Modern dating apps use machine learning to predict compatibility. The AI dating algorithms analyze swipe patterns, conversation length, response rates, and profile engagement to build a model of what each user “wants”—and to surface matches that the algorithm believes will succeed. This works reasonably well when the user’s preferences are individual and self-contained: you like hiking, and they like hiking. You prefer tall partners; here are tall partners.

But South Asian matchmaking involves criteria that are communal, layered, and often unspoken. Family background. Regional origin. Caste (still, despite progressive intentions). Religious denomination. Linguistic compatibility. Socioeconomic parity. The approval of parents, siblings, and extended family. None of these variables are captured in a dating app’s standard interface. And when AI tries to learn South Asian preferences from behavioral data alone, it often gets the picture catastrophically wrong.

The question is no longer just “apps versus families.” It is “what happens when the algorithm tries to learn the culture?”

AI Dating Algorithms vs. Tradition: The Two Systems of Love

In a flat in East London, Fatima Chowdhury is doing something her grandmother would find bewildering and her mother would find offensive. She is swiping through Muzz, a Muslim-focused dating app, while eating her mother’s shatkora beef curry—the very dish that, in her mother’s generation, would have been served at a ghotkali, the formal meeting where two families would size each other up over dinner before deciding whether their children were a suitable match.

Fatima is 28, British-Bangladeshi, and a data analyst at a fintech startup, and she is caught between two systems of romantic selection that could not be more different. One is ancient, communal, and family-mediated. The other is algorithmic, individualistic, and entirely in her hands. Neither feels quite right. Both feel necessary.

“My parents met through family connections,” she says. “My dad’s uncle knew my mum’s family from Sylhet. There was a meeting, a conversation, and a decision. It wasn’t romantic in the Western sense, but it was structured. Everyone knew their role.” She pauses. “The apps have no structure. Nobody knows their role. You’re just… out there.”

Fatima’s story is not unusual. It is, in many ways, the defining romantic experience of a generation: the South Asian diaspora, spread across London, Toronto, New York, Sydney, Dhaka, and a hundred cities in between, navigating a collision between two systems of love that the algorithms have not yet learned to reconcile.

From Biodata to Bumble: A Brief History

To understand where South Asian matchmaking is going, you need to understand where it came from.

For centuries, marriage across South Asia was arranged through kinship networks. Families exchanged biodata—one-page documents listing a prospective partner’s education, occupation, family background, height, complexion, and (in the most traditional versions) horoscope compatibility. The process was communal, structured, and explicitly transactional. Love, if it came at all, was expected to develop after the match, not before it.

The first disruption came in the 1990s with matrimonial websites. Shaadi.com, launched in 1997, digitized the biodata. BharatMatrimony followed. These platforms expanded the pool but preserved the logic: families searching for families, filtered by caste, religion, income, and education. The individual was still embedded in a network.

Then came the dating apps. Tinder arrived in India in 2014. Bumble followed. Hinge, Muzz, Dil Mil, and dozens of others entered the market. And for the first time in South Asian romantic history, the individual was unmoored from the family. You could search alone. Match alone. Meet alone. The community was no longer in the room.

For many young South Asians, this was liberation. For their parents, it was bewilderment. For the culture, it was a rupture that is still being negotiated.

| THE SOUTH ASIAN DATING LANDSCAPE IN 2026

• Shaadi.com: 35 million registered users. Still primarily family-driven. • Dil Mil: 3+ million users. Positioned as “for the South Asian diaspora.” • Muzz: 10+ million users globally. Muslim-focused with family involvement features. • Aisle: Indian app blending modern UX with traditional values. Requires verified profiles. • Bumble India: Fastest-growing market. The women-first model challenges gender dynamics. • Tinder: 7.8 million users in India alone—but widely considered “too Western” by many families. |

The Double Life: Dating in Secret, Marrying in Public

For many South Asian diaspora singles, the dating app is a secret kept from the very people whose opinion matters most.

| VOICES—BANGLADESHI DIASPORA, UK

Raihan Ahmed, 32, Software Engineer, Birmingham “I’ve been on Muzz and Hinge for two years. My parents don’t know. If I told my mother I was looking for a wife on my phone, she would cry. Not because she thinks it’s wrong, exactly, but because she would feel like she’d failed. Like I didn’t trust her to find someone.” “The thing is, I do trust her. But her network is limited to Sylheti families in Birmingham and East London. That’s maybe a few hundred eligible women. The app gives me thousands. The math is just… better.” “But I can’t tell her that. So I swipe in private and hope that whoever I find will be someone I can introduce as a “family connection’ later. It’s a strange way to start a marriage—with a lie about how you met.” |

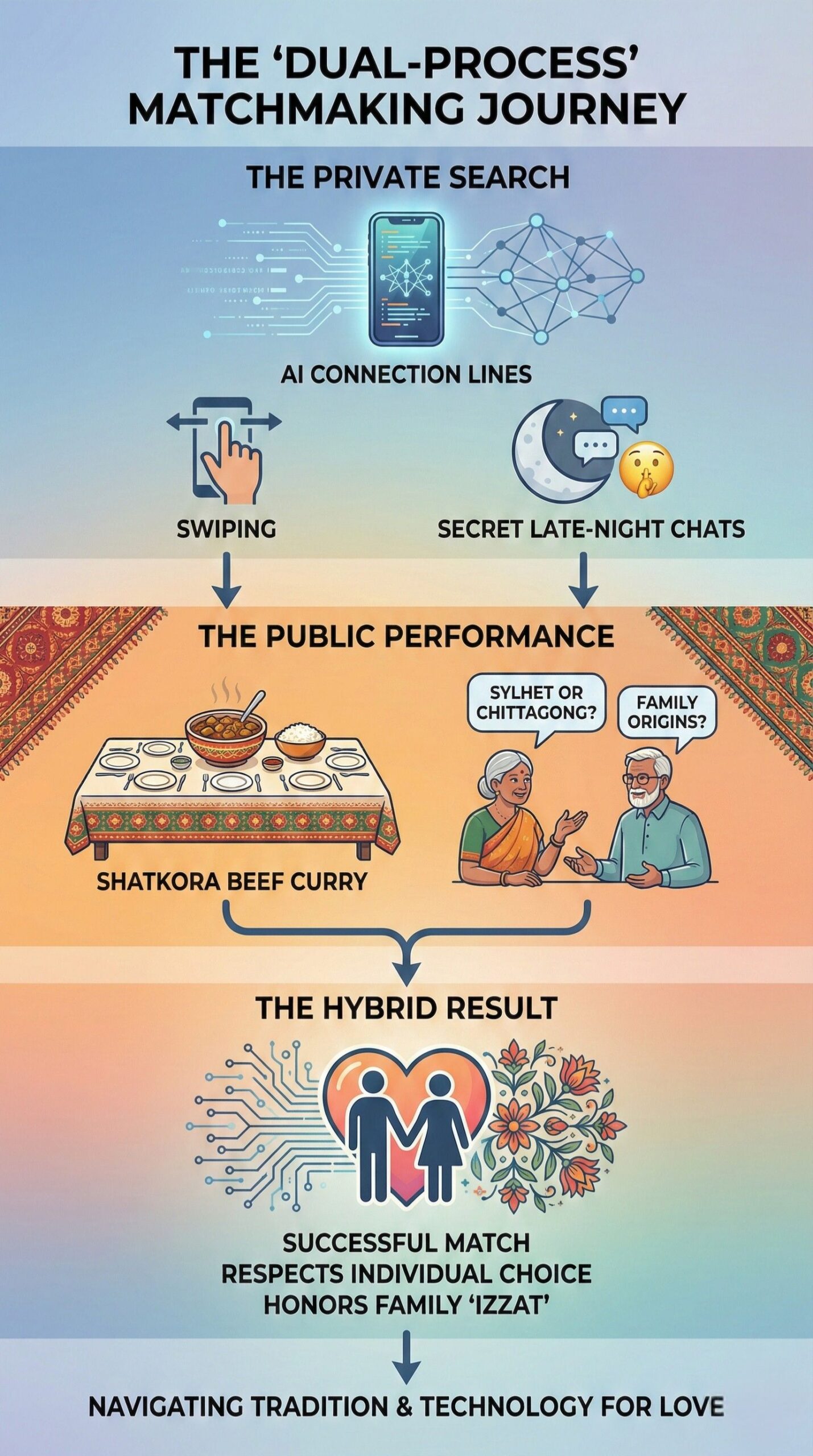

Raihan’s experience—the parallel track of private digital search and public family performance—is remarkably common. Researchers call it “dual-process matchmaking”: the practice of using apps privately while simultaneously participating in family-mediated introductions, with the understanding that whichever path produces a viable match first will be presented as the “official” origin story.

The secrecy is not about shame. It is about respect for a system that is still emotionally powerful even when it is practically insufficient. The diaspora family does not reject arranged marriage because it is old-fashioned. It holds onto it because it represents something the algorithm cannot: the participation of a community in one of life’s most important decisions.

| EXPERT INSIGHT

“In South Asian cultures, marriage is not a contract between two individuals. It is an alliance between two families. When young people use dating apps independently, they are not just choosing a partner—they are choosing to exclude their family from the process. That exclusion carries emotional weight that Western frameworks of individual autonomy often fail to appreciate.” — Dr. Rochona Majumdar, Professor of South Asian Studies, University of Chicago |

The Bangladeshi Lens: Dhaka, Diaspora, and the Digital Rishta

The Bangladeshi experience of this collision has its own distinct texture. Bangladesh’s matchmaking traditions are deeply rooted in extended family networks, regional identity (particularly the distinction between Sylheti, Chittagonian, and Dhaka-centric families), and a concept of family honor—izzat—that makes the stakes of romantic choice feel higher than personal preference alone.

In Dhaka, dating apps are growing rapidly among urban, educated young professionals—but largely in silence. The apps exist in a cultural grey zone: widely used, rarely discussed, and almost never acknowledged in family settings. A young woman in Dhanmondi might spend her evenings on Bumble, but her parents are simultaneously circulating her biodata among relatives in Comilla or across the diaspora in London and New York.

| VOICES—BANGLADESH

Nusrat Jahan, 26, Marketing Manager, Dhaka “In Dhaka, if your parents find out you’re on a dating app, the reaction depends entirely on your family. Some families would be understanding. Mine would not be. My father would see it as a failure of his responsibility. My mother would worry about what the relatives would say.” “So I use Bumble, but I use a photo that doesn’t show my face clearly. I don’t connect it to my Instagram. I never swipe on anyone who might know my family. It’s dating, but it’s also espionage.” “The absurd part is that I’m not doing anything wrong. I just want to meet someone on my own terms. But ‘my own terms’ is not a concept my family’s matchmaking system has a category for.” |

For Bangladeshi women in particular, the stakes are compounded by gendered expectations. A man using a dating app is quietly tolerated; a woman doing the same risks a different kind of social scrutiny. The double standard mirrors broader gender dynamics in Bangladeshi society, but the apps have made it more visible—and more contested.

In the diaspora, the dynamic shifts but does not disappear. British-Bangladeshis in Tower Hamlets, Bangladeshi-Canadians in Toronto’s Danforth corridor, and Bangladeshi-Americans in Jackson Heights, Queens, all navigate a version of the same tension: the pull of individual choice against the gravity of communal expectation. The geography changes. The emotional architecture rarely does.

| VOICES—BANGLADESHI DIASPORA, CANADA

Sadia Rahman, 30, Dentist, Toronto “My family left Chittagong when I was four. I grew up in Scarborough. I’m Canadian in every functional way. But when it comes to marriage, I’m suddenly Bangladeshi again.” “My parents want a Bangladeshi Muslim man, preferably from a Chittagonian family, ideally a doctor or engineer. The apps don’t have a filter for ‘will your mother approve of his family’s village of origin.’ And honestly, that’s the filter that matters most.” “I love my parents. I respect the tradition. But I’m also a 30-year-old woman with a career and opinions. Somewhere between the biodata and the Bumble profile, there has to be a version of this that works for all of us. I just haven’t found it yet.” |

Some platforms are beginning to adapt. Muzz allows users to add a “wali”—a family guardian—as a chaperone to conversations. Aisle, an Indian app, requires detailed profile verification and encourages users to state family involvement preferences upfront. Shaadi.com has introduced AI-driven match suggestions that factor in family compatibility metrics alongside individual preferences.

But the bigger challenge is one that AI has yet to solve: how to create an algorithm that can tell the difference between what a person wants and what their family expects. What is the difference between what a person swipes on privately and what they would bring home publicly? Between the version of themselves they have on the app and the version they need at the dinner table?

These are not technical problems. They are cultural ones. And culture, for all its patterns, resists the clean logic of machine learning.

The Conversation That Hasn’t Happened

At the heart of the South Asian diaspora’s matchmaking crisis is a conversation that most families have not yet had: an honest reckoning between the generation that believes marriage should be a family decision and the generation that believes it should be a personal one.

The older generation is not wrong. Arranged marriages, when conducted with genuine care, provide a support structure that purely individual choices often lack. Families that participate in the selection process tend to be more invested in the marriage’s success. Divorce rates in arranged marriages are statistically lower—though researchers caution that this may reflect social pressure to stay rather than genuine marital satisfaction.

The younger generation is not wrong either. Individual choice, emotional compatibility, and the freedom to discover a partner through personal experience are not Western impositions. They are human aspirations that transcend cultural boundaries. A marriage that begins with genuine attraction and shared values is valid even if it started on an app instead of at a family gathering.

| VOICES—INDIAN DIASPORA, USA

Arjun Mehta, 35, Physician, New Jersey “I married a woman I met on Dil Mil. My parents were… complicated about it. They liked her. She’s Gujarati, Hindu, and well-educated—everything they would have picked. But the fact that I picked her, without asking them first, was the wound. Not who she was. How I found her.” “We’ve been married three years now. My parents adore her. But my mother still occasionally says, ‘I could have found you someone just as good.’ And I think what she’s really saying is, ‘I wanted to be part of this. And you didn’t let me.’ |

Arjun’s mother’s grief is real, and it is shared by millions of South Asian parents who feel—correctly—that they are being displaced from a role they consider sacred. The matchmaking auntie, the family WhatsApp group circulating biodata, the intercontinental phone calls comparing prospects—these are not just processes. They are expressions of love, of investment, of a community’s participation in its continuation.

When an algorithm replaces that process, it is not just efficient. It is lonely for the older generation.

Towards a Hybrid Model: What Might Actually Work

The future of South Asian matchmaking is unlikely to be purely algorithmic or purely traditional. It will, in all probability, be hybrid—a model that blends the individual agency of digital platforms with the communal wisdom of family involvement. The question is how to build that hybrid without destroying what is valuable in either system.

Family-Integrated Features

Apps that allow family members to participate—not as gatekeepers, but as advisors—may bridge the gap. Muzz’s wali feature is an early experiment. A more developed version might allow parents to create a parallel profile with family preferences, which the algorithm incorporates alongside individual ones. The young person retains the final choice. The family retains involvement. Neither is excluded.

Culturally Trained Algorithms

AI matchmaking models trained on Western dating data will inevitably produce Western-biased results. Platforms serving South Asian communities need training data that reflects the actual decision-making criteria of those communities—including family background, regional identity, and religious practice. This is not a technical impossibility. It is a business priority that most platforms have not yet adopted.

The Honest Conversation

No technology can substitute for the conversation that most diaspora families need to have: an honest, respectful dialogue about what each generation values, what they fear, and what they are willing to compromise. Parents must comprehend that apps do not signify a rejection of their love. Children who understand that family involvement is not a denial of their autonomy. A shared recognition that the goal—a happy, lasting partnership—is the same, even if the paths diverge.

That conversation is harder than building an algorithm. It is also more important.

Final Words

The evolution of South Asian matchmaking is unlikely to end in a victory for one system over the other. Instead, the path forward lies in a hybrid model—a “messy, beautiful” fusion where digital agency meets communal wisdom.

While AI can efficiently analyze swipe patterns and interests, it currently lacks the capacity to navigate the unspoken nuances of regional origin, religious denomination, and the emotional weight of family approval. As Dr. Sheena Iyengar notes, the apps that will ultimately succeed are those that recognize the “user” is not just the person holding the phone but the entire family standing behind them.

Ultimately, technology cannot substitute for the honest conversation that needs to happen across the dinner table.

-

For parents: It is a journey toward understanding that dating apps are not a rejection of family love.

-

For children: It is an acknowledgment that family involvement is not necessarily a denial of autonomy.

As Fatima Chowdhury discovered, the apps might teach a person what they are looking for, but the final connection often remains a deeply human one. Whether a match begins with a biodata or a Bumble profile, the goal remains a partnership that honors both the individual’s heart and the community’s heritage.

Note: Some names in this article have been changed at the request of participants. Interviews were conducted between November 2025 and January 2026 across London, Dhaka, Toronto, and New York.