Across cities from Los Angeles to Helsinki, tiny homes are popping up as a visible response to homelessness. What began as a small experiment is now becoming official policy in many parts of the world. In the United States, publicly funded tiny home villages are being built as transitional housing. In Los Angeles, the Department of Veterans Affairs plans to put up to 800 tiny homes on its West L.A. campus by 2026 to house veterans experiencing homelessness. Residents and housing advocates welcome the effort, but some wonder: is this meant as a bridge to permanent housing, or just a stopgap? In Seattle, nearly six million dollars has been set aside to build and run more than 100 tiny home shelters, many with on-site support services. Even smaller cities are joining the trend. Olympia, Washington, already has a tiny-home village, and Bellingham and Spokane are planning similar projects. Tiny homes are no longer on the margins of housing policy, they are steadily moving into the mainstream.

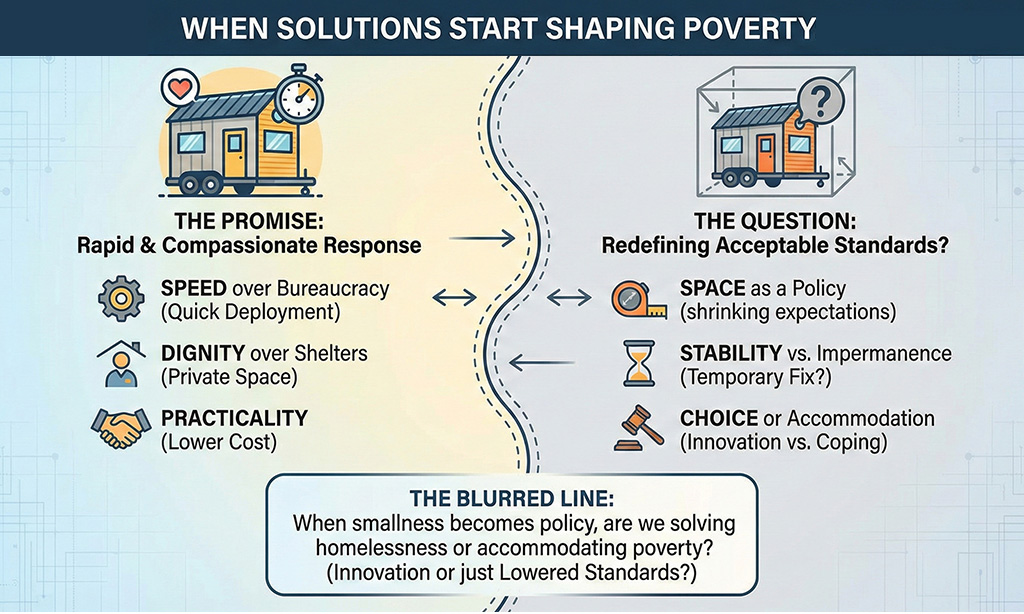

When Solutions Start Shaping Poverty

As housing crises get worse around the world, tiny homes are being promoted as fast, practical answers. Kind of compassionate solutions. They promise quick relief when bureaucracy slows things down and offer more dignity than overcrowded shelters. But there’s a bigger question: are tiny homes really solving homelessness, or are they quietly setting limits on how much space and stability the poorest can expect? When “small” becomes policy rather than a choice, the line between clever innovation and compromise starts to blur.

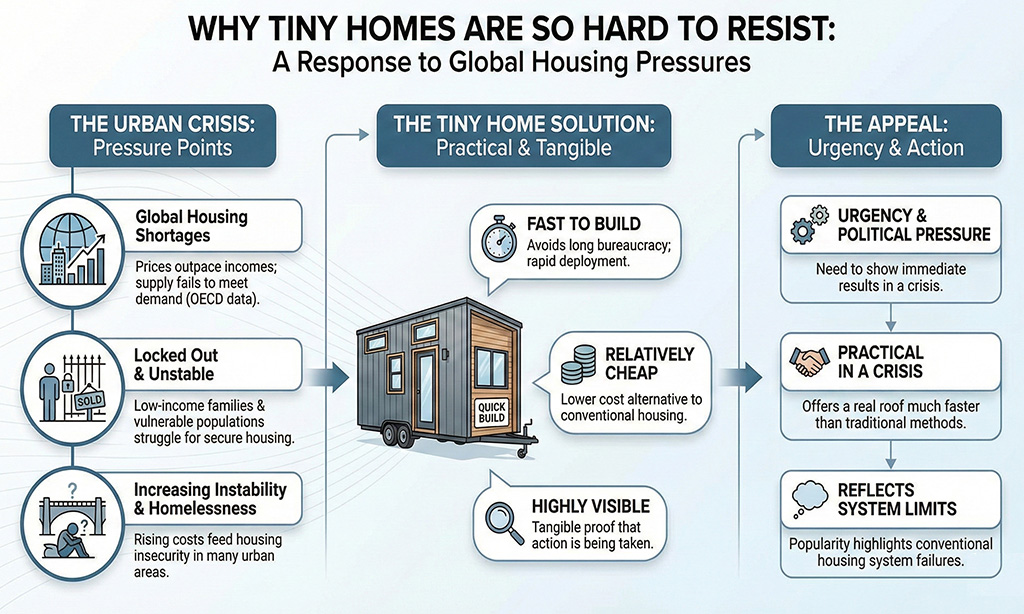

Why Tiny Homes Are So Hard to Resist

Tiny homes are catching on because cities everywhere are under pressure. Housing is expensive, and in many urban areas, prices have long outpaced what people earn. Families with low incomes often find themselves locked out of stable homes. Data from the OECD, the Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development shows that even in advanced economies, housing supply has not kept up with demand. Rising costs make safe, decent homes harder to find, pushing more people toward homelessness.

Tiny homes offer something traditional policies often cannot. They are fast to build, relatively cheap, and highly visible. A municipal housing official noted that tiny homes ‘added to the housing inventory quickly where other solutions were stalled by bureaucracy and zoning challenges.’ In other words, they give people a real roof, much faster than conventional approaches.

This mix of urgency, political pressure, and the need to show action helps explain their popularity. Tiny homes feel practical in a crisis. They are tangible proof that something is being done. But their appeal also reflects the limits of current housing systems as much as the creativity of those trying to solve homelessness.

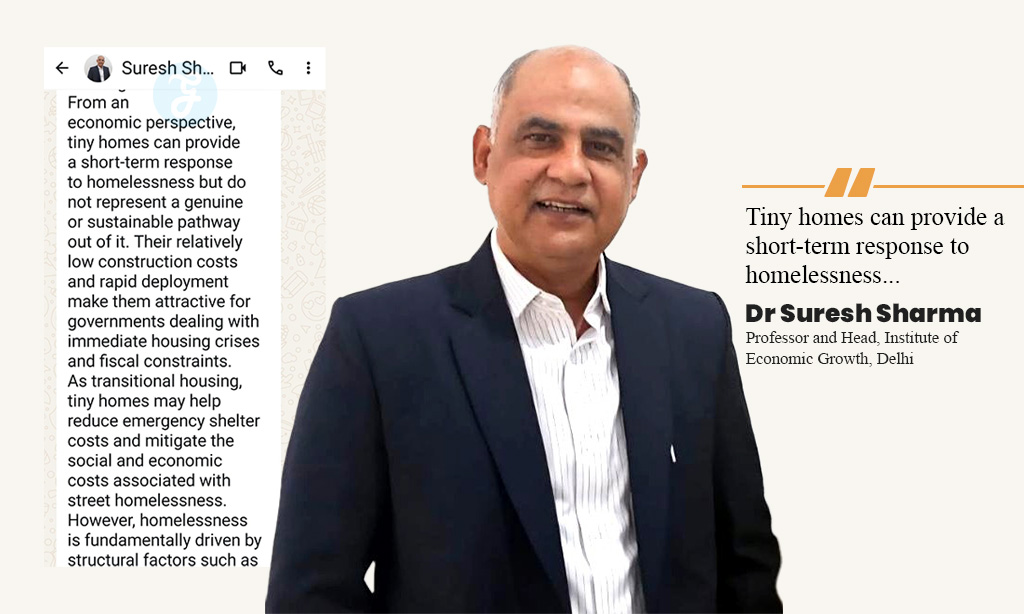

Economic Perspective on Tiny Homes

Dr Suresh Sharma, Professor and Head at the Institute of Economic Growth, Delhi, says: “From an economic perspective, tiny homes can provide a short-term response to homelessness, offering immediate shelter and reducing reliance on overcrowded shelters. Their low construction costs and rapid deployment make them attractive for governments in the United States and elsewhere facing urgent housing crises. However, these dwellings do not tackle the deeper structural issues driving homelessness, such as shortages of affordable housing, rising rents, and income insecurity. There is a risk that policymakers may treat tiny homes as a low-cost substitute for permanent solutions, gradually lowering expectations of what adequate housing should provide. Normalizing very small, temporary dwellings as long-term solutions can institutionalize a two-tier housing system and weaken the understanding of housing as a basic social right.”

Housing Is More Than a Roof: What Housing scholars say

As housing scholar Matthew Desmond puts it, “housing is absolutely essential to human flourishing” and without stable shelter everything else falls apart. His research shows that eviction and unstable housing are not just isolated issues. They feed into deeper cycles of poverty. Experts like Peter Marcuse and David Madden have also argued that housing policy often treats homes as market commodities instead of basic social rights, which can worsen inequality. This helps explain why even well-meaning programs sometimes fail to reduce homelessness over time. Across the globe, housing specialists agree: having a roof isn’t enough. Real housing needs security, permanence, and protection from forced displacement to truly support dignity and a stable life.

What Solutions Reveal About Priorities

Tiny homes often address visibility more than vulnerability. They give city leaders something tangible to point to, but they do not eliminate homelessness. They manage the problem rather than solve it. In doing so, they quietly lower expectations for the poorest. When governments celebrate how little space is “enough,” they reveal just how limited their ambition has become. This is what some critics call poverty with better branding: a solution that looks compassionate without changing the structures that create housing insecurity in the first place.

Residents see this clearly on the ground. One person living in a tiny-home village described it as safer than a shelter. At the same time, they admitted it did not feel permanent, equal, or something that could grow with their life. The walls keep out the cold, but not the sense that housing could be more than just survival.

Current systems, not small homes, are the problem

Even when well-intentioned, tiny homes reveal the limits of current housing systems. As Matthew Desmond has noted, “housing is absolutely essential to human flourishing” and without stable shelter everything else can fall apart. His research on eviction and instability shows that homelessness is not a personal failure but the result of deeper structural forces. Scholars Peter Marcuse and David Madden similarly argue that many housing policies reinforce inequality by treating homes as market commodities rather than social rights. In this light, tiny homes look less like a long-term solution and more like a way to manage poverty efficiently. They provide shelter, yes, but they do little to challenge the systems that leave families on the edge, quietly setting a ceiling on what the poorest can expect.

Life Inside a Tiny Home

Residents on the ground experience this tension firsthand. A person living in a tiny-home community in Canada described it as safer and more stable than traditional shelters. At the same time, they admitted it did not feel permanent or expandable, and that space was often too small to accommodate family or personal growth. “It keeps the cold out,” they said, “but it doesn’t give the sense that life can actually grow here.” Across the United States, similar experiences emerge. Says Thomas Smith (name changed on request), a resident of the tiny-home village in Olympia, Washington, “At least I can say I am not homeless.” He laughs on the phone as he says these words. His words underline a hard truth: tiny homes provide relief, but they do not fully restore the security, dignity, or long-term opportunity that truly adequate housing offers.

The Economic Paradox: Speed vs. Stability

This tension between efficiency and adequacy reveals what might be called the “Rapid Deployment Trap.” Dr. Suresh Sharma, of the Institute of Economic Growth, notes that the “low construction costs and rapid deployment” of tiny homes make them an irresistible “win” for city budget sheets and politicians facing public pressure. On paper, it is a success story of immediate relief. However, as Dr. Sharma warns, this efficiency risks “institutionalizing a two-tier housing system,” where the most vulnerable are moved into a secondary class of permanent “temporary-ness.”

We see this economic theory take a human shape in the lives of residents like Thomas Smith. When Thomas laughs on the phone and says, “At least I can say I am not homeless,” he is describing life within that second tier. He has secured the physical safety that Dr. Sharma acknowledges as a “short-term response,” but he remains trapped in a space that offers no path for the “growth” found in the first tier of traditional, permanent housing. By normalizing these micro-dwellings as a long-term fix, we risk redefining “success” not as the restoration of a person’s full social rights, but merely as the efficient management of their poverty.

Poverty with Better Branding

At the same time, the rise of tiny homes also illustrates what some critics call “poverty with better branding.” They look neat, modern, and intentional, and they allow cities to show action. Yet beneath the polished exterior, they often leave residents with limited space, uncertain futures, and few opportunities to move into truly adequate housing.

This tension raises the question in the headline: are tiny homes truly solving homelessness, or are they simply presenting poverty in a neater, more acceptable form?

Minimalism or Necessity

Tiny homes occupy a curious place in our collective imagination. For some, they are an aesthetic choice. Photos of minimalist interiors and clever storage make tiny living look chic and intentional. In wealthier circles, tiny homes have become symbols of simplicity and freedom, a way to reject consumer excess and focus on experiences rather than stuff. This idea of minimalism resonates with people who choose it as a lifestyle.

But for millions of people around the world, smallness is not a choice. It is a constraint. A tiny shelter is not a deliberate experiment in simplicity. It is a condition imposed by economic forces that narrow living options until only the smallest will fit. What looks like intentional living for one group becomes enforced scarcity for another. A tiny house that appeals on Instagram because it invites decluttering looks very different when it is the only available roof for someone who cannot afford anything larger or more secure.

This contrast is not just aesthetic. It reveals how we think about housing itself. For affluent buyers, tiny homes can be temporary retreats or eco‑friendly weekend getaways. For people struggling with poverty, tiny homes can become their expectation rather than their choice. When society frames compact living as clever or innovative, it risks normalizing a level of housing that fails to meet broader human needs for space, privacy, and growth.

Shrinking Ambitions or Real Alternatives

The appeal of tiny homes also reflects deeper structural questions about housing policy. Are tiny homes a practical bridge to stable living, or are they becoming a destination in themselves. Do they delay investment in real, long‑lasting affordable housing? Are they expanding housing options, or quietly shrinking expectations for what decent housing should be. Critics note that while tiny homes are quick to build and cheap compared with conventional housing, they do not always address the root causes of homelessness. Some analyses suggest they are best understood as a gap‑filling measure in the absence of more comprehensive policy responses.

International standards on housing reinforce this point. Adequate housing, as recognized by global bodies, involves much more than simple shelter. It means security of tenure, legal protection, access to services such as water and sanitation, and the ability for a household to live in dignity and safety. The current housing crisis is vast: United Nations estimates suggest that nearly three billion people worldwide lack access to adequate housing, and hundreds of millions are homeless or living in conditions that fail to uphold basic human rights.

Housing justice scholars and advocates argue that policy responses need to reflect these broader criteria. If housing is to be a foundation for opportunity and stability, it must meet standards of adequacy that go beyond simply providing a roof. When tiny homes are deployed in lieu of substantial investment in such housing, they can signal that society is settling for less.

Why Storytelling Matters

On the ground, this shift plays out in real life. Residents of tiny home communities often appreciate the safety and privacy these units offer compared with street homelessness. But they also speak of limitations: rooms that feel too small for daily life, a lack of permanence, and the sense that their future remains uncertain. These personal accounts underscore that shelter alone does not equal stability. Real housing is something people grow into over time, not something to which they are reduced.

This idea goes beyond policy and economics. It is about how we value human dignity and what we consider an acceptable life for the most vulnerable among us. When tiny homes become the best we can imagine for millions, the crisis is no longer just about housing alone. It becomes a quiet global acceptance of less than what human beings deserve.

Tiny homes may be necessary in moments of crisis and they may provide a useful tool in the broader toolkit of responses. But they must not become a permanent stand‑in for comprehensive solutions. If they do, we risk losing sight of the larger goal: a world where every person has access to secure, adequate, and dignified housing that allows them not just to survive, but to live fully.

Final Thoughts: Shelter, Safety, and the Limits of Small Solutions

Looking at tiny homes through the eyes of people like Thomas Smith in Olympia, Washington, it is easy to see why these communities are appealing. “At least I can say I am not homeless,” he says. That simple statement carries immense weight. For someone who has spent nights on the street or in overcrowded shelters, having a door to lock, a small space to call their own, and a sense of personal safety is a profound relief. Tiny homes offer speed, visibility, and immediate shelter, things traditional housing systems often struggle to deliver. They are inexpensive to build, can be deployed quickly, and give residents a real roof where once there was none. For city officials under pressure to show results, these projects provide tangible action.

At the same time, it is clear that tiny homes are not a full solution. They rarely offer permanence, and the spaces are often too small and inflexible for families or for residents to grow into. Around the world, residents echo this tension. They provide a roof, yes, but they cannot replace the long-term stability, security, and dignity that comes with truly adequate housing. In framing tiny homes as a sufficient answer, there is a risk of lowering expectations and accepting scarcity as normal for those who already have little. What feels like innovation for some becomes a quiet compromise for others.

In my view, tiny homes occupy a middle ground. They are neither a perfect solution nor a failure. They are a stopgap, a bridge in moments of urgent need, and a reminder that housing crises are complex and persistent. Thomas Smith’s words capture the essential truth: tiny homes matter because they provide immediate protection, safety, and dignity, but they are not enough to address structural inequities in housing.

Ultimately, tiny homes challenge us to think about what we value in society and how much we are willing to invest in ensuring that everyone has space, security, and the chance to live fully.