In the lush landscapes of Bengal, where rivers bend gently through villages and forests whisper with mystery, a writer was born who would become the first eco-storyteller of Bengal. Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay (1894–1950) is remembered worldwide for his classic Pather Panchali, but his literary legacy goes far beyond one novel.

What sets him apart from many of his contemporaries is his deep, almost spiritual connection with nature. Long before terms like “eco-literature” or “climate fiction” became fashionable, Bibhutibhushan was weaving rivers, forests, and fields into his stories—not as backdrops but as living, breathing characters.

On his birthday, remembering Bibhutibhushan is not just a tribute to a novelist; it is an acknowledgment of a visionary who foresaw the importance of the bond between humans and the natural world.

The Life of a Nature-Bound Writer

Bibhutibhushan was born on 12 September 1894 in a small village in Nadia district. His childhood was shaped by poverty, but also by the beauty of rural Bengal. The rhythm of the seasons, the songs of rivers, and the fields swaying in the wind became the invisible teachers that nurtured his imagination.

The Writer Close to the Soil

Though he later moved to Calcutta for education, he never lost touch with his roots. His career as a teacher and later his job in the Gouripur Estate in Bihar exposed him to forests, rivers, and tribal life. These experiences would directly inspire some of his most celebrated works.

Nature in His Masterpieces

Pather Panchali—Nature as a Companion

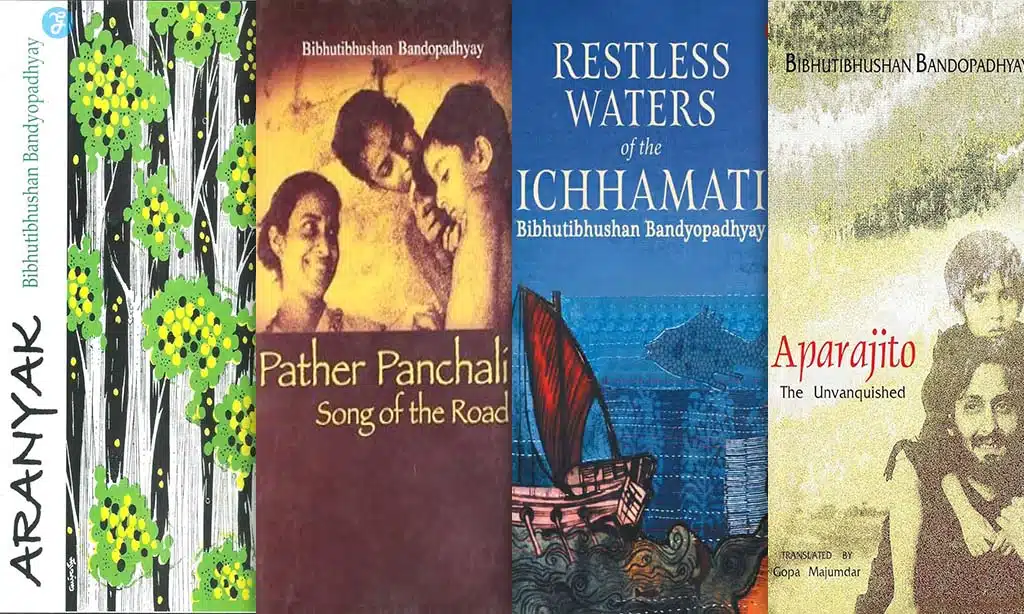

Published in 1929, Pather Panchali introduced readers to Apu and Durga, two siblings growing up in a poor rural family. But more than just a story of childhood, the novel painted a canvas of rural Bengal, where nature was inseparable from life.

The pond, the fields, the mango groves, the monsoon rains—all are described with such intimacy that they become characters themselves. Nature brings joy to the children, but it also brings hardship when floods and scarcity strike.

Aparajito—The Changing Bond

In the sequel Aparajito (1932), Apu grows up, leaves his village, and begins to see nature differently. The descriptions of landscapes now reflect both nostalgia and distance, showing how human relationships with the environment evolve over time.

Aranyak—The Forest Speaks

Perhaps Bibhutibhushan’s most explicitly ecological work, Aranyak (1939), was born out of his years working in Bihar’s forests. The novel is a lyrical meditation on wilderness—filled with vivid accounts of trees, rivers, and tribal communities.

Yet, it is not a romanticized fantasy. The book is also a critique of human greed, showing how forests are destroyed by landlords and settlers. Aranyak stands as an early environmental classic, warning us about the consequences of deforestation long before ecological debates became global.

Ichhamati—The River as Witness

Written near the end of his life, Ichhamati (1950) places the river Ichhamati at the center of the narrative. The river is not merely scenery; it is a silent witness to colonial exploitation, indigo plantations, and the everyday struggles of villagers. In Bibhutibhushan’s hands, the river becomes a metaphor for time, memory, and resilience.

Thematic Depth of His Nature Writing

Unlike many writers who use nature as a passive backdrop, Bibhutibhushan treats it as an active presence. His forests breathe, rivers speak, and fields hold secrets. Readers often feel that they are walking alongside him in a living world.

Harmony and Conflict

He does not shy away from portraying both sides of nature—its nurturing generosity and its unforgiving cruelty. In Pather Panchali, the same rains that bring beauty to the fields also bring despair through floods and disease. This duality makes his nature writing realistic and profound.

Human-Nature Bond

For Bibhutibhushan, human dignity and resilience often emerge through a connection with the land. His characters—from Apu to Shankar in Chander Pahar—find purpose in their relationship with nature, whether in rural Bengal or the distant landscapes of Africa.

Eco-Storyteller Ahead of His Time

In Aranyak, Bibhutibhushan directly confronted the issue of deforestation, showing how greed could destroy both forests and human lives. His awareness of ecological loss makes him one of the earliest literary voices to articulate environmental concerns in Indian literature.

Spiritual Ecology

His descriptions of forests and rivers are not just physical but also spiritual. Nature, for him, is tied to human morality and inner life. Reading his works often feels like entering a meditative space where nature becomes a guide to understanding existence itself.

Timeless Relevance

At a time when climate change and ecological destruction dominate global conversations, Bibhutibhushan’s works remain startlingly relevant. His novels remind us that literature has always been capable of teaching ecological responsibility—long before the modern environmental movement.

Legacy in Literature and Beyond

Writers like Sunil Gangopadhyay, Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay, and Buddhadeb Guha drew inspiration from Bibhutibhushan’s ecological sensitivity. His influence continues in modern Bengali fiction, where nature is still celebrated as a central theme.

Global Recognition through Cinema

Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy, based on Pather Panchali and Aparajito, brought Bibhutibhushan’s vision to the world stage. In these films, nature is not a backdrop but an active participant—a clear reflection of the novelist’s worldview.

Why We Must Read Him Today

Bibhutibhushan’s writing reminds us of a truth that is easy to forget in our urbanized, digital lives: humans are not separate from nature but part of it. His works call us to pause, to observe, and to reconnect with rivers, forests, and the soil that sustains us.

Takeaways

Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay was more than a storyteller; he was Bengal’s first eco-storyteller. His novels and stories transformed rivers into witnesses, forests into philosophers, and landscapes into eternal companions. At a time when the world is grappling with environmental crises, his works offer both solace and warning.

On his birthday, remembering Bibhutibhushan is more than paying tribute to a great novelist. It is a reminder that literature can awaken ecological awareness, nurture compassion, and teach us to live in harmony with the natural world. His pen showed us that nature is not silent—it speaks, it warns, and it inspires. And through his words, it will continue to do so for generations to come.