There are some artists who live for fame—and then there was SM Sultan, a man who walked away from it.

Nestled in the quiet heart of Bangladesh’s Narail district, his home by the Chitra River still feels alive with whispers of brushstrokes, laughter of children, and echoes of his dreams. Every year, thousands of art lovers, students, and curious travelers make their way to this humble corner of rural Bengal—not to see monuments of stone or gold, but to visit the living legacy of a man who painted strength, dignity, and humanity.

Today, Narail is more than a town; it’s a pilgrimage site for art and soul. And the story of how this transformation happened begins with one extraordinary man who believed that the soil itself could be a canvas.

The Roots of a Genius: Narail and Early Inspirations

Born on August 10, 1923, in the small village of Masimdia, Sheikh Mohammed Sultan grew up surrounded by fields, rivers, and farmers who toiled under the blazing sun. His father was a mason, and the young Sultan spent hours watching him craft shapes out of earth—perhaps the first lesson in form and structure.

He didn’t attend art school in the beginning; nature was his classroom, and the people of Bengal were his muses. As a child, he would sketch faces with charcoal, trace animals in the dust, and mix colors using soil and crushed leaves. There was something mystical about the way he observed life—a boy who saw art not as a luxury, but as an inseparable part of human labor.

This deep connection to the land and its people would later define his work. In every painting, Sultan celebrated rural Bengal’s unsung heroes—muscular farmers, resilient women, and an eternal bond between humans and nature.

From Narail to the World: The Artistic Odyssey

Despite coming from a small village, Sultan’s talent was too vast to stay hidden. In the 1940s, he moved to Calcutta, where he came under the influence of renowned artists and intellectuals of the time. Though briefly enrolled in the Government School of Art, he never conformed to its rigid norms. His art was instinctive—untamed, unfiltered, and emotionally raw.

Soon, his works began to attract attention beyond Bengal. His first major exhibition in Lahore (1952) stunned critics and viewers alike. They had never seen peasants painted like this—towering figures with divine strength, bathed in earthy tones, carrying the dignity of gods.

From Lahore and Karachi to New York, Sultan’s paintings crossed borders. But while his fame grew abroad, he remained detached. The glamour of galleries and patrons could not hold him for long. The city lights faded, and the riverbanks of Narail began calling him home.

The Return Home: Building an Artistic Utopia in Narail

When Sultan returned to Narail, he came not as a celebrated artist but as a philosopher of simplicity. Instead of chasing global recognition, he chose to live among the people who had inspired his art in the first place.

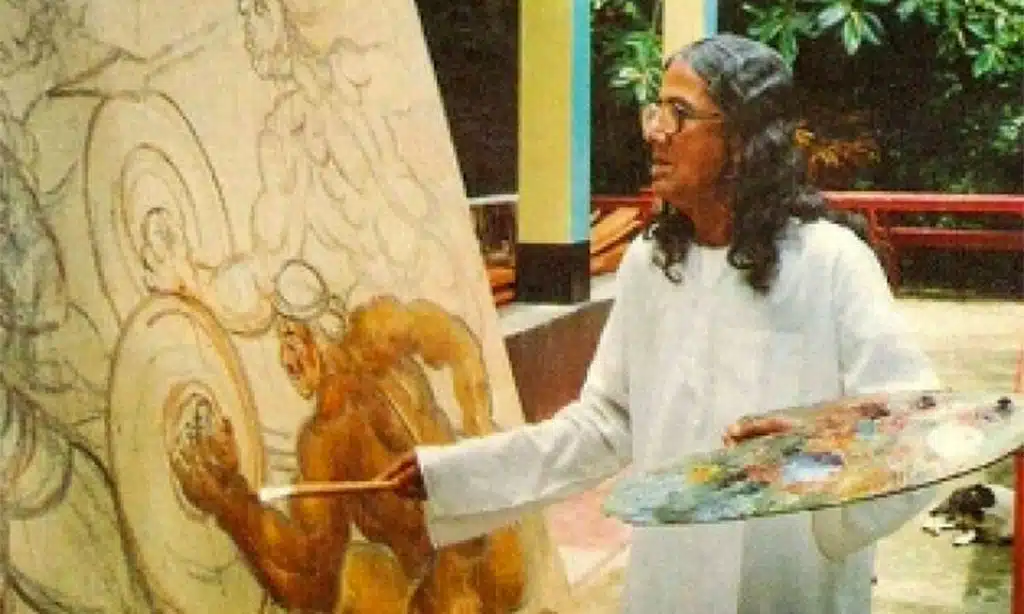

By the banks of the Chitra River, he built a small, open-air studio—a school without walls, as he called it. Children from nearby villages would gather every afternoon to draw, paint, and listen to his stories. He taught them that art wasn’t about technique or fame; it was about seeing beauty in one’s surroundings—in the sweat of a farmer, the rhythm of a plough, or the golden light over paddy fields.

Sultan would often say that the real artists were the villagers themselves, who painted life through their labor every day. His home became a sanctuary of creativity, filled with laughter, stray dogs, clay models, and unfinished sketches.

For Narail, this was more than art education—it was awakening.

The Birth of the Sultan Complex: Preserving a Legend

After his death in 1994, Bangladesh realized that Sultan had left behind more than paintings; he had left behind a philosophy. To honor his memory, the government and local authorities established the Sultan Complex in Narail—a beautiful tribute built near his home and resting place.

The complex includes a museum, library, art gallery, and a preserved version of his living quarters. Walking through it feels like stepping into his world—his brushes, his smoking pipes, the worn-out chair by the river window, and black-and-white photographs that capture his quiet genius.

The architecture mirrors his values—humble, organic, and connected to nature. There are no grand gates or marble halls, just open spaces filled with light and silence, where visitors can feel both awe and peace.

The Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy plays a key role in preserving his artworks and memories. Over the years, artists, researchers, and travelers from across the world have visited the Sultan Complex, turning Narail into a living museum of rural art and philosophy.

The Sultan Mela: A Living Celebration of Art and Humanity

Every year, when winter softens into spring, Narail awakens in color.

The quiet river town turns festive as the Sultan Mela begins — an event that brings together painters, musicians, poets, and villagers in one joyful celebration of creativity.

The fair isn’t just an exhibition; it’s a cultural heartbeat. Stalls display paintings and handicrafts; boats glide across the Chitra with lights; folk singers perform under the open sky. Children compete in art contests, their little hands smudged with color — a scene that Sultan himself would have loved.

For locals, the Mela isn’t about selling art; it’s about keeping a promise — to continue what Sultan started: art that belongs to everyone.

Visitors from Dhaka, Kolkata, and even abroad travel to Narail for these few days to experience what can only be described as a living tribute.

The festival has also brought economic and cultural benefits to the region. Local artisans find new audiences; hotels and homestays thrive; and the younger generation grows up seeing art as part of daily life, not a distant idea reserved for galleries.

It’s a unique ecosystem — a community built around the memory of a man who believed “beauty lives in the ordinary.”

The Legacy Beyond Paintings: Philosophy, Education, and Ecology

SM Sultan’s art wasn’t confined to canvas. It was a way of life — one deeply intertwined with ethics, ecology, and education.

He saw art as a force that could heal, inspire, and unify. In his view, every farmer was an artist shaping the earth, and every harvest was a masterpiece.

In an age when modernization was rapidly disconnecting people from nature, Sultan’s work stood as a gentle rebellion. His paintings of muscular peasants and fertile landscapes were more than aesthetic; they were political statements — celebrating human labor and critiquing industrial greed.

Environmentalists and modern eco-artists today find parallels between Sultan’s vision and the global “eco-aesthetic” movement. His harmonious portrayal of man, land, and beast anticipates ideas we now call sustainable living.

Beyond philosophy, Sultan also revolutionized the way rural Bangladesh thought about education. He wanted children to dream freely, without the boundaries of textbooks. His informal “art school” encouraged creativity and storytelling — long before the concept of “creative learning” became popular.

Those who studied under him still recall his simple but profound lessons: “Draw what you see, not what others tell you to see.”

Narail Today: From a Quiet Village to a Cultural Landmark

Thanks to Sultan’s influence, Narail is no longer an anonymous dot on Bangladesh’s map. It has transformed into a cultural hub that attracts artists, journalists, and tourists throughout the year.

The Sultan Complex remains the centerpiece, but the impact extends far beyond its walls. Local initiatives have sprung up — art workshops, rural galleries, and community exhibitions inspired by Sultan’s dream.

The Narail Express Foundation, for instance, works to promote creative education and preserve Sultan’s heritage while improving livelihoods in the area.

The local government has also improved infrastructure — better roads, guesthouses, and cultural centers — to make Narail more accessible. Yet, despite these modern touches, the town has retained its rural charm.

Walk along the Chitra River at sunset, and you’ll still see fishermen casting their nets, women washing clothes, and children sketching under banyan trees. It’s as if Sultan’s paintings have quietly stepped off the canvas and merged with real life.

But challenges remain. The preservation of Sultan’s original works, which are sensitive to humidity and time, demands ongoing care. Funding for art programs can be irregular, and many rural artists still struggle to gain national exposure.

Even so, the spirit of the place refuses to fade. Every brushstroke made in Narail, every melody sung at the Mela, carries the echo of his vision — art as life, life as art.

The Spirit of Sultan: Why Narail Still Breathes His Art

SM Sultan passed away on October 10, 1994, but for the people of Narail, he never truly left.

His presence lingers in the rippling river, in the laughter of children painting outside, and in the earthy scent of the soil he once immortalized.

Villagers still speak of him with affection — not as a celebrity, but as “Sultan Bhai,” the gentle man who walked barefoot through muddy paths, helping repair roofs, feeding stray animals, and teaching kids to draw sunsets.

For them, Sultan was more than an artist; he was a philosopher of humanity.

He rejected material success and chose a life of simplicity because he believed the purpose of art was to serve society, not to decorate it.

In an era dominated by technology and urban ambition, Sultan’s ideals feel almost radical — yet deeply needed. His life reminds us that art can be both personal and communal, both visionary and humble.

Even today, young artists from Narail carry forward his spirit. Their works — often depicting rural life, women in fields, or pastoral harmony — feel like continuations of his canvas.

Key Takeaways: The Making of an Art Pilgrimage

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Birthplace & Inspiration | Masimdia, Narail — rural life inspired his entire artistic vision. |

| Philosophy | Art belongs to everyone; beauty lies in labor and simplicity. |

| Landmark | The Sultan Complex preserves his legacy and home. |

| Cultural Celebration | The annual Sultan Mela unites art, music, and rural heritage. |

| Impact | Narail became a symbol of grassroots creativity and national pride. |

Final Words

SM Sultan dreamed of a world where art would not be confined to elite circles but would bloom in every household, school, and riverbank.

In Narail, that dream has taken shape.

This once-quiet village now stands as a beacon of creative consciousness — where children grow up surrounded by colors, festivals celebrate rural pride, and travelers leave with the feeling that they’ve touched something timeless.

Sultan didn’t just paint farmers; he painted a philosophy — one that blurred the line between art and life. His vision turned Narail into more than a birthplace — it became a sanctuary, a living museum of Bangladesh’s soul.

As you walk past the Chitra River at dusk, the light softens, and you can almost imagine him there — brush in hand, smiling quietly, watching the colors of his beloved land merge into the horizon.

In Narail, every leaf, every field, every face still whispers SM Sultan’s dream — a dream where art is not seen, but lived.