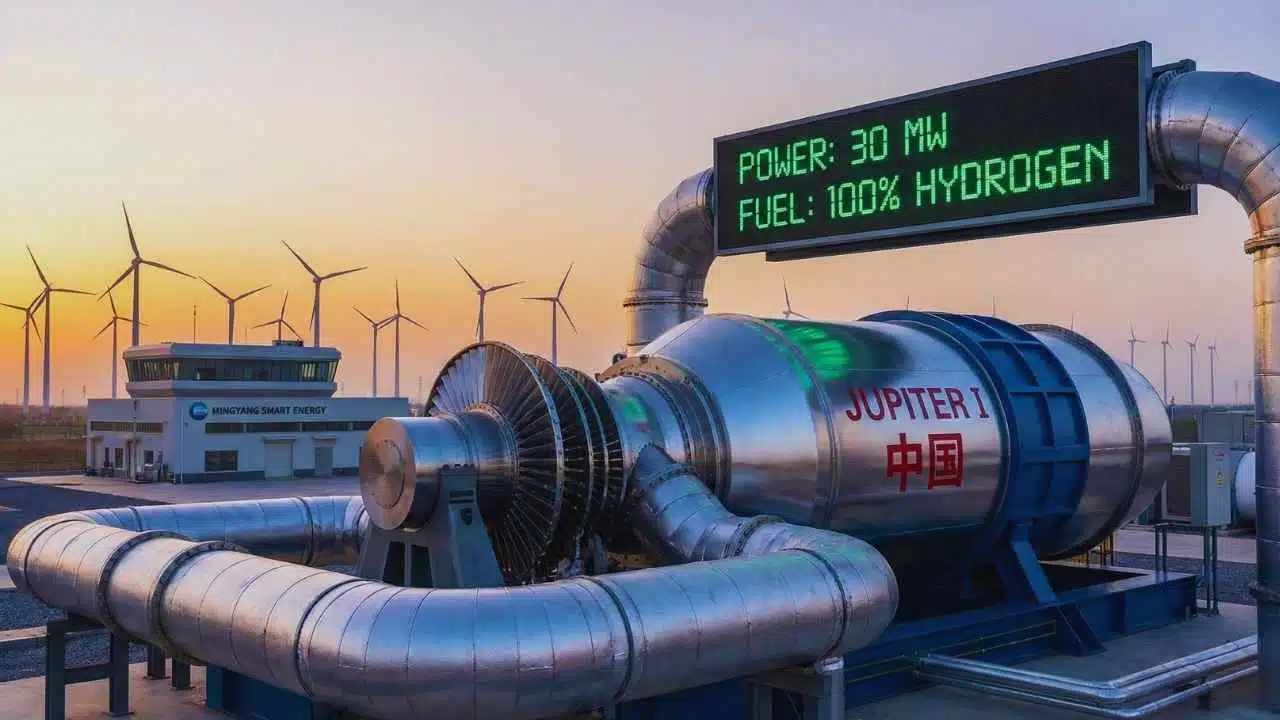

China has started building a 30MW pure hydrogen gas turbine and hydrogen storage demonstration project in Ordos, Inner Mongolia, aiming to turn surplus wind and solar power into stored hydrogen and convert it back into electricity during peak demand.

What the project is and why it matters now?

The project is being built in the Otog (Etuoke) High-Tech Industrial Development Zone in Ordos, a major energy hub in north China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. Local announcements describe it as the world’s first demonstration project that combines a 30MW-class pure hydrogen gas turbine with a hydrogen-based energy storage system designed for grid support.

The basic promise is straightforward: hydrogen can act like a “storage tank” for renewable electricity that would otherwise be wasted. In areas with huge wind and solar output, power can spike at midday or during strong winds and fall sharply when weather changes. A grid needs tools that can absorb excess electricity and return power later, especially during evening peaks.

Batteries can help, but long-duration needs—multi-hour to multi-day balancing—become more difficult and expensive at very large scale. Supporters of hydrogen storage argue it can store more energy for longer periods and can be built near renewable bases where land and resources are available.

For China, this is also about industrial capability. A pure hydrogen turbine is a complex piece of equipment with demanding safety and combustion requirements. Moving from lab tests to a working grid-scale site signals an attempt to prove the technology is ready for real-world operation, not just controlled demonstrations.

The project is closely tied to a broader clean-energy buildout in Inner Mongolia and Ordos. Ordos has been promoting large renewable projects in desert and semi-arid areas, with rapid capacity additions and new grid infrastructure. That environment makes it a logical testbed for large “renewables + storage” experiments.

How the electricity–hydrogen–electricity system works?

This project is designed around a closed-loop idea: electricity → hydrogen → electricity. The steps look like this:

- Step 1: Capture surplus renewable power. When wind and solar generation exceed demand or grid export capacity, excess electricity can be directed away from curtailment.

- Step 2: Make hydrogen through electrolysis. Electrolyzers use electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen.

- Step 3: Store hydrogen. Hydrogen can be stored in pressurized tanks and managed as an energy reserve.

- Step 4: Generate electricity on demand. A pure hydrogen gas turbine burns hydrogen to spin a turbine and produce electricity when the grid needs it most.

Project details released publicly include a reported hydrogen production capacity of 48,000 Nm³ per hour, indicating that the site is intended to handle large, industrial-scale flows rather than small pilot volumes.

A key point: this approach is not only about making “green hydrogen.” It’s about using hydrogen as energy storage—a buffer that can smooth renewable variability and provide dispatchable power output when demand rises.

Key reported technical details

| Component | Reported scale or role | What it’s intended to do |

| Pure hydrogen gas turbine | 30MW-class | Convert stored hydrogen into electricity for peak demand support |

| Hydrogen production | 48,000 Nm³/hour | Convert surplus renewable electricity into hydrogen |

| Storage + generation model | Hydrogen-based long-duration storage | Shift renewable electricity from off-peak periods to peak periods |

| Site location | Otog (Etuoke), Ordos, Inner Mongolia | Demonstrate the model near major wind/solar resources |

Timeline of major milestones

| Date | Milestone | What it signals |

| Dec 2024 | 30MW-class pure hydrogen turbine ignition reported | First major “system-level” validation step |

| Aug 8, 2025 | Construction start reported in Ordos | Move from prototype milestone to site buildout |

| Mid-Aug 2025 | Turbine shipment to project site reported | Equipment delivery for installation and commissioning phase |

| Late 2025 (target) | Demonstration/commissioning goal stated in project materials | Planned window for proving stable operation at scale |

The turbine technology: what makes “pure hydrogen” different?

A hydrogen turbine is not just a gas turbine with a different fuel. Hydrogen has combustion characteristics that create design and control challenges, particularly at high power output:

- Hydrogen burns faster than natural gas. Faster flame speeds can raise the risk of flame instability if the combustor is not designed for it.

- Flashback risk is higher. The flame can move backward into parts of the combustor where it should not be, creating safety hazards.

- Combustion oscillations can damage hardware. Pressure fluctuations can stress components and reduce reliability if not controlled.

- NOx emissions still matter. Burning hydrogen produces no carbon dioxide at the point of generation, but high-temperature combustion can still create nitrogen oxides (NOx), which must be managed through combustor design and operating strategy.

Public descriptions of the turbine development emphasize that the system had to solve stability and safety challenges before moving toward deployment. Reports also describe advanced manufacturing methods being used for critical combustor components, including additive manufacturing approaches aimed at improving precision and integration.

This matters because the headline claim—“pure hydrogen”—is stronger than “hydrogen blending.” Many turbines worldwide are moving step-by-step: first allowing small hydrogen blends, then higher blends, and only later targeting 100% hydrogen capability. A pure hydrogen turbine is a higher bar because it must run across a range of loads and conditions without the stabilizing effect of methane in the fuel mix.

Why a 30MW-class demonstration is a big step?

A 30MW unit is large enough to be meaningful for a grid and for industrial planning. It also forces tough questions that small tests can avoid:

- Can the turbine ramp up and down smoothly without instability?

- Can it maintain performance during long operating hours?

- How do operators manage startup, shutdown, and emergency procedures safely?

- What maintenance cycles and parts lifetimes look like under hydrogen combustion?

A demonstration project is where these questions move from theory to operating data. If the turbine runs reliably, it can support future projects. If it struggles, it still provides lessons—but it may slow down broader rollout.

Why Inner Mongolia is the test ground?

Inner Mongolia has some of China’s strongest wind and solar resources and has been expanding renewables at speed. Ordos, in particular, has positioned itself as a center for large-scale energy projects, including desert-based solar developments and major wind bases.

Local development statements have highlighted Ordos’ strong renewable conditions, including large solar irradiation and major wind resources. The region has also been building the industrial ecosystem needed for large energy projects: manufacturing, heavy transport capacity, and grid connections.

This context matters because hydrogen energy storage is easiest to justify where there is a combination of:

- Huge renewable output

- Periods of surplus electricity

- A need for flexible, dispatchable power

- Space and infrastructure for storage and heavy equipment

- Policy support and pilot-project appetite

The Ordos hydrogen turbine project is being framed as a model that could be replicated in other renewable bases. If that happens, Inner Mongolia’s role could expand from being a generator of wind/solar electricity to also being a producer and user of hydrogen as an energy carrier.

Where this fits in China’s broader hydrogen and grid push?

China has laid out national-level goals for hydrogen development through a medium- and long-term plan covering 2021–2035. That plan sets the direction for building industrial capability, improving core technologies, and expanding hydrogen applications over time.

At the same time, China’s grid planning has been focused on flexibility: building and upgrading storage, improving power system responsiveness, and integrating growing wind/solar shares without compromising reliability. Hydrogen storage projects are one of several options being explored alongside pumped hydro, batteries, and flexible thermal generation upgrades.

In this environment, the Ordos project can be seen as both a technology demonstration and a policy-aligned experiment: it tests whether hydrogen can become a practical part of the “flexible grid toolkit” as renewables scale further.

What to watch next and what success would look like?

A groundbreaking ceremony and a shipped turbine are important milestones, but the real test is what happens after installation. Several outcomes will determine how the industry interprets this project.

Operational performance and grid value

Success will depend on whether the system can deliver electricity when needed, repeatedly, and safely. Grid operators typically care about:

- Reliability during peak-demand dispatch

- Ramp rate and responsiveness

- Ability to run at partial load without instability

- Predictable maintenance and downtime

If the system performs well, it could strengthen the case for hydrogen-based storage in high-renewables regions. If performance is inconsistent, the project may remain a one-off demonstration rather than a template.

Cost, efficiency, and real-world utilization

Hydrogen storage systems involve multiple stages—electricity conversion to hydrogen, compression and storage, and conversion back to electricity—each with losses and costs. Whether the project expands will likely depend on practical economics:

- Access to low-cost surplus renewable electricity

- The value of peak power delivered to the grid

- Policy incentives for long-duration storage and low-carbon capacity

- Equipment costs for electrolyzers, storage, and turbine hardware

Even if hydrogen-to-power is not the cheapest option in every location, it may be attractive where long-duration storage is critical and large renewable curtailment is common.

Safety systems and permitting

Hydrogen is a clean fuel, but it demands careful safety design. Operators typically focus on:

- Leak detection and ventilation systems

- Materials choices to reduce hydrogen embrittlement risks

- Safe storage layout and separation distances

- Emergency shutdown protocols and staff training

If the project builds a strong safety record and clear operating procedures, it could help set standards for future sites.

Global significance: what this adds to international progress?

Around the world, hydrogen turbines have been tested in various forms, including industrial demonstrations that use renewable hydrogen in integrated systems. What makes the Ordos project stand out is the claim of combining pure hydrogen combustion with a 30MW-class turbine as part of a purpose-built storage demonstration site.

If the late-2025 commissioning goals are met and operating results are shared, the project could become one of the most closely watched hydrogen-to-power demonstrations globally. If it succeeds, the next phase could be scaling the concept in other renewable bases and connecting hydrogen storage more directly to grid planning.