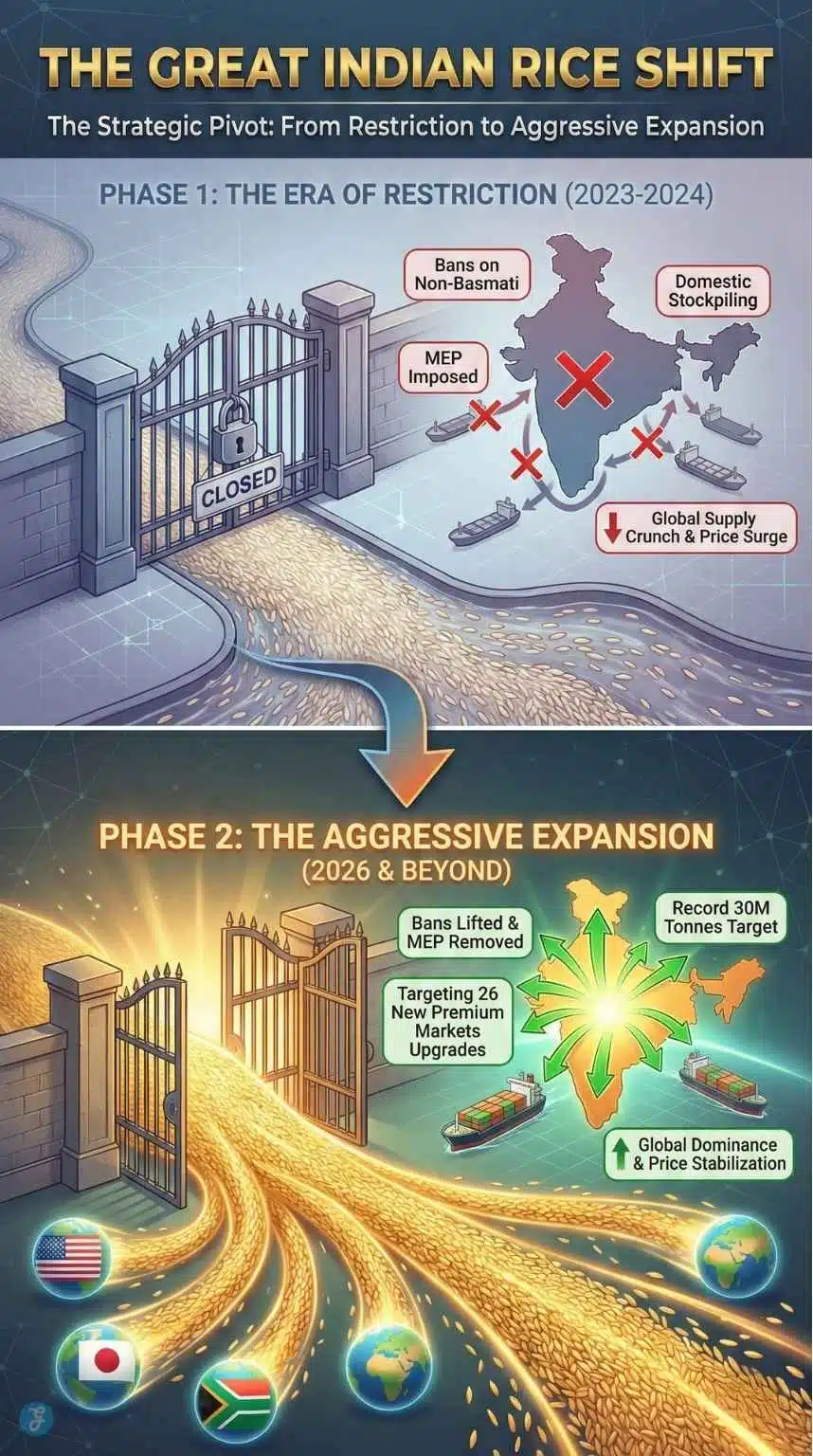

Two years ago, the global rice market was defined by scarcity and fear. In 2023, India Rice Exports, the world’s largest grain exporter, slammed the brakes on trade, imposing sweeping bans on non-basmati white rice to curb domestic inflation. The result was a global panic that sent prices soaring to 15-year highs. Fast forward to January 2026, and the pendulum has not just swung back; it has shattered the mechanism.

India has returned to the global stage with a vengeance. No longer content with merely “normalizing” trade, New Delhi has executed a calculated strategic pivot. With the complete removal of the Minimum Export Price (MEP) and the lifting of all non-basmati bans, India is flooding the market with record volumes. The country is now projecting an unprecedented 30 million tonnes of rice exports for the 2025–26 fiscal year, a figure that dwarfs the combined exports of its next three competitors.

This analysis examines how India’s aggressive re-entry is stabilizing domestic economics while simultaneously upending the trade balance of South Asia, forcing competitors into a price war they cannot afford to win.

Key Takeaways

-

Export Surge: India has lifted all bans and targets a record 30 million tonnes of rice exports for 2026.

-

Price Crash: The influx of supply has driven global prices down by 35%, with Indian rice trading significantly cheaper than competitors.

-

Winners & Losers: Importers like Bangladesh and Sri Lanka benefit from lower costs, while competitors like Pakistan and Thailand are losing market share.

-

Ethanol Buffer: To stabilize domestic prices, 5.2 million tonnes of surplus rice are being diverted to ethanol production.

-

Strategic Shift: The focus is moving to 26 new premium markets (like the US and Japan) to increase value, not just volume.

-

Future Risks: Sustainability concerns (groundwater depletion) and potential EU tariffs remain the biggest threats to long-term growth.

The Strategic Pivot: From Restriction to Aggressive Expansion

The “Rice Flood” of 2026 is not an accident of nature; it is a result of deliberate policy calibration. Following a record-breaking harvest of 150.18 million tonnes, officially surpassing China to make India the world’s largest rice producer, the government faced a new problem: overflowing granaries.

To manage this surplus, the strategy shifted from restriction to diversification.

1. Dismantling Barriers

By late 2025, the restrictive architecture of the previous years was dismantled.

-

MEP Removal: The floor price for basmati and non-basmati rice was scrapped, allowing Indian exporters to price their grain competitively against Thai and Vietnamese varieties.

-

Duty Rationalization: Export duties on parboiled rice were slashed to zero, instantly making Indian parboiled rice the cheapest option for African buyers.

2. Targeting New Frontiers

Historically, Indian non-basmati rice flowed to West Africa and Bangladesh. The 2026 strategy, however, targets value over just volume. The Ministry of Commerce has identified 26 new markets, moving beyond traditional buyers to premium destinations.

-

The “Culinary Diplomacy” Push: India is aggressively marketing GI-tagged (Geographical Indication) varieties like Joha (Assam) and Ambemohar (Maharashtra) to niche markets in Japan, the United States, and Mexico. These varieties are being positioned as “wellness grains” to compete with Jasmine rice.

-

Infrastructure Upgrades: To support this volume, new rail-connected rice hubs and Inland Container Depots (ICDs) in Punjab and Andhra Pradesh have been operationalized, reducing the “grain-drain” logistics costs that previously hampered efficiency.

The Domestic Balancing Act: Food vs. Fuel

While the world focuses on India’s export figures, a quieter but equally massive shift is happening domestically: the diversion of food grain to fuel. In a bid to hit its ambitious E20 (20% Ethanol Blending) target, the Indian government has authorized the Food Corporation of India (FCI) to allocate a record 5.2 million tonnes of rice for ethanol production in the 2025–26 cycle.

This creates a unique “floor” for the rice market. Unlike in previous years, where surplus stocks simply rotted in open storage, they are now being channeled into distilleries.

-

The Strategic Buffer: This dual-use policy acts as a price stabilizer. If export demand softens, the government can simply divert more grain to ethanol, preventing a total price collapse for farmers.

-

The Criticism: Critics argue that burning premium carbohydrates for fuel in a country with nutritional challenges is ethically complex, but from a purely trade perspective, it ensures that India’s exportable surplus is “manageable” rather than “desperate,” giving exporters better leverage in price negotiations.

Impact on South Asian Neighbors: Winners and Losers

India’s sheer volume acts as a gravitational force in South Asia. When India exports, the region reacts. The 2026 surge has created a stark divide between importing neighbors and exporting competitors.

Trade Impact Matrix: South Asia 2026

| Country | Status | Impact Analysis |

| Bangladesh | Winner | Inflation Relief: As a net importer, Bangladesh has benefited immensely. The influx of affordable Indian white rice has helped Dhaka cool its domestic food inflation, which had been a pain point in 2024–25. |

| Pakistan | Loser | Market Share Erosion: Pakistan’s rice sector, which enjoyed a “golden run” during India’s ban (growing exports by ~60%), is now in crisis. With Indian rice returning at $40-$50 cheaper per tonne, Pakistani exporters are seeing order cancellations from traditional buyers in East Africa. |

| Nepal | Mixed | Consumer vs. Farmer: While consumers enjoy lower prices, Nepali farmers are protesting the “dumping” of cheap Indian grain, which undermines their local harvest profitability. |

| Sri Lanka | Winner | Security: The resumption of stable supplies has allowed Sri Lanka to secure its food security buffer without draining its foreign exchange reserves on expensive alternatives. |

The Diplomatic Angle

New Delhi is leveraging this dominance for soft power. Through Government-to-Government (G2G) deals, India has locked in long-term supply quotas with Nepal and Sri Lanka. This “Rice Diplomacy” ensures that while the open market fluctuates, India remains the guarantor of food security for its neighbors, strengthening its geopolitical foothold in the region.

Global Market Ripples: The Price Crash

The global market operates on a simple rule: India sets the price.

With 40% of the global rice trade now back in Indian hands, the price discovery mechanism has shifted from Bangkok to New Delhi. The surge in Indian supply has forced a dramatic correction in global indices.

-

The Price War: Benchmark Thai 5% Broken rice, which traded near $650/tonne during the peak of the ban, has crashed to the $400–$440 range. Vietnam, struggling with higher production costs, has been forced to lower its prices to compete, squeezing farmer margins in the Mekong Delta.

-

The “Wait-and-Watch” Game: Major importers in the Philippines and Indonesia have adopted a “hand-to-mouth” buying strategy. Expecting Indian prices to bottom out further, they are delaying bulk purchases, which creates further inventory pressure on exporters globally.

Key Statistic: Pakistan’s rice exports plummeted by nearly 46% in the first quarter of the 2025–26 fiscal year immediately following India’s policy reversal.

The Headwinds: Regulatory Walls and Logistical Shadows

Despite the aggressive export push, Indian rice faces two significant external barriers in 2026 that could dampen the “30 million tonne” dream.

1. The “Fortress Europe” Mechanism

While India targets premium markets, the European Union is raising the drawbridge. In December 2025, the EU Council agreed on a new “Automatic Safeguard Mechanism” for rice imports, set to fully activate in 2027 but already influencing 2026 contracts.

-

The Trigger: If import volumes from a single country (read: India) surge significantly above historical averages, automatic tariffs will kick in to protect Italian and Spanish growers.

-

The Chemical Barrier: Beyond tariffs, the “MRL War” continues. The EU’s stringent Maximum Residue Limit (MRL) for Tricyclazole (a common fungicide used by Indian farmers) remains at a near-zero 0.01 ppm. This effectively blocks non-organic Indian rice from entering the EU, forcing exporters to route shipments through expensive “cleaning” hubs in the Middle East or face rejection.

2. The Logistics Shadow (Red Sea Crisis)

The geopolitical instability in the Red Sea remains a persistent “logistics tax” in 2026.

-

Cost Absorption: To remain competitive against Thailand (which has easier access to Pacific routes), Indian exporters are currently absorbing a significant portion of the inflated freight costs for shipments to Europe and the US East Coast.

-

The US Tariff Shadow: In the American market, buyers are demanding discounts of 7–8% to offset high import tariffs (roughly 50% on certain Indian goods). This squeezes the margins of Indian exporters, turning the US trade into a “high volume, low margin” game despite its premium status.

2026 Global Rice Price Comparison (FOB per Tonne)

| Variety | India (Offer Price) | Thailand (Competitor) | Vietnam (Competitor) | The “India Gap” |

| 5% Broken White Rice | $430 – $440 | $480 – $495 | $465 – $475 | India is ~$40 cheaper |

| Parboiled Rice | $395 – $405 | $450 – $460 | N/A (Low Vol) | India is ~$55 cheaper |

| Basmati / Fragrant | $950 – $1,050 | $920 – $980 (Hom Mali) | $880 – $950 (Jasmine) | Premium Parity |

Analyst Note: The “India Gap” is the primary driver of the current market shift. African buyers, who are price-sensitive, are almost exclusively switching back to Indian Parboiled rice due to the $55/tonne savings.

The Hidden Cost & Future Outlook

While the export figures are celebratory, the long-term cost of this dominance is becoming a central theme of the 2026 narrative.

1. The Water Crisis (The Environmental Cost)

Exporting 30 million tonnes of rice is effectively exporting billions of liters of water. Groundwater tables in Punjab and Haryana are depleting at alarming rates. The “Green Rice” initiative—part of the 2026 strategy—attempts to mitigate this by promoting Direct Seeded Rice (DSR) and shorter-duration varieties, but adoption remains slow compared to the export velocity.

2. Budget 2026 Demands

With the Union Budget due in February 2026, the Indian Rice Exporters Federation (IREF) is lobbying hard to sustain this momentum. Their key demands include:

-

Interest Subvention: A request for a 4% interest subsidy to lower the cost of credit for exporters.

-

Freight Support: Subsidies on rail freight to keep Indian rice competitive even as global shipping rates fluctuate.

If these demands are met in the upcoming budget, India could theoretically push its export ceiling even higher, cementing a monopoly-like status for the remainder of the decade.

The Bottom Line: A New Era of Rice Diplomacy

India’s return to the rice market in 2026 is not a restoration of the status quo; it is a redefinition of it. By leveraging record production and dismantling trade barriers, India Rice Exports has successfully stabilized domestic stocks while dealing a heavy blow to regional competitors like Pakistan and Thailand.

However, this dominance comes with a caveat. The strategy is currently volume-heavy and resource-intensive. For India to maintain this “throne” without draining its aquifers or triggering protectionist tariffs from other nations, the shift must eventually move from feeding the world to feeding the premium market.