George Washington is remembered as the face of American independence, but he also spent most of his life enslaving other human beings. That tension, liberty on paper, bondage in practice, sits at the heart of the “true story” of Washington and slavery. It’s not a simple tale of hero or villain. It’s the story of a powerful man shaped by a slave society, who benefited from it, protected it in office, and only near the end of his life took steps that moved, partly and imperfectly, toward emancipation.

As we mark the anniversary of his death on this day, December 14th, we look back not just on the end of his life, but on the final, complex decision that defined his legacy. To truly know Washington is to grapple with the uncomfortable reality of his dual existence as a champion of freedom and a master of Mount Vernon’s enslaved population.

The “true story” of Washington and slavery is not a simple narrative of a benevolent father figure, nor is it a one-dimensional villain story. That’s why understanding this history matters because Washington wasn’t a private citizen on the margins of the new nation. He was its most visible leader. What he did, what he refused to do, and what enslaved people did in response reveal how deeply slavery was woven into the founding era.

Key Takeaways

-

George Washington enslaved people throughout most of his life at Mount Vernon.

-

Slavery under Washington was large-scale and systematic, involving hundreds of enslaved individuals.

-

He expressed private doubts about slavery but defended it publicly as president.

-

Washington signed laws that strengthened slavery, including the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793.

-

Enslaved people resisted and escaped, asserting their right to freedom.

-

His emancipation efforts were real but limited, freeing only those he legally owned.

George Washington’s Early Life: Slavery as Inheritance and Assumption

Washington did not invent slavery in America, and he did not “discover” it as an adult. He was born into it. In colonial Virginia, slavery was a core economic system and a social norm for many white landowning families. Washington inherited enslaved people when he was young, and as he rose into the planter elite, enslaved labor became part of how he built wealth and status.

In practical terms, Washington’s early relationship to slavery looked like what many successful Virginia planters pursued: land expansion, higher production, and labor control. As his ambitions grew, so did his dependence on enslaved people to make his estate profitable.

A Plantation Complex Powered By Enslaved Labor

Mount Vernon was not a small farm with a handful of workers. It became a large plantation enterprise that Washington managed closely. He was known for detailed records and hands-on oversight. That efficiency—often praised in biographies—also meant he systematically organized enslaved people’s work to serve the estate’s productivity.

Enslaved people did the labor that kept Mount Vernon running: planting, harvesting, caring for livestock, building and repairing structures, crafting tools, cooking, laundering, and serving inside the mansion. Slavery at Mount Vernon was not abstract. It was daily, physical, and enforced.

The Business of Slavery: Life at Mount Vernon

Popular history often softens the image of slavery at Mount Vernon, painting a picture of a genteel estate where the enslaved were treated like extended family. The reality, however, was a harsh, industrial enterprise driven by Washington’s obsession with economic efficiency.

The Numbers: Who Owned Whom?

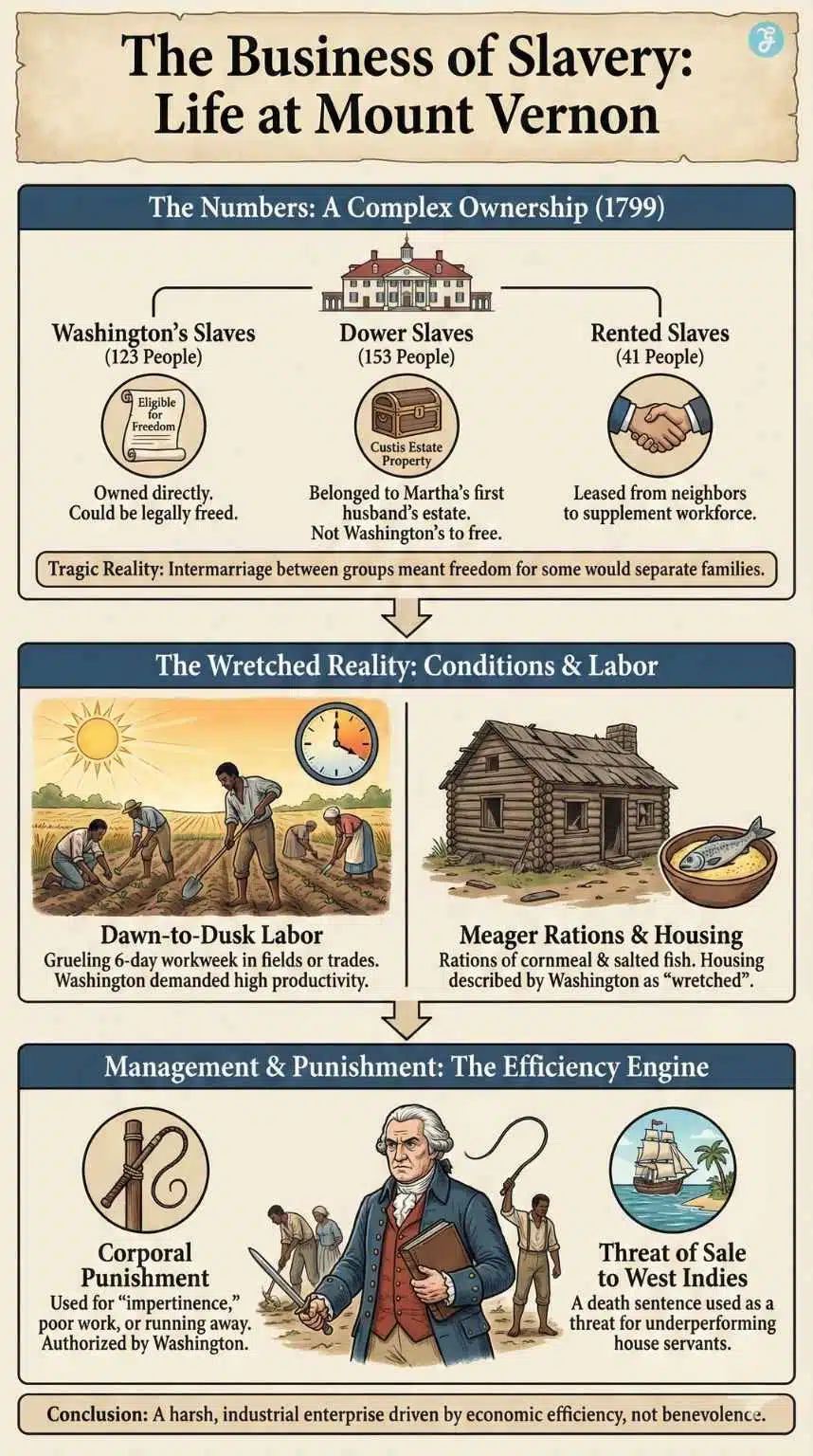

At the time of Washington’s death in 1799, the enslaved population at Mount Vernon stood at 317 people. However, Washington’s power to free them was limited by a complex legal web.

-

123 Individuals: These were “Washington’s slaves,” owned directly by him. He had the legal right to manumit (free) them.

-

153 “Dower” Slaves: These individuals belonged to the estate of Daniel Parke Custis, Martha Washington’s first husband. George Washington managed them and profited from their labor, but he did not own them. By law, they were destined to pass to Martha’s grandchildren.

-

41 Rented Slaves: These were rented from neighbors to supplement the workforce.

This distinction created a tragic human puzzle. Over the decades, Washington’s slaves had intermarried with the “dower” slaves. Any attempt to free his own workforce would inevitably rip families apart, leaving husbands free while their wives and children remained enslaved on the same property.

The “Wretched” Reality Behind “Benevolent” Myths

Some narratives try to soften slavery at Mount Vernon by hinting that Washington was a “kind” enslaver. But slavery cannot be separated from its structure: forced labor, lack of consent, family vulnerability, and punishment backed by law and violence.

Washington was a demanding businessman. He viewed the enslaved community as a machine that required constant calibration. He kept meticulous records of productivity and was often frustrated when output did not meet his high standards.

Life for the enslaved was grueling. Field workers labored from dawn until dusk, six days a week. Washington provided rations that were meager at best—mostly cornmeal and salted fish—and housing that he himself described in a letter as “wretched” log cabins with mud floors and no glass in the windows.

While Washington is often cited as a “mild” slaveholder because he discouraged the “passion” (anger) of overseers, he was not hesitant to authorize punishment. He utilized a whipping post for those who ran away or were deemed “impertinent,” and he frequently threatened to sell underperforming house servants to the West Indies—a death sentence due to the brutal conditions of sugar plantations.

Their work could be reassigned. Their families could be separated. Their bodies and time were not their own. Even when certain individuals held skilled positions or worked in the mansion, they remained legally property—subject to being sold, transferred, or inherited.

Fact Check: The Teeth and the Trade

One of the most persistent myths in American history is that George Washington had wooden teeth. The truth is far more unsettling and reveals the dark intimacy of slavery.

Washington suffered from dental problems his entire life, and by the time he became President, he had only one natural tooth left. His dentures were not made of wood, which would have rotted quickly. Instead, they were complex contraptions crafted from hippopotamus ivory, gold, lead, and human teeth.

Where did these human teeth come from? Mount Vernon’s own ledgers provide the answer. In May 1784, the account books record a payment of 6 pounds and 2 shillings to “Negroes for… 9 teeth.” It was common practice in the 18th century for dentists to purchase healthy teeth from the poor or enslaved to use in dentures for the wealthy. While the transaction was recorded as a “purchase,” the power dynamic of slavery makes the concept of a voluntary sale impossible to verify.

This detail challenges the sanitized version of history. It serves as a visceral reminder that the bodies of the enslaved were often viewed merely as resources—commodities to be used for labor, profit, and even the personal comfort of their owners.

The Political Evasion: The Pennsylvania Loophole

Perhaps the most damaging evidence against George Washington regarding his moral stance on slavery comes from his time as President in Philadelphia. This chapter of his life reveals a calculated effort to circumvent the law to protect his property interests.

In 1780, Pennsylvania passed the Gradual Abolition Act. This progressive law stated that any enslaved person brought into the state by a non-resident would automatically become free if they resided there for six continuous months.

The Rotation Scheme

Washington, serving as President in Philadelphia, was terrified of losing his enslaved staff, including his skilled chef Hercules and Martha’s personal maid, Oney Judge. To evade the law, he devised a secret rotation scheme.

Every six months, just before the legal deadline, Washington would transport his enslaved servants back to Mount Vernon or across state lines to New Jersey. This effectively “reset the clock” on their residency, ensuring they never reached the six-month threshold required for freedom.

The intent was not accidental. In a letter to his secretary, Tobias Lear, Washington gave explicit instructions to move the slaves “under the pretext that may deceive both them and the Public.” He knew that if the enslaved people discovered their rights under Pennsylvania law, they might sue for freedom—a political scandal he was desperate to avoid.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793

Washington also signed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, strengthening slaveholders’ ability to pursue and reclaim freedom-seekers across state lines. This was federal power used in defense of slavery, not against it.

For many people looking for a clean redemption arc—“Washington realized slavery was wrong and corrected it”—this is the hard fact that complicates the story. In the office, Washington helped stabilize the legal order that protected slaveholding.

The Resistance: Those Who Challenged Washington Directly

The narrative of George Washington often centers on his power, but the stories of those who resisted him are equally vital. Despite the risks, several enslaved people seized their own liberty, challenging the President’s authority.

The Chase for Oney Judge

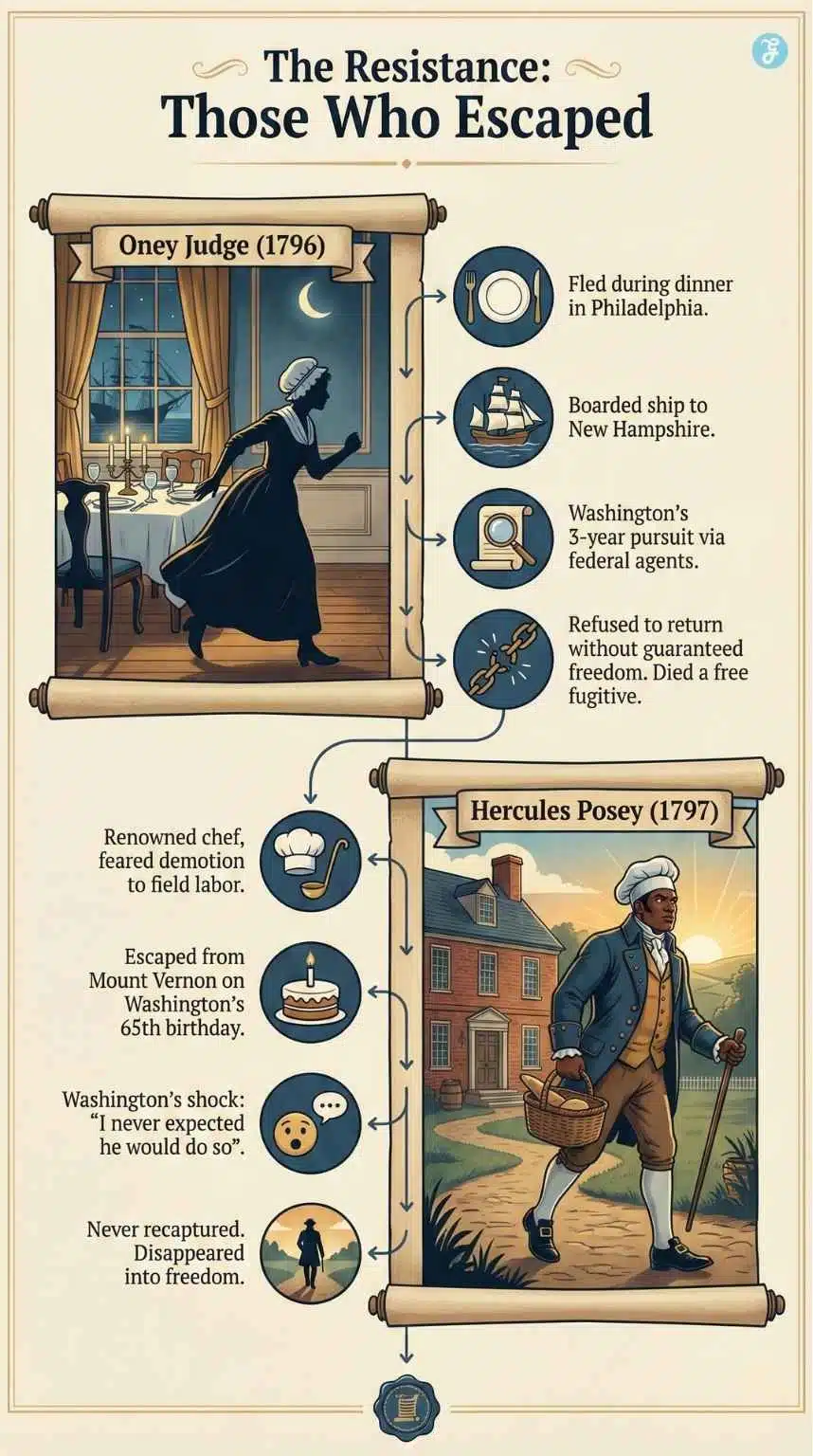

Oney Judge was Martha Washington’s body servant, a mixed-race woman who was highly skilled in sewing. In 1796, upon learning she was to be given away as a wedding gift to Martha’s granddaughter (who was known to be temperamental), Oney fled. While the Washingtons ate dinner in Philadelphia, she slipped out of the house and boarded a ship to New Hampshire.

Washington’s reaction was not one of resignation. He spent the last three years of his life aggressively pursuing her. He utilized the power of the federal government, asking the Secretary of the Treasury and the customs collectors to track her down.

When agents finally located her, Oney Judge made a stunning counteroffer: she would return only if the Washingtons promised to free her after their deaths. Washington refused to negotiate. He wrote that acceding to her demands would be “unfaithful” to the institution of slavery and reward a “breach of contract.” Oney Judge refused to return and died a free woman, though she lived her life as a fugitive.

Hercules Posey: The Celebrity Chef

Hercules was a figure of renown in Philadelphia. As Washington’s head chef, he was known for his culinary mastery and his impeccable dress. Washington allowed him to sell leftovers from the kitchen, giving Hercules a degree of financial independence and status.

Yet, status was not freedom. On Washington’s 65th birthday in 1797, Hercules was left at Mount Vernon while the family celebrated. Sensing that he might be demoted to a laborer in the fields, Hercules escaped. Washington was shocked, writing, “I never expected he would do so.” Despite extensive searches, Hercules was never recaptured.

Washington’s Views on Slavery: The Evolution of Conscience

It would be inaccurate to say George Washington remained stagnant in his views. Unlike many of his Virginian peers who defended slavery as a “positive good,” Washington’s perspective evolved, largely influenced by the Revolutionary War.

The Impact of War

During the Revolution, Washington commanded Black soldiers. Seeing African American men fight and die for the cause of American independence exposed the hypocrisy of his own position. How could a nation founded on the premise that “all men are created equal” continue to hold men in chains?

Private Regret, Public Silence

In the years following the war, Washington’s private correspondence began to change. He wrote to friends that he wished to “get quit” of slavery. He acknowledged that the system was economically inefficient and morally problematic. He expressed support for a gradual, legislative end to the practice.

However, his public actions did not match his private misgivings. Washington prioritized the stability of the fragile new Union above all else. He feared that taking a public stand against slavery would alienate the southern states and tear the nation apart. He signed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which gave slaveholders the legal right to cross state lines to capture runaways—a law that directly enabled the pursuit of people like Oney Judge.

The Final Act: The Will and Emancipation

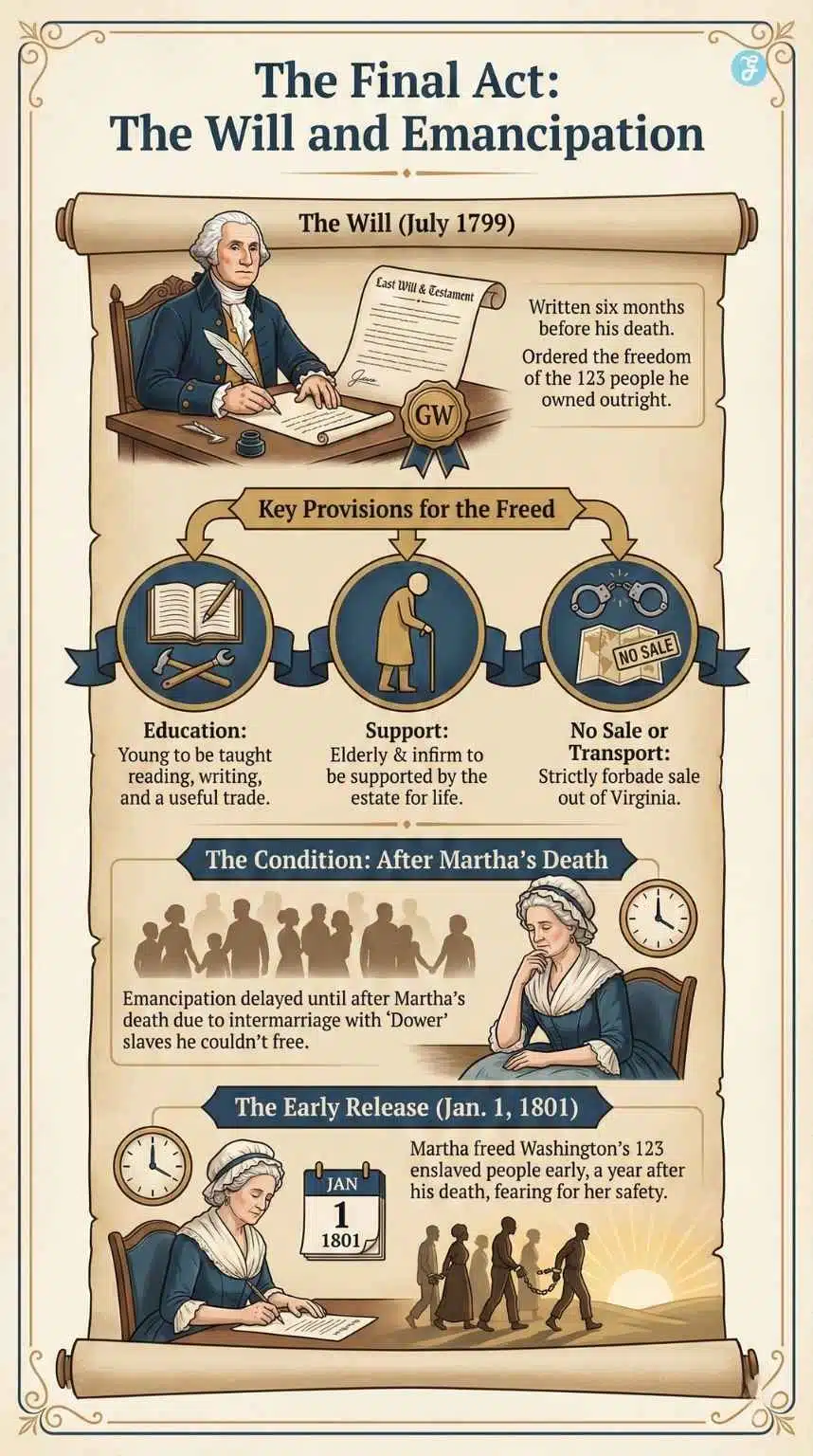

In the summer of 1799, six months before his death, George Washington sat down in his study to write his Last Will and Testament. In this document, he did something that no other slaveholding Founding Father—not Thomas Jefferson, not James Madison—would ever do.

Breaking the Chains

Washington ordered that all 123 enslaved people he owned outright be freed. He included specific provisions to ensure their well-being.

-

Education: Young freed people were to be taught reading, writing, and a useful trade.

-

Support: The elderly and infirm were to be supported by his estate for the rest of their lives.

-

No Sale: He strictly forbade the sale or transportation of any of his enslaved people out of Virginia.

The Timing

Washington stipulated that the emancipation should take place after the death of his wife, Martha. This decision was likely practical rather than cruel because of the intermarriage between his slaves and the “dower” slaves (whom he couldn’t free); immediate manumission would have caused social chaos at Mount Vernon.

However, Martha Washington did not wait. Terrified of living among people who had a direct financial interest in her death, she signed the order to free Washington’s slaves on January 1, 1801, a little over a year after his funeral.

The Aftermath: Freedom for Some, Fragmentation for Many

While Washington’s will is often celebrated as a grand gesture of emancipation, the story did not end happily for everyone at Mount Vernon. The “true story” contains a heartbreaking final chapter involving the “Dower” slaves—the 153 people owned by the Custis estate whom Washington could not legally free.

For decades, the two groups of enslaved people—Washington’s and the Dower slaves—had lived, worked, and married together. They had formed a singular community.

The Separation: When Martha Washington died in 1802, the Dower slaves were divided among her four grandchildren. This legal division shattered the Mount Vernon community.

-

Husbands and Wives: Freed men (former slaves of George) often had to watch helplessly as their wives (Dower slaves) were packed up and moved to different plantations.

-

Parents and Children: Families were split apart based on inheritance laws rather than human bonds.

A visitor to Mount Vernon during this time described the scene as one of “most poignant sorrow,” with people crying out as they were forcibly separated from their loved ones. While Washington’s will granted freedom to some, the entangled nature of slavery meant that liberty for one often came with the tragic loss of family for another.

How Should We Judge George Washington Today?

People often want a single verdict: Was Washington good or bad? History rarely offers such clean endings—especially with slavery. A more honest assessment is that Washington represented the founding era’s central conflict.

Such as:

-

He helped build a nation dedicated to liberty.

-

He personally profited from bondage and protected slavery’s legal security.

-

He expressed private hopes for slavery’s end, yet refused to wage a public fight against it.

-

He arranged emancipation for those he owned, but left many others still enslaved due to legal limits and choice.

Some view Washington’s will as evidence of moral growth rare among major Virginia slaveholders. Others argue that his “change” came too late and did too little—and that his presidential actions mattered more than private letters.

Both perspectives can be grounded in fact. The key is not to sanitize. The key is to tell the whole story.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did George Washington own enslaved people?

Yes. Washington owned enslaved people for most of his life and also controlled many more at Mount Vernon through the Custis dower estate connected to Martha Washington.

How many enslaved people lived at Mount Vernon?

By 1799, Mount Vernon held over 300 enslaved people. Not all were legally owned by Washington; many were dower slaves tied to the Custis estate.

Did Washington free his enslaved people?

In his will, Washington ordered the emancipation of the enslaved people he personally owned (with timing tied to Martha Washington’s death). The dower slaves could not be freed by his will.

Why is Ona Judge important in this story?

Ona Judge escaped from the Washington household in 1796 and refused to return. Her story shows enslaved people claiming agency and exposes Washington’s active efforts to preserve slavery in his own household.

Final Words: A Complex Legacy of George Washington

The story of George Washington and slavery is a testament to the complexity of the human condition. He was a man who built a nation on the promise of freedom while denying it to hundreds of people under his own roof. He was a harsh master who demanded total submission, yet he was also capable of the introspection required to eventually break the cycle.

We cannot sanitize Washington’s record, nor should we ignore his final act of redemption. He remains a paradox: the owner of human beings who became the father of a free country, and the only one of his peers who tried, at the very end, to make it right.

To confront this history is not to “tear down” the founding. It is to understand what was built, who paid the price, and why the unfinished struggle for equality did not begin later; it began at the beginning.