The fantasy of France reclaiming its scattered royal treasures persists, but the harsh reality is this: there is almost nothing to retrieve. A catastrophic revolutionary theft in 1792 and a deliberate state auction in 1887 have left the legendary French crown jewels legally sold, recut, or lost to history.

The question, “Can France retrieve its priceless crown jewels?” is not one of active diplomacy or legal battles, but rather a story of permanent loss. The jewels are not waiting in a vault to be reclaimed; they are either owned by private collectors and foreign museums or were destroyed centuries ago. This investigative report breaks down the two events that sealed their fate and the near impossibility of their return.

- The 1887 Sale: The French Third Republic sold the vast majority of the crown jewels in a public auction to prevent a royalist restoration. This was a legal, intentional act of state.

- The 1792 Theft: During the French Revolution, a massive heist at the Garde-Meuble (Royal Treasury) saw the theft of key gems, including the “French Blue” diamond, which was later recut into the Hope Diamond.

- What Remains: A core collection deemed “inalienable” (unsellable) was saved, including the 140.64-carat ‘Regent’ diamond. These are secure and on display in the Louvre’s Galerie d’Apollon.

- “Retrieval” is Repurchase: The only way for items to return is through repurchase at auction by the French state or private patrons, often at astronomical prices.

- Famous Buyer: American jeweler Tiffany & Co. was a major buyer at the 1887 sale, acquiring nearly a third of the lots and introducing major European gems to the American market.

A Crown Dispersed: The Two Events That Emptied the Treasury

To understand why retrieval is a phantom goal, one must look at the two definitive, catastrophic events that separated France from its jewels.

The 1792 ‘Theft of the Century’

The first blow came not from policy, but from chaos. In September 1792, with the monarchy abolished and the nation in turmoil, thieves broke into the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne (the Royal Treasury, now the Hôtel de la Marine) in Paris.

Over five nights, the thieves looted the collection. While many items were recovered in the following years (including the ‘Regent’ and ‘Sancy’ diamonds), the losses were staggering.

The most famous victim was the “French Blue” (or Bleu de France), a magnificent 69-carat blue diamond purchased by King Louis XIV. It vanished, only to resurface in London years later, having been recut into a smaller, 45.52-carat stone. Today, that gem is known as the Hope Diamond and rests permanently in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

- Statistic 1: The 1792 Heist: The theft included over 9,000 precious objects and gems, valued at an estimated 30 million francs at the time—a figure that would equate to hundreds of millions, if not billions, of dollars today.

Because the stolen gems, like the French Blue, were immediately recut, their original forms are lost forever. They cannot be “retrieved” because they no longer exist as they were.

The 1887 ‘Sale of the Century’

The second and final blow was self-inflicted. By 1887, the Third Republic was established, but fears of a royalist or Bonapartist coup lingered. The crown jewels were seen as a dangerous symbol of the monarchy.

To crush any royalist ambitions, the government made a pragmatic and ruthless decision: sell them.

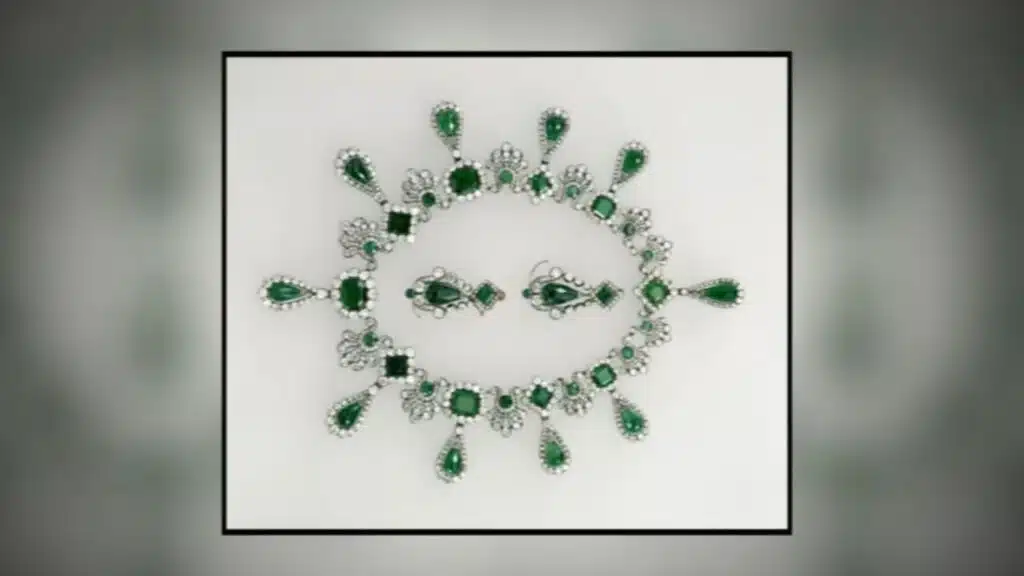

In May 1887, an auction titled “The Crown Diamonds of France” was held at the Louvre. It was a sensation. Jewelers from around the world, including Tiffany & Co., Bvlgari, and Boucheron, descended on Paris.

- Statistic 2: The 1887 Sale: The auction, which lasted 12 days, sold thousands of gems and objects. It raised approximately 7 million gold francs (sources vary slightly between 6.7 and 7.3 million), a sum equivalent to roughly $40-50 million USD today, though the intrinsic historical and brand value is now considered priceless.

Charles Lewis Tiffany famously purchased 24 lots, nearly one-third of the entire collection. This legal, public, and internationally-recognized sale permanently dispersed the collection. The jewels are now in private hands, museum collections (like the V&A in London), or have been broken up and resold countless times.

What Remains? The ‘Inalienable’ Treasures

Not everything was sold. The state, advised by the curators at the Louvre, set aside a core collection deemed to have priceless historical or mineralogical value.

These “inalienable” treasures, which cannot be sold by law, form the heart of the collection seen today in the Louvre’s Galerie d’Apollon. They include:

- The ‘Regent’ Diamond: A 140.64-carat cushion-cut diamond, considered one of the purest in the world. It famously adorned the hilt of Napoleon’s sword.

- The ‘Sancy’ Diamond: A 55.23-carat pale-yellow, shield-shaped diamond with a long, storied history.

- The ‘Côte-de-Bretagne’ Dragon: A 107.88-carat spinel (long thought to be a ruby) carved into the shape of a dragon.

These jewels are safe, secure, and not in need of “retrieval..

The Long, Faint Hope: Can France Retrieve Its Priceless Crown Jewels?

This is the central question, and the answer is a stark “no”—at least not through legal or diplomatic claims.

The Legal Impasse: Why the 1887 Sale is Final

The 1887 auction was not wartime looting. It was a legitimate, public sale by a sovereign government. The buyers hold clear, legal titles to their purchases. There is no international law or convention that would allow France to “reclaim” items it willingly sold.

Any attempt at “retrieval” would be an act of repurchase. The French state or its museums must enter the open market and bid like any other collector. This is where the challenge becomes financial.

Expert Analysis: A Collector’s Dream

The provenance of “From the French Crown Jewels” is one of the most desirable in the world, driving prices to astronomical levels.

François Curiel, Chairman of Christie’s Europe, has previously commented on the historic 1887 auction, noting its significance. While not a direct quote on retrieval, his analysis of the market highlights the challenge France faces. He stated in a 2018 Christie’s article that the 1887 sale “was a truly historic event... Today, finding a jewel with such a prestigious provenance is a collector’s dream.”.

This “dream” for collectors is a nightmare for a state budget. France must compete with the world’s billionaires to buy back its own history, one piece at a time.

Case Study: The Return of a Single Brooch

Occasionally, a piece does come back. But it illustrates the staggering cost.

In 2008, a magnificent diamond bow brooch, commissioned by Empress Eugénie from the jeweler Kramer in 1855 and sold in the 1887 auction, came up for sale at Christie’s.

- Statistic 3: The 2008 Repurchase: The Société des Amis du Louvre (Friends of the Louvre) successfully acquired the brooch for the museum. The price: 11.28 million Swiss francs (approx. $10.5 million USD at the time).

This was for one brooch. The cost to reassemble even a fraction of the 1887 collection would run into the billions.

A Legacy in Exile

It is, unequivocally, “too late” for France to retrieve its crown jewels in any comprehensive way. The 1792 theft mutilated the most ancient gems beyond recognition. The 1887 sale legally and permanently scattered the rest.

The “retrieval” of the French crown jewels is not an active campaign but a slow, incredibly expensive waiting game. It relies on the goodwill of patrons and the strategic budget of the Louvre to, piece by piece, buy back small fragments of a lost legacy when they surface at auction. The crown itself is gone; only the memory, and a few brilliant remnants, remain.

The Information is Collected from France 24 and BBC.