For decades, the promise of limitless, carbon-free energy has been the definitive “holy grail” of physics, a tantalizing solution to our climate crisis that always seemed to be exactly thirty years away. However, as we stand in early 2026, the narrative has shifted from theoretical physics to industrial engineering.

Nuclear fusion breakthroughs are no longer confined to the pages of science fiction; they are becoming the cornerstone of a new global energy strategy. Driven by the voracious power demands of generative AI and a surge in private capital, the “fusion race” has entered its most decisive phase.

While the 1950s gave us the dream of “power too cheap to meter,” 2026 is giving us the first grid-scale pilot plants. This transition from laboratory experiments to commercial reality is being paved by high-temperature superconductors, artificial intelligence, and a fundamental rewriting of the limits of plasma physics.

Key Takeaways: The State of Fusion in 2026

- Regulatory Decoupling: Fusion is officially recognized as distinct (and safer) than fission.

- The AI Fuel: AI data centers are the “First Customers,” providing the urgent financial incentive for 2028-2030 grid connections.

- Material Science is the Bottleneck: The next 24 months will be defined by the “Scramble for REBCO” and Lithium-6 enrichment.

- Grid Parity is Coming: In some “high-capital” scenarios, fusion is projected to provide 10% of global electricity by the end of the century, with pilot plants proving the concept before 2030.

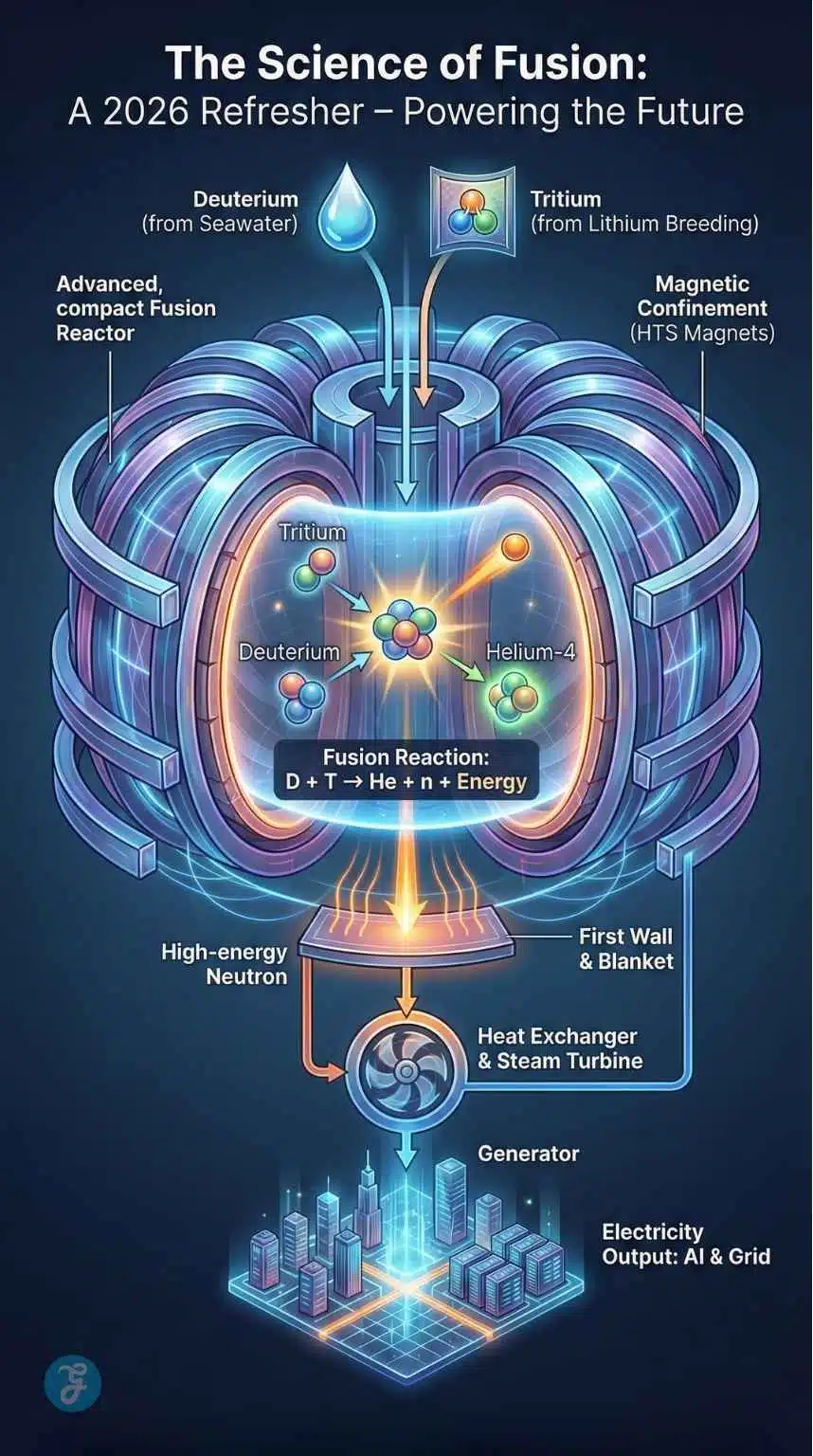

The Science of Fusion: A 2026 Refresher

To understand the magnitude of recent nuclear fusion breakthroughs, we must first look at the “Triple Product”—the combination of temperature, density, and time required to achieve a self-sustaining reaction. Unlike fission, which splits heavy atoms like Uranium, fusion involves squeezing light atoms (usually isotopes of hydrogen) together until they fuse into Helium, releasing a massive burst of energy in the process.

The Fuel Problem: Beyond the Laboratory

In 2026, the focus has shifted from making fusion happen to fueling it at scale. Most reactors today use a mix of Deuterium and Tritium (D-T fuel). While Deuterium can be extracted from seawater, Tritium is incredibly rare.

| Fuel Component | Source | Availability | Challenge |

| Deuterium | Seawater | Effectively Infinite | Extraction costs are minimal. |

| Tritium | Lithium Breeding | Scarce / Produced in-situ | Radioactive; requires complex “blanket” technology. |

| Helium-3 | Lunar Regolith / Synthetic | Extremely Rare | Requires advanced mining or non-standard reactions. |

The “Triple Product” Challenge

For fusion to provide more energy than it consumes (a state called “ignition”), the plasma must be:

- Hot enough: Over 100 million degrees Celsius (hotter than the sun’s core).

- Dense enough: Particles must be packed tightly to ensure they collide.

- Confined long enough: The magnetic or inertial fields must hold the plasma steady.

Landmark Breakthroughs: 2024–2026 Timeline

The last 24 months have seen a series of “firsts” that have shattered long-held skepticism. While the 2022 National Ignition Facility (NIF) breakthrough proved “net energy” was possible through lasers, the current era is dominated by magnetic confinement duration and density.

The Density Revolution [Late 2025]

In late 2025, researchers at China’s EAST reactor (Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak) achieved a breakthrough that many physicists thought impossible: they surpassed the Greenwald limit. Historically, if you tried to pack too much plasma into a tokamak, it would become unstable, and the reaction would collapse. By exceeding this limit by nearly 70%, the EAST team proved that we can build fusion reactors that are significantly more powerful without increasing their physical size.

The Long-Duration Pulse [Early 2026]

Duration has always been the Achilles’ heel of fusion. In early 2026, the WEST reactor in France maintained a stable, high-confinement plasma for over 20 minutes. This is a monumental jump from the few seconds of stability achieved only a few years prior. It signals that we are moving from “pulsed” fusion (short bursts) to “steady-state” fusion (continuous power).

| Milestone | Facility | Year | Why it Matters |

| Net Energy Gain | NIF (USA) | 2022 | Proved the physics of ignition. |

| 69MJ Energy Pulse | JET (UK) | 2024 | Record for magnetic energy production. |

| Greenwald Limit Break | EAST (China) | 2025 | Allows for smaller, denser, cheaper reactors. |

| 20-Minute Stability | WEST (France) | 2026 | Proves fusion can run as a “steady” power source. |

Strategic Alliances: The Rise of the “Fusion Bloc”

While the 20th century was defined by oil alliances like OPEC, 2026 is seeing the rise of “Fusion Blocs.” The international cooperation of the ITER era is being challenged by a new “Industrial Competition” model.

The 2026 Global Power Dynamics

The IAEA’s World Fusion Outlook 2025 highlighted a shift toward “Techno-Nationalism.” Countries are no longer just sharing data; they are competing to be the primary exporters of fusion hardware.

- The US-Japan Partnership: In late 2025, a joint venture between Kyoto Fusioneering and US-based startups established the first “Fusion Component Hub” in Tennessee, focused on remote maintenance robotics.

- Germany’s “FIRE” Roadmap: By the end of 2026, Germany plans to launch its “Fusion Energy Research and Innovation Roadmap,” aiming to bypass ITER’s delays with a domestic laser-fusion pilot.

- China’s Integrated Strategy: China remains the only nation with a “vertical” fusion strategy, controlling everything from the lithium mines to the reactor manufacturing plants.

The Tech Architectures: Tokamaks vs. The Field

The most visible nuclear fusion breakthroughs have come from Tokamaks—the donut-shaped machines that use magnets to trap plasma. But in 2026, the “best” design is still a subject of intense debate.

The Tokamak: The Traditional Heavyweight

Projects like ITER (the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor) represent the pinnacle of global cooperation. However, ITER is massive and slow. The focus in 2026 has shifted toward Compact Tokamaks. By using new magnet technology, companies like Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS) are building reactors that fit in a warehouse rather than a stadium.

The Stellarator: The Precision Machine

While Tokamaks are easier to build, they are prone to plasma disruptions. The Stellarator, exemplified by Germany’s Wendelstein 7-X, uses a twisted magnetic field that is inherently stable. In 2025, advanced 3D printing and AI-driven design allowed for the manufacturing of these complex magnets with sub-millimeter precision, making the Stellarator a viable commercial contender for the first time.

Alternative Approaches

- Magneto-Inertial Fusion: Companies like General Fusion use physical pistons to compress plasma.

- Field-Reversed Configuration (FRC): Used by Helion Energy, this approach aims to recover energy directly from the magnetic field, bypassing traditional steam turbines.

High-Temperature Superconductors (HTS): The Secret Sauce

If you ask a fusion engineer in 2026 what changed the most in the last five years, they won’t say “the physics”, they will say “the magnets.”

The advent of High-Temperature Superconductors (HTS), specifically those made from REBCO (Rare-Earth Barium Copper Oxide), has been the single greatest catalyst for recent nuclear fusion breakthroughs.

Why HTS Changes Everything

- Stronger Fields: HTS magnets can produce magnetic fields twice as strong as traditional low-temperature magnets.

- Compact Designs: Because the magnetic field is stronger, the reactor can be 10 to 40 times smaller in volume while producing the same amount of power.

- Higher Operating Temps: These magnets don’t need to be cooled to near absolute zero, reducing the energy “tax” required to run the reactor.

The SPARC Milestone [2026]

In 2026, the SPARC reactor at Commonwealth Fusion Systems is preparing for its first plasma. SPARC is the first machine designed specifically around HTS magnets. If it achieves net energy gain as predicted in 2027, it will effectively render the giant, multi-billion-dollar reactors of the past obsolete.

The Fusion Supply Chain: Beyond the Reactor

One of the most overlooked nuclear fusion breakthroughs of 2026 isn’t the plasma itself, but the birth of a specialized industrial supply chain. Building a star on Earth requires materials that didn’t exist in commercial quantities five years ago.

Critical Material Dependencies

The race for fusion is, in many ways, a race for rare materials. The “First Wall” problem, finding materials that can survive the neutron flux, has led to a surge in specialized manufacturing.

- REBCO Tape: Rare-Earth Barium Copper Oxide is the lifeblood of HTS magnets. In 2026, global production of this tape tripled, yet demand from companies like Tokamak Energy and CFS still outstrips supply.

- Lithium-6 Enrichment: To “breed” Tritium fuel, reactors need Lithium-6. Currently, enrichment facilities are a major bottleneck, leading to new “Isotope Security” policies in the G7.

- Beryllium and Tungsten: The “Armor” of the reactor. In 2025, new 3D-printing techniques for tungsten (which has a notoriously high melting point) were perfected, allowing for complex, water-cooled heat shields.

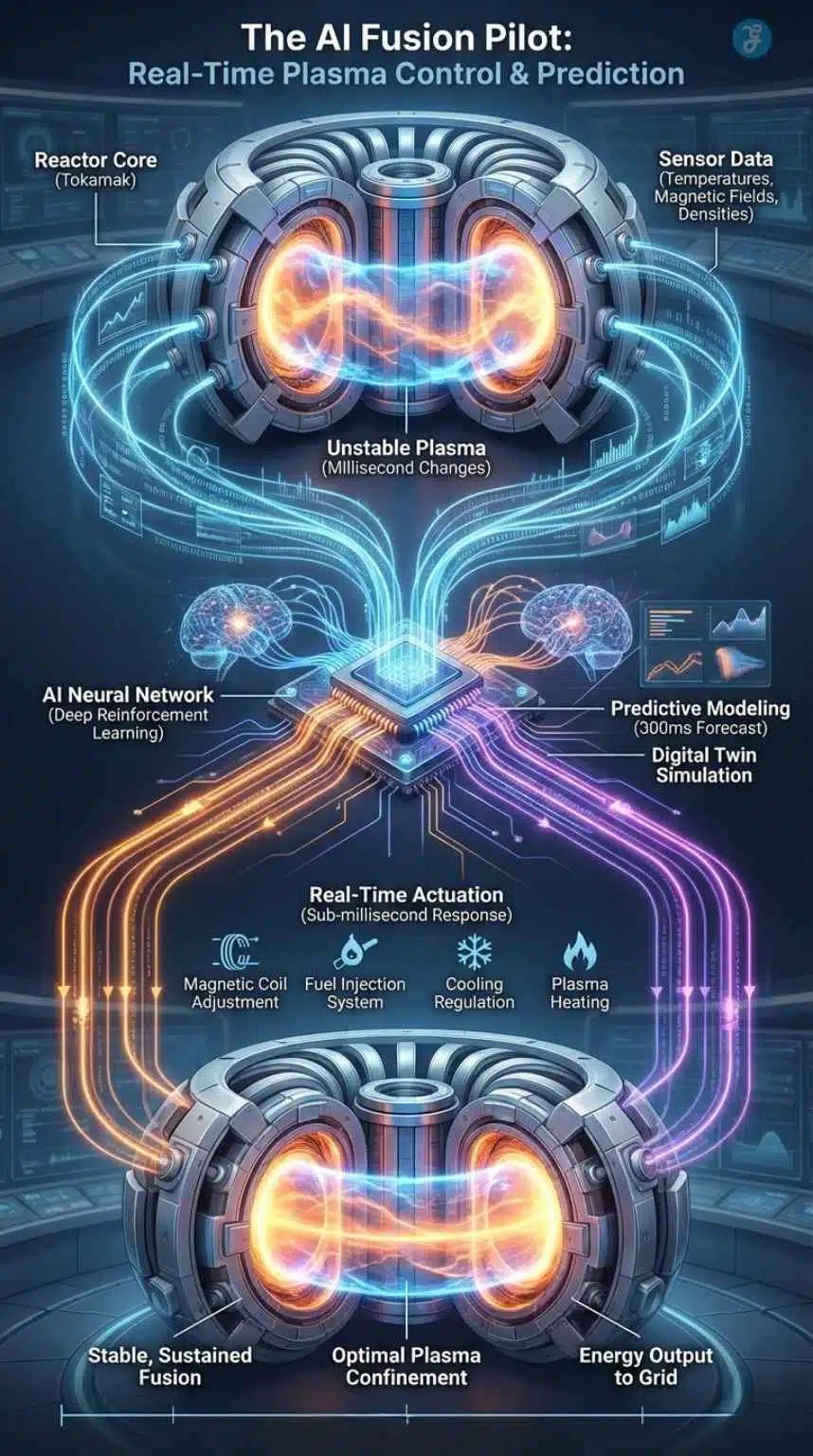

The AI Intersection: Real-Time Plasma Control

One of the most profound nuclear fusion breakthroughs of 2026 isn’t a piece of hardware; it’s an algorithm. Plasma is notoriously “flighty”; it wants to escape its magnetic cage every millisecond.

Deep Reinforcement Learning

Using neural networks trained on “Digital Twins” of reactors, AI systems can now predict plasma disruptions up to 300 milliseconds before they happen. This is long enough for the reactor’s magnetic coils to adjust and prevent a “quench” or collapse.

- NVIDIA and Siemens: Have partnered with fusion startups to create “Omniverse” simulations of reactor cores.

- AI-Optimized Design: AI is now being used to discover new alloys for the “First Wall” of reactors, the part that faces the extreme heat of the plasma.

Science Fiction vs. Reality: Addressing the Skepticism

Despite the hype, 2026 has also brought a dose of reality. We must separate what is scientifically possible from what is economically viable.

The “Q-Factor” Deception

When you hear a headline about “Net Energy Gain,” it usually refers to Q-plasma (the energy coming out of the plasma vs. the energy put into it). However, a commercial plant needs Q-engineering (the energy produced vs. the energy required to run the entire building).

| Metric | Scientific Reality (2026) | Commercial Goal (2030+) |

| Plasma Gain (Q) | Achieved (1.1 – 1.5) | Needs to be 10.0+ |

| Stability Duration | ~20 Minutes | Needs to be 24/7/365 |

| Capital Cost | ~$5-10 Billion (ITER) | Needs to be <$1 Billion |

| Energy Conversion | Steam Turbines (Mostly) | Direct Conversion (Target) |

The First Wall Problem

The “First Wall” of a reactor is hit by high-energy neutrons that make the materials radioactive and brittle over time. In 2026, research into liquid lithium walls has become a primary focus. These liquid walls “self-heal,” absorbing neutrons and heat without the structural degradation seen in solid tungsten.

The Private Sector: Big Tech’s Trillion-Dollar Bet

The demand for AI is driving a massive energy deficit. Microsoft, Google, and Amazon are no longer content waiting for government-funded fusion. They are now the primary financiers of nuclear fusion breakthroughs.

The Microsoft-Helion Agreement [2028 Update]

Microsoft’s 2023 agreement to buy fusion power from Helion Energy by 2028 was initially mocked. However, in 2025, Helion completed its “Polaris” machine, which successfully demonstrated the ability to recover magnetic energy directly. While 2028 remains an aggressive target for grid connection, the construction of their first commercial site in Washington state is currently ahead of schedule.

Venture Capital Shift

By the start of 2026, private investment in fusion surpassed $12 billion. This capital is being used to build smaller “fast-track” reactors that aim to iterate like software companies rather than traditional utilities.

The Regulatory Shift: Licensing the Stars

As nuclear fusion breakthroughs move from the lab to the landscape, the world’s regulatory bodies have had to perform a rapid pivot. Historically, fusion was lumped into the same legal category as fission (nuclear power). However, 2025 and 2026 have seen a “Great Decoupling” in policy.

The 2026 Regulatory Landscape

In early 2026, the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) finalized its “Byproduct Materials Framework.” This is a landmark decision because it regulates fusion reactors more like medical particle accelerators than traditional nuclear plants. This reduces the “regulatory tax”—the time and cost of licensing—by decades.

| Region | Regulatory Status (2026) | Key Focus |

| United States | ADVANCE Act (2024) Codified | Streamlined licensing for mass-manufactured units. |

| European Union | EU Fusion Strategy (Q4 2025) | Harmonizing safety standards across 27 member states. |

| Japan | Fusion Energy Innovation Strategy | Public-private “FAST” project site selection. |

| United Kingdom | Fusion Energy Bill | Maintaining a separate status from fission since 2023. |

This regulatory clarity is the “green light” that institutional investors were waiting for. Without the fear of 20-year licensing battles, fusion has become a “bankable” technology for the first time in history.

The Global Economic and Geopolitical Impact

A world powered by fusion looks fundamentally different from our current one. Because fusion uses isotopes found in seawater and lithium (common in batteries), it removes the geographical “lottery” of fossil fuels.

Energy Sovereignty

Nations that master fusion first will have a permanent strategic advantage. This has led to a “Fusion Cold War” between the US/EU and China. In 2026, we are seeing the emergence of Fusion Export Controls, where advanced magnet and HTS technology are treated as sensitive defense secrets.

Beyond the Power Grid

Fusion’s immense heat isn’t just for electricity. In 2025, the first white papers on Fusion-Powered Desalination and Green Hydrogen production were released. A single fusion plant could potentially provide fresh water for an entire coastal city as a “byproduct” of its electricity generation.

The Tritium Bottleneck of 2026

While we have mastered the physics of the reaction, we are facing a fuel crisis. Tritium has a half-life of only 12.3 years and is currently produced in aging fission reactors.

To solve this, 2026 has seen the rollout of Tritium Breeding Blankets. These are layers of lithium surrounding the reactor core. When neutrons from the fusion reaction hit the lithium, they “breed” more Tritium. For fusion to be sustainable, a reactor must produce at least 1.1 atoms of Tritium for every 1 atom it consumes.

| Breeding Method | Efficiency | Tech Readiness (2026) |

| Solid Lithium Pellets | Moderate | Tested in Labs |

| Liquid Lithium-Lead | High | Prototype Phase |

| External Synthesis | Low | Too Expensive |

Bridging the Gap to a Star-Powered Future

As we look toward 2030, the success of fusion will depend on our ability to build a global supply chain for superconductors and a regulatory framework that treats fusion as the safe, clean technology it is, rather than a cousin of traditional nuclear fission. The stars have always been our guide; now, we are finally bringing their fire down to Earth.

Final Thoughts: Crossing the Rubicon of Energy

The nuclear fusion breakthroughs of 2024–2026 represent a fundamental “Crossing of the Rubicon.” We have moved past the era of questioning the physics and into the era of solving the engineering. Fusion is no longer a distant dream; it is a strategic necessity for a world that requires exponentially more power for AI, carbon removal, and global development.

The transition will not be instantaneous. The first fusion electrons on the grid in 2028 or 2030 will be expensive and rare. The year 2026 will be remembered not as the year we “solved” fusion, but as the year we “industrialized” it.

We are no longer waiting for a single “Eureka!” moment; we are watching a thousand small engineering victories coalesce into a new pillar of human civilization.