Canada’s push to build a “Canada Gulf Digital Services Corridor” is suddenly concrete: Ottawa has opened CEPA consultations with the UAE (ending Jan 27, 2026) while reactivating Saudi economic machinery and expanding air links. The prize is not oil, it is access to Gulf AI budgets, cloud buildouts, and government digital megaprojects.

Canada’s Gulf trade mission narrative is easy to misread as routine diplomacy. It is not. It is Ottawa placing a bet that the fastest, least tariff-exposed path to export growth in a fractured trading system is digitally delivered services and that the Gulf is becoming a high-spend, high-urgency buyer.

The timing matters. Canada’s services exports rose to $219.9 billion in 2024, and the digitally delivered portion of commercial services exports reached $70.3 billion in 2023, with 52% of commercial services exports delivered digitally. That is the macro backdrop: Canada already exports “invisible” value at scale, and the Gulf is building the infrastructure and regulation that turns big tech spending into recurring contracts.

What changed in late 2025 is that Canada’s Gulf strategy stopped being abstract and started looking like an integrated corridor plan:

- UAE as the dealmaking hub: investment, HQs, regional routing, and a potential CEPA that could harden digital trade rules.

- Saudi Arabia as the scale market: procurement-heavy demand, localization pressure, and large budgets tied to Vision-style transformation goals.

- Air connectivity as the enabling layer: more passenger capacity for deal teams and more cargo flexibility for high-value hardware and infrastructure supply chains that sit behind “digital services.”

How We Got Here: From Bilateral Trade To Corridor Architecture?

Canada-UAE ties are now being operationalized around trade rules and investment protections. Ottawa’s UAE CEPA consultations run December 13, 2025 to January 27, 2026, after leaders signaled intent to launch negotiations in 2026. The same consultation document also highlights the economic baseline: $3.4 billion in Canada-UAE merchandise trade in 2024 (Canada exports $2.6 billion, up 24% from 2023; imports $800 million), plus $388 million in bilateral commercial services trade in 2023. It also notes a capital story: UAE FDI in Canada at $8.8 billion (2024) and Canadian direct investment in the UAE at $242 million.

Saudi Arabia is being treated as the other anchor. In November 2025, Canada and Saudi Arabia announced the launch of negotiations for a Foreign Investment and Protection Agreement and reactivated a Joint Economic Commission. Trade numbers underscore why Riyadh matters: Canada-Saudi two-way merchandise trade was about $4.1 billion in 2024 (Canada exports $2.0 billion, imports $2.1 billion).

Then Ottawa added a practical accelerant: expanded air transport agreements. Canada’s UAE agreement now allows 35 passenger flights per week per country (an additional 14 per week) and unlimited all-cargo flights, with open fifth-freedom rights for all-cargo services. With Saudi Arabia, the agreement expands to 14 passenger flights per week per country (up from four) and unlimited all-cargo flights, also with open fifth-freedom cargo rights.

Milestones That Turn “Interest” Into A Corridor

| Date | Move | Why It Matters For Digital Services |

| Nov 6, 2025 | Canada-Saudi investment talks relaunched (FIPA negotiations, Joint Economic Commission) | Sets investment protection and problem-solving machinery for complex services deals |

| Nov 20, 2025 | Canada-UAE: intent to launch CEPA negotiations; FIPA signed | Anchors investor confidence and opens the door to digital trade provisions |

| Dec 1, 2025 | Canada expands air agreements with UAE and Saudi Arabia | Removes a real friction point: mobility for delivery teams, hardware, and partnerships |

| Dec 13, 2025 to Jan 27, 2026 | Canada’s UAE CEPA consultations | Defines Canada’s negotiating posture, including on digital trade rules |

Why The Canada Gulf Digital Services Corridor Is Taking Shape?

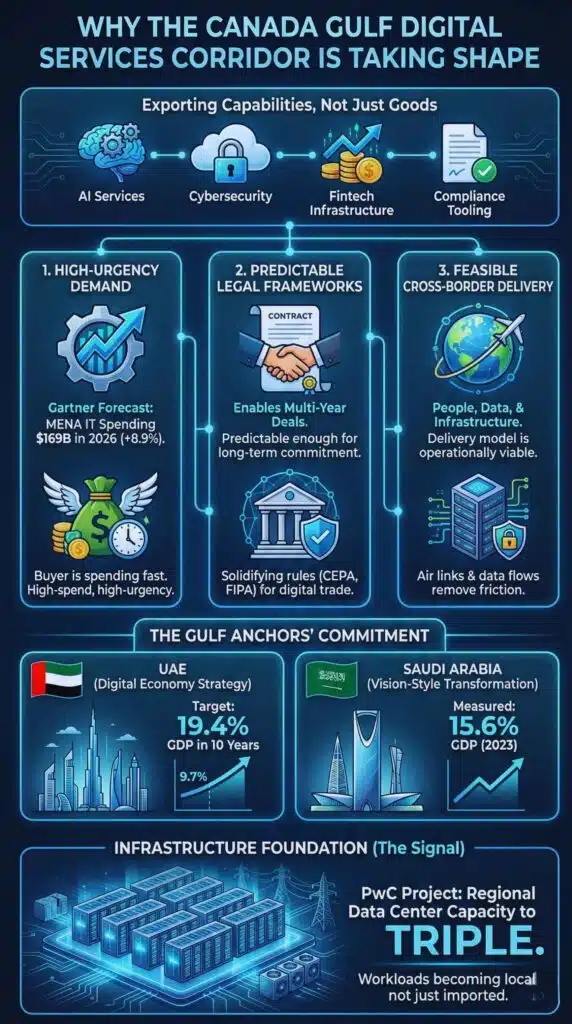

The corridor logic is not primarily about shipping more goods. It is about exporting capabilities: software, AI services, cybersecurity, fintech infrastructure, digital identity, data platforms, managed cloud, and compliance tooling. Those exports scale when three conditions align:

- The buyer is spending (and needs to spend fast).

- The legal framework is predictable enough to sign multi-year deals.

- The delivery model is feasible across borders (people, data, and infrastructure).

The Gulf increasingly checks all three. Gartner forecasts MENA IT spending at $169 billion in 2026, up 8.9% from 2025. On the supply side, the Middle East’s data center capacity is expected to surge. PwC projects regional capacity could triple to about 3.3 GW over five years, a signal that cloud and AI workloads are becoming local, not merely imported.

The UAE is explicit about where it wants to land: its Digital Economy Strategy targets doubling the digital economy’s GDP contribution from 9.7% (2022) to 19.4% within 10 years. Saudi Arabia is measuring similar momentum: its statistics authority reported the digital economy’s share of GDP rose to 15.6% (2023). In other words, both anchors are trying to institutionalize “digital” as a core economic engine, not an add-on.

UAE vs Saudi Arabia: Corridor Roles In Practice

| Corridor Function | UAE Often Plays | Saudi Arabia Often Plays | What A Canadian Firm Typically Does |

| Regional HQ and contracting hub | Strong | Growing | Base regional leadership in UAE; create Saudi entity for procurement-heavy work |

| Government-scale digital procurement | Moderate | Very high | Use UAE as launchpad, then localize delivery to meet Saudi requirements |

| Data and cloud ecosystem | Fast, internationalized | Fast, increasingly localized | Architect “dual-region” deployments and compliance controls |

| Capital and partnerships | High deal velocity | High scale, policy-led | Use UAE capital networks and Saudi project pipelines together |

Demand Signals: The Gulf Is Buying AI, Cloud, And Security At Industrial Scale

A “digital services corridor” only works if there is sustained demand that justifies localization costs, compliance overhead, and long sales cycles. Several indicators suggest the Gulf demand cycle is structural, not temporary:

- Saudi ICT market size: the Saudi regulator reported the ICT market reached SAR 166 billion in 2023 (with a multi-year growth profile).

- Saudi cybersecurity market: a National Cybersecurity Authority-linked analysis values the market at SAR 13.3 billion, with government a meaningful buyer and the private sector the larger share.

- Regional IT spending: the MENA region is forecast to keep growing IT spending through 2026, with AI infrastructure upgrades reshaping budgets.

- Data center buildout: a multi-year boom that converts capex into recurring cloud and managed-services demand.

This is why “corridor” is a better frame than “mission.” Missions end. Corridors compound. They create repeatable paths for procurement, talent deployment, and cross-border delivery.

Where The Spending Concentrates?

| Indicator | UAE Signal | Saudi Arabia Signal | Why It Matters To Canadian Exporters |

| IT spending trajectory | Rapid adoption and platform building | Massive transformation budgets | Supports multi-year managed services, not one-off projects |

| Digital economy targets | 19.4% of GDP within 10 years (target) | Digital economy at 15.6% of GDP (measured) | Political commitment reduces risk of demand collapsing |

| ICT market size | High per-capita spend | SAR 166B ICT market (2023) | Large addressable market for systems integrators and SaaS |

| Cybersecurity | Heavy regulation and compliance needs | SAR 13.3B cyber market | Creates demand for governance, risk, compliance, and SOC services |

The Corridor’s Hidden Constraint: Localization Rules And Procurement Reality

If the opportunity is real, the constraint is equally real rules. Saudi Arabia’s “regional headquarters” (RHQ) policy environment is a particularly important piece of the corridor puzzle. Starting January 1, 2024, Saudi Arabia moved toward restricting government contracting with foreign firms that lack a regional headquarters in the Kingdom. Over time, this pushes multinationals and service providers to do more than sell into Saudi Arabia. They must operate there.

That shifts the corridor strategy from “Dubai-and-fly-in” to “Dubai-and-Riyadh as a two-node operating model.” The UAE remains attractive for regional management, finance, and partnership networks. Saudi Arabia becomes non-optional for large public sector and quasi-public sector work.

On the Canadian side, the key point is not whether localization is “good” or “bad.” It is that it changes the unit economics:

- Higher upfront cost (entity setup, hiring, compliance).

- Higher contract value potential (government-scale deals, multi-year programs).

- Higher reputational and legal exposure (data, cyber, and content compliance).

What Procurement And Localization Typically Demand?

| Requirement Type | What Buyers Commonly Ask For | Why It Can Block A Deal | Practical Response For Exporters |

| Local presence | Registered entity, local staff, local leadership | Disqualifies firms at bid stage | Build a phased localization plan tied to revenue milestones |

| Data controls | Clear data residency, access, audit rights | Creates uncertainty for cloud-native delivery | Use regional cloud, encryption, logging, and documented governance |

| Cyber compliance | Evidence of controls, incident response, third-party risk | Buyers fear systemic risk | Lead with certifications, audit trails, and measurable SLAs |

| Subcontracting rules | Local partners and value transfer | Limits pure “remote delivery” | Build partner ecosystems early, not after winning bids |

Infrastructure Is Becoming The New Trade Policy

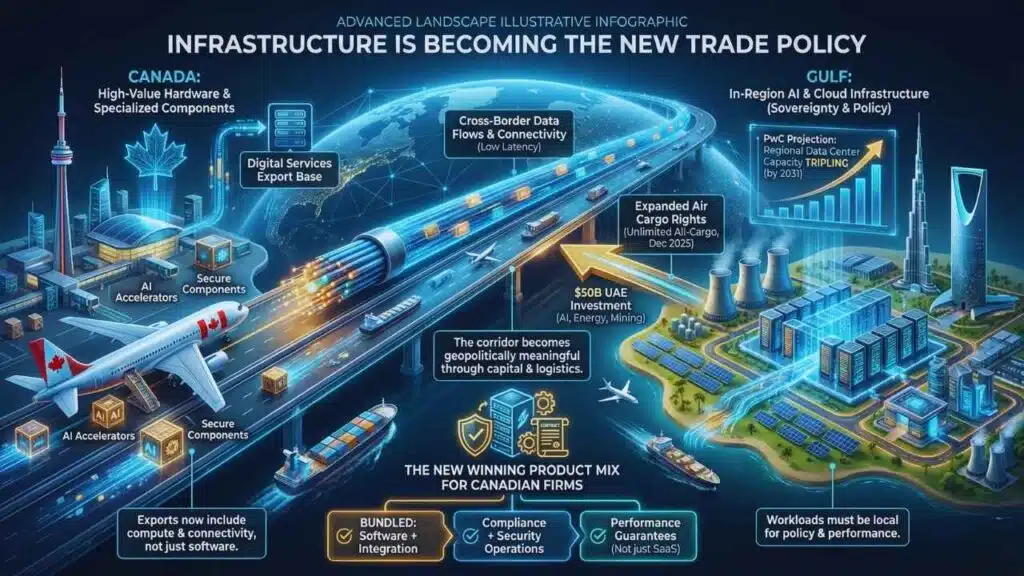

Digital services used to be mostly about software and people. In 2026, they are also about compute, data centers, and connectivity. This is where the corridor becomes geopolitically meaningful.

- The UAE has signaled ambitions to build large-scale AI infrastructure, and it has announced plans to invest up to $50 billion in Canada across sectors including AI, energy, and mining. This matters because it ties digital services to capital flows and to strategic industrial priorities.

- PwC’s projection of regional data center capacity tripling is not a niche statistic. It implies that “where workloads run” is being rewired, and contracts will increasingly require in-region deployments for latency, sovereignty, or policy reasons.

- Expanded air cargo rights may sound unrelated to cloud. In practice, it supports the movement of the high-value hardware and specialized components that sit behind AI infrastructure and secure networks.

For Canadian firms, the infrastructure shift changes the product mix that wins. “Nice-to-have” SaaS is not enough. The market pulls for offerings that bundle software with integration, compliance, security operations, and performance guarantees.

The Infrastructure Indicators That Change Deal Design

| Indicator | What Is Changing | What It Does To Service Contracts |

| MENA IT spending forecast ($169B in 2026) | AI and cloud are becoming budget priorities | Increases demand for migration, modernization, AI enablement services |

| Data center capacity projected to triple | Workloads localize | Pushes vendors to offer in-region hosting and support |

| Unlimited all-cargo and fifth-freedom cargo rights | Logistics options expand | Reduces friction for infrastructure-heavy projects |

| Digitally delivered services growth (Canada) | Canada’s export base is already digitalizing | Makes services, not goods, the scalable diversification lever |

Data Governance: The Make-Or-Break Layer For Cross-Border Digital Trade

A corridor that moves digital services must also move data. That is exactly where trade policy is most fragile. OECD analysis frames cross-border data flows as the “lifeblood” of modern economic activity, while also noting why governments regulate them: privacy, national security, cybersecurity, and concerns about regulatory reach. A joint OECD-WTO report on the economic implications of data regulation highlights the tradeoffs between openness and trust, and why convergent solutions matter.

This is where a Canada-UAE CEPA becomes more than tariffs. A modern CEPA can, in principle, shape:

- Cross-border data flow commitments (with exceptions).

- Data localization disciplines (with policy carve-outs).

- E-signatures, paperless trading, and digital identity provisions.

- Cyber cooperation and standards alignment language.

None of that guarantees market access, but it reduces the probability that a firm wins a deal and then loses it in implementation because the data architecture is non-compliant.

Common Data Questions Buyers Ask And What They Really Mean

| Buyer Question | What They Are Really Checking | Exporter “Proof” That De-Risks The Deal |

| “Where will the data be stored?” | Sovereignty, auditability | Data mapping, residency options, encryption design, access policies |

| “Who can access production data?” | Insider risk and compliance | Role-based access, logging, privileged access management |

| “Can you meet sector-specific rules?” | Readiness for regulated industries | Sector controls library, prior audits, documented controls-by-design |

| “How do you handle incidents?” | Operational maturity | IR playbooks, escalation SLAs, tabletop exercise evidence |

Expert Perspectives: Two Competing Readings Of The Corridor

A serious analysis needs to hold two ideas at once this corridor is a real opportunity, and it is not a guaranteed win.

One camp sees Canada’s Gulf push as smart diversification in a world where goods trade is vulnerable to tariffs, chokepoints, and industrial policy. Services, especially digitally delivered services, are harder to tariff and easier to scale.

The skeptical camp argues that Gulf markets are competitive, relationship-driven, and increasingly localization-heavy. Margins can compress under systems-integrator pricing pressure, and policy shifts can create sudden compliance costs. For many firms, the corridor only works if they commit to a multi-year presence and accept that “exporting” increasingly means “operating.”

Both can be true. The corridor may not be a shortcut. It is a longer runway that can produce larger contracts for firms that treat market entry as a capability build, not a sales trip.

Optimistic vs Cautious Interpretations

| View | Core Claim | What Would Prove It Right In 2026 |

| Corridor Optimists | CEPA + investment protection + connectivity lowers friction and unlocks services exports | Early 2026 deals, repeatable procurement pathways, clear digital provisions in negotiation mandates |

| Corridor Skeptics | Localization and compliance will limit who can profitably play | Rising bid costs, forced local hiring, slower deal cycles, margin compression |

| Pragmatists | The winner is the firm that productizes compliance and delivery | More “managed” offerings, stronger partner ecosystems, and dual-node delivery models |

What Happens Next: The 2026 Milestones That Will Decide Whether This Is Real?

The next phase is not rhetorical. It is procedural and commercial. Watch these milestones:

- Jan 27, 2026: UAE CEPA consultation closes. The submissions will shape Canada’s negotiating posture, including any digital trade priorities.

- Early 2026: Canada’s trade minister is expected to lead a high-level business delegation to the UAE focused on sectors including AI and ICT. That matters because partner selection happens before procurement, not after.

- CEPA negotiation launch in 2026: the first rounds will signal whether digital trade is central or cosmetic.

- Saudi investment negotiations and joint commission activity: if these mechanisms begin producing commercial problem-solving, the Saudi leg of the corridor becomes more investable for mid-sized exporters.

- Delivery architecture decisions: firms will choose between “UAE-only” approaches and dual-node operations that meet Saudi localization realities.

2026 Watchlist Timeline

| Window | Watch Item | Why It Matters |

| January 2026 | UAE CEPA consultations end (Jan 27) | Locks in what Canada will prioritize in negotiations |

| Q1 to Q2 2026 | Trade mission and deal pipeline formation | Determines which Canadian firms enter partnerships early |

| 2026 (Negotiation period) | Scope of digital trade provisions | Influences data, cloud, and e-commerce certainty |

| 2026 onward | Localization and delivery footprints | Separates “exporters” from “operators” in Gulf markets |

The corridor will reward Canadian companies that treat the Gulf as a delivery market, not just a sales market. The likely winners are those that combine (1) strong technical offerings with (2) compliance-by-design and (3) credible localization plans that do not destroy unit economics. If Canada’s CEPA approach with the UAE elevates digital trade rules and investment certainty, it can reduce friction for hundreds of firms, but it will not replace the hard work of operating inside Gulf procurement ecosystems.