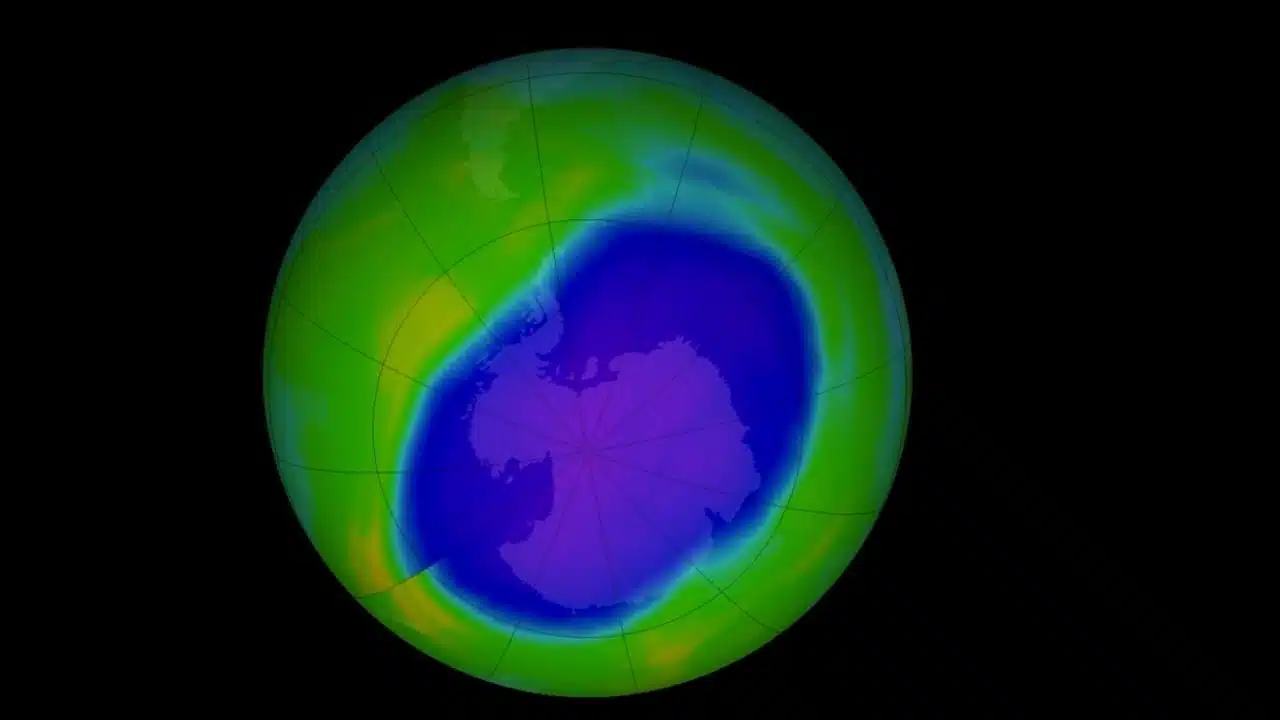

The Antarctic ozone layer — long a global environmental concern — is now showing some of its clearest signs of recovery in decades, according to new findings from NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Scientists report that while the ozone hole is still large, its recent behavior strongly suggests that international efforts to curb ozone-depleting chemicals are continuing to work, and the atmosphere is gradually healing.

On September 9, 2025, the ozone hole reached its annual maximum size of 8.83 million square miles. Even though this remains a vast region of ozone thinning, researchers emphasize that this measurement makes it the fifth smallest ozone hole since 1992 — a significant indicator that the long-term trend is headed in the right direction. The hole’s smaller size aligns with scientists’ expectations of steady improvement as concentrations of chlorine- and bromine-based chemicals decline in the stratosphere.

During the core depletion season — the period when the ozone layer is most vulnerable — which took place from September 7 to October 13 this year, the average size of the ozone hole was 7.23 million square miles. This seasonal window is typically when extremely cold temperatures, polar stratospheric clouds, and sunlight-driven chemical reactions combine to create the most severe ozone thinning over Antarctica. After this period ends, the ozone layer gradually begins to strengthen again as temperatures rise and atmospheric circulation changes.

Paul Newman, senior scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and leader of NASA’s ozone research team, explained that the 2025 data is consistent with long-term recovery projections. According to Newman, ozone holes during the early 2000s were significantly larger and more persistent. Today, however, they are generally forming later in the season and breaking up earlier — another sign of continuing atmospheric improvement. He noted, however, that restoration is not yet complete: “We still have a long way to go before the ozone layer returns to the levels we saw in the 1980s.”

Indeed, this year’s ozone hole began to break apart nearly three weeks earlier than the average breakup time over the past decade, demonstrating yet another encouraging pattern. Early breakup is important because it reduces the length of time during which harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation can potentially reach higher levels at the surface in southern regions.

NOAA scientist Stephen Montzka further emphasized the progress by explaining that levels of ozone-depleting substances in the Antarctic stratosphere have fallen by about one-third compared to their peak around the year 2000. This decline directly results from the Montreal Protocol, the landmark 1987 global agreement to phase out chemicals such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), halons, and other compounds once widely used in aerosol sprays, foam production, air conditioners, refrigerators, and industrial applications. These chemicals break apart ozone molecules once they are exposed to UV radiation in the upper atmosphere, creating long-lasting damage.

Montzka and other experts point out that while atmospheric chlorine and bromine concentrations remain elevated, they are slowly but steadily decreasing thanks to decades of coordinated action by nearly every country in the world. If these reductions continue at their expected pace, most scientists project that the Antarctic ozone layer could fully recover later this century, though precise timelines may vary depending on natural atmospheric variability and how climate change affects stratospheric temperatures.

Newman also noted that if the atmosphere still contained the same amount of chlorine as it did 25 years ago, this year’s ozone hole would have been more than one million square miles larger. This dramatic difference illustrates how powerful ozone-depleting chemicals once were — and how effective the global ban has been in reversing the damage.

The ozone layer itself sits between roughly 7 and 31 miles above Earth’s surface, forming a protective shield that absorbs much of the Sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation. Without this natural barrier, UV exposure on Earth would rise dramatically, increasing risks such as skin cancer, cataracts, weakened immune systems, reduced crop yields, and harm to sensitive marine organisms like phytoplankton.

Ozone depletion occurs when human-made compounds containing chlorine or bromine rise into the stratosphere and are broken apart by solar radiation. Once released, these atoms trigger chain reactions that destroy large quantities of ozone. Although these substances were widely used for decades, the Montreal Protocol successfully eliminated most production and consumption of these chemicals worldwide — often cited as one of the most successful environmental agreements in history.

Despite the progress, scientists stress that monitoring must continue. Recovery is slow because many ozone-depleting substances remain in the atmosphere for decades. The Antarctic ozone hole will continue to appear each year until chlorine and bromine levels drop low enough for the ozone layer to sustain itself without major seasonal thinning. Additionally, volcanic eruptions, large wildfires, and shifts in atmospheric dynamics associated with climate change can temporarily influence ozone concentrations, making consistent long-term measurements essential.

Still, the 2025 findings add to a growing body of evidence showing that global environmental cooperation can lead to real, measurable change. The shrinking ozone hole demonstrates that science-based policy, international coordination, and long-term commitments can help restore vital Earth systems — offering a hopeful model for addressing other environmental challenges.