On February 12, 2026, Bangladesh did not merely hold an election—it conducted a national reckoning. Fifty-five years after winning independence from Pakistan at the cost of three million lives, the nation faced a stark choice: embrace the forces that once opposed its very existence, or recommit to the democratic, secular, and economically progressive vision for which the liberation war was fought. The verdict was unequivocal.

Jamaat-e-Islami, the Islamist party whose leadership collaborated with Pakistani occupation forces in 1971, whose militias participated in mass atrocities, and whose ideological descendants have spent decades seeking to rehabilitate their tarnished legacy, suffered a crushing defeat. Despite fielding an aggressive 11-party coalition, deploying extensive grassroots networks, and banking on the political vacuum left by the Awami League’s suspension, Jamaat secured only 77 seats.

Meanwhile, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party swept to a commanding 212-seat victory, achieving a two-thirds supermajority on a platform that married economic pragmatism with unwavering commitment to the ideals of 1971.

This was not simply a political defeat for Jamaat. It was the definitive rejection of anti-liberation forces by the very generation that inherited the fruits of independence. The youth who overthrew Sheikh Hasina’s autocracy in July 2024, who risked their lives for democratic renewal, looked at Jamaat’s theocratic vision and saw not salvation but betrayal—betrayal of the secular, democratic Bangladesh their grandparents died to create.

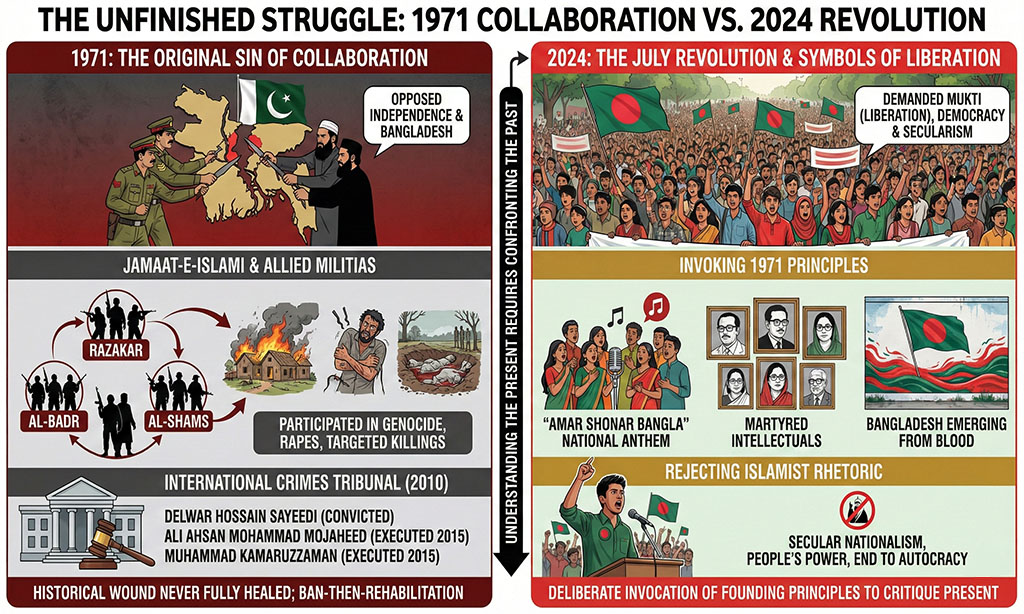

1971: The Original Sin of Collaboration

To understand the significance of Jamaat’s 2026 defeat, we must first confront the historical wound that has never fully healed. When Bengali nationalists declared independence from Pakistan in March 1971, Jamaat-e-Islami stood firmly with the occupation forces. The party’s leadership openly opposed the creation of Bangladesh, viewing it as a conspiracy to divide the Muslim ummah and weaken Pakistan.

But Jamaat’s role transcended mere political opposition. The party’s student wing and allied militias formed the backbone of the Razakar, Al-Badr, and Al-Shams paramilitary groups that actively collaborated with the Pakistani military in identifying, capturing, torturing, and executing Bengali intellectuals, students, and independence supporters. These collaborators participated in some of the worst atrocities of the genocide—mass rapes, systematic killings of Hindu minorities, and the targeted assassination of Bangladesh’s brightest minds just days before the Pakistani surrender.

The International Crimes Tribunal, established in 2010, documented these crimes in painstaking detail. Senior Jamaat leaders were convicted of crimes against humanity, including Delwar Hossain Sayeedi, Ali Ahsan Mohammad Mojaheed (executed in 2015), and Muhammad Kamaruzzaman (executed in 2015). The verdicts were based on witness testimony, documentary evidence, and the findings of international human rights organizations.

For decades after independence, this history haunted Bangladeshi politics. Jamaat was banned in 1972, then gradually rehabilitated as a political force during the military dictatorships of the late 1970s and 1980s. By the 1990s, the party had reinvented itself as a legitimate political actor, even serving in coalition governments. But the stain of 1971 never washed away. To millions of Bangladeshis, Jamaat remained the party of rajakars—traitors who sold their nation for religious ideology.

2024: The July Revolution and the Symbols of Liberation

When students took to the streets in July 2024 to protest discriminatory quota systems, they initially framed their demands in economic terms—fair access to government jobs, meritocratic hiring, an end to patronage. But as the Hasina government responded with bullets rather than dialogue, the movement rapidly transformed into something larger: a struggle for the soul of Bangladesh itself.

The symbolism protesters deployed was deliberate and powerful. They invoked mukti (liberation), the same rallying cry that animated 1971. They sang “Amar Shonar Bangla”, the national anthem written by Rabindranath Tagore that celebrates Bengali cultural identity. They carried portraits of martyred intellectuals killed by razakars in December 1971. They painted murals showing the red and green flag of Bangladesh emerging from the blood of the fallen.

This was not nostalgia. It was a deliberate invocation of 1971’s founding principles to critique the present. The message was clear: Bangladesh was founded as a secular, democratic nation where power derived from the people, not from military force or hereditary rule or religious authority. Hasina had betrayed those principles through autocratic governance. The youth demanded their restoration.

Critically, the July Revolution remained firmly within the tradition of 1971’s secular nationalism. When some opportunistic voices attempted to inject Islamist rhetoric into the protests, student leaders forcefully rejected it. They understood that the struggle for democracy and the struggle against religious authoritarianism were inseparable. Their grandparents had not fought for liberation only to hand power to the forces that opposed that liberation in the first place.

The 2026 Ballot: Economic Survival Meets Historical Justice

International observers expected Jamaat to capitalize on the post-Hasina vacuum. The party had built a formidable organizational infrastructure over decades—madrassas providing education and social services, charitable networks offering relief to the poor, mosque-based mobilization reaching into every village. With the Awami League suspended, analysts predicted Jamaat could sweep conservative rural constituencies and emerge as a kingmaker, if not the outright victor.

They were catastrophically wrong. When the votes were counted, Jamaat’s ceiling was 77 seats—a humiliating outcome for a party that had formed an 11-party alliance specifically to maximize its reach. The BNP, running largely on its own with limited coalition partners, secured 212 seats and a two-thirds supermajority.

What happened? The answer lies in understanding that Bangladesh’s electorate—especially its youth—made a calculation that was simultaneously pragmatic and principled. They rejected Jamaat not despite their economic anxieties, but because of them.

Consider the economic realities facing voters. GDP growth had collapsed to 3.9%, the lowest in decades. Youth unemployment stood at 11.46%, with 84% of the labor force trapped in the informal sector lacking job security or benefits. Inflation hovered at 8.5%, crushing household purchasing power and making basic staples like rice, lentils, and cooking oil increasingly unaffordable. The garment sector—backbone of Bangladesh’s export economy and employer of millions of women—faced disruption from factory closures and labor unrest.

For a 22-year-old graduate with a university degree but no job prospects, Jamaat’s pitch was fundamentally unserious. The party offered religious purity, moral restoration, and vague promises of Islamic welfare. What it did not offer was a credible plan to revive economic growth, attract foreign investment, integrate Bangladesh into global tech supply chains, or create the millions of jobs the country desperately needed.

Bangladesh’s Economic Crisis on the Eve of the 2026 Election

| Indicator | 2025 Crisis Level | Impact on Voters |

| GDP Growth | 3.9% (lowest in decades) | Economic stagnation, no job creation |

| Youth Unemployment | 11.46% | Educated youth with no prospects |

| Inflation (CPI) | 8.5% | Households cannot afford basics |

| Informal Sector | 84% of workforce | No job security, benefits, or protection |

| FDI Inflows | Severely reduced | Limited capital for growth and jobs |

The BNP, by contrast, ran a campaign that treated voters like rational economic actors rather than religious subjects. Their manifesto promised “Make in Bangladesh” tech hubs to absorb educated youth, international payment gateway integration to support the country’s massive freelance workforce, healthcare spending increases to 5% of GDP, and a “Family Card” system providing subsidized essential commodities to struggling households.

This was not merely economic policy; it was a vision of Bangladesh’s future that directly descended from 1971. The liberation war was fought for Bangladesh to control its own economic destiny, to build a modern state that served its people’s material needs, to integrate into the global economy as an independent actor rather than remaining a peripheral supplier of cheap labor. The BNP’s economic platform honored that legacy. Jamaat’s theocratic vision rejected it.

The Women’s Verdict: Rejecting Patriarchy, Defending Liberation

Perhaps no constituency delivered a more devastating verdict against Jamaat than Bangladesh’s women. This matters immensely, because women are not merely voters—they are the foundation of Bangladesh’s economic miracle. Over 4 million women work in the ready-made garment sector, generating 80% of the country’s export earnings. Millions more work in agriculture, small businesses, and service industries. Women’s labor force participation has been Bangladesh’s greatest development success story.

Jamaat’s platform threatened this achievement. During the campaign, party leaders made regressive statements about women’s roles, workplace modesty requirements, and the need to strengthen “traditional family structures.” The subtext was unmistakable: a Jamaat government would seek to limit women’s economic autonomy and social mobility in the name of religious propriety.

Women voters understood the stakes. They remembered that in 1971, Pakistan’s military and their collaborators specifically targeted women through systematic rape campaigns designed to destroy Bengali cultural identity and demoralize the independence movement. The Birangona (war heroines)—women who survived sexual violence during the liberation war—remain living symbols of both the brutality Bangladesh escaped and the resilience that built the nation.

For these women and their daughters and granddaughters, voting against Jamaat was not merely an economic decision. It was a defense of the liberties won in 1971—the right to work, to move freely, to participate in public life, to define their own futures. The idea that they would trade Hasina’s authoritarianism for Jamaat’s patriarchal theocracy was insulting. They voted for the BNP because the party promised economic opportunity without demanding they retreat into the shadows.

The Geopolitical Calculation: Liberation From All Forms of Domination

Bangladesh’s 1971 liberation was fundamentally about asserting independence—from Pakistani military rule, yes, but more broadly from any external power that would treat Bangladesh as a subordinate rather than a sovereign nation. This principle remains alive in Bangladeshi political consciousness.

A Jamaat-led government would have compromised that independence. The party’s ideological and financial ties to Middle Eastern donors, its historical sympathy for Pakistan, and its hostility to secular Western institutions would have isolated Bangladesh diplomatically and economically. Western buyers who source 85% of Bangladesh’s garment exports would have reconsidered their supply chains. India would have viewed a Jamaat government as a security threat, straining relations with Bangladesh’s most important neighbor. Foreign direct investment would have collapsed.

Voters understood this. They recognized that Bangladesh’s economic future depends on maintaining productive relationships with India, the West, China, and regional partners—balancing these relationships carefully to preserve sovereignty while accessing markets, capital, and technology. Jamaat’s ideological rigidity threatened to destroy this balance, leaving Bangladesh isolated and impoverished.

The BNP, by contrast, ran on a platform of pragmatic engagement. Tarique Rahman personally reached out to Indian leadership, reassuring them about border security and minority rights. He signaled openness to Western investment while maintaining Bangladesh’s traditional non-aligned foreign policy. Within hours of the election results, Prime Minister Modi called to congratulate Rahman, and the U.S. Secretary of State issued a supportive statement. Markets responded positively.

This was liberation politics adapted to the 21st century. Just as Bangladesh fought for independence from Pakistan in 1971, it now asserts independence from any ideological framework—whether Islamist or autocratic—that would subordinate national interests to external agendas or rigid dogma. The BNP’s foreign policy pragmatism honored the spirit of 1971’s independence struggle.

The July Charter: Institutionalizing 1971’s Democratic Promise

The concurrent referendum on the July National Charter represented the institutional dimension of 1971’s rebirth. With 60.26% of voters approving, Bangladesh endorsed a comprehensive package of constitutional reforms designed to prevent the concentration of power that enabled both Hasina’s autocracy and, potentially, future authoritarian threats from any ideological direction.

The charter’s key provisions—prime ministerial term limits, a bicameral legislature to check executive power, enhanced judicial independence, and strengthened protections for fundamental rights—directly address the democratic deficits that have plagued Bangladesh since independence. These reforms recognize that 1971’s promise of democratic governance was never fully realized. The liberation struggle overthrew foreign military rule, but it did not automatically create stable democratic institutions.

What makes the charter’s passage particularly significant is that voters approved it alongside rejecting Jamaat. This was a comprehensive affirmation: yes to democracy, no to theocracy; yes to institutional limits on power, no to unchecked religious authority; yes to the secular, pluralistic vision of 1971, no to the reactionary alternative offered by those who opposed liberation.

The BNP’s decision to campaign in support of the charter, even though it constrains their own future power, demonstrates political maturity. They recognized that the electorate demanded insurance against authoritarianism from any source. By embracing these limits, the BNP positioned themselves as the legitimate heirs to 1971’s democratic aspirations—while Jamaat, which equivocated on the charter, revealed their comfort with concentrated authority as long as it served religious ends.

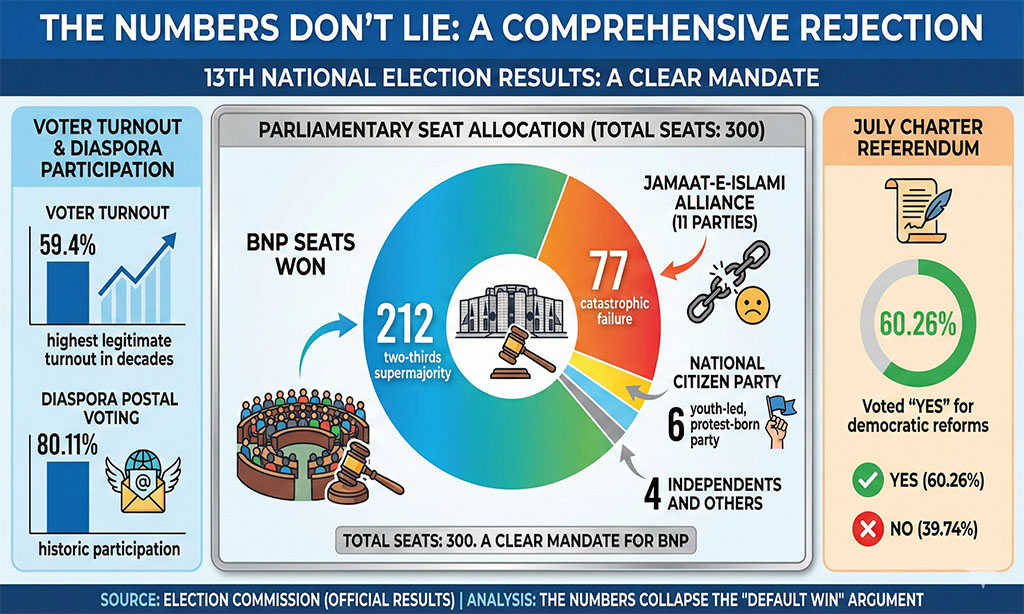

The Numbers Don’t Lie: A Comprehensive Rejection

Let us examine the electoral verdict in detail. Critics have attempted to dismiss the BNP’s victory as a “default win” resulting from the Awami League’s suspension. This argument collapses under scrutiny.

13th National Election Results: A Clear Mandate

| Category | Result |

| BNP Seats Won | 212 (two-thirds supermajority) |

| Jamaat-e-Islami Alliance (11 parties) | 77 seats (catastrophic failure) |

| National Citizen Party | 6 seats (youth-led, protest-born party) |

| Independents and Others | 4 seats |

| Voter Turnout | 59.4% (highest legitimate turnout in decades) |

| Diaspora Postal Voting | 80.11% participation (historic) |

| July Charter Referendum | 60.26% voted “Yes” for democratic reforms |

If this were merely a protest vote against the Awami League, Jamaat would have performed far better. They fielded candidates in nearly every constituency, deployed extensive resources, and had organizational capacity rivaling or exceeding the BNP. If voters simply wanted to punish the old regime without discriminating among alternatives, Jamaat should have won at least 120-150 seats in rural conservative areas where their social welfare networks are strongest.

Instead, they captured barely 25% of contested seats. This was not a default outcome. This was a deliberate rejection. Voters evaluated Jamaat’s platform—its economic proposals, its social policies, its historical legacy, its implications for Bangladesh’s future—and found it unacceptable. They chose the BNP not by accident but by design.

The near-60% turnout reinforces this interpretation. You don’t get historically high participation for a default vote. People showed up because they cared about the choice, because they understood what was at stake. They came to the polls to affirmatively endorse the principles of 1971 and reject the forces that opposed those principles.

The Road Ahead: Delivering on Liberation’s Promise

The BNP’s victory creates opportunity, not guarantees. Winning an election is the easy part. Governing effectively, implementing promised reforms, reviving the economy, and resisting the authoritarian temptations that have corrupted previous governments—these are far more difficult.

The youth who delivered this mandate are watching. They know how to organize mass protests. They know how to topple governments. They have already demonstrated zero tolerance for corruption and authoritarianism. If the BNP thinks their 212-seat majority gives them license to govern like the Awami League—concentrating power, enriching cronies, silencing critics—they will face the same fate as Hasina.

The first 100 days will be critical. The government must move aggressively on corruption prosecutions, demonstrating that accountability is real. They must fast-track the “Make in Bangladesh” tech initiatives to show young voters that job creation is the top priority. They must implement the July Charter reforms without delay, proving their commitment to institutional limits on power. And they must govern inclusively, protecting minority rights and respecting pluralism—core principles of 1971’s liberation struggle.

On the economic front, the challenges are immense. The BNP inherits 3.9% GDP growth, stalled foreign investment, and a labor force desperate for opportunities. They have promised to raise growth to 5.1-5.5%, reduce inflation to 6.5%, and create millions of jobs. These are ambitious targets that will require sound macroeconomic management, regulatory reforms to attract investment, and strategic investments in infrastructure and human capital.

The government must also navigate complex geopolitics. Maintaining productive relations with India while preserving sovereignty, engaging Western partners without compromising non-alignment, and balancing China’s economic influence with strategic autonomy—these require diplomatic skill and consistency.

Perhaps most importantly, the BNP must resist the temptation to marginalize Jamaat through extra-democratic means. Yes, Jamaat’s historical crimes demand justice. Yes, their theocratic ideology threatens Bangladesh’s secular foundations. But the appropriate response is not banning parties or suppressing speech. It is prosecuting war crimes through independent courts, countering extremist ideology through education and civil society, and out-competing Jamaat politically by delivering results that improve people’s lives.

This is the harder path, but it is the path of democratic maturity. Bangladesh’s 1971 liberation was not just about replacing one government with another. It was about establishing the principle that power derives from the people’s consent, exercised through free and fair elections, limited by constitutional checks, and subject to peaceful transfer when the people demand change. The BNP must honor those principles even when it is politically inconvenient.

Final Words: Liberation Continues

On February 12, 2026, Bangladesh completed a circle that began in March 1971. Fifty-five years after students and workers rose up against military dictatorship, students and workers rose again to reclaim their nation’s democratic soul. Fifty-five years after Bengali nationalism rejected subordination to Pakistani religious nationalism, voters rejected subordination to the Islamist ideology that opposed independence in the first place.

The defeat of Jamaat-e-Islami was comprehensive and definitive. Despite organizational advantages, despite the Awami League’s absence, despite eighteen months of political uncertainty that should have favored their grassroots networks, they secured only 77 seats. The forces that collaborated with Pakistan’s genocidal occupation, that murdered intellectuals and raped women to destroy Bengali identity, that spent decades seeking political rehabilitation—these forces were judged by Bangladesh’s youth and found wanting.

But this rejection was not merely punitive or backward-looking. It was forward-looking and constructive. Voters did not reject Jamaat only because of 1971; they rejected Jamaat because its 2026 platform offered nothing to address the economic crises facing ordinary Bangladeshis. They rejected theocracy not just on principle but because they recognized it would isolate Bangladesh economically, marginalize women who drive the economy, and betray the inclusive, progressive vision for which liberation was won.

The symbols of 1971 have been reborn because a new generation claimed them as weapons against both authoritarianism and theocracy. The red and green flag, the national anthem, the portraits of martyred intellectuals, the invocation of mukti—these are not museum pieces. They are living political tools that remind Bangladeshis what their nation stands for and what it refuses to become.

The challenge now is to ensure that this symbolic rebirth produces lasting institutional change. The July Charter provides a roadmap. The BNP’s mandate provides political capital. The youth’s mobilization capacity provides accountability. Whether these elements combine to create genuine democratic consolidation depends on choices made in the coming months and years.

But the electoral outcome itself is already historic. Bangladesh has demonstrated that liberation is not a single event that occurred in 1971 and was completed with independence. Liberation is an ongoing struggle—against foreign domination, against domestic authoritarianism, against religious extremism, against economic exploitation, against any force that treats the people as subjects rather than citizens.

The anti-liberation forces have fallen. The symbols of 1971 have been reborn. The work of actually building the Bangladesh those symbols promise—democratic, prosperous, just, and free—continues. This is the task the people have assigned to their new government. Whether that government succeeds or fails will determine not just Bangladesh’s immediate future, but whether the sacrifices of 1971 will finally be honored through the patient work of democratic governance.

The youth who voted on February 12, 2026 understand something profound: they are not merely inheriting their grandparents’ liberation, they are completing it. That work has only just begun.