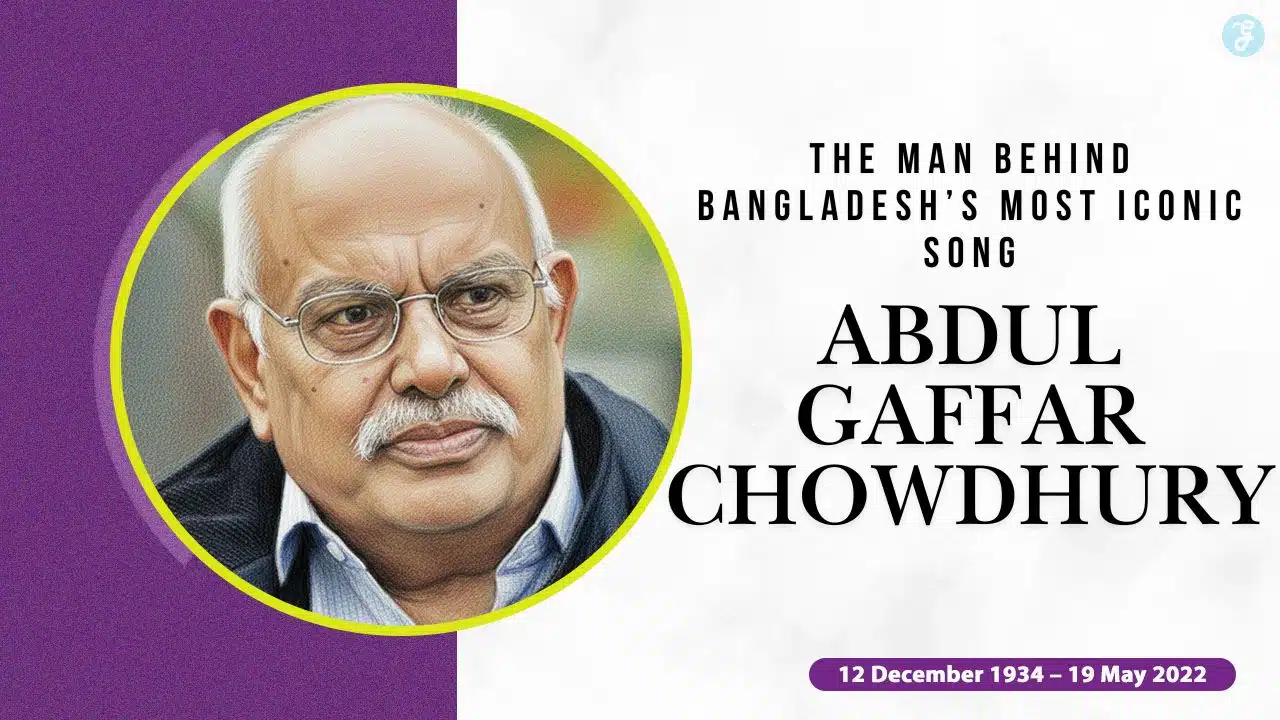

Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury is one of the rare figures whose words transcended literature and became the beating heart of a nation. To millions of Bangladeshis across the globe, he is not just a writer, journalist, or activist—he is the voice that crystallized the grief and defiance of the Language Movement into a single immortal anthem.

Born on 12 December 1934 in Ulania, Mehendiganj of Barisal, and passing away on 19 May 2022 in London, Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury’s life spanned British India, Pakistan, and independent Bangladesh. He was not only a lyricist of a legendary song, but also a journalist, columnist, political analyst, and a witness to some of the most turbulent chapters in Bengali history.

His song, Amar Bhaier Rokte Rangano Ekushey February, turned sorrow into strength, memory into monument, and resistance into national identity. But behind this towering cultural legacy lies a life rich with political struggle, intellectual courage, journalistic brilliance, and unwavering devotion to Bangladesh’s history and humanity.

As we celebrate his birthday, we revisit the full story of the man whose pen shaped a movement, preserved a nation’s language, and left behind one of the most powerful literary legacies in South Asian history.

Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury at a Glance

Before diving into his life story, it helps to see the broad outline of who he was and what he did.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Abdul Gaffar Choudhury |

| Birth | 12 December 1934, Ulania, Mehendiganj, Barisal, British India |

| Death | 19 May 2022, London, United Kingdom |

| Professions | Writer, journalist, columnist, political analyst, poet |

| Signature Work | Lyricist of “Amar Bhaiyer Rokte Rangano” |

| Movements Linked To | Bengali Language Movement, Liberation War era politics (as commentator) |

| Major Awards | Bangla Academy Award (1967), Ekushey Padak (1983), Independence Award (2009) |

| Later Life Base | London, from 1974 onward |

Even this small snapshot shows why he matters. He stands at the crossroads of language, politics, culture, and memory.

Childhood Environment and Cultural Roots in Barisal

Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury was born into a culturally vibrant and politically aware community in Ulania, Barisal. The region was known for its poets, teachers, intellectuals, and reformers, providing a fertile backdrop for a budding writer. Growing up surrounded by riverine beauty, folk rhythms, and social struggles deeply shaped his emotional and artistic instincts. His father, Hazi Wahed Reza, was a respected figure and freedom fighter, giving young Gaffar both literary grounding and political consciousness from an early age.

This early blend of nature, music, and activism would later echo powerfully in his poems, political commentary, and especially in the emotional weight of Amar Bhaier Rokte Rangano.

Roots in a Political and Cultural Household

Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury did not appear out of nowhere. He grew up in a family where politics and public life were part of everyday conversation. His father, Haji Wahed Reza Chowdhury, was a landlord and an active freedom fighter who joined the anti-colonial struggle and took part in the Indian National Congress.

Growing up in Barisal, young Gaffar was surrounded by:

-

Stories of resistance to British rule

-

Debates on independence, democracy, and rights

-

A culture where literature and politics flowed together

This environment shaped him in three important ways:

-

It gave him a deep sense of political consciousness from an early age.

-

It taught him that words, speeches, and songs could move people to action.

-

It made him feel responsible for his language and his land.

By the time he moved to Dhaka for studies, he was not just a student but a keen observer of history in the making.

Political Awakening and Early Activism

From his school years, Gaffar Chowdhury showed an unusual sensitivity to injustice and identity politics. The social tensions simmering in East Bengal, the growing inequality between East and West Pakistan, and the rising call for linguistic rights shaped his political awareness.

As a student, he became involved in discussions, rallies, and underground meetings centered around cultural protection. This early exposure to political struggle laid the foundation for his sharp journalistic instincts and bold activism in the decades to come.

From Language Movement Witness to Its Lyricist

When the Language Movement gathered force in the early 1950s, Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury was a young man in Dhaka. The idea that Bangla should be recognised as a state language was not an abstract question for him. It was about dignity, identity, and survival.

He was present in that environment of tension and hope, as students organised marches and the state responded with growing hostility. On 21 February 1952, police firing on protesters changed everything. The martyrs of Ekushey turned the movement into a permanent scar on the nation’s memory.

The Making of the Ekushey Anthem: Origins, Emotions, and Circumstances

The story behind Amar Bhaier Rokte Rangano Ekushey February is as moving as the song itself. Chowdhury wrote the poem shortly after the tragic events of February 21, 1952, when police opened fire on students demanding recognition for Bangla as a state language. Grief, anger, and determination flowed through him as he transformed the collective pain of a people into lines that were instantly embraced as the anthem of resistance.

The song became more than poetry—it became history’s witness. It captured the essence of sacrifice and turned Ekushey into a symbol of linguistic pride. Even decades later, the song is sung every year with the same intensity, proving how deeply his words are woven into national identity.

The Birth of “Amar Bhaiyer Rokte Rangano”

In the middle of this trauma, Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury wrote lines that would echo for generations:

“Amar bhaiyer rokter angano Ekushey February

Ami ki bhulite pari.”

He wrote the lyrics in 1952, capturing the grief and defiance of the moment. The song later gained its now-famous tune, composed by Altaf Mahmud, and slowly became the central musical expression of the Language Movement.

The song worked on several levels:

-

It was a mourning song for the brothers who had died.

-

It was a protest song, refusing to forget what the state wanted erased.

-

It was a promise that the sacrifice of the martyrs would not be wasted.

How the Song Became an Anthem

“Amar Bhaiyer Rokte Rangano” did not become iconic overnight. It grew with:

-

Each 21 February commemoration, as mourners and activists sang it at the Shaheed Minar.

-

The spread of radio, cassettes, and later television carried the song into every home.

-

The recognition of Ekushey February by UNESCO as International Mother Language Day in 1999, which took the song to a global audience.

Over time, the song turned into:

-

A symbol of linguistic rights around the world

-

A shorthand for the entire story of 1952

-

A piece of living heritage that every Bangladeshi child eventually learns

Pro Tip: If you want to understand Bangladesh beyond textbooks, start by listening to “Amar Bhaiyer Rokte Rangano” with a translation of the lyrics. It tells you as much as any history chapter.

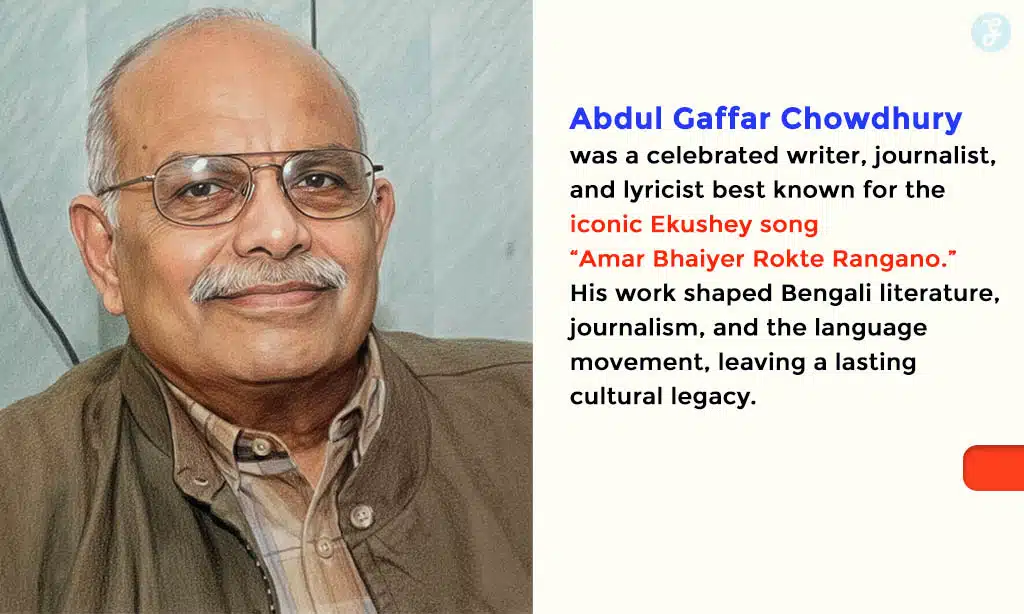

Beyond One Song: A Prolific Writer and Journalist

While it is tempting to reduce Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury to a single song, that would be unfair. He wrote columns, essays, short stories, and political analysis over several decades.

After 1974, he settled in London, where he continued to write regularly for Bangladeshi newspapers and media. His columns often engaged with:

-

The political direction of Bangladesh

-

Democracy, military rule, and the dangers of authoritarianism

-

Corruption, inequality, and human rights

-

The experience of the Bangladeshi diaspora in the United Kingdom

His writing style was marked by:

-

Clear, direct language

-

Strong moral positioning

-

A mix of historical memory and current affairs

In many ways, he acted as a long-distance conscience for the country, even while living abroad.

A Voice of Conscience for Bangladesh

From London, Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury watched Bangladesh’s journey through independence, coups, military regimes, democratic experiments, and ongoing political conflict. He was never shy about speaking his mind.

Through his columns and speeches, he:

-

Warned against forgetting the ideals of the Liberation War

-

Criticised those who tried to rewrite history or downplay the Language Movement

-

Defended secular, pluralistic values against extremism

-

Highlighted the struggles of ordinary Bangladeshis, both at home and in the diaspora

He often took positions that were unpopular with some groups, but he stayed consistent in his belief that the sacrifices of 1952 and 1971 should guide the nation’s moral compass.

Style, Themes, and Literary Identity

Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury’s work crosses genres, but several threads unite it.

Key themes in his writing and commentary:

-

Language and identity

-

Justice and state violence

-

Memory, especially around 1952 and 1971

-

Responsibility of intellectuals and writers

-

Love for Bangla as both language and cultural space

His style was not overly experimental or abstract. Instead, it was:

-

Accessible to ordinary readers

-

Rooted in lived experience

-

Driven by narrative and moral clarity

That balance is one reason why his work resonated across class and geography.

Awards, Honors, and National Recognition

Over his lifetime, Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury received some of the highest cultural and state honors available in Bangladesh.

| Award or Honor | Year | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Bangla Academy Literary Award | 1967 | Recognition of his contribution to Bangla literature |

| Ekushey Padak | 1983 | One of the highest civilian awards for culture and language |

| Independence Award (Swadhinata Padak) | 2009 | Highest civilian honor in Bangladesh |

| Various diaspora and media awards | Various | Appreciation from expatriate communities and media |

These awards underline two facts:

-

The state officially recognised his cultural and political importance.

-

His contributions remained relevant over many decades, not just one moment in 1952.

Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury and the Diaspora Experience

When he left Bangladesh and settled in London, Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury became part of a large community of Bangladeshi migrants in the United Kingdom.

For many in the diaspora, he represented:

-

A link back to the Language Movement and Liberation War

-

A respected elder whose columns explained politics at home

-

A cultural figure who reminded them where they came from

He gave speeches, joined events, and remained visible in the community. This kept the stories of 1952 and 1971 alive among younger generations born abroad.

His Contribution to Bangla Literature Beyond Political Writing

Although widely known for political commentary, Gaffar Chowdhury had a rich literary side. He wrote novels, short stories, essays, and satire that explored human relationships, social justice, and the psychological impact of political turmoil. His fiction often blended realism with emotional depth, reflecting the lives of ordinary people caught in extraordinary times.

His literary contributions broadened his legacy far beyond journalism, proving that he was not just a political mind but a storyteller of remarkable sensitivity.

Even after his death, Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury continues to live through:

-

School programs, cultural events, and television specials featuring his song and story

-

Reprints of his columns, memoirs, and essays

-

Documentaries and discussions about the Language Movement and Bangladeshi identity

In a digital era, his words travel further than ever before. Young people discover “Amar Bhaiyer Rokte Rangano” on streaming platforms and social media, sometimes before they fully know the history behind it.

Pro Tip: Teachers and parents can use his life as an entry point to teach children about language rights, cultural pride, and peaceful resistance. Turning one man’s story into a shared lesson is a powerful way to keep his legacy active.

Why Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury Still Matters

Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury is not just a figure from the past. His life and work continue to matter because they speak directly to issues that are still alive today.

He matters because:

-

He reminds us that language is worth fighting for.

-

He shows how a single song or text can capture an entire people’s pain and hope.

-

He proves that writers and journalists are not neutral observers; they can take sides in the struggle for justice.

-

He represents a bridge between generations, from the early Language Movement activists to the digital native youth of today.

In a time when misinformation spreads easily and history is often simplified or distorted, voices like his provide grounding and context.

Final Thoughts on Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury

A birthday tribute is not just about counting years. It is about pausing to ask what a life has meant, and what it continues to mean.

Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury was many things:

-

A son of Barisal who grew up in a politically charged household

-

A witness to the Language Movement who turned his grief into an anthem

-

A journalist and columnist who held up a moral mirror to Bangladesh from afar

-

A cultural icon whose words became part of the country’s emotional DNA

He will always be remembered as the man behind Bangladesh’s most iconic song. But he was also much more than that. He was a reminder that pen and paper, or today a keyboard, can still stand up to guns and power.

As each new February and each new December come and go, his song will continue to be sung, his story will continue to be told, and his legacy will continue to shape how Bangladesh understands itself.

In that sense, Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury is not only part of history. He is part of the living present of every Bangladeshi who believes that language, justice, and memory matter.