Military spending is rising fast, but the real story is purchasing power: higher prices, long lead times, and munitions shortages mean governments must pay more just to stand still. NATO alone spent about $1.5 trillion in 2024, turning rearmament into a persistent inflation shock with geopolitical and fiscal consequences.

How We Got Here

For three decades after the Cold War, many governments treated defense as a manageable overhead. Budgets tightened, stockpiles shrank, and supply chains globalized. The “peace dividend” did not end military modernization, but it pushed it into slow cycles, boutique platforms, and efficiency drives that assumed warnings would come early.

The past decade broke those assumptions. Russia’s 2014 seizure of Crimea and the 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine forced Europe to confront a consumption problem it no longer had the factories to solve. At the same time, strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific accelerated demand for missiles, air defense, naval platforms, and space and cyber capabilities. The Middle East’s escalating conflicts added a second pressure front. And a global inflation surge after the pandemic hit the one corner of government procurement that cannot easily substitute cheaper inputs: weapons that require specialized metals, energetics, microelectronics, and skilled labor.

That mix produced what looks like an arms race. SIPRI estimates world military expenditure rose to $2.718 trillion in 2024, up 9.4% year over year, among the steepest annual rises in decades. NATO members accounted for about $1.506 trillion of that 2024 total, roughly 55% of global spending.

But the headline totals still understate the real shift. “Global Defense Inflation” is not only about higher budgets. It is about the gap between money and output—the way price pressure, production bottlenecks, and delivery delays force states to spend more for the same operational effect, while rivals respond and the cycle compounds.

Key Statistics That Explain The Moment

- World military spending (2024): $2.718 trillion, up 9.4% in real terms from 2023.

- NATO members’ military spending (2024): $1.506 trillion, about 55% of global spending (SIPRI methodology).

- Europe’s military spending (2024): $693 billion, up 17% year over year and 83% higher than 2015.

- EU-27 defense expenditure (2024): €343 billion, and 2025 estimate: €392 billion in current prices (about €381 billion in constant 2024 prices).

- Top-100 arms producers’ combined arms revenues (2024): $679 billion, a record.

Those are not just big numbers. They signal that defense has re-entered the same macroeconomic space as energy, industrial policy, and public debt.

Where The Money Is Going

Global rearmament is not evenly distributed. SIPRI’s 2024 regional totals show an important pattern: spending is rising across all regions, but the growth is strongest where policymakers perceive near-term war risk or alliance credibility risk.

| Region | 2024 Military Spending (US$ bn) | Real Change 2023–24 | Change 2015–24 | Share Of World (2024) |

| Americas | 1,100 | +5.8% | +19% | 40% |

| Europe | 693 | +17% | +83% | 26% |

| Asia & Oceania | 629 | +6.3% | +46% | 23% |

| Middle East | 243 (est.) | +15% | +19% | 9.0% (est.) |

| Africa | 52.1 | +3.0% | +11% | 1.9% |

The insight is not simply “Europe is spending more.” It is that rearmament has become multi-theater, so suppliers face simultaneous demand spikes for overlapping inputs: rocket motors, explosives, guidance systems, hardened chips, and air defense interceptors. That drives price pressure and delays, which then drive still higher budgets.

The New Center Of Gravity: NATO’s $1.5 Trillion Block

The “$1.5 trillion arms race” framing makes the most sense when you look at NATO as a block. SIPRI estimates NATO members spent $1.506 trillion in 2024. That is not only a measure of deterrence; it is also a measure of market power. NATO demand effectively sets production schedules for many high-end systems, from air defense to submarines.

At the same time, NATO’s own accounting (which differs from SIPRI’s open-source methodology) shows NATO total defense expenditure rising from roughly $1.305 trillion (2024 estimate) to $1.405 trillion (2025 estimate) in current US dollars. The direction matches SIPRI even if definitions differ.

The strategic implication is that alliance spending has become a substitute for arms control and confidence-building. When trust drops, budgets rise. And once industrial capacity ramps up, it creates its own political momentum because jobs, regional investment, and supply contracts become domestic constituencies.

Defense Inflation Is A Purchasing-Power Problem, Not Just A Budget Problem

When inflation hits households, it reduces real wages. When it hits defense ministries, it reduces combat power per dollar.

Two forces make defense inflation structurally sticky:

- Defense buys what the market does not mass-produce. A limited set of firms can deliver items like advanced seekers, rocket motors, naval propulsion components, and certified energetics. When demand spikes, suppliers cannot simply “add a shift” and scale the way consumer goods do.

- Defense procurement runs on long cycles. A contract signed today may deliver years later. If inflation rises mid-cycle, governments either pay more, accept fewer units, or stretch schedules—often raising costs further.

You can see the inflation wedge inside European data. The European Defence Agency estimates EU member states may reach €392 billion in 2025 in current prices, but about €381 billion in constant 2024 prices. That gap is not enormous, but it is revealing: even after a sharp spending surge, part of the “increase” is simply maintaining real value.

Now scale that logic to munitions and air defense, where demand is not a smooth trend but a cliff. If wars consume inventories faster than factories replenish them, buyers face surge pricing, accelerated overtime, and costly capacity investments.

The outcome is a paradox: governments announce historic increases and still discover they cannot buy what they want quickly. That gap is what turns rearmament into a multi-year arms race rather than a one-off budget correction.

Munitions Are The “Oil” Of Modern War And They Are Scarce

Ukraine’s war reshaped defense planning more than any platform reveal or doctrine memo. It made attrition visible again: artillery shells, rockets, drones, and air defense interceptors decide tempo.

Industry is catching up, but slowly. By 2025, U.S. and European officials and defense firms were still describing ammunition ramp-ups as multi-year efforts rather than quick fixes. Even when factories expand, they run into upstream constraints: energetics, machine tools, qualified labor, and specialized inspection regimes.

Europe has responded with industrial policy. EU states and firms have moved to expand propellant and shell production. A widely reported example was a €1 billion deal involving Rheinmetall and Bulgaria to build capacity for gunpowder and 155mm ammunition—an indicator of how Europe is trying to rebuild the “boring” parts of defense supply chains that matter most in a long war.

This is where defense inflation becomes self-reinforcing:

- Scarcity raises prices and accelerates procurement.

- Accelerated procurement pulls demand forward.

- Pulled-forward demand tightens supply further.

The strategic consequence is that stockpiles become a key measure of power again. Allies will increasingly compete not only on “who has the best aircraft,” but also on “who can sustain firing rates for months.”

Europe’s Rearmament Is Becoming Permanent Industrial Policy

Europe is no longer debating whether to spend more. It is debating how much more, how quickly, and how much autonomy it can build.

European Defence Agency data shows EU defense equipment procurement spending reached €88 billion in 2024, up 39% from 2023, and EU defense investment exceeded €100 billion for the first time, reaching €106 billion. That is a major reallocation toward equipment and modernization.

The European Commission has also built new financing architecture. Its SAFE instrument (Security Action for Europe), adopted in 2025, is designed to support joint investments in defense industrial production and capability gaps, with implementation steps pushing national plans and loan negotiations into 2026.

There are two competing readings of this shift:

- The optimistic view: Europe is finally building scale, interoperability, and predictable demand, which can reduce unit costs over time and strengthen deterrence.

- The skeptical view: fragmented procurement across 27 budgets risks duplication, incompatible systems, and sustained cost inflation if countries chase national champions instead of shared programs.

In practice, Europe’s “rearm” moment will be judged by whether it standardizes requirements and places fewer, larger orders—or whether politics locks in a patchwork that remains expensive to maintain and hard to fight with.

The Technology Race Is Moving Faster Than Procurement Systems

“Arms race” used to mean tanks, aircraft, and nuclear warheads. Today it also means drones, AI-enabled targeting, electronic warfare, space systems, cyber resilience, and missile-defense networks.

This creates a procurement mismatch:

- Technology evolves on software timelines.

- Defense acquisition often runs on hardware timelines.

U.S. Government Accountability Office assessments continue to highlight how delays and inflation contribute to cost growth in major acquisition programs. That dynamic matters even more when militaries try to integrate autonomy, sensing, and networking into platforms built on older assumptions.

The result is a two-speed arms race:

- Fast-cycle systems (drones, loitering munitions, software-defined electronic warfare), where iteration speed matters and costs scale with volume.

- Slow-cycle systems (submarines, airframes, integrated air defense), where supply chains and industrial capacity matter and inflation compounds over years.

Countries that master both speeds will hold an advantage. Those that overspend on slow-cycle prestige platforms while underinvesting in resilient networks may find themselves “modern” on paper but brittle in conflict.

Fiscal Reality Is The Constraint That Will Decide The Pace

Defense spending does not happen in a vacuum. It competes with debt interest, aging populations, energy transitions, and domestic politics.

OECD analysis has warned that higher defense spending forces difficult fiscal choices and has uncertain macroeconomic impact, especially when debt levels and interest costs are elevated. In the euro area, central bank and fiscal authorities have examined how new defense spending measures add measurable fiscal impulse over the coming years.

This is where defense inflation becomes politically destabilizing:

- It raises the ticket price of deterrence.

- It compresses room for social spending, tax cuts, or climate investment.

- It creates distributional fights over who pays and who benefits.

Some governments will try to square the circle with debt-funded defense industrial policy, arguing that domestic production creates jobs and strategic autonomy. Others will face backlash if voters perceive defense as crowding out living standards.

This tension will shape alliance cohesion. NATO can set targets, but parliaments must fund them year after year—and inflation makes the required increases larger than the headline percentages suggest.

Arms Control Is Weakening, So Budgets Are Doing The Work

One reason the spending surge feels like an arms race is that traditional guardrails are fraying. The New START treaty—extended to remain in force through February 4, 2026—is the last major bilateral U.S.–Russia strategic arms control agreement still formally standing.

If New START expires without a successor, the nuclear dimension of the arms race could re-emerge more visibly, and not only as a U.S.–Russia story. Strategic planners increasingly model three-way competition involving China as well, which tends to push requirements upward and reduce the political space for restraint.

Conventional arms transparency tools exist, but reporting and compliance remain uneven. In a world of rising distrust, governments often treat transparency as optional and stockpiles as secrets. That reinforces worst-case planning, which reinforces higher spending, and so the cycle feeds itself.

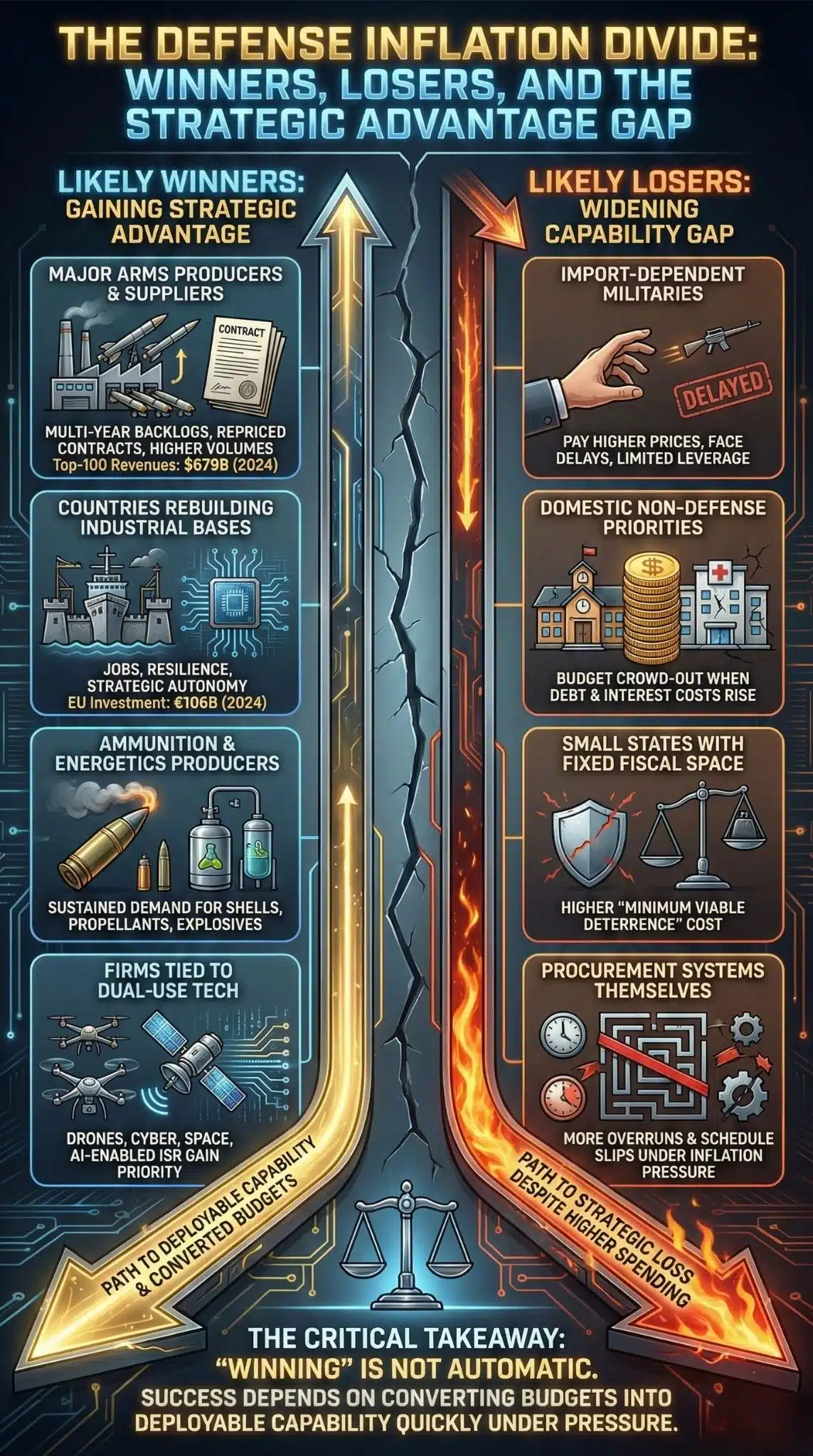

Who Wins And Who Loses In Defense Inflation

Defense inflation does not create winners and losers in the moral sense, but it does shift bargaining power and economic outcomes.

| Likely Winners | Why | Likely Losers | Why |

| Major arms producers and key suppliers | Multi-year backlogs, repriced contracts, higher volumes (Top-100 arms revenues hit $679B in 2024) | Import-dependent militaries | Pay higher prices, face delays, limited leverage |

| Countries rebuilding industrial bases | Jobs, resilience, strategic autonomy (EU investment €106B in 2024) | Domestic non-defense priorities | Budget crowd-out when debt and interest costs rise |

| Ammunition and energetics producers | Sustained demand for shells, propellants, explosives | Small states with fixed fiscal space | Higher “minimum viable deterrence” cost |

| Firms tied to dual-use tech | Drones, cyber, space, AI-enabled ISR gain priority | Procurement systems themselves | More overruns and schedule slips under inflation pressure |

The most important takeaway is that “winning” is not automatic. Countries can spend more and still lose strategic advantage if they cannot convert budgets into deployable capability quickly.

Expert Perspectives And The Best Counterarguments

A serious analysis needs to acknowledge the strongest counterpoints.

Counterargument: Higher spending is stabilizing, not escalatory.

Supporters of the surge argue deterrence requires credible force, and credible force requires investment. Under this view, spending reduces miscalculation risk because it convinces potential aggressors that war will fail—or at least be too costly.

Counterargument: Defense spending can be economically productive.

European policymakers increasingly frame defense as industrial strategy. If managed well, production and R&D can modernize manufacturing, build advanced skills, and strengthen supply chains, especially in dual-use areas like sensors, communications, and secure computing.

Counterargument: The “arms race” label is misleading because capabilities lag.

Critics argue spending figures overstate actual readiness. Persistent acquisition problems mean higher spending does not translate into proportional battlefield effect, at least not quickly.

The synthesis is this: deterrence needs investment, but inflation and industrial constraints decide whether investment becomes capability. In 2026, the constraint is shifting from “political willingness to spend” to “ability to produce and field.”

What Comes Next

The next phase of the $1.5 trillion arms race will be decided less by dramatic announcements and more by implementation capacity. Watch four milestones.

1. Whether NATO spending targets harden into enforceable national plans

NATO leaders in 2025 agreed to significantly higher defense and related security investment targets over time, combining a core defense component with broader resilience and security spending. The critical question is not the pledge—it is the annual budget path under domestic political pressure and inflation.

2. Whether Europe’s financing tools translate into factories

SAFE and related initiatives can mobilize money, but production requires permits, trained workers, and stable demand. The rearm project succeeds if it standardizes requirements and buys at scale. It stalls if national procurement politics dominate.

3. Whether munitions capacity catches up before the next crisis

Industrial expansions show movement, but timing risk remains. If a new contingency erupts in Europe, the Middle East, or the Indo-Pacific before stockpiles recover, scarcity pricing and emergency procurement will spike again.

4. Whether arms control gaps widen after February 2026

With New START’s expiration date approaching, the absence of a successor agreement could shift strategic planning toward hedging and expansion rather than restraint. Even without immediate deployments, planning assumptions alone can lock in higher budgets.

Prediction, Clearly Labeled

Analysts are likely to describe 2026–2028 as an “execution window,” where budgets are already moving but production and delivery determine outcomes. If inflation eases while capacity grows, the arms race could normalize into steady modernization. If inflation re-accelerates or new conflicts erupt, “Global Defense Inflation” may become a permanent feature of public finance rather than a temporary shock.

Final Thoughts

Global Defense Inflation matters because it changes the meaning of power. In an earlier era, advantage came from technology leaps and large standing forces. Today it increasingly comes from supply chains, surge capacity, stockpiles, and the ability to convert money into deliverable equipment under inflation pressure.

NATO’s roughly $1.5 trillion spending footprint signals the alliance has accepted a new baseline. The next question is whether that baseline buys credible deterrence or simply higher costs. The answer will be written in factory output, procurement reform, and political endurance, not speeches.