The Venezuela Oil Market Recovery 2026 is underway, marking a decisive shift following the dramatic ouster of Nicolás Maduro by U.S. forces on January 3, 2026. While the global energy market expected a long, painful pause, and analysts predicted months of legal wrangling before a single drop of oil moved, they were wrong.

In a move that prioritizes pragmatism over perfection, the U.S. interim administration has handed the keys of Venezuela’s oil trade to the “SWAT teams” of the commodity world: Vitol and Trafigura. This analysis explores the depth of this strategic shift, the operational nightmare these traders face, and why the U.S. chose agile traders over lumbering oil majors to resuscitate a collapsed economy.

Key Takeaways

- Strategic Shift: The U.S. prioritized “Fast Cash” by licensing traders (Vitol/Trafigura) over “Slow Rebuild” (Big Oil) to stabilize the post-Maduro transition immediately.

- Logistics are King: The operation relies on importing Naphtha (via Vitol) to dilute heavy crude so it can flow through neglected pipelines.

- Geopolitical Win: China and India are being reintegrated into the market as customers, but under a U.S.-controlled financial framework.

- The “Lockbox”: Oil revenue is not going to the Venezuelan government directly but to U.S.-monitored escrow accounts to prevent corruption.

- Fragility: The entire recovery rests on “rotting” infrastructure that faces high risks of environmental failure or sabotage.

Awakening the Rust Belt: The Scene at Jose

On the scorching docks of the Jose Terminal, located on the Caribbean coast of Venezuela, the air smells of salt, sulfur, and something that hasn’t been felt here in nearly a decade: opportunity. For years, this terminal, once the beating heart of Latin America’s wealthiest nation, sat largely dormant. The pipes rusted, the storage tanks corroded, and the workers fled.

But this week, the silence was broken not by the rhetoric of a dictator, but by the deep, mechanical hum of a supertanker’s engines. The Trafigura-chartered vessel, a massive crude carrier, began loading 2 million barrels of heavy Merey crude. This is the visible face of the “Return of the Giants.”

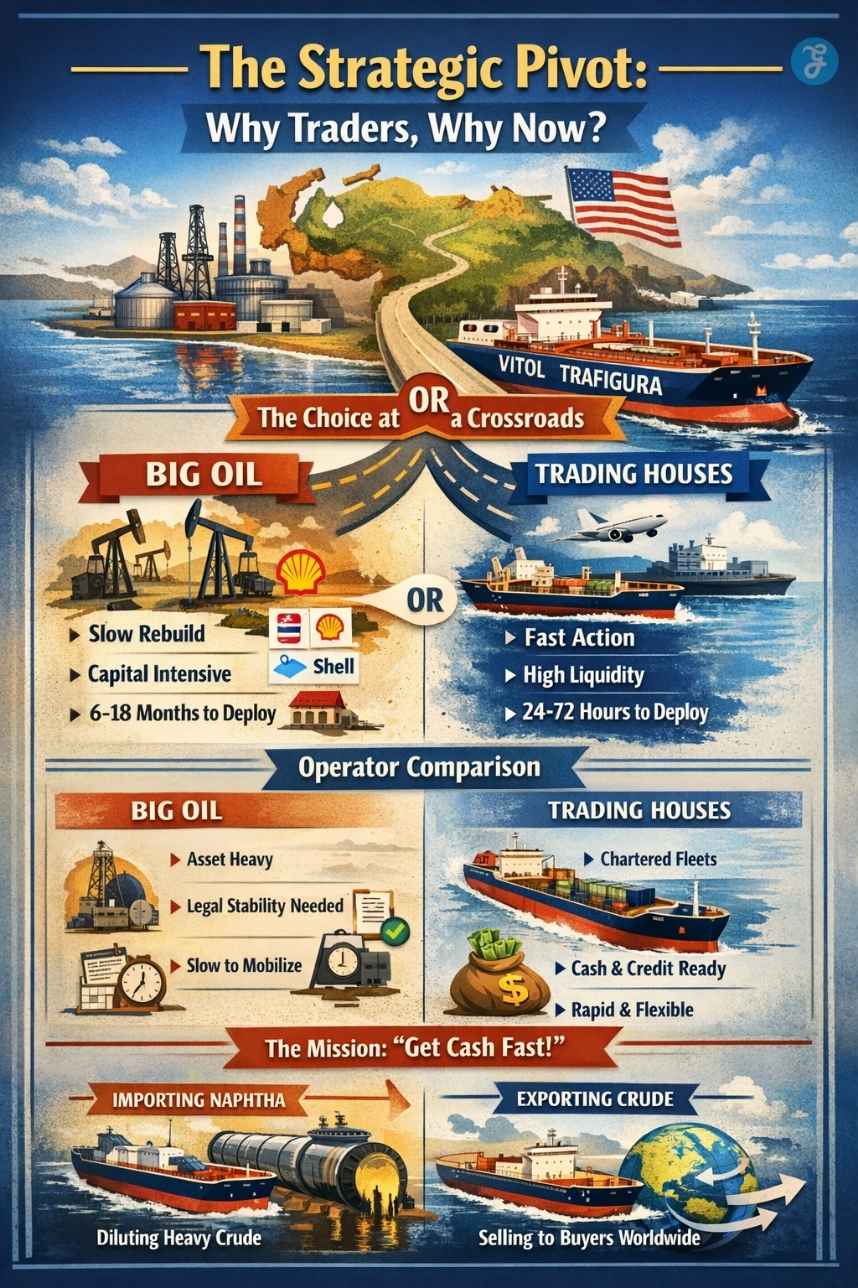

The Strategic Pivot: Why Traders, Why Now?

To understand the magnitude of this news, one must first understand the vacuum left by the Maduro regime. PDVSA (Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A.) is not just broke; it is structurally broken. It has no credit lines, no insurance, and a fleet of tankers that are largely unseaworthy.

When the dust settled in Caracas earlier this month, the U.S. Treasury and the new Interim Council faced a critical dilemma:

- Wait for Big Oil (Exxon, Chevron, Shell): These companies have the capital to rebuild, but they move slowly. They demand legal immunity, long-term stability, and to pass legislation before deploying assets. That takes years.

- Unleash the Traders (Vitol, Trafigura, Glencore): These firms are logistics experts. They don’t drill for oil; they move it. They are comfortable with risk, have massive liquidity, and can charter independent fleets within hours.

The choice was clear. The country needs cash now for food, medicine, and payroll. You cannot eat oil; you must sell it first.

The “Paramedic” Approach

Think of Vitol and Trafigura not as the doctors who will cure Venezuela’s long-term cancer, but as the paramedics arriving at the scene of the crash. Their job is to stop the bleeding and get the circulation moving.

“The majors [Big Oil] want a constitution. The traders just want a contract,” notes Dr. Elena Rodriguez, a senior energy analyst at the Caracas Energy Institute. “The U.S. realized that if it waited for Exxon to feel comfortable, the interim government would run out of cash by February. Vitol was ready to load by Tuesday.”

The Operator Comparison [Big Oil vs. Traders]

| Feature | Big Oil (Exxon, Chevron, etc.) | Trading Houses (Vitol, Trafigura) |

| Primary Goal | Reserve booking & long-term production | Arbitrage, logistics, & immediate cash flow |

| Risk Tolerance | Low (Requires legal stability) | High (Thrives in volatility) |

| Speed of Entry | 6-18 Months | 24-72 Hours |

| Asset Heavy? | Yes (Rigs, Refineries) | No (Chartered ships, leased storage) |

| Role in Venezuela | Phase 2: Reconstruction (2027+) | Phase 1: Stabilization (2026) |

The “Plumbing” Crisis: Diluents and Decay

The most underreported aspect of this story is the technical nightmare of Venezuelan geology. Venezuela sits on the world’s largest oil reserves, but it is mostly extra-heavy crude. It has the consistency of peanut butter. It cannot flow through pipelines at normal temperatures unless it is diluted.

Under Maduro, the domestic production of diluents (like Naphtha) collapsed. PDVSA began relying on opaque swaps with Iran to keep the oil flowing, often resulting in poor quality blends that damaged refineries.

Vitol’s Critical Role: The Naphtha Lifeline

Vitol’s first move wasn’t to take oil out, but to bring liquid in.

- The Shipment: On January 10, a Vitol-chartered vessel docked at Jose carrying 500,000 barrels of heavy naphtha from the U.S. Gulf Coast.

- The Chemistry: This naphtha is injected into the wells and pipelines in the Orinoco Belt. It mixes with the sludge-like crude, reducing its viscosity so it can be pumped 200 miles to the coast for export.

- The Implication: Without this shipment, production would physically halt within days due to pipeline clogging. Vitol is effectively supplying the blood thinners for the country’s circulatory system.

Trafigura’s Role: The Floating Supply Chain

While Vitol handles the input, Trafigura is managing the output. The onshore storage tanks in Venezuela are reportedly full to the brim, not because production is high, but because exports stopped.

Trafigura is employing a strategy known as Floating Storage:

- They charter Massive Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCCs).

- They load the oil from the onshore tanks onto these ships.

- The ships move to international waters.

- This immediately frees up space in the onshore tanks, allowing the wells to keep pumping.

It is a logistical ballet performed on high seas, requiring immense coordination and credit lines that only firms like Trafigura possess.

The Gasoline Paradox: Exporting Crude, Importing Stability

While Trafigura tankers are busy loading crude for export, a different fleet is quietly docking at the Guaraguao terminal: gasoline tankers. This creates a bitter paradox for the Venezuelan people: the country with the world’s largest oil reserves is currently unable to fuel its own cars.

- The Refinery Collapse: Venezuela’s domestic refining capacity (1.3 million bpd on paper, primarily at the Paraguaná Refining Center) is effectively dead. Years of cannibalizing parts and a lack of skilled maintenance have left the Cardón and Amuay refineries operating at less than 10% capacity.

- Vitol’s Dual Role: Vitol is not just exporting crude; it is executing a “survival swap.” A portion of the crude export revenue is being immediately used to purchase finished gasoline and diesel from the U.S. and Europe to be shipped back to Venezuela.

- Why this matters: The interim government knows that while crude exports pay the debt, gasoline availability prevents riots. If the pumps run dry in Caracas, the fragile political stability could collapse overnight. The traders are effectively managing the country’s social peace through fuel logistics.

Geopolitics: The New Map of Influence

The re-entry of these giants is not just a commercial transaction; it is a geopolitical masterstroke by Washington. By licensing Western-compliant traders to handle the oil, the U.S. has effectively seized control of Venezuela’s revenue stream without formally nationalizing it.

Neutralizing the “China Problem”

For a decade, China was the primary financial backer of the Maduro regime, accepting oil as repayment for billions in loans. There were fears that Beijing would be hostile to the new U.S.-backed government.

However, pragmatism reigns in Beijing too.

- The Pivot: Chinese state refiners (Sinopec, PetroChina) are oil-thirsty. They have refineries specifically designed for heavy Venezuelan crude.

- The Deal: Instead of buying from a sanctioned, erratic PDVSA, China is now buying the same Venezuelan oil from Trafigura.

- Why it works: It “launders” the political risk. China gets its energy security; the U.S. ensures the money goes into transparent accounts rather than Maduro’s pockets. It is a rare win-win in the tense U.S.-China relationship.

The Russian “No-Go” Zones

While Chinese companies have pivoted to buying from Trafigura, the massive Russian energy footprint in Venezuela remains a toxic asset.

- The Roszarubezhneft Problem: In November 2025, the Maduro regime hastily extended joint venture contracts with Roszarubezhneft (the Russian state entity that absorbed Rosneft’s Venezuelan assets) through 2041.

- The Quarantine: Under the new U.S. guidance, these specific oil fields, primarily in the Petromonagas and Petroperijá blocks, have been “quarantined.” Trafigura and Vitol have been instructed to strictly avoid marketing any crude originating from these Russian-operated fields to avoid triggering secondary sanctions or diplomatic standoffs with Moscow.

- The Result: This creates a “Swiss Cheese” map of production. The U.S. traders are lifting oil from former Western/PDVSA fields, while the Russian fields sit idle, their storage tanks filling up with nowhere to go, a strategic squeeze designed to force a Russian exit without a direct military confrontation.

India’s Return

India, previously a top buyer, was forced out by sanctions in 2019-2020.

- Reliance Industries and Nayara Energy operate some of the most complex refineries in the world (e.g., Jamnagar). They thrive on cheap, heavy, “dirty” oil, which they turn into high-quality diesel.

- With Vitol acting as the middleman, Indian companies can resume purchases without fear of violating U.S. sanctions (since the U.S. issued the license). This reconnects Venezuela to its most natural market.

Key Export Destinations [Jan-Mar 2026 Forecast]

| Destination | Primary Buyer(s) | Volume (Barrels/Day) | Strategic Note |

| United States | Valero, Chevron (Pascagoula) | 300,000 | Replacing Russian/Iraqi heavy imports |

| India | Reliance, Nayara | 450,000 | High complexity refining capacity |

| China | PetroChina | 250,000 | Paying down legacy debt via a new mechanism |

| Europe | Repsol, Eni | 150,000 | “Oil-for-Debt” swap continuation |

The Economics of the “Special License”

Why is the U.S. allowing this? The “Special License” granted to Vitol and Trafigura comes with strict strings attached. This is not a free market bonanza; it is a controlled demolition of the old, corrupt system.

The Escrow Model

In the past, when PDVSA sold oil, the money went to the Central Bank of Venezuela, where it often disappeared.

Under the new January 2026 framework:

- Trafigura sells the cargo to a refiner (e.g., Valero in Texas).

- Valero pays Trafigura.

- Trafigura deducts its fee and logistical costs (shipping, insurance).

- The Balance is deposited directly into a U.S.-supervised Escrow Account at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

This is the crucial detail. The interim Venezuelan government does not touch the cash directly. They must submit “withdrawal requests” for approved projects: humanitarian aid, power grid repairs, and civil servant salaries. This mechanism effectively prevents graft and ensures the “oil money” actually reaches the populace.

Addressing the Debt Mountain

Venezuela owes approximately $150 billion to creditors. These bondholders have been circling like sharks. The entry of reputable traders is the first signal to the bond market that there is a path to repayment.

- By regularizing exports, the value of Venezuelan sovereign bonds has jumped 400% in trading this week (from 2 cents on the dollar to 8 cents).

- The logic is simple: A producing Venezuela can pay; a collapsed Venezuela cannot.

The Risks: A House of Cards?

While the “Return of the Giants” is being hailed as a success, the situation is incredibly fragile. The reliance on trading houses introduces specific risks that cannot be ignored.

1. The Environmental Time Bomb

The infrastructure is in worse shape than satellite images suggested.

- Spill Risk: The pipelines connecting the Orinoco Belt to the coast are corroded. Increasing pressure to pump 1 million barrels a day risks catastrophic ruptures.

- The “Rust” Factor: The loading arms at the Jose terminal are rusted. If a loading arm snaps while connected to a Trafigura tanker, it could dump thousands of barrels into the Caribbean. The traders are reportedly bringing in their own safety crews, but they are working with compromised hardware.

2. Corporate Dependency

Critics argue that Venezuela is trading a political dictatorship for a corporate oligarchy.

- By relying on Vitol and Trafigura, the interim government is handing immense leverage to two private, foreign companies.

- If Trafigura decides the margins aren’t high enough and pulls out, the economy crashes again. Venezuela has no “Plan B” until the major oil companies return, which is years away.

3. The Shadow of Sabotage

Remnants of the Maduro regime, including armed paramilitaries (colectivos), still operate in the interior of the country.

- Pipelines are soft targets. A single well-placed explosive on the main pipeline to Jose would halt the entire Vitol-Trafigura operation.

- The U.S. military is providing security at the ports, but the thousands of miles of pipeline through the jungle are largely undefended.

The Human Bottleneck: Can the Diaspora Return?

The biggest constraint on Venezuela’s recovery is not capital, but talent. Following the 2002-2003 strikes, the Chavez government fired over 18,000 highly skilled PDVSA employees (the Gente del Petróleo), sparking a massive brain drain to Calgary, Houston, and Bogota.

- The Safety Trap: While headhunters are frantically contacting Venezuelan engineers in Texas and Alberta, many are refusing to return. The “rotting” infrastructure poses lethal risks to workers—from gas leaks to structural failures.

- The Knowledge Gap: The current PDVSA workforce is largely military-led and inexperienced. Without the return of the “diaspora experts” who understand the unique, complex geology of the Orinoco Belt, Vitol and Trafigura are flying blind.

- The Interim Solution: To bypass this, the trading houses are deploying their own “fly-in, fly-out” technical squads—mercenary engineers on high-hazard pay contracts—to oversee critical loading operations, treating the oil terminals more like offshore rigs than sovereign soil.

Future Outlook: The Bridge to 2027

The entry of Vitol and Trafigura is not the endgame; it is the bridge.

The U.S. strategy is clear:

- Phase 1 (2026): Use traders to maximize cash flow using existing (rotting) infrastructure. Stabilize the currency and feed the population.

- Phase 2 (2027-2030): Once the country is stable and a new legal framework is passed, invite Chevron, Exxon, and Shell to invest the $100 billion needed to actually fix the industry.

For now, the world is watching the Jose Terminal. Every tanker that leaves is a small victory. Every dollar that lands in the Federal Reserve escrow account is a lifeline.

The Giants have returned. They are not the saviors Venezuela dreamed of, but they are the saviors Venezuela needs right now. They bring with them the cold, hard efficiency of the market—a sharp contrast to twenty years of ideology. For a country on its knees, efficiency is the only hope left.

Final Thought: The Art of the Possible

Politics is often about ideals; energy is about physics and finance. The decision to license Vitol and Trafigura acknowledges a harsh reality: you cannot rebuild a nation on promises. You need diesel to run the trucks that carry the food. You need revenue to pay the doctors.

By deputizing the world’s most aggressive capitalists to save a socialist ruin, the post-Maduro administration has made a deal with the devil, or perhaps, a deal with the only entities capable of navigating the hell that Venezuela became. As the first Trafigura tanker disappears over the horizon, it carries more than just oil; it carries the fragile promise of a normal life for 28 million people.