IMF’s 3.1% 2026 global growth forecast signals resilience after the inflation-and-rates shock, but it also reveals a world stuck in low gear. With tariffs, debt, and geopolitics rising, the number matters because it is the baseline for budgets, rate cuts, and risk-taking.

Why 3.1% Feels Both Better And Worse Than It Looks

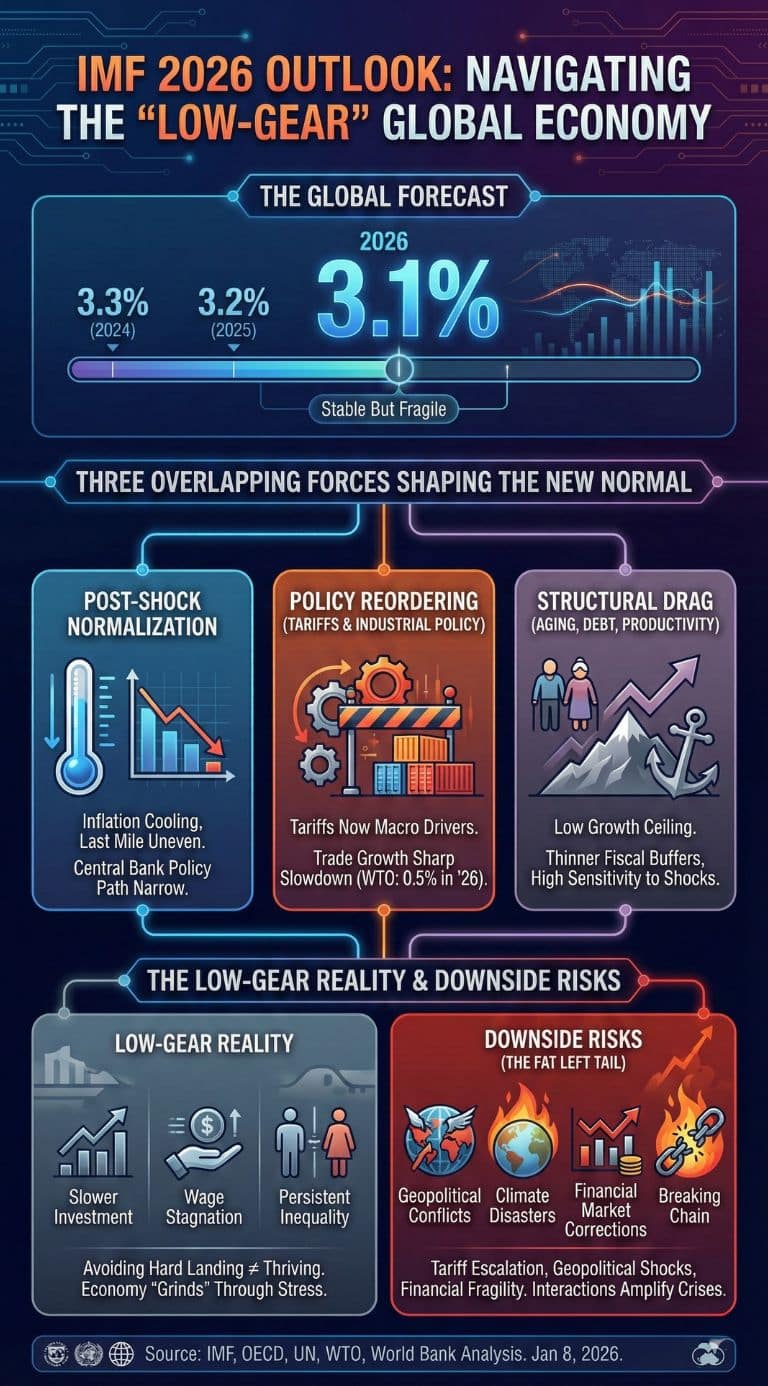

The IMF’s latest baseline frames 2026 as “stable but fragile.” In its October 2025 World Economic Outlook, the Fund projects global growth easing from 3.3% (2024) to 3.2% (2025) and 3.1% (2026), with advanced economies around 1.5% and emerging markets just above 4%. It explicitly flags that risks are tilted to the downside, citing uncertainty, protectionism, labor supply shocks, fiscal vulnerabilities, and potential market corrections.

If that sounds cautious, it is because 3.1% is not a return to the pre-pandemic “normal.” It is closer to a new equilibrium shaped by three overlapping forces:

-

Post-shock normalization: inflation has cooled from its peak, but the final leg back to targets is uneven.

-

Policy reordering: tariffs and industrial policy are no longer side stories; they are macro drivers.

-

Structural drag: aging, debt, and weak productivity keep the ceiling low, even when recessions are avoided.

The IMF’s July 2025 update makes the “why now” even clearer. It notes that the near-term upgrade reflected front-loading ahead of tariffs, lower effective tariff rates, better financial conditions, and fiscal expansion in major jurisdictions, while warning that downside risks from higher tariffs, uncertainty, and geopolitics persist.

Key Statistics That Define The Baseline

-

IMF: global growth projected 3.1% in 2026 (World Economic Outlook, Oct 2025; WEO Update, Jul 2025).

-

OECD: global growth projected 3.0% in 2026 (Interim Economic Outlook, Mar 2025), with tariff barriers and uncertainty weighing on demand.

-

UN DESA (WESP): world economy projected 2.5% in 2026, below the 2010–2019 pre-pandemic average of 3.2% (WESP update).

-

UNCTAD: global growth projected 2.6% in 2026, down from 2.9% (2024) (Trade and Development update, Dec 2025).

-

World Bank: global growth projected 2.3% in 2025; developing economies projected 3.9% average in 2026–27 (Global Economic Prospects, Jun 2025).

-

WTO: merchandise trade volume growth forecast 0.5% in 2026; it also reports world GDP growth (market exchange rates) 2.6% in 2026 (Global Trade Outlook update, Oct 2025).

| Forecaster | Publication (Latest Available As Of Jan 8, 2026) | Global Growth 2026 | What’s Driving The Call |

|---|---|---|---|

| IMF | World Economic Outlook (Oct 2025) | 3.1% | Subdued expansion, downside risks from protectionism and financial fragilities |

| OECD | Interim Economic Outlook (Mar 2025) | 3.0% | Higher trade barriers and policy uncertainty weigh on investment and spending |

| UN DESA | World Economic Situation and Prospects update | 2.5% | Challenging trade environment, heightened macro uncertainty; below pre-pandemic average |

| UNCTAD | Trade and Development outlook (Dec 2025) | 2.6% | Deteriorating policy environment, major-economy momentum loss |

| WTO | Global Trade Outlook (Oct 2025) | 2.6% (GDP, MER) | Cooling growth aligns with weaker trade and tariff transmission |

Why the range is so wide: “Global growth” is not a single, universal measure. Some institutions weight GDP by purchasing power (which gives fast-growing emerging economies more influence), while others emphasize market exchange rates, which often produce a lower headline number. That technical difference matters because it can shape investor and policymaker perceptions of momentum.

The Soft Landing Narrative Meets A Low-Gear Reality

The most important interpretation of 3.1% is not that the world is “fine,” but that the global economy may be settling into a low-growth corridor where shocks do not necessarily trigger immediate recessions, yet living standards rise more slowly and policy mistakes become more costly.

The World Bank frames this as a decade problem: if its forecasts materialize, average global growth in the first seven years of the 2020s would be the slowest since the 1960s. It also points to a longer-run downshift in developing-economy growth and trade growth, alongside record debt.

UNCTAD makes a similar point using a different yardstick: it projects global growth of 2.6% in 2025 and 2026 and notes this is below the pre-pandemic average (and below the longer pre-2008 era average it references).

The takeaway is that “soft landing” can be misleading. Avoiding a hard landing does not mean thriving. It can also mean the economy is absorbing stress by grinding: weaker productivity, slower investment, and persistent distributional tensions. That is where the downside risks become more than abstract possibilities. In a low-gear world, a shock does not need to be large to push outcomes off course.

Inflation Is Cooling, But The Last Mile Is Uneven

The IMF baseline assumes inflation continues to decline, but it also warns of “variation across countries” and highlights the United States as an upside inflation risk.

The analytical significance is this: the last mile of disinflation is rarely linear, and it is often where politics and supply constraints collide. Services inflation can remain sticky even when goods prices normalize. Labor supply shocks, which the IMF lists as a downside risk to growth, can also be an upside risk to inflation if they tighten markets unexpectedly.

The OECD adds detail on how this can play out: it notes lingering inflation pressures, weakening sentiment in some countries, and warns that fragmentation is a key concern. It also argues that higher trade barriers and uncertainty can weigh on investment and household spending, which can suppress demand but also complicate supply chains.

This is why the IMF’s 3.1% is tightly linked to interest-rate expectations. If disinflation stalls, central banks cut later or less. If inflation falls faster, cuts arrive sooner, easing financial conditions. Either way, the path is narrow because fiscal positions are weaker than in the last decade.

Trade And Industrial Policy Are Now Macro Variables

A decade ago, trade policy was often treated as a background assumption: globalization was not always smooth, but it was directionally expansive. The IMF’s recent language signals a shift. Its July 2025 update ties growth strength to front-loading ahead of tariffs and then stresses that potentially higher tariffs and uncertainty remain key downside risks.

The WTO’s October 2025 trade outlook quantifies what “tariffs as macro drivers” looks like:

-

Merchandise trade volume growth is forecast at 2.4% in 2025 but only 0.5% in 2026.

-

Commercial services export volume is forecast to grow 4.4% in 2026.

-

The WTO explains the mechanism: front-loading boosts trade early, then unwinds as inventories normalize and tariff effects are felt for a full year.

| Indicator | 2025 Forecast | 2026 Forecast | What It Suggests |

|---|---|---|---|

| Merchandise trade volume growth | 2.4% | 0.5% | A sharp cooling in the goods cycle as tariff effects spread |

| Commercial services export volume | 4.6% | 4.4% | Services remain steadier than goods, but momentum cools |

| World GDP growth (MER, WTO consensus) | 2.7% | 2.6% | Slower global expansion aligns with weaker trade intensity |

A New Twist: AI Is Supporting Trade, Not Just Services

One counterweight to tariff drag is the AI investment cycle. The WTO reports that trade in a defined basket of AI-related product lines expanded sharply, and it frames this as part of economies restructuring around AI.

That matters for the IMF story because it creates an unusual mix: geopolitics is fragmenting trade lanes while AI investment is stimulating cross-border demand for chips, servers, equipment, and digital infrastructure. The result is a trade cycle that can look resilient in the aggregate, while becoming more brittle underneath as “who trades with whom” changes faster than factories can.

Regional Divergence Is The Real Story Behind The Global Average

Global growth averages hide how uneven the distribution is. The IMF explicitly describes advanced economies at roughly 1.5% growth while emerging markets are just above 4%.

The OECD provides a concrete snapshot of how different the engines look:

-

United States: projected to slow to 1.6% in 2026

-

Euro area: projected at 1.2% in 2026

-

China: projected to slow to 4.4% in 2026

UNCTAD’s view is more downbeat for the largest economies as well, emphasizing deceleration and a more challenging policy environment.

| Economy/Bloc | OECD 2026 Growth (Where Available) | What It Implies For 2026 |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 1.6% | Demand cools, but the US still sets global financial conditions |

| Euro Area | 1.2% | Low growth keeps fiscal and political pressures elevated |

| China | 4.4% | Slower, more mature growth model reduces the global “import impulse” |

Interpretation: The world can hit 3.1% while many households experience something closer to stagnation, especially where population growth is low and debt service is high. That gap between “macro resilience” and “micro frustration” is where policy risk grows, including the temptation to use tariffs, subsidies, or capital controls in ways that can backfire.

Debt, Fiscal Expansion, And Financial Stability Are The Hidden Constraint

A key reason the IMF keeps stressing “downside risks” is that buffers are thinner. The July 2025 update notes fiscal expansion in major jurisdictions as one reason growth looked stronger in the near term. That is an honest admission that fiscal policy is still doing work in the baseline.

But the World Bank highlights the trade-off: investment growth has slowed, while debt has climbed to record levels, and developing economies face a tougher environment as trade barriers rise.

The BIS, in its June 2025 messaging, warns that trade tensions and heightened uncertainty can expose deeper fault lines in the global economy and financial system and calls on policymakers to act as a stabilizing force.

Why this is pivotal for 2026: When debt is high, the economy becomes more sensitive to changes in rates, spreads, and confidence. That increases the risk of “non-linear” events, sudden stops in capital flows, abrupt repricing of assets, or fiscal stress that forces pro-cyclical austerity. The IMF’s caution about fiscal vulnerabilities and market corrections fits this logic.

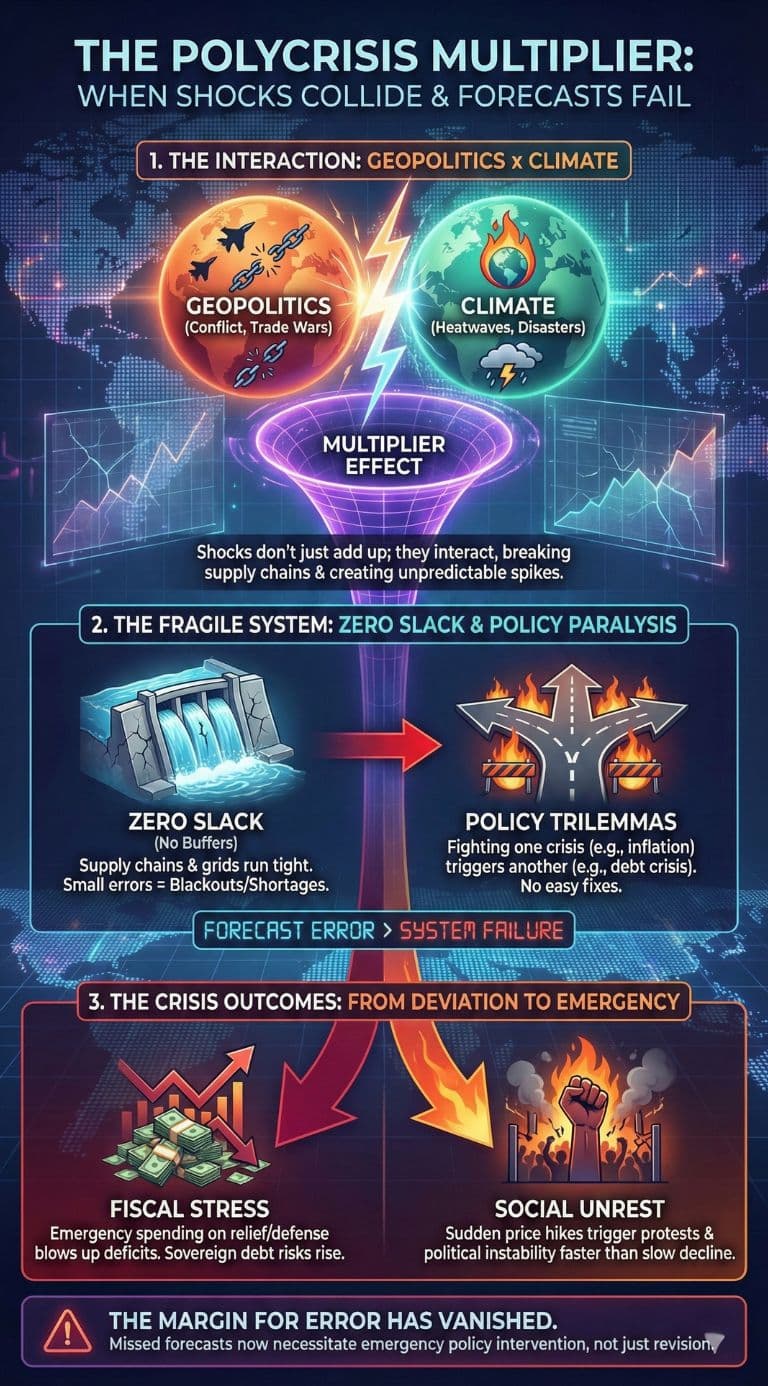

In other words, the downside risks are not only about growth being “a bit lower.” They are about the system’s ability to absorb shocks without turning a mild slowdown into a financial event.

Geopolitics And Climate Shocks Turn Forecast Errors Into Policy Crises

Forecasts fail most often when they underprice shocks. The IMF lists geopolitical tensions as a persistent downside risk. The World Bank emphasizes trade disputes and policy uncertainty as growth drags. The BIS focuses on uncertainty and the fraying of established economic ties.

What is changing is not that shocks exist. It is that they are interacting:

-

Tariffs can raise costs and reduce trade volumes, which can slow growth.

-

Slower growth worsens debt dynamics, making refinancing more fragile.

-

Fragility raises the stakes of any commodity spike, climate event, or regional conflict that disrupts supply.

This is why the “3.1% with downside risks” framing is less about predicting a recession and more about signaling that the distribution of outcomes is skewed: the baseline is steady, but the left tail is fat.

Expert Perspectives: Why Forecasters Disagree And Why You Should Care

Differences across forecasts are not just academic. They reveal what each institution believes is most binding:

-

IMF’s 3.1% reflects a world where emerging markets still carry a meaningful share of growth and where policy settings do not escalate into a full-blown trade spiral.

-

UN DESA’s 2.5% emphasizes a challenging trade environment and macro uncertainty and explicitly benchmarks the forecast against pre-pandemic averages, implying a more persistent slowdown.

-

UNCTAD’s 2.6% stresses a deteriorating policy environment and major-economy momentum loss.

-

WTO’s trade call is a warning about transmission: even if GDP stays positive, trade can slow sharply as tariffs bite, dragging manufacturing and investment.

-

OECD’s scenario work offers a quantified warning: in an illustrative escalation of bilateral tariffs, global output could be about 0.3% lower by the third year, with global inflation about 0.4 percentage points higher on average over the first three years.

| Downside Risk | What Could Trigger It | How It Hits The Economy | Who Is Most Exposed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tariff escalation and fragmentation | Broader or longer-lasting trade restrictions | Higher costs, weaker investment, trade slowdown | Export-dependent economies; manufacturing hubs |

| Inflation persistence | Services stickiness, supply constraints, labor shocks | Higher-for-longer rates, tighter credit | Highly leveraged firms and households |

| Fiscal stress | Higher rollover costs, weaker growth, political constraints | Forced tightening, instability, weaker safety nets | Highly indebted sovereigns; low-income states |

| Market correction | Abrupt repricing after optimistic valuations | Wealth effects, funding stress, confidence shock | Risk-asset-heavy markets; non-bank finance channels |

| Geopolitical and supply disruptions | Conflict, sanctions, shipping chokepoints | Commodity spikes, supply bottlenecks | Import-dependent countries; energy-sensitive sectors |

What Happens Next: The 2026 Milestones That Matter

If 2026 is a “tenuous resilience” year, the critical question is what turns resilience into durability. Three milestones are likely to define whether the IMF baseline holds.

Whether Trade Policy Settles Or Spirals

The IMF’s own narrative suggests part of the 2025 uplift came from tariff-related distortions like front-loading, which by definition fade. The WTO projects that the tariff impact becomes more visible in 2026, pushing trade growth sharply lower.

Watch for signals that policy uncertainty is being reduced through clearer rules, narrower measures, or negotiated resets.

Whether Rate Cuts Arrive Without A Second Inflation Wave

The “last mile” question will shape consumer credit, housing, and corporate refinancing. The IMF’s warning about US inflation staying above target is a reminder that a global easing cycle may not be synchronized.

A staggered easing path tends to amplify currency and capital-flow volatility, especially for emerging markets.

Whether Debt Risks Stay Contained

The World Bank’s warning about record debt and slowing investment, plus the BIS focus on uncertainty and financial fault lines, suggests the world is more vulnerable to a confidence shock than the baseline implies.

In 2026, the “test” is not only default risk. It is whether governments can protect growth without losing market credibility.

Final Thoughts

If the IMF’s IMF 2026 Global Growth Forecast of 3.1% holds, it will likely be because policymakers manage to do something that has been rare in recent years: reduce uncertainty. That does not mean eliminating risk. It means creating enough predictability that businesses invest, supply chains adapt, and central banks can normalize policy without whiplash.

The more realistic near-term outlook is a world where growth remains positive but uneven, trade becomes more politically managed, and the price of policy mistakes rises because fiscal and financial buffers are thinner. In that setting, “downside risks” are not a footnote. They are the central story