Dhaka has always been a city that remembers in layers—through lanes and rooftops, through rivers of traffic, through the way crowds gather without needing an invitation. But there are a few dates that sit deeper than memory, dates that feel stitched into the city’s concrete. 16 December 1971 is one of them.

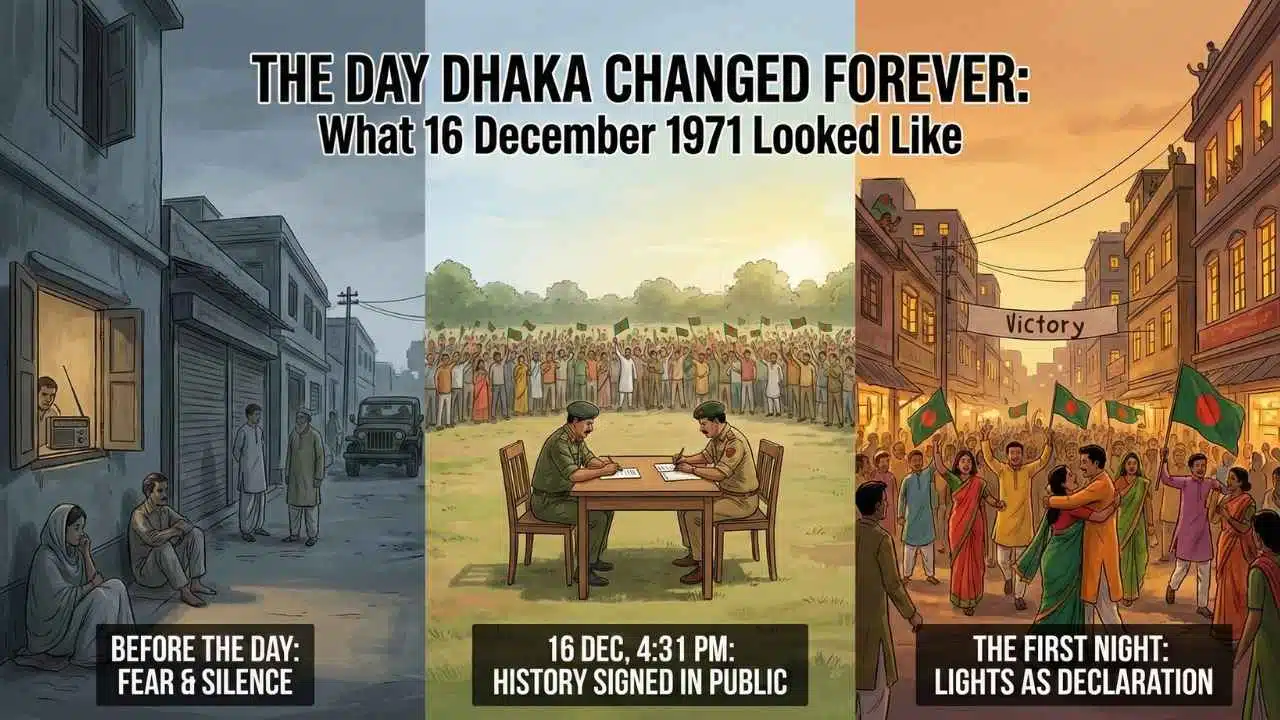

On that day, Dhaka didn’t “change” the way cities usually change—slowly, over years, through new buildings and new roads. It changed in a matter of hours. The same streets that had carried fear and silence began to carry voices again. The same windows that had stayed cautious and dark began to glow.

People who had learned to whisper leaned closer to radios, then climbed up to rooftops, then finally stepped outside—because the sky, the rumors, and the movement all pointed to something the heart wanted to believe but the mind still questioned: is it really happening?

This is not a slogan-filled retelling. It’s a carefully researched reconstruction of what that day looked and felt like, drawn from credible histories, primary documentation, and eyewitness accounts. We follow Dhaka from the tense days of curfew and radio whispers, through the unmistakable signs of surrender, to the open ground where history was signed in public—and into the first night when light itself became a declaration that the city was no longer living under fear.

Before the Day: Why Dhaka’s “Victory” Was Also a Release

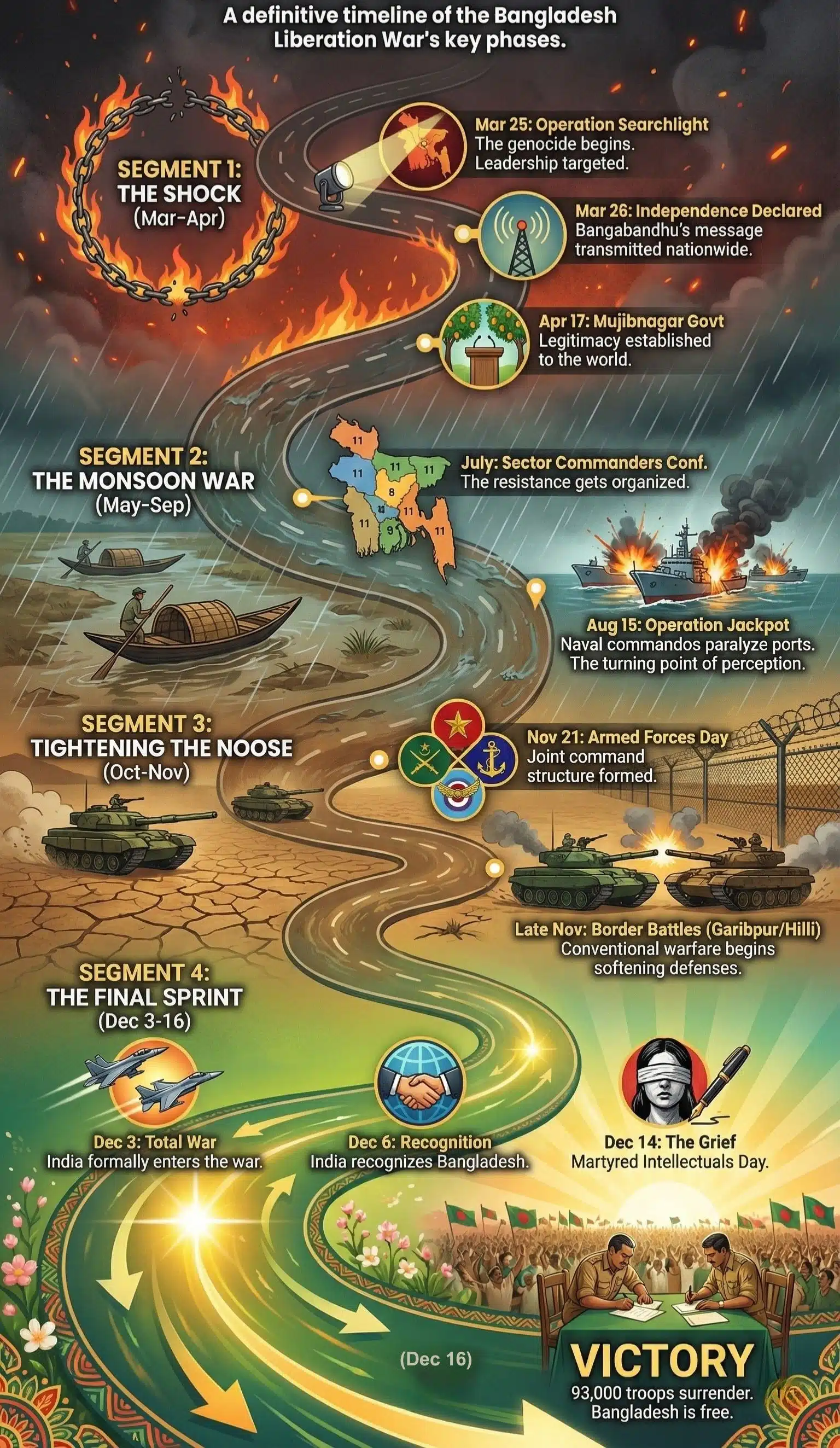

To understand the force of 16 December, you have to remember what Dhaka had been since late March.

On the night of 25 March 1971, the Pakistan Army launched a crackdown widely known as Operation Searchlight. Dhaka became a city where people learned quickly that the wrong movement, the wrong sentence, or the wrong association could be fatal. The months that followed reshaped daily life into survival routines: curfews, disruptions, uncertainty, whispers, and a constant sense that danger could arrive without warning.

Even for those not directly targeted, the atmosphere changed the city’s rhythm. Dhaka is normally loud—markets, rickshaws, and conversations spill onto streets. Under occupation, loudness becomes a risk.

By December, the endgame was visible. Battles were not only happening “somewhere far away.” Events were tightening around the capital. When the conflict expanded into the India–Pakistan War of 1971 in early December, the fall of the Pakistani position in East Pakistan accelerated rapidly. Dhaka was no longer a distant administrative center; it was the place where the war’s final signature would land.

Dhaka in the Days Leading Up to 16 December: Curfew, Rumors, and Radio

By the second week of December, many residents sensed the end approaching—but sensing is not the same as believing.

In the days before surrender, Dhaka experienced restrictions that kept people indoors. Curfews and heavy control of movement created the feeling of a city forced into silence at the very moment history was about to burst it open.

Inside homes, radios mattered. People listened carefully—often secretly—to broadcasts that suggested the Pakistani position was collapsing and surrender might be near. But hope had been punished too often. Even when the news sounded clear, many still held back emotionally. A rumor can get you killed under an occupation; it can also break your heart if you trust it too quickly.

So the city waited in a strange state: half-celebration in the mind, half-fear in the body.

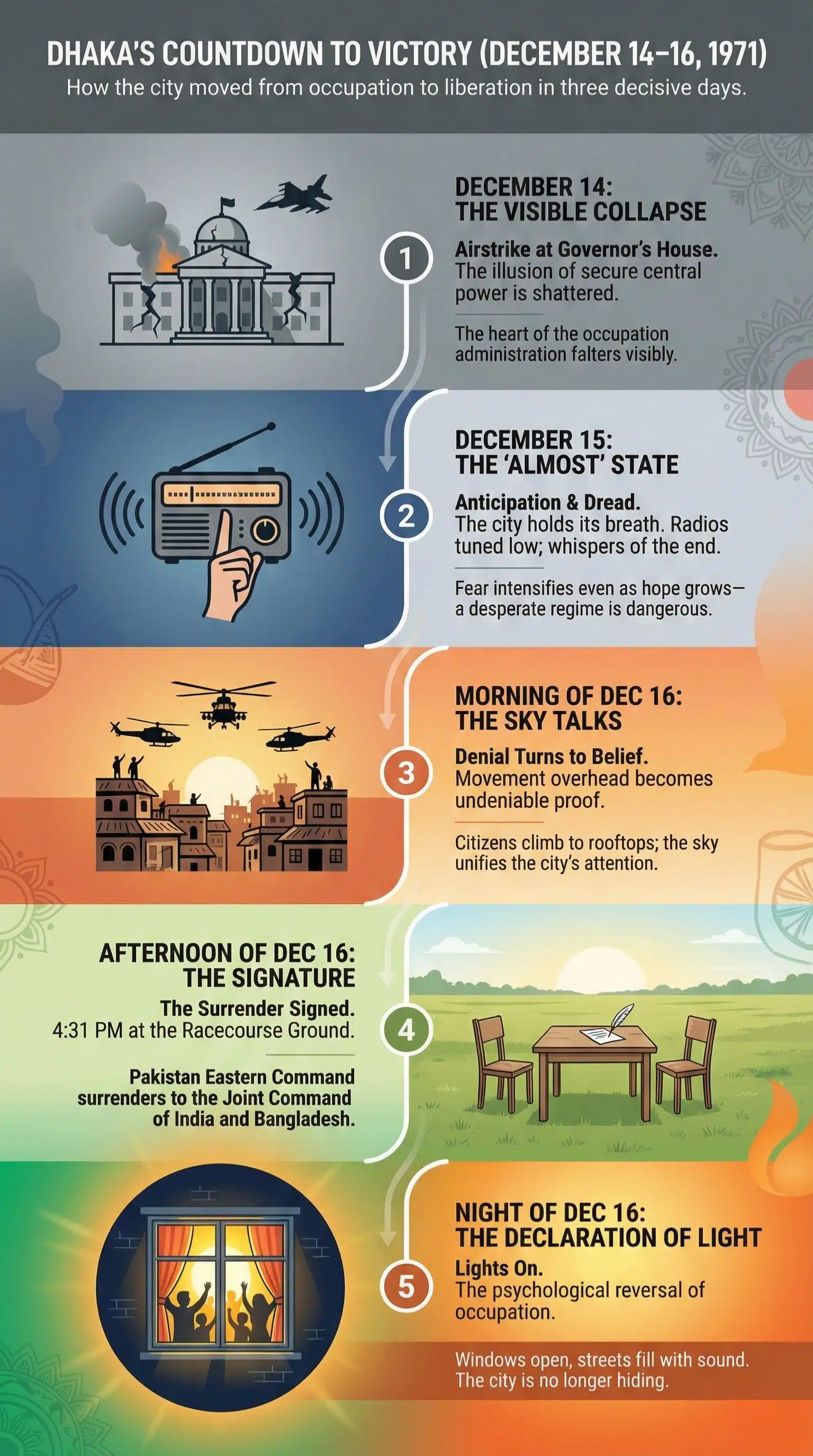

14 December: When the Collapse Became Visible

Two days before Victory Day, a dramatic moment signaled to many that the authorities in Dhaka were losing control.

At the Governor’s House, a meeting was underway—an attempt to govern amid a collapsing front. Then came an airstrike. The incident didn’t just damage a building; it damaged the illusion that the capital was secure. When leadership falters in the center of a capital city, people feel it even if they are miles away. It travels through rumor and tightened security, through sudden urgency in official behavior.

Reports describe the governor resigning and relocating to the Intercontinental Hotel—another signal that the structure of power was shifting, and that the people inside the system were trying to protect themselves as the system fell apart.

That same day is also remembered for a different horror: the targeted killing of Bengali intellectuals. While this article focuses on 16 December, the emotional geography of Dhaka cannot separate the joy of victory from the grief that surrounded it. In many families, the period between 14 and 16 December was not a clean arc from darkness to light. It was darkness, deeper darkness, and then the sudden opening of a door—without the lost returning through it.

15 December: The City Holds Its Breath

By 15 December, Dhaka was living in “almost.” Almost free. Almost over. Almost safe. Almost.

People’s behavior becomes cautious in the final days of a collapsing regime because collapse can be violent. Fear doesn’t vanish simply because hope increases; often fear intensifies because the desperate can do desperate things.

Inside many homes, the same ritual was repeated: someone turning the radio down low, someone else watching the window, and conversations that ended mid-sentence whenever footsteps sounded outside.

If you want to picture Dhaka on 15 December, picture a city where anticipation and dread shared the same room.

Morning of 16 December: The Sky Starts Talking

For a lot of Dhaka residents, the first undeniable sign didn’t arrive as a formal statement. It arrived as movement overhead.

Helicopters became a language: fast, unmistakable, and hard to dismiss as rumor. People who had been stuck indoors for days climbed to rooftops, leaned into courtyards, peered from windows, and pointed upward.

The sky can unify a city’s attention in a way newspapers never can. When the same aircraft passes over multiple neighborhoods, everyone receives the same message at the same time: something is changing, and it is happening now.

But even then, disbelief lingered. After months of occupation, people were trained—by experience—to doubt good news until it stood on the street in daylight.

So Dhaka moved through the morning and toward midday like someone walking toward a truth they are afraid to touch.

Behind the Scenes: Tejgaon, Headquarters, and the Machinery of Surrender

While the city watched the sky, the surrender process required fast and careful coordination—documents, meetings, commanders, and a controlled transfer of authority.

Reports of the surrender timeline describe key movements through Tejgaon Airport and the East Pakistan military headquarters. Senior officers and representatives moved into position. The surrender instrument had to be presented, reviewed, and signed. The scene, from a distance, may have looked like “things happening quickly.” Up close, it was a precise set of steps meant to end organized fighting and prevent more loss of life.

This detail matters for a long-form retelling because it prevents the day from becoming mythology. The liberation of Dhaka was not only an emotional turning point—it was also an administrative and military transition, formalized through documented procedures.

And yet, the emotional and the procedural met in one iconic place.

The Racecourse Ground: Where a City Became a Witness

The surrender ceremony took place at the Ramna Racecourse Ground—today known as Suhrawardy Udyan. That location matters because it wasn’t secluded. It wasn’t hidden inside a building. It was open, public, and central—meaning the people, not just officials, could feel like witnesses to history.

One of the most haunting details in accounts of that day is how ordinary the physical setup was. Not a grand stage. Not an ornate hall. Just the essentials: a table, two chairs, and a document that would redraw the map of South Asia.

The simplicity of the furniture throws the magnitude of the moment into sharper relief.

After nine months of violence, the formal end was written with ink on paper—on a table that could have been used for any meeting—surrounded by a crowd that knew the paper represented thousands of lives.

Picture the visual contrast:

-

uniforms and insignia beside ordinary wooden chairs

-

a legal document beside the raw emotion of a crowd

-

formal posture beside trembling hands

-

a public ground that had hosted speeches and gatherings, now hosting a conclusion

This is part of what 16 December “looked like”—the meeting of the ordinary and the unimaginable.

The Signature: What Actually Happened at the Moment of Surrender

The core fact is simple and enormously consequential: Pakistan’s Eastern Command surrendered to the joint command led by India’s Eastern Command, with the surrender covering military forces in Bangladesh and committing to treatment of surrendered personnel under international norms.

This was not a rumor of surrender or an informal ceasefire. It was a formal, written instrument—signed by senior commanders—ending organized Pakistani military control in East Pakistan.

When we say “Dhaka changed forever,” this is the hinge.

Because once that signature existed, the city’s future was no longer a question. It was a direction.

What the Crowd Felt: Joy as Proof, Not Just Celebration

When people talk about Victory Day, they often describe the joy. But the joy of 16 December 1971 wasn’t just happiness—it was a form of proof.

Under occupation, joy can feel dangerous, like something that attracts punishment. On liberation day, joy becomes a civic act. It becomes public. It becomes loud. It becomes a way of telling your neighbors, “This is real. This is happening. Come outside.”

Crowds at the Racecourse weren’t only attending an event; they were confirming a reality together. In a society traumatized by months of fear, collective confirmation is powerful. It replaces isolation with shared truth.

And there was another layer: grief.

For many, joy and grief arrived together. Victory did not resurrect the dead. It did not undo what had been done. It did not return the missing. So the city’s celebration carried weight. People cried not only because they were happy but also because the months behind them had been too heavy to carry silently any longer.

The First Night of Freedom: Lights in the Windows

If the surrender ceremony was the official end, the night of 16 December was the emotional beginning.

Eyewitness memory describes neighborhoods staying bright—lights on, windows open, people refusing to hide. In places where street lighting was limited, homes themselves lit the streets. That image is more than a poetic detail; it is a psychological reversal.

Under occupation, many people learn to keep lights low, movements minimal, and attention avoided. On the first night of freedom, turning on lights becomes a statement:

-

“We are here.”

-

“We are not hiding.”

-

“This city belongs to its people again.”

Small processions moved through streets. People sang. They spoke loudly. They gathered. They reclaimed public space.

You can imagine Dhaka’s soundscape changing in real time: the return of spontaneous shouting, open laughter, songs carried down lanes, and doors opening again and again as neighbors stepped out to confirm that the world had truly turned.

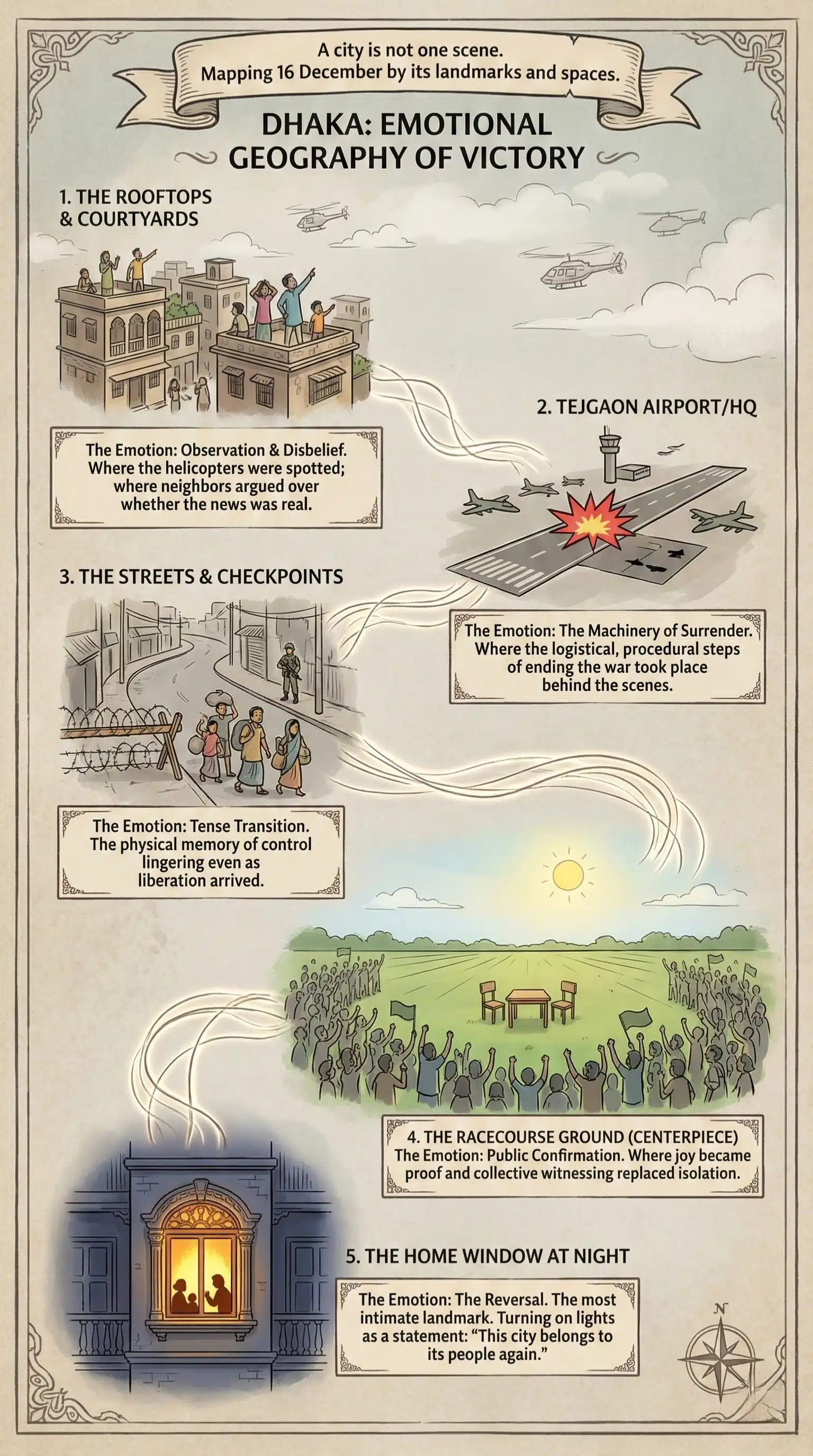

What Dhaka Looked Like, Place by Place

Because Dhaka is not one scene, it helps to map the day by the city’s landmarks and spaces.

Rooftops and Courtyards

The day’s early confirmation came from above. Rooftops became observation decks. Courtyards became gathering spaces. People pointed, argued, smiled, and corrected one another: “That’s an Indian helicopter.” “No, that’s—” “Shh, listen.”

Roads and Checkpoints

Even as the end arrived, the city still had the physical memory of control: checkpoints, guarded areas, and vehicles moving with urgency. Transitions are messy; old structures don’t vanish instantly.

Tejgaon

Airfields are where history arrives with paperwork. The movement of senior officials and documents through Tejgaon helped translate military reality into formal surrender.

Ramna Racecourse Ground (Suhrawardy Udyan)

The open ground where the public could witness the conclusion. A place where the city’s political identity was visible in a single frame: a crowd, commanders, and a document.

Homes at Night

The most intimate landmark: the window. Light behind curtains. Doors opened. Families gathered. Dhaka turned itself on again.

A Careful Note About Numbers and “Largest Surrender” Claims

Many popular accounts state that around 90,000+ Pakistani personnel became prisoners of war after the surrender and describe it as one of the largest mass surrenders since World War II. The figure is widely repeated in journalism and public history, but it can vary depending on what categories are included (regular troops, paramilitary forces, associated personnel, etc.).

For publication accuracy, it’s safest to present the figure as a widely cited estimate rather than an exact headcount—unless you’re quoting a specific official tally from a primary document.

The essential reality remains unchanged: the surrender involved a massive number of forces and effectively ended Pakistan’s military authority in Bangladesh.

Why Dhaka Changed Forever

Cities change with flyovers and new buildings. Dhaka changed on 16 December 1971 at a deeper level: it changed in the relationship between ordinary people and power.

Before victory, the city’s public space was controlled. Speech was dangerous. Movement could be punished. Information had to be hidden in whispers.

After victory, public space reopened. Speech returned. Light returned. The capital became a place where the flag and the streets and the air itself belonged to a new national story.

That is why people still say Dhaka changed forever. Because the day did not merely end a war; it rearranged what it meant to live openly in the city.

Final Words

Victory Day is often remembered through ceremonies, flags, and familiar phrases—and those matter. But if we want to honor 16 December with integrity, we have to remember it as Dhaka lived it: as a day of tense waiting and sudden release, of public history and private heartbreak, of paper and ink carrying the weight of lives.

Dhaka changed forever not because one document was signed—though that signature was decisive—but because a city that had been forced into silence found its voice again. People looked up, listened carefully, stepped out, and reclaimed the ordinary things that occupation had made extraordinary: open windows, bright homes, conversations without fear, and walking in the street without calculating consequences.

If you’re reading this in 2025, the most meaningful way to observe Victory Day may be to carry both truths at once: the joy of liberation and the cost of it. To resist turning history into a poster. To anchor remembrance in verified facts, while making space for the human reality behind them. Because the spirit of 16 December isn’t only about what happened—it’s about what it demanded from the living afterward: responsibility, dignity, and the courage to protect freedom once it has been won.