The influence of Economic Sanctions is one of the most misunderstood forces in modern geopolitics. Many people see sanctions as a simple “punishment” tool, but in practice, they are closer to a pressure system that reshapes incentives across trade, finance, diplomacy, and even domestic politics. When sanctions land on a major state, the effects rarely stay contained. They ripple through supply chains, alliance commitments, currency access, military planning, and the credibility of international rules.

This article explains how sanctions change global power dynamics in real terms. It focuses on how leverage is created, how rival blocs harden, and how countries adapt when economic constraints become strategic constraints.

What Economic Sanctions Really Are in Power Politics

Economic sanctions are restrictions imposed by one state, or a group of states, to change another actor’s behavior. They often target trade, banking access, specific industries, and key individuals. But the deeper function is political: sanctions are a way to raise the cost of certain choices without firing a shot.

In power politics, sanctions operate like a bargaining signal. They communicate that a coalition is willing to absorb some economic pain to impose greater pain on a target. That signal matters because it shapes expectations. If the coalition looks united and durable, sanctions gain credibility. If unity fractures, sanctions weaken quickly, and the target learns it can wait the pressure out.

Sanctions can be broad or narrow. Broad sanctions can hit everyday economic life. Narrow sanctions can focus on sectors like defense, energy, technology, shipping, or finance. Regardless of type, the core question is the same: can the sanctioning side impose meaningful constraints while maintaining domestic support and coalition cohesion?

Types of Economic Sanctions and What They Actually Target

Economic sanctions are often discussed as if they’re one single tool, but in reality, they are a toolkit. Each sanction type targets a different “lever” of power—money, technology, logistics, legitimacy, or elite networks—and the choice of tool usually determines how fast pressure builds and how easy it is to evade.

1) Financial sanctions (the fast-acting pressure lever)

These include asset freezes, restrictions on dealing with specific banks, limits on sovereign debt issuance, and constraints on central bank reserves or key financial institutions. Financial sanctions matter because modern trade runs through credit, insurance, correspondent banking, and trusted payment channels. When those channels narrow, even “allowed” trade becomes expensive and slow.

2) Trade restrictions and embargoes (the visibility lever)

Import/export bans are politically clear and easy to communicate, but they can be blunt instruments. Broad trade sanctions can choke consumer goods, industrial inputs, and revenue streams—yet they also raise the risk of humanitarian harm and black markets.

3) Export controls (the long-game lever)

Export controls target advanced technology and dual-use items: high-end chips, precision machinery, aerospace components, encryption tools, specialized software, and industrial equipment. These sanctions often don’t create immediate collapse, but they can degrade long-term military modernization, high-tech production, and productivity growth.

4) Sectoral sanctions (the “capability” lever)

Sectoral sanctions restrict specific industries—energy, defense, mining, shipping, aviation, or telecom—without banning all trade. They’re designed to limit strategic capacity while leaving some economic space for negotiation.

5) Targeted or “smart” sanctions (the legitimacy lever)

These focus on individuals, oligarch networks, firms, and entities tied to state power. The theory is simple: squeeze decision-makers and their support systems rather than the public. In practice, targeted sanctions still spill over—especially when elite networks control major parts of the economy.

Choosing among these tools is strategic. It signals whether the goal is immediate deterrence, long-term weakening, elite fragmentation, negotiated compromise, or some combination of all four.

How Sanctions Shift Leverage Without Changing Borders

Sanctions rarely change borders overnight. Their influence is usually slower and more structural. They shift leverage by limiting options, raising transaction costs, and forcing strategic trade-offs.

One major mechanism is financial access. When a country’s banks, firms, or sovereign entities lose access to key currencies, settlement systems, or global credit, the entire economy becomes less flexible. Import costs rise. Investment slows. Technology access tightens. These changes reduce a state’s capacity to project power abroad, even if its military strength stays intact.

Another mechanism is technology bottlenecks. Modern power depends on complex technology ecosystems. Restricting high-end chips, precision equipment, aerospace components, or advanced software can weaken long-term competitiveness. Over time, that impacts military modernization, industrial resilience, and economic growth.

A third mechanism is reputational and diplomatic cost. Sanctions can stigmatize a target, making companies and states cautious even beyond formal legal limits. This “shadow effect” can isolate the target further, amplifying pressure without additional policy steps.

How Sanctions Are Enforced in Practice: Banks, Compliance, and Secondary Pressure

Sanctions only change power dynamics when they are enforced reliably. The most important battleground is not a border crossing—it’s the compliance architecture inside banks, shipping firms, insurers, manufacturers, cloud providers, and commodity traders.

Compliance is where pressure becomes real.

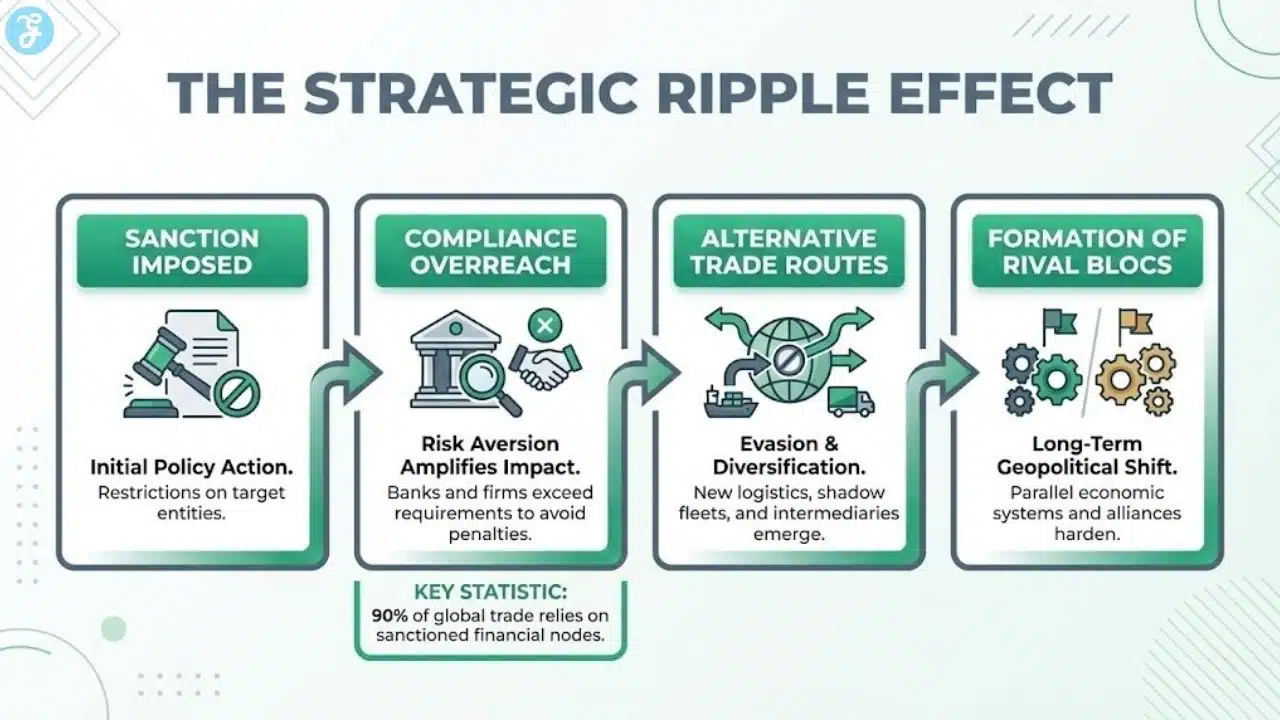

Once a sanctions package is announced, companies and banks must decide what risks they are willing to carry. Even if a transaction is technically legal, many institutions avoid anything that looks close to a restricted entity because penalties can be severe and reputational damage can be permanent. This creates a “compliance overreach” effect that often amplifies sanctions beyond what is written on paper.

The choke points are often private-sector nodes.

Sanctions gain strength when a coalition influences the infrastructure that global commerce depends on—letters of credit, shipping insurance, reinsurance markets, classification societies, port services, legal arbitration, and high-trust payment corridors. Cutting access to even one of these layers can raise the cost of trade dramatically.

Secondary sanctions expand power beyond the coalition.

Secondary sanctions threaten penalties on third-party firms or banks that do business with the target. This is one of the most powerful—and controversial—forms of economic leverage because it pushes “neutral” actors to choose between access to the sanctioning coalition’s markets and access to the target’s markets. In effect, the coalition exports its policy preferences outward through financial and commercial gravity.

Evasion becomes a cat-and-mouse game.

Targets frequently use front companies, re-export hubs, flag changes for ships, complex ownership structures, and indirect payments to keep trade flowing. That forces sanctioning states to invest in monitoring, intelligence sharing, and enforcement updates—because stale sanctions become porous sanctions.

The outcome is a network contest: the sanctioning side tries to tighten the system faster than the target can route around it. That network contest is a major reason sanctions reshape global power—even when they don’t produce immediate policy change.

Why Sanctions Often Strengthen Alliances

A strong sanctions regime is rarely the product of one country acting alone. It usually requires sanction coordination. That coordination can strengthen alliances because it forces members to align on goals, messaging, and enforcement.

Sanctions can become an alliance discipline tool. When partners enforce the same restrictions, they build shared intelligence channels, harmonize legal frameworks, and develop joint monitoring systems. Over time, these operational ties increase alliance capacity beyond the sanctions issue itself.

Sanctions can also clarify commitment. When states accept economic costs to support a shared stance, they demonstrate willingness to bear burdens. That can reassure allies and deter adversaries. It shows that a coalition can act collectively, not just speak collectively.

At the same time, sanctions can strain alliances if the burden is uneven. Energy-heavy economies, export-driven states, or countries with strong trade links to the target may feel higher pain. If domestic politics in those states turn against sanctions, unity becomes fragile.

The Influence of Economic Sanctions on Alliance Behavior

Sanctions shape alliances by turning values and security commitments into economic decisions. In many coalitions, the hardest question is not whether a target’s behavior is unacceptable. The hardest question is how much cost each member is willing to accept, and for how long.

Alliance behavior shifts in a few predictable ways:

-

Members push for exemptions that protect critical industries

-

Enforcement becomes a test of trust between partners

-

Secondary sanctions threats can create resentment inside coalitions

-

Some states position themselves as “bridges” to maintain leverage with both sides

This is where sanctions become a power contest inside the coalition, not just against the target. A member that controls critical infrastructure, shipping routes, financial hubs, or energy supplies may gain negotiating power within the alliance. That internal bargaining can reshape who leads and who follows.

Sanctions can also produce new mini-blocs inside alliances. Some members may favor maximum pressure. Others may favor limited pressure combined with negotiation incentives. Those differences can influence broader alliance strategy well beyond the sanctions issue.

How Targets Adapt and Why That Changes the Global Order

Sanctioned states rarely stay passive. They adapt. That adaptation can permanently alter global systems, especially when the target is large, resource-rich, or strategically connected.

Adaptation often takes several forms:

-

Building alternative trade routes and payment channels

-

Redirecting exports to non-participating states

-

Expanding domestic production to replace imports

-

Increasing barter or local-currency settlement

-

Deepening ties with rival powers that benefit from discounted access

These adaptations can weaken the sanctioning coalition’s leverage over time. Even if sanctions remain painful, the target may become more resilient. That resilience changes future bargaining dynamics because the target can claim it has “survived” and therefore can resist again.

Adaptation also affects third countries. States that do not want to be vulnerable to future sanctions may diversify reserves, develop alternative settlement systems, or reduce dependence on specific suppliers. This is one reason sanctions can accelerate long-term shifts in global economic architecture.

How Sanctions Reshape Energy and Commodity Power

Energy and commodities are often at the heart of sanctions battles. When a sanctioned state is a major exporter of oil, gas, fertilizers, metals, or grain, restrictions can raise global prices and pressure consumers far away from the conflict.

This creates a power dynamic where the target can still hold leverage. Even under sanctions, commodity exporters may use price shocks, supply redirection, or contract renegotiation to influence international behavior. Meanwhile, sanctioning states must manage domestic inflation risks and political backlash.

Sanctions also push importers to diversify suppliers. That can create new winners. Alternative exporters gain market share. Transit countries gain strategic value. Energy infrastructure projects become geopolitical tools because pipelines, LNG terminals, and shipping routes shape who depends on whom.

Over time, this can redraw influence maps. A state that becomes a key alternative supplier may gain diplomatic leverage. A state that controls a critical chokepoint may gain security importance. Sanctions can therefore shift power not only between sanctioner and target, but across entire regions.

When Sanctions Backfire and Why Power Still Changes

Sanctions can backfire in several ways. The most common is domestic backlash inside the sanctioning coalition. If citizens experience rising prices, job losses, or supply disruptions, political leaders may face pressure to soften enforcement. That weakens credibility and emboldens targets.

Sanctions can also backfire by strengthening the target’s internal narrative. Leaders may frame sanctions as external aggression, rallying domestic support and justifying tighter control. In those cases, sanctions may reduce the chance of policy change while increasing authoritarian sanction consolidation.

Another risk is unintended harm to third countries. If sanctions disrupt key supplies, poorer states may face severe shortages. That can create resentment toward sanctioning coalitions and open the door for rival powers to gain influence by offering alternative trade or aid.

Even when sanctions do not “work” in the narrow sense, they often still change power. They force new alignments, accelerate diversification, and reveal where global dependencies truly sit.

How Sanctions Create Rival Blocs and Competing Systems

One of the clearest long-term effects is bloc formation. When sanctions become frequent or severe, states begin to plan for a world where economic interdependence is not neutral. It becomes weaponized.

This can lead to:

-

Competing payment and settlement systems

-

Separate technology ecosystems and standards

-

Parallel supply chains designed for political reliability

-

New security partnerships built around economic survival

This is a major reason sanctions influence power dynamics even when they do not achieve immediate behavioral change. They encourage countries to treat economic architecture as a security asset, not just a market outcome.

Influence of Economic Sanctions becomes especially visible here because power is no longer measured only in military capability. It is measured in network access: who can trade, who can borrow, who can insure shipments, who can source components, and who can move money reliably.

How Sanctions Affect Smaller States and Middle Powers

Sanctions are not only about great powers. Smaller states and middle powers often face the toughest choices because they live inside competing economic and security networks.

A middle power may rely on one bloc for security support and another bloc for trade. When sanctions intensify, neutrality becomes expensive. Choosing one side may mean losing markets. Choosing the other may mean losing security cooperation.

Many smaller states respond by trying to “hedge”:

-

Maintaining formal compliance while keeping informal trade channels

-

Seeking exemptions based on humanitarian or development needs

-

Increasing domestic production in critical sectors

-

Expanding regional trade agreements to reduce reliance on any one power

These strategies can reduce vulnerability, but they also reshape alliances and regional leadership. Over time, sanctions pressure can push smaller states into tighter regional groupings or new security arrangements.

Sanctions Power Shift Tracker

Use this section to make the “power dynamics” impacts measurable, not abstract.

-

Watch the chokepoints, not the headlines: payment rails, shipping insurance, reinsurance, spare parts, and high-trust banks often matter more than formal trade bans.

-

Track coalition durability: sanctions gain power when enforcement stays consistent across months, not days.

-

Measure adaptation speed: the target’s ability to reroute trade, localize production, or shift currencies determines whether pressure compounds or fades.

-

Look for second-order effects: neutral states, commodity buyers, and regional hubs often become the real winners or losers.

Quick Metrics That Reveal Who Gains Leverage

| Signal To Track | What It Usually Indicates | Why It Matters For Power |

|---|---|---|

| Currency premium and capital controls | Financial strain and reduced flexibility | Limits procurement and foreign influence |

| Shipping rates and insurance availability | Logistics friction and hidden isolation | Raises trade costs even when trade is “allowed” |

| Tech substitution progress | Long-term resilience or stagnation | Shapes military modernization and productivity |

| Discounted commodity rerouting | New dependency chains | Creates leverage for new buyers and transit states |

Practical takeaway: the side that controls more “network access” nodes usually shapes the bargaining table, even without changing borders.

What This Means for the Future of Global Power

Sanctions are likely to remain a core tool because they offer a middle path between diplomacy and war. But they will be used in a world that is increasingly prepared to resist them. That means sanctions may become less decisive alone and more effective when combined with broader strategies.

Future power dynamics will likely depend on several factors:

-

Coalition durability and enforcement capacity

-

Control over financial and technological chokepoints

-

Resource security and supply chain resilience

-

The ability of targets to adapt and build alternatives

-

Domestic political tolerance for long-term economic pressure

In a fragmented system, economic pressure becomes less about one knockout blow and more about sustained influence over networks. States that control key nodes, finance, data infrastructure, shipping insurance, and high-end technology will maintain leverage. States that diversify dependencies and build redundancy will reduce vulnerability.