Using the James Webb Space Telescope and new X‑ray observatories, astronomers have identified the oldest known supernova and the fastest black hole winds on record, offering a rare glimpse of how the early universe and active galaxies evolve.

Two record-breaking cosmic blasts

Astronomers have announced two linked milestones: the detection of the oldest supernova ever seen and the fastest winds ever recorded from a supermassive black hole. The discoveries, made with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and powerful X‑ray missions, show how the oldest supernova and fastest black hole winds together illuminate the violent processes that shaped the young universe and continue to re‑engineer galaxies today.

Oldest supernova from the universe’s dawn

NASA reports that JWST has confirmed a supernova whose light left its host galaxy when the universe was just about 730 million years old, roughly 5% of its current age. The explosion is associated with a long gamma‑ray burst called GRB 250314A, making it the most distant and therefore oldest supernova ever confirmed, with the light traveling for around 13 billion years before reaching Earth.

The first sign of the event came on 14 March 2025, when the Franco‑Chinese SVOM satellite detected a bright gamma‑ray flash lasting about 10 seconds, a typical signature of a massive star collapsing to form a black hole. Within about 90 minutes, NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory pinpointed the X‑ray afterglow, allowing follow‑up by ground‑based telescopes. The Nordic Optical Telescope in the Canary Islands quickly spotted an infrared afterglow, hinting that the blast originated from an extremely distant, early galaxy.

A few hours later, the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile measured the object’s redshift, indicating that the explosion occurred when the universe was only about 730 million years old, during the so‑called Era of Reionization. Astronomers then scheduled JWST’s Near‑Infrared Camera (NIRCam) to observe the field on 1 July 2025, roughly three and a half months after the burst—when the underlying supernova was expected to be brightest due to cosmic time‑stretching.

JWST’s sharp infrared images revealed a faint, reddened point of light brightening where the burst occurred, along with an extremely small, dim host galaxy at redshift about 7.3. That single system now holds the record for the earliest known supernova and one of the earliest galaxies whose explosion has been directly resolved. NASA notes that this breaks JWST’s own previous record, which was a supernova that exploded when the universe was about 1.8 billion years old.

What the ancient blast tells us

Early theoretical models suggested that the first generations of stars were more massive, shorter‑lived, and chemically simpler than stars forming today, yet the new observations show that this ultra‑distant supernova looks surprisingly similar to modern core‑collapse supernovae. Astronomers comparing its light curve and spectral properties to nearby examples find that, despite forming in a much younger, less metal‑rich cosmos, the explosion behaves in familiar ways.

That similarity raises questions about how quickly heavy elements and “normal” stellar populations emerged after the Big Bang. By tying a specific supernova to a host galaxy so early in cosmic history, JWST is giving researchers a direct way to probe how massive stars lived and died during reionization, when radiation from the first galaxies was transforming the foggy early universe into a transparent one.

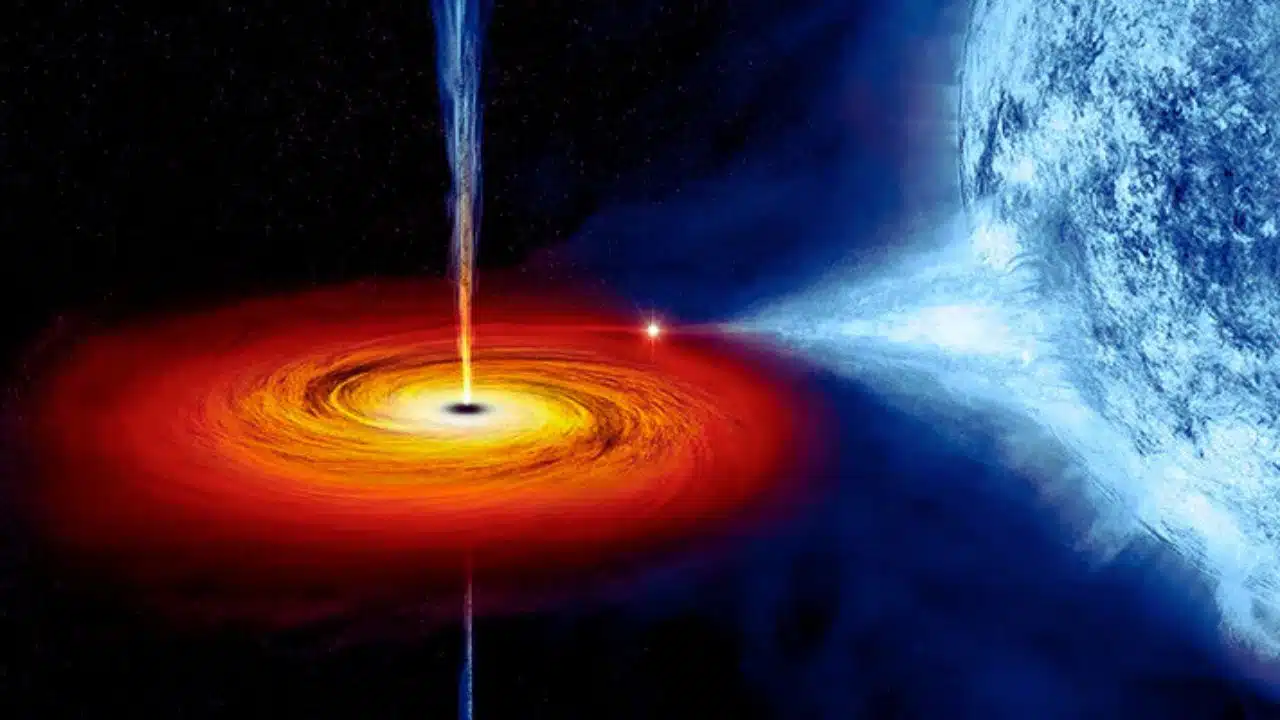

Fastest black hole winds ever observed

At nearly the same time, another international team has reported ultra‑fast winds blasting from a supermassive black hole at the center of the spiral galaxy NGC 3783, around 130 million light‑years from Earth. Using the new XRISM X‑ray telescope, led by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency with contributions from NASA and ESA, along with ESA’s XMM‑Newton observatory, the researchers watched a sudden X‑ray flare trigger a storm of matter racing outward at about 134 million miles per hour—roughly 60,000 kilometers per second, or 20% of the speed of light.

The active galactic nucleus in NGC 3783 hosts a black hole estimated at about 30 million times the mass of the Sun. XRISM first detected a brief but intense X‑ray outburst from close to the black hole, followed a few hours later by signs of extremely hot, ionized gas flowing outwards at relativistic speeds. XMM‑Newton’s instruments helped map how extended this wind was and how it evolved after the flare.

According to ESA scientists, the data suggest that the winds formed when tangled magnetic field lines near the black hole’s accretion disk rapidly “untwisted,” a process similar to how solar flares and coronal mass ejections erupt from the Sun—but vastly more energetic. While the Sun’s eruptions typically reach a few million miles per hour, the NGC 3783 winds are more than 40 times faster, making them the quickest black hole–driven outflows ever measured in such detail.

Why such fast winds matter

Ultra‑fast outflows like those seen in NGC 3783 are a key piece of “feedback,” the set of processes through which black holes and their host galaxies interact. By dumping enormous energy and momentum into surrounding gas, these winds can heat, sweep out, or compress material, either shutting down star formation or triggering new bursts of stars depending on how and where they strike.

Researchers note that if a black hole drives out too much gas too quickly, it may starve itself of fuel and stall the growth of both the black hole and the galaxy’s stellar population. On the other hand, episodic blasts can redistribute gas, stir turbulence, and help explain why galaxies stop forming stars at certain masses and times in cosmic history. The new observation, catching a flare and the onset of ultra‑fast winds within roughly a day, offers a rare time‑resolved view of how such feedback starts.

Key numbers at a glance

| Parameter | Oldest supernova (GRB 250314A) | Fastest black hole winds (NGC 3783) |

| Object type | Core‑collapse supernova linked to a long gamma‑ray burst | Ultra‑fast outflow from a supermassive black hole in an active galactic nucleus |

| Host galaxy epoch | About 730 million years after the Big Bang | Present‑day universe, galaxy ~130 million light‑years away |

| Approximate look‑back time | ~13 billion years | ~130 million years |

| Main observatories involved | SVOM, Neil Gehrels Swift, Nordic Optical Telescope, VLT, JWST | XRISM X‑ray telescope and ESA’s XMM‑Newton |

| Peak measured speed / energy sign | Gamma‑ray burst lasting ~10 seconds with long‑duration GRB energy output | Winds at ~134 million mph (~60,000 km/s), about 20% of light speed |

| Previous record it surpassed | Earlier JWST supernova at ~1.8 billion years after Big Bang | Earlier measured black hole winds significantly slower than 20% light speed |

| Discovery / publication date | Burst on 14 March 2025; JWST result published Dec. 2025 | Results published in Astronomy & Astrophysics in Dec. 2025 |

How the oldest supernova and fastest black hole winds reshape our view of the cosmos

Taken together, the oldest supernova and fastest black hole winds highlight how extreme events—stellar deaths and black hole outbursts—have driven change throughout cosmic history. The supernova tied to GRB 250314A shows that by 730 million years after the Big Bang, massive stars were already forming, collapsing, and enriching their galaxies much as they do today, even under very different early‑universe conditions.

Meanwhile, the NGC 3783 observations show that supermassive black holes can alter their host galaxies on short timescales, with winds ramping up from a flare to near‑relativistic speeds within hours. That kind of rapid, powerful feedback helps explain why astronomers see tight links between galaxy properties and the masses of the black holes in their centers. Together, the two results underscore how new observatories working in different wavelengths—infrared for JWST and X‑rays for XRISM and XMM‑Newton—are providing a more complete timeline of how the universe evolved from its first stars to the complex galaxies seen today.

What comes next for astronomers

Researchers already plan to use JWST’s rapid‑response programs to chase more gamma‑ray bursts in the early universe, hoping to build a larger sample of ancient supernovae and their host galaxies. By comparing many such events, they aim to test whether GRB 250314A is typical or unusual, and to refine models of how the first generations of massive stars lived, exploded, and seeded galaxies with heavy elements.

On the high‑energy side, teams working with XRISM and XMM‑Newton intend to keep monitoring active galactic nuclei like NGC 3783 to catch more flares and wind episodes in real time. Mapping how often such ultra‑fast winds occur, how long they last, and how much material they carry away will be vital for understanding how black holes regulate star formation and gas flows across cosmic time. With the oldest supernova and fastest black hole winds now on record, astronomers see these observations as just the beginning of a new era of time‑critical, multi‑wavelength astronomy.