In a significant medical advancement, researchers at Duke University and Vanderbilt University Medical Center have unveiled pioneering techniques that could greatly expand the number of usable hearts for transplant surgeries in the United States. Their latest efforts focus on overcoming the logistical, technical, and ethical challenges involved in using hearts donated after circulatory death (DCD) — a largely untapped resource that could save thousands of lives each year.

This research is especially promising for infants and young children, who are among the most vulnerable patients on transplant waiting lists. If widely adopted, these new methods could dramatically reduce the growing gap between heart transplant demand and donor availability, helping patients who might otherwise die waiting for a suitable organ.

Understanding the Organ Shortage: A Growing Crisis

Every year, hundreds of thousands of adults suffer from end-stage heart failure, and for many, a transplant remains the only viable treatment. Yet due to a shortage of available donor hearts, thousands die each year without ever receiving one.

The situation is even more tragic for infants and young children. According to data from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), around 700 children are added to the U.S. heart transplant list annually, but approximately 20% die while waiting.

Despite an increasing number of donors, many hearts are never used due to how and when the donor dies. In 2023, people who died via circulatory death accounted for 43% of deceased organ donors. However, only 793 out of 4,572 heart transplants came from this category. The rest relied on donors declared dead by neurological criteria — or brain death.

The ability to safely and ethically recover hearts from DCD donors could make thousands more transplants possible each year — and this is where Duke and Vanderbilt’s groundbreaking research comes in.

What Is Circulatory Death and Why Are These Hearts Often Not Used?

Most organ donors in the U.S. are declared dead through neurological criteria, meaning the brain has irreversibly stopped functioning. In these cases, ventilators can keep the heart beating until it is surgically removed for transplant. This provides surgeons with a predictable, controlled environment for retrieval, preserving heart function.

In contrast, circulatory death occurs when a patient has a non-survivable brain injury — but does not meet the criteria for brain death. If the family chooses to withdraw life support, the heart eventually stops beating on its own. This results in a “warm ischemic period” — the time when the heart lacks oxygen-rich blood before it is removed.

While kidneys and livers can often tolerate this delay, hearts are highly sensitive to oxygen deprivation, and the delay can lead to tissue damage, compromising the organ’s viability for transplant. As a result, many transplant centers are hesitant or outright unwilling to use DCD hearts.

Conventional DCD Heart Recovery: Effective but Controversial

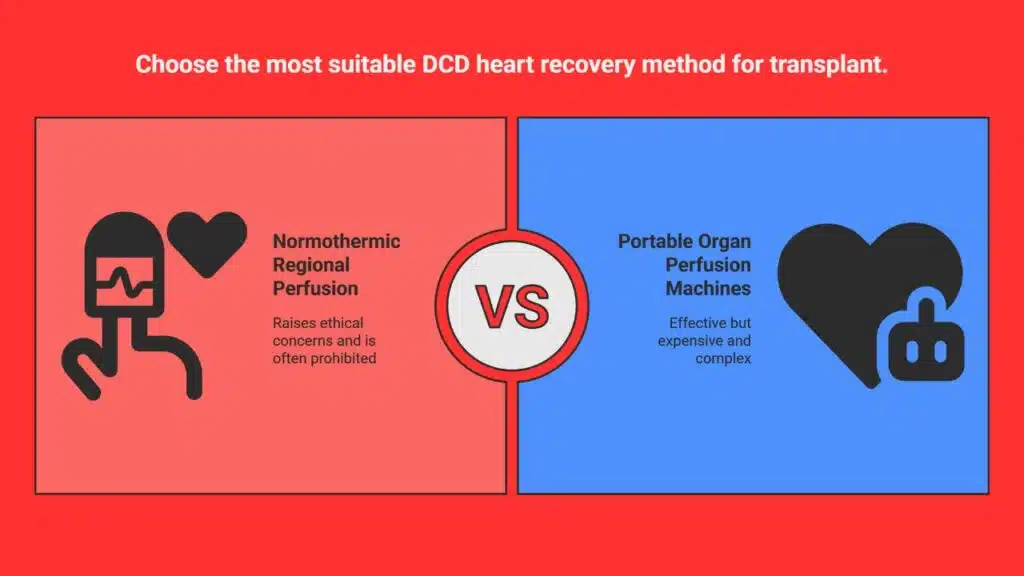

To overcome the oxygen deprivation and assess a DCD heart’s viability, transplant surgeons have traditionally relied on two main approaches:

1. Normothermic Regional Perfusion (NRP)

NRP involves restoring blood flow to the donor’s chest and abdominal organs after death by connecting them to an external pump. Crucially, blood flow to the brain is clamped off to avoid restoring brain function — maintaining the legal definition of death.

This method reanimates the heart and allows surgeons to see how well it functions before transplant. However, NRP is controversial. Critics, including ethicists and some hospital administrations, argue that artificially restoring circulation in a recently deceased body — even without restoring brain activity — blurs ethical lines. As a result, many hospitals prohibit the use of NRP altogether.

2. Portable Organ Perfusion Machines

In this technique, the heart is removed from the donor’s body and connected to a portable machine, such as the TransMedics Organ Care System. This machine mimics the human body, pumping oxygenated blood and nutrients through the heart to keep it viable until transplant.

While highly effective, these machines are extremely expensive, complex to operate, and too large for pediatric hearts. That makes them inaccessible in many hospitals and unsuitable for the youngest patients.

Duke University’s Middle-Ground: Tabletop Heart Testing for Infants

Recognizing the limitations of NRP and perfusion machines, Dr. Joseph Turek and his team at Duke University Medical Center developed a simpler, low-tech approach that can be used even in hospitals where NRP is banned.

Their method involves briefly assessing the DCD heart outside the body, using basic tubing and blood-oxygen supply, on a sterile surgical table — not a high-tech machine. This technique allows the surgical team to evaluate if the heart is beating and perfusing blood properly before committing to the transplant.

The team first practiced the procedure using piglets, which allowed them to understand how to detect viability within minutes. Then came a crucial real-world opportunity.

At another hospital, a 1-month-old infant was about to be taken off life support. The family wanted to donate the child’s organs, and the heart happened to be a perfect match for a 3-month-old baby at Duke desperately waiting for a new heart.

However, the hospital did not allow the NRP method. Dr. Turek’s team received approval to try their experimental tabletop method. In just five minutes, they observed that the heart turned pink, was beating strongly, and that the coronary arteries were filling well — all signs it could be viable.

The team immediately cooled the heart with ice, transported it to Duke, and performed the transplant successfully.

This marked a first-of-its-kind success and demonstrated that a heart can be tested for viability without controversial or expensive tools — even for pediatric patients.

Vanderbilt’s Approach: Simple, Cold Preservation Works Too

Meanwhile, at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Dr. Aaron M. Williams and his team have taken an even simpler and more scalable approach for DCD heart preservation — one that mimics the traditional method used for brain-dead donors.

Instead of reanimating the heart or testing it post-removal, they infuse the donor heart while still inside the body with a cold, nutrient-rich solution immediately after death. This flushes out waste, replenishes nutrients, and cools the organ to protect it during transport.

Williams explains that this method helps prevent damage and preserves the organ for several hours — long enough to reach the transplant center.

So far, Vanderbilt has performed about 25 successful heart transplants using this cold preservation method for DCD donors — including adult recipients.

“Our view,” said Williams, “is you don’t necessarily need to reanimate the heart to determine if it’s usable.”

Expert Opinions and Future Impact

The significance of these two research efforts is not lost on the transplant community.

Dr. Brendan Parent, director of transplant ethics and policy research at NYU Langone Health, praised the work, noting that early-stage studies like these are vital to solving the national organ shortage.

“Innovation to find ways to recover organs successfully after circulatory death is essential for reducing the organ shortage,” Parent said. “If alternatives to NRP prove safe and effective, I absolutely think cardiac programs will be thrilled — especially at hospitals that have rejected NRP.”

These methods could open up new opportunities at hospitals where ethical or financial limitations have previously prevented the use of DCD hearts.

What’s Next?

While the Duke and Vanderbilt techniques are still considered experimental, they have already resulted in real transplants and saved lives — including an infant who otherwise might not have had a chance.

The teams emphasize the need for larger clinical trials, long-term patient follow-up, and institutional support to make these methods mainstream.

If adopted on a broader scale, these simpler techniques could allow transplant centers across the country — even those without access to high-end machines or approval for NRP — to tap into a much larger pool of donor hearts.

As the gap between available organs and patients waiting continues to grow, especially among infants and those with severe heart conditions, innovative solutions like those from Duke and Vanderbilt offer new hope. By making the recovery and evaluation of DCD hearts safer, simpler, and more accessible, these researchers are helping pave the way for a more inclusive, life-saving transplant system.

The Information is Collected from NBC News and ABC News.