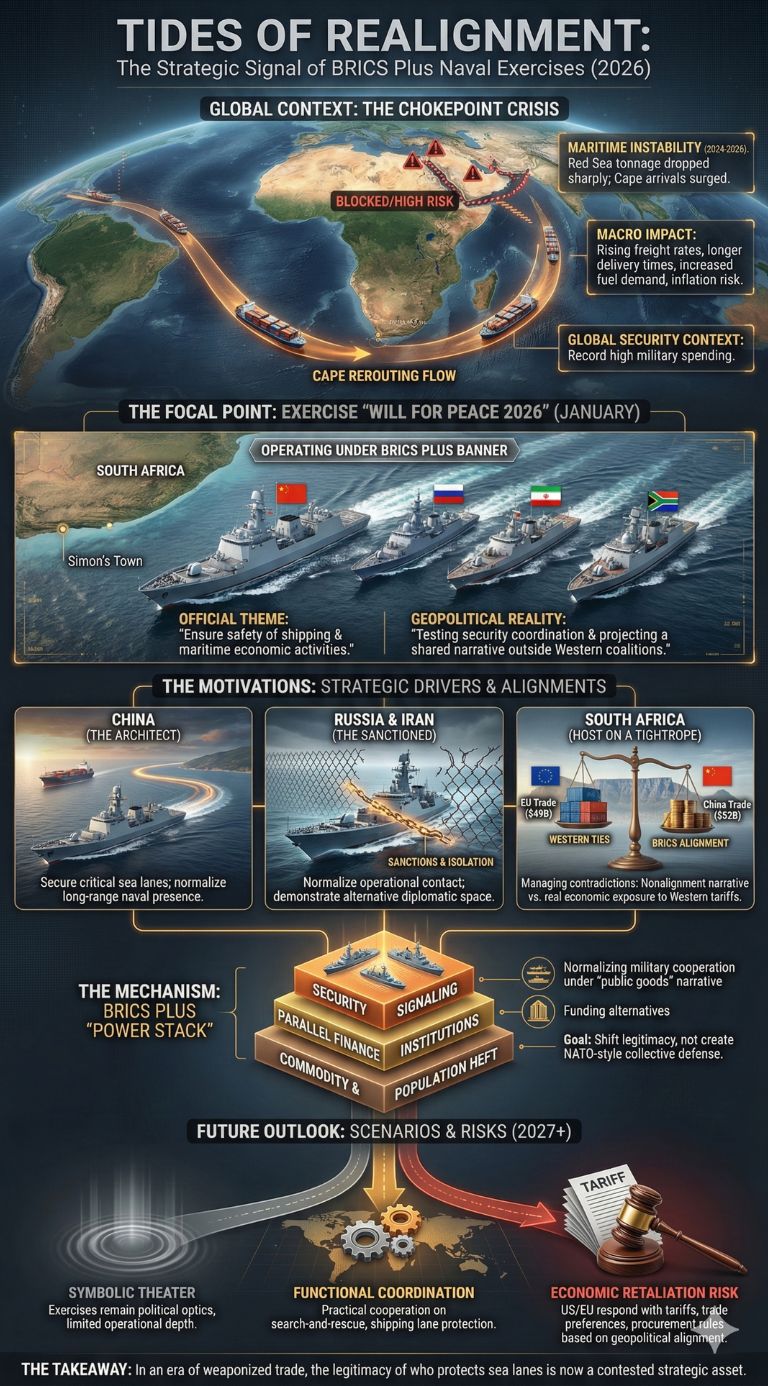

BRICS Plus naval exercises off South Africa are more than a routine drill. They signal a bloc testing security coordination as sea-lanes destabilize, tariffs rise, and the Global South rebalances power in 2026 faster than expected. What happens next could reshape trade routes, sanctions, and alliances.

South Africa’s “Exercise Will for Peace 2026,” running in early January, sits at the intersection of two storylines that usually get covered separately: the slow build of BRICS as a political economy coalition, and the fast-moving insecurity of global maritime trade. The drill’s official framing is telling. South Africa’s government describes the exercise as a joint effort “to ensure the safety of shipping and maritime economic activities,” a phrase that reads like a technical mission statement but functions like a geopolitical argument.

That argument matters because it arrives at a moment when “shipping security” is no longer a neutral concept. After months of rerouting around the Cape of Good Hope due to Red Sea risks, maritime chokepoints are now a core macroeconomic variable, influencing delivery times, freight rates, insurance premiums, fuel demand, and even inflation trajectories. International trade bodies have quantified the disruption: tonnage through the Gulf of Aden and Suez-linked lanes fell sharply during the peak of the crisis period, while Cape arrivals surged as carriers diverted.

Against that backdrop, the visible presence of China, Russia, and Iran with South Africa under a BRICS Plus banner lands as more than symbolism. It is a test of whether a bloc designed for economic coordination can start projecting a shared security narrative, even if it remains far from a formal alliance.

How BRICS Plus Reached This Moment

BRICS began as an economic shorthand and evolved into a political platform. Its “plus” expansion is now its main strategic story: more members, more commodity heft, more voting blocs in multilateral forums, and a larger audience for a “multipolar” worldview. BRICS’ own official materials emphasize scale and a widening membership list that now includes Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the UAE, Ethiopia, Indonesia, and Iran.

Scale, however, creates a new challenge: coherence. BRICS was never built like NATO or even the EU. It has no mutual defense clause, no integrated command structure, and no single threat perception. That is why military exercises matter analytically. They can function as low-commitment coordination that still produces real strategic messaging: who is seen training with whom, where, and under what stated purpose.

South Africa’s drill also sits in a longer timeline of naval cooperation among a subset of BRICS members. Prior iterations featured South Africa, China, and Russia. The 2026 iteration is notable because it is explicitly framed as “BRICS Plus,” includes Iran, and is widely reported as being led by China.

In other words, even if BRICS as a whole remains heterogeneous, a smaller cluster inside BRICS Plus is experimenting with security signaling.

| Element | What’s Publicly Reported Or Announced |

|---|---|

| Name | Exercise Will for Peace 2026 |

| Timing | 9–16 January 2026 |

| Location | South African waters, commonly linked to Simon’s Town and nearby operating areas |

| Official Theme | Joint actions to ensure the safety of shipping and maritime economic activities |

| Lead | Widely reported as China-led |

| Participants | South Africa, China, Russia, Iran |

| Wider Context | Framed under BRICS Plus amid ongoing BRICS expansion debate |

From Economic Bloc To Security Signaling

BRICS’ central pitch has long been institutional reform: a larger role for emerging economies, more South-South trade, and greater autonomy from Western-led structures. But in 2026, three forces are pushing BRICS discourse toward security-adjacent territory.

First, sanctions have become a structural feature of the global economy. Russia is the clearest case, but Iran is foundational to the sanctions era too. When sanctioned states join drills with key emerging-market players, they test the edges of diplomatic isolation and normalize operational contact.

Second, trade policy has re-hardened. Public reporting has described U.S. threats to impose major tariffs tied to perceived efforts to weaken dollar dominance, reflecting how economic policy is increasingly used for geopolitical leverage.

Third, maritime security is now tied to consumer prices and corporate supply chains. That makes naval capability and maritime diplomacy more relevant to “economic blocs” than it would have been in a lower-friction globalization era.

The significance of “Will for Peace” is not that BRICS is becoming a military alliance overnight. The significance is that BRICS Plus members are learning how to wrap military cooperation inside an economic-security narrative that resonates with the lived reality of 2024–2026 supply chain volatility. Trade institutions have increasingly framed chokepoint vulnerability as a strategic concern rather than a purely operational problem.

Key Statistics That Explain Why Shipping Security Became Political

-

Trade monitors reported extreme reductions in Red Sea related corridors at crisis peaks, including steep drops in Gulf of Aden and Suez-linked flows, paired with a large rise in Cape rerouting.

-

Route changes increased average distances traveled, raising ton-mile demand and compounding capacity pressure.

-

Major carriers began selective, risk-managed returns to parts of the Red Sea route in late 2025, signaling partial normalization while uncertainty remains.

-

Global military spending reached record levels in 2024, reinforcing that the wider security environment is not cooling.

Sea Lanes, Chokepoints, And Why South Africa’s Waters Matter Again

A decade ago, naval drills near South Africa would have looked like regional defense diplomacy. In 2026, geography turns them into a commentary on the world economy.

The Cape of Good Hope has regained strategic centrality because it is the viable detour when the Red Sea corridor becomes too risky. That detour is costly, but it is also stabilizing: it keeps trade moving, even if it raises ton-mile demand and lengthens delivery times.

Energy markets also feel the security shock through bunker fuel demand and tanker routing. Longer routes reshape fuel demand patterns, raise voyage costs, and push up logistics friction across commodity chains that used to rely on tighter transit times.

This is the strategic opening BRICS Plus exploits with its messaging. “Safety of shipping” is not only a naval concern anymore. It is a macro concern. And when major powers and sanctioned states participate in drills under that banner, they implicitly argue that Western-led naval coalitions are not the only route to maritime stability.

| Indicator | Direction Of Change (As Reported) | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Suez-linked transits and tonnage | Fell sharply during peak disruption periods | Raises costs, extends supply chains, hits Europe–Asia delivery reliability |

| Gulf of Aden flows | Dropped heavily at crisis peaks | Signals risk avoidance and higher insurance and security costs |

| Cape rerouting | Rose strongly as ships diverted | Re-centers South African waters as a global trade artery |

| Partial normalization signals | Select carriers tested limited returns | Markets must price both “risk persists” and “routes normalize” scenarios |

South Africa’s Strategic Tightrope: Nonalignment Meets Real Exposure

South Africa is not only hosting ships. It is managing contradictions.

On one side is the nonalignment narrative: South Africa can argue that maritime drills are routine, that it engages multiple partners, and that “shipping safety” is a global public good. Its official language leans into that technocratic legitimacy.

On the other side is the reality of economic exposure to the West, especially via trade and investment relationships that are difficult to replace quickly. Official trade summaries show how material those ties remain. The EU remains a key trading partner by reported goods trade value, and U.S. goods trade with South Africa remains substantial.

Those figures matter because geopolitical positioning can trigger economic consequences that show up as tariffs, procurement restrictions, export controls, or investment chill. Later 2025 reporting described South Africa leaning harder toward economic collaboration with China following a sharp U.S. tariff hike on South African exports, illustrating how quickly trade becomes political when relationships sour.

Meanwhile, South Africa’s domestic politics complicate external messaging. Opposition criticism frames hosting sanctioned states’ forces as incompatible with genuine neutrality, turning foreign policy signaling into an internal contest over national interest and reputational risk.

So the analytical question is not whether South Africa “chooses BRICS over the West.” The more realistic question is whether South Africa can sustain a multi-vector policy while U.S. and European politics become less tolerant of ambiguity.

| Partner | Recent Reported Goods Trade Value | What It Suggests About Leverage |

|---|---|---|

| European Union | €49B in 2024 | EU remains a core market and an investment signal |

| United States | $26.2B in 2024 | Trade tools can create fast pressure |

| China | $52.46B in 2024 | China is the scale partner for commodities and manufacturing imports |

China, Russia, And Iran: Naval Diplomacy Under Sanctions Pressure

For China, Russia, and Iran, the value of the exercise is asymmetric.

China gets the image of leadership. The drill is widely reported as China-led and includes Chinese naval assets operating in the region. China’s broader interest is straightforward: secure sea lanes for trade, diversify partnerships, and normalize a presence that supports longer-term influence across the Indian Ocean and adjacent waters.

Russia’s value proposition is partly reputational. With the Ukraine war continuing to shape alignments, visible military cooperation outside Russia’s immediate neighborhood undercuts the narrative of isolation and demonstrates alternative diplomatic space. The drill also offers interoperability practice and port-access relationships that matter for a navy operating under sanctions constraints.

Iran’s participation carries a different signal. Iran has hosted comparable exercises with Russia and China in its own southern waters in recent years. Bringing that “maritime security” framing to South African waters extends Iran’s message that it can operate as a legitimate security actor in international waters, even while remaining a focal point of Western security concerns.

The important nuance is that these drills do not need to produce shared command structures to matter. In modern geopolitics, repeated contact, shared operational language, and reciprocal port calls can gradually thicken relationships that later become important during crises, including shipping disruptions, evacuation operations, sanctions enforcement conflicts, or arms transfer monitoring.

And the world is already trending toward higher defense activity. Record global military spending and the steepest annual rise in decades suggest the backdrop: security competition is not cooling.

BRICS Plus As A Power Stack: Money, Markets, And Institutional Spillover

A common Western critique of BRICS is that it is too diverse to become a meaningful counterweight. That critique is partly true in security terms, but incomplete in institutional terms.

BRICS does not need to become a unified military bloc to shift the global system. It can do so through a “power stack” of membership scale, commodity weight, voting coordination in global forums, and parallel financial capacity.

Think tank analysis on BRICS expansion emphasizes that the bloc’s appeal is partly rooted in size, population share, and economic weight under purchasing-power comparisons, even as internal contradictions remain.

This is where spillover institutions matter. The New Development Bank offers a concrete example of parallel capacity building. Public investor materials describe cumulative approvals in the tens of billions of dollars across well over 100 projects by end-2024, plus an active portfolio worth more than $35 billion. Even if this financial scale is still smaller than the World Bank or regional development banks, it supports a narrative of alternatives, especially for borrowers seeking diversified funding sources.

Why mention development finance in a naval-drill analysis? Because it shows BRICS’ broader strategy: build legitimacy through “public goods” language, including development, shipping safety, and infrastructure resilience, then use that legitimacy to resist external pressure tools like sanctions, tariffs, and conditionality.

Tariffs, Currency Politics, And The Next Phase Of Economic Statecraft

The drill’s geopolitical meaning sharpens under the shadow of tariff threats and currency politics.

Public reporting in 2025 documented warnings that BRICS-related moves away from the dollar could trigger very high tariffs, explicitly linking BRICS political economy rhetoric to U.S. trade retaliation. This matters because it changes incentives inside BRICS Plus.

For countries already subject to sanctions, tariff threats matter less than maintaining alternative trade channels and diplomatic partners. For countries deeply embedded in Western trade and finance, the cost of escalation is higher. For swing states, the game becomes hedging: gain leverage by signaling BRICS proximity while avoiding steps that trigger direct economic punishment.

South Africa sits squarely in that swing category. It has meaningful trade with the EU and U.S., and it also has a massive China trade relationship by value.

That makes the question “what comes next?” less about ideology and more about whether the global system becomes so conflictual that hedging itself becomes unacceptable. If major powers demand clearer alignment, symbolic actions like naval exercises become evidence in a broader case file.

Expert Perspectives And The Core Counter-Argument

A balanced analysis has to take seriously the counter-case: that naval drills are routine and overread.

There is a real risk of interpretive inflation here. Military exercises happen constantly. They can be scheduled long in advance, shaped by bureaucratic incentives, and designed for readiness rather than signaling. South Africa can plausibly argue it is conducting maritime cooperation aligned with shipping safety, which is a legitimate global interest.

Think tank analysis on BRICS expansion also stresses internal diversity. BRICS contains rivals and divergent political systems, and expansion increases the difficulty of unified policy. From that viewpoint, drills do not equal alliance, and BRICS Plus cannot easily coordinate hard-security objectives beyond surface-level cooperation.

But the counter-argument has its own blind spot: signaling does not require alliance. Modern geopolitics often runs on repeated, ambiguous actions that slowly shift expectations. The analytic question is not “Is BRICS NATO?” It is “Does BRICS Plus gradually normalize security cooperation under an economic-public-goods narrative, in ways that reduce Western monopoly over legitimacy?”

In a world where shipping disruption is measurable and persistent, that narrative can be influential because it connects directly to inflation, growth, and supply chain resilience.

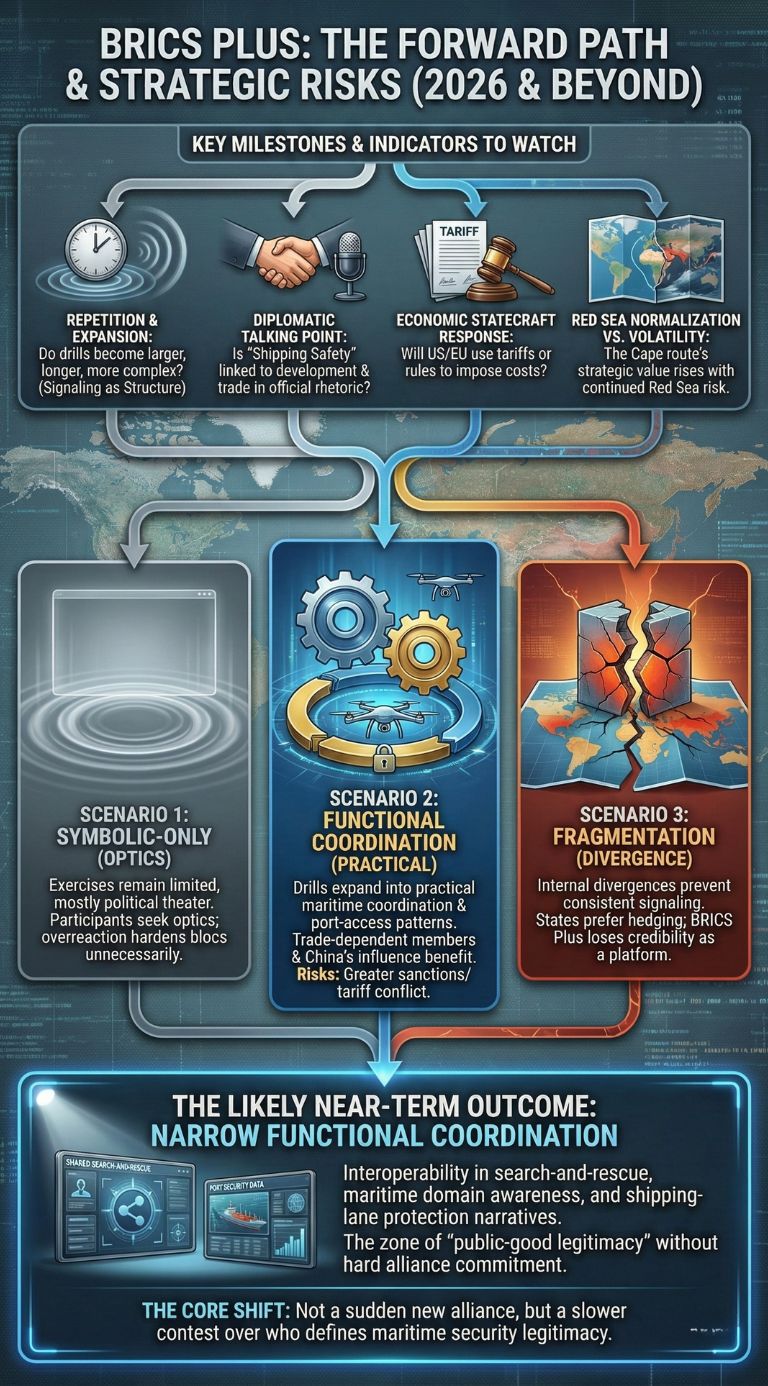

What Happens Next: Scenarios And Milestones To Watch

The forward-looking implication of “Will for Peace” is that it may be a prototype. The drill’s value is not its immediate tactical output, but its precedent-setting effect: a “BRICS Plus” label attached to security cooperation in a globally relevant maritime corridor.

What to watch in 2026 is less about one exercise and more about repetition, expansion, and institutionalization.

Milestones That Will Clarify Direction

-

Whether BRICS Plus repeats or expands joint drills, including new participants, longer duration, or more complex scenarios. Repetition is how signaling becomes structure.

-

Whether “shipping safety” becomes a standing BRICS Plus diplomatic talking point, linking maritime security to development and trade.

-

Whether the U.S. and EU respond through economic statecraft, including tariffs, trade preferences, and procurement rules, turning symbolic exercises into material costs.

-

Whether Red Sea routing normalizes or remains volatile, because the Cape route’s strategic value rises when the Red Sea remains risky.

| Path | What It Looks Like | Who Benefits Most | Primary Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symbolic-Only | Exercises continue but remain limited and mostly political theater | Participants seeking optics | Overreaction that hardens blocs unnecessarily |

| Functional Coordination | Drills expand into practical maritime coordination and port-access patterns | Trade-dependent members and China’s maritime influence | Greater sanctions or tariff conflict, higher insurance and routing costs |

| Fragmentation | Internal BRICS divergences prevent consistent security signaling | States preferring hedging | Credibility loss for BRICS Plus as a coherent platform |

The most likely near-term outcome is functional coordination in narrow areas like search-and-rescue interoperability, maritime domain awareness exchanges, and shipping-lane protection narratives. That is the zone where BRICS Plus can claim public-good legitimacy without committing to a hard alliance that many members would resist.

Final Thoughts: Why This Matters Beyond South Africa’s Coastline

The 2026 BRICS Plus naval exercises matter because they fuse three realities into one event: the weaponization of trade, the securitization of sea lanes, and the institutional ambition of the Global South.

If the 1990s model of globalization treated shipping routes as background infrastructure, the 2024–2026 era treats them as contested terrain. Documented rerouting and chokepoint disruption explain why. At the same time, the global rise in military spending underscores that states are investing in the capacity to operate in contested environments.

BRICS Plus is trying to translate that environment into political advantage. The “safety of shipping” framing gives it language that sounds non-ideological but carries deep strategic meaning. South Africa’s choice to host the exercise shows both the appeal and the risk of that strategy: it creates leverage and visibility, but also increases exposure to retaliatory economics in an era when tariffs and sanctions have become default tools.

What comes next is not a sudden new alliance system. It is a slower shift in legitimacy: who gets to define security, who gets to protect trade routes, and who pays the cost when geopolitics interrupts commerce. In 2026, that legitimacy contest may prove more consequential than the ships themselves.