuries.

He returned to Dhaka with a new visual language—the “Bengali Style.“ This style merged the bold, geometric forms of folk art with the disciplined composition of academic training. We see this in paintings like Two Santal Women (1963) and Painyar Ma (Mother of the Python). The figures are simplified, the colors are earthy (reds, ochres, and blacks), and the lines are thick and confident.

He championed the idea that an artist must be “local” before they can be “international.” This philosophy influenced his most famous students—Qayyum Chowdhury, Rafiqun Nabi, and Monirul Islam—who would go on to define the look of independent Bangladesh.

The Scrolls of Resistance

As the political climate in East Pakistan heated up in the late 1960s, Zainul Abedin once again stepped out of the studio and into the streets. He understood that the movement for autonomy was not just political; it was cultural.

In 1969, during the mass uprising against the military regime, Zainul painted a colossal 65-foot-long scroll titled “Nabanna” (The Harvest). Painted in black ink, wax, and watercolor, Nabanna was a panoramic narrative of rural Bengal. It depicted the peasants, the harvest, the joy, and the exploitation. It was a celebration of the Bengali identity that the regime was trying to suppress. It wasn’t just a painting; it was a banner of defiance.

A year later, tragedy struck again. The Bhola Cyclone of 1970 killed nearly half a million people in coastal Bangladesh. Zainul, now 56 years old, visited the devastated island of Manpura. The scenes of death reminded him of 1943.

The result was “Manpura ’70,” a 30-foot scroll capturing the aftermath of the cyclone. The swirling lines, the twisted bodies, and the sheer scale of the work served as a metaphor for the political storm that was about to break. These scrolls cemented his status not just as an artist but as the “Shilpacharya”—the Great Teacher of the Arts.

Other works from this period, such as “Sangram” (Struggle)—depicting a powerful bull straining against its ropes—became symbolic of the Bangladeshi fight for independence. The cow was no longer just a farm animal; it was the defiant nation itself, muscles tense, ready to break free.

The Architect of a Nation

When Bangladesh gained independence in 1971, Zainul Abedin was at the forefront of nation-building.

He was one of the key figures entrusted by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to design the Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. Zainul, along with a team of artists, adorned the document with intricate folk motifs, turning the supreme law of the land into a work of art.

But his vision extended beyond paper. He feared that rapid modernization would wipe out the rich heritage of rural Bengal. In 1975, realizing a lifelong dream, he founded the Folk Art and Craft Foundation (Lok Shilpa Jadughar) in Sonargaon. He wanted a sanctuary where the skills of the weaver, the potter, and the metalworker could be preserved and honored.

He also established the Zainul Abedin Sangrahashala in Mymensingh, donating his own artworks to the public so that the people of his hometown would always have access to art.

Honors rained down on him—National Professor, honorary doctorates, and international acclaim. But he remained remarkably grounded. Stories abound of him sitting with simple farmers, smoking a hookah, and discussing the shape of a plough with the same seriousness he would discuss a Picasso.

The Legacy of Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin

Zainul Abedin passed away on May 28, 1976, succumbing to lung cancer. He was buried beside the central mosque of the University of Dhaka, at the heart of the campus he helped build.

Fifty years after his death, his relevance has only grown. In September 2024, his painting “Untitled” (1970) sold for a record-breaking $692,048 at Sotheby’s in London, signaling that the world is finally recognizing the genius that Bengal has known for decades.

But his true value cannot be measured in dollars. It is measured in the thousands of artists graduating from the Faculty of Fine Arts every year. It is measured in the “Mangal Shobhajatra” (the Bengali New Year procession), a UNESCO heritage tradition that is rooted in the folk art principles he championed. It is measured in the way Bangladeshi artists today feel unafraid to tackle social issues, knowing their “Shilpacharya” paved the way.

Final Words: Why He Matters Today

In a world that often treats art as a commodity for the elite, Zainul Abedin reminds us that art belongs to the people.

-

He taught us that a charcoal sketch on packing paper can be more valuable than an oil painting in a gilded frame if it tells the truth.

-

He taught us that we do not need to look to the West for validation; our rivers, our soil, and our people are enough.

-

He taught us that the artist is not a bystander to history but a participant.

Today, as we celebrate his 111th birth anniversary, we do not just honor a painter. We honor the man who gave Bangladesh its visual voice. As long as the Brahmaputra flows, the lines of Zainul Abedin will remain etched in the soul of this land.