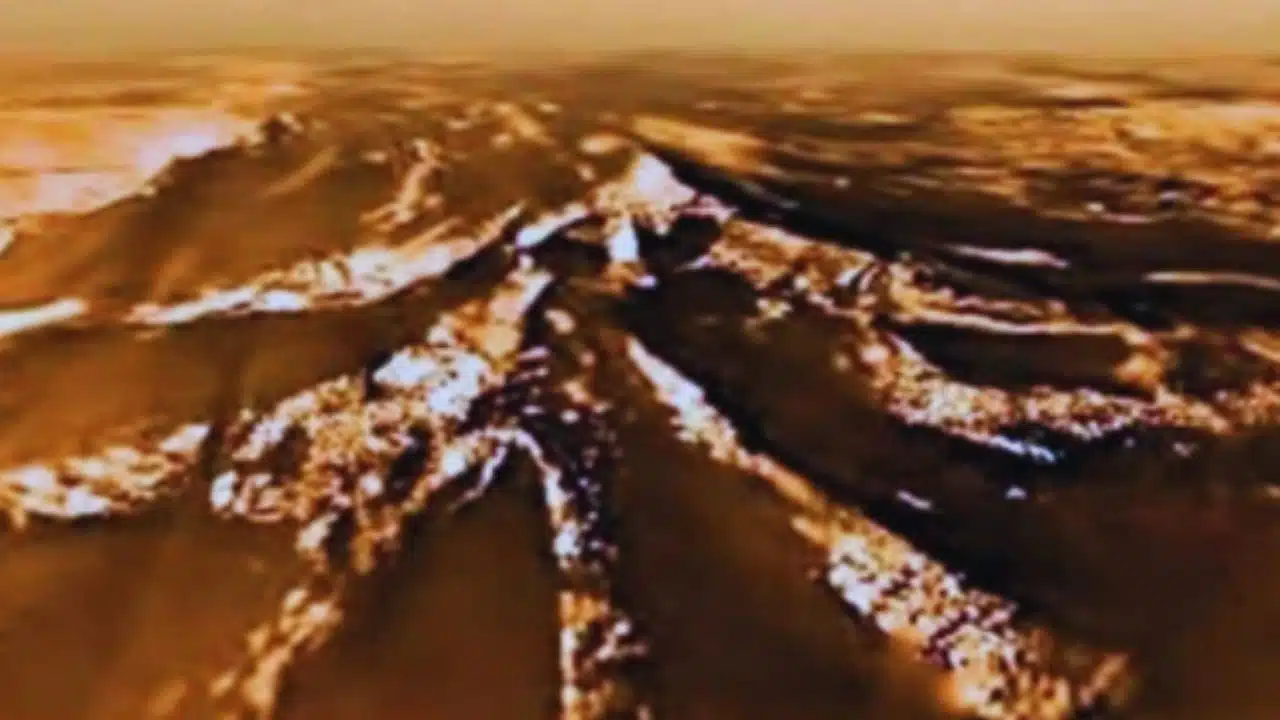

On 14 January 2005, the Huygens probe — part of the joint Cassini–Huygens mission by the European Space Agency and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) — made history by descending through the thick, orange-hued atmosphere of Titan, the largest moon of Saturn. During the roughly 2.5 hour descent, the probe captured a series of images of Titan’s surface. Among them was a photograph taken from an altitude of about 8 kilometres above the surface, showing a striking boundary between lighter, uplifted terrain criss-crossed with branching channels and darker, lower-lying plains.

This image continues to fascinate scientists two decades later, because while it strongly suggests familiar Earth-like erosion and drainage patterns, how such features formed under Titan’s incredibly cold conditions remains uncertain.

What the image reveals

The panorama from near the surface of Titan shows terrain that appears quite familiar — yet is alien in every chemical and thermal sense. The brighter, elevated terrain appears dissected by narrow, branching channels, many of which appear to converge into broader depressions or basin-like features. These dark lower areas resemble dried-up deltas or ancient lakebeds. At the landing site (near the equatorial region known as Adiri), the probe found rounded pebbles made of water ice and a substrate whose mechanical behaviour resembled “damp sand”.

On Titan, surface temperatures hover around –179 °C (approximately –290 °F) and liquid water is frozen solid; instead, the role of fluid erosion appears to be played by liquid methane and ethane, supplemented by atmospheric rains of hydrocarbons. Indeed, the atmosphere of Titan is composed mostly of nitrogen (≈ 98.4 %) with a few percent of methane — and the descent measured these components directly. The image taken by Huygens gives the strongest visual evidence yet of an active, albeit cold, hydrological cycle on Titan: fluid channels, deltas, flow features.

What makes the image so compelling is the implied geological activity: channels cut into terrain, basins downstream, evidence of fluid transport, deposition, and possibly seasonal change. In other words: an alien world with processes analogous to those on Earth, but under conditions vastly different.

Why scientists are still puzzled

Despite the clarity of the photograph and the wealth of ancillary data, many fundamental questions about the formation of those branching channels on Titan remain unresolved:

- Timing and frequency of flows: We don’t know when those channels formed, how often fluids moved through them, or whether they are still active. On Earth, river systems can re-shape a landscape over seasons or centuries. On Titan, the relevant time scale is far less constrained and may span thousands or millions of years.

- Fluid source and paths: The channels look like they were carved by flowing fluid, but the source is ambiguous. Possibilities include methane rainfall on the uplands, underground methane springs emerging to the surface, or perhaps even cryovolcanic events (where cold liquids or slurries erupt from Titan’s interior). Because Huygens landed far from the large methane/ethane seas found at Titan’s poles, the origin and destination of the supposed flows are puzzling.

- Surface vs subsurface interplay: The mechanical structure at the landing site — ice pebbles in a damp-sand-like soil — suggests that surface fluids interacted with sediments. But how deep the liquid infiltration goes, how the subsurface responds, and whether there is a hidden reservoir remain open questions.

- Single image limitation: Though spectacular, the image came from one descent path in one location at one time. Without long-duration surface operations or multiple sites, it is difficult to generalise how representative that terrain is of Titan as a whole, or how it has evolved.

In sum, while the image gives undeniable hints of familiar erosional and depositional processes, the exact mechanisms, rates, driver dynamics, and past vs present activity are still hotly debated.

What’s next: future missions and broader context

The Huygens image is not just a curiosity—it points to how much there is still to learn about Titan, and by extension about how planetary surfaces evolve in very different environments. Here’s what comes next and why it matters:

A future mission, the Dragonfly rotorcraft lander, is scheduled to launch in 2028 and arrive at Titan in the early 2030s. Unlike Huygens (which made a single site landing and lasted only about 72 minutes on the surface), Dragonfly will fly across dozens of locations over more than three years, analysing surface chemistry, subsurface interactions, the presence of complex organics, and the interplay of geology and hydrology. The hope is that we will go from a snapshot to a comprehensive field study of Titan’s complexity.

In the broader context, Titan stands out as the only body in the solar system, outside Earth, known to have a dense atmosphere and surface liquids (even if those liquids are hydrocarbons, not water). As such, it provides a valuable natural laboratory: how does an Earth-like morphologic process (fluid erosion, channel formation, deposition) operate under radically different temperature, chemistry and gravity regimes? And what can that tell us about planetary evolution, climate cycles, habitability and even the potential for life (or pre-life chemistries) in exotic environments?

Why this matters—scientific, exploratory and for journalism

For scientists, the persistent puzzle of the Titan image underscores a key lesson that planetary exploration is never “done” once a probe lands. A single mission may open more questions than it answers—especially when dealing with worlds radically different from Earth.

For explorers and mission planners, the image reminds us of the value of long-duration, mobile platforms (rovers, flyovers, atmospheric craft) and of sampling multiple locations, especially on moons or planets where one site may not reflect the global picture.

For you, as a journalist and media-entrepreneur connected to global science and technology themes, the story offers rich angles:

- The power of international collaboration: Huygens was led by ESA, carried by Cassini (NASA), showing how partnerships extend our reach into deep space.

- The long game in science: the image came in 2005, yet scientists are still analysing, still debating, and still awaiting future missions to clarify the picture. This is a 20-year legacy story.

- The broader impact: communicating to general audiences how alien worlds can nonetheless mirror familiar processes, and what that teaches us about Earth, about climate, geological time and our place in the cosmos.