Have you ever noticed new parks or green buildings popping up in your neighborhood, only to see old neighbors slowly pushed out? Maybe rent has gone up, or the small shops you loved now sit empty. Change can feel exciting at first, yet pricey upgrades may force families to leave their homes. I’ve seen this happen in cities across the US, and it raises a tough question: who really benefits when a neighborhood goes “green”?

Did you know that some eco-friendly projects meant to help cities stay healthy can actually make life harder for the people who already live there? This phenomenon, known as “eco-gentrification,” is a growing problem where city leaders build more gardens and stylish apartments but forget about long-time residents.

Let’s walk through exactly why this happens, how it affects your community’s health and housing costs, and the practical steps we can take to fix it together.

What is Eco-Gentrification?

Eco-gentrification happens when “green” buildings and parks push out long-time residents. It sounds helpful, but it often shifts problems instead of fixing them.

Definition and Etymology

Eco-gentrification mixes the word “ecology,” which means studying nature, with “gentrification,” a term that describes what happens when wealthier people move into an area and change it.

The roots of “gentrification” go back to British sociologist Ruth Glass in 1964, who used it to show how middle-class groups pushed out working-class residents. But the “eco” twist is newer. In 2009, researcher Sarah Dooling coined the term “ecological gentrification” to describe how vulnerable groups, like the homeless, were displaced from public parks to make way for environmental improvements.

Sometimes, city leaders use sustainable architecture or urban greening projects, hoping to boost community health and create better green spaces. While these changes help the environment, they often raise property values too fast for low-income neighbors, pricing them out of their homes.

Social justice groups worry about losing affordable housing and cultural identity as eco-friendly plans reshape cities.

How it Differs from Traditional Gentrification

After talking about what the term means and where it comes from, we should see how this new trend stands apart. Traditional gentrification often centers on fixing old buildings or making a neighborhood look better for wealthier people.

Here, things usually start with private investors or developers who want to make money from property values going up.

Green building flips that pattern. Cities push plans for urban sustainability, like parks or bike lanes. These projects sound great, but can end up raising rents fast. People in low-income areas may have to leave as costs go up around new green spaces, even though these changes started with public goals like cleaner air or community health.

This twist puts social equity at risk while shining a light on environmental justice issues tied to economic growth and housing affordability everywhere cities invest in “greener” futures.

The Connection Between Green Building and Eco-Gentrification

New parks and green roofs can make a city look fresh, but they often make living there expensive. People who once called these places home may find themselves priced out, searching for new roots elsewhere.

Role of Urban Greening Projects

Urban greening projects brighten city blocks with trees, parks, and gardens. They boost air quality and reduce heat. In New York City, the High Line turned old tracks into a green park; it now draws millions each year.

Green spaces seem to promise better health for nearby residents and even spark urban renewal. Yet, as these projects grow, property values can climb fast. A study by the US Forest Service found that just planting trees on a street can increase home prices by thousands of dollars.

Higher prices push out low-income families who once lived in those areas. A leafy street sometimes leads to rising rent signs popping up next door. Some people lose their homes or sense of belonging when new buildings pop up, or houses get flipped for profit.

Now we move on to how these changes affect communities at their core; social impacts are closer than they appear.

Increased Property Values and Displacement

Green buildings and new parks can raise property values in many neighborhoods. Homeowners may cheer, but renters often face trouble. Rents go up fast, pricing out families who have lived there for years.

“In Atlanta, housing prices near the southwest side of the BeltLine trail skyrocketed by over 60% in just a four-year span, according to local real estate reports.”

In some cities like New York, after the High Line opened, rent nearby jumped by more than 30% within a few years. Longtime residents may feel squeezed as big changes hit their blocks.

Stores that once sold affordable goods are closing up shop. Wealthier neighbors move in looking for “green” spaces and modern design. Low-income communities sometimes get pushed further away from schools or jobs they depend on daily.

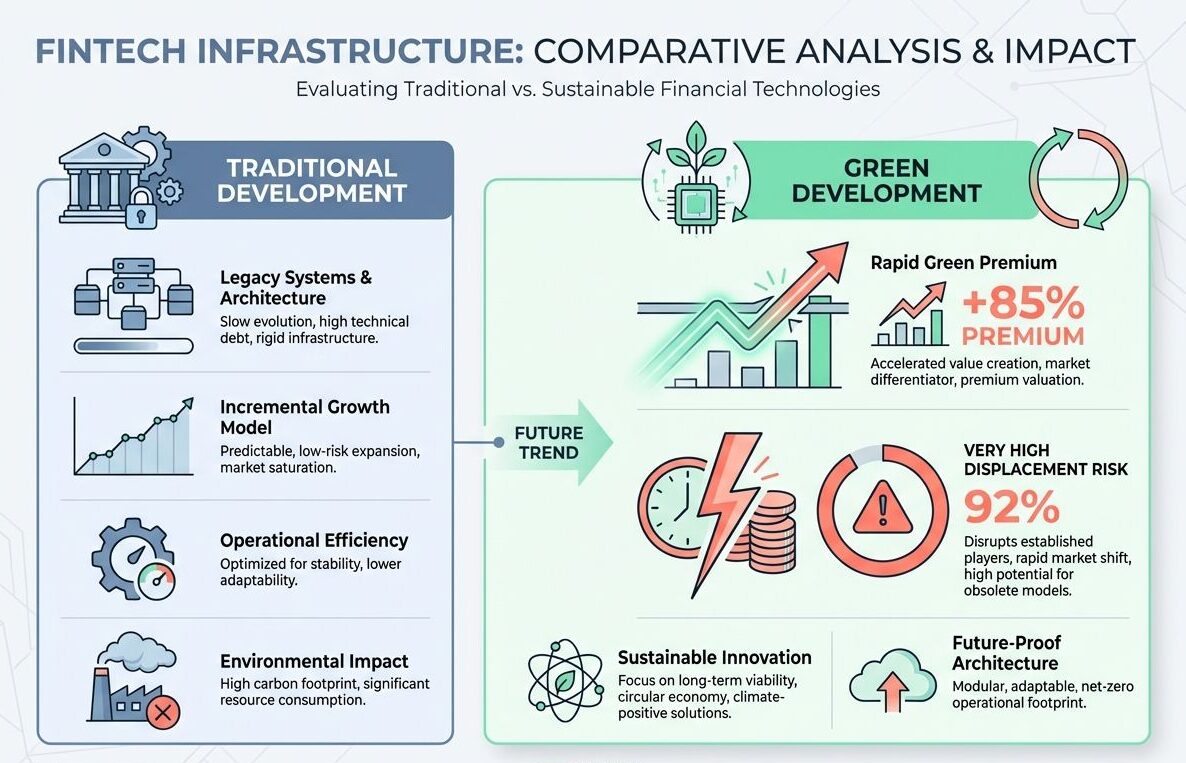

| Feature | Traditional Development | Green Development |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Profit & Density | Sustainability & Health |

| Price Impact | Gradual increase | Rapid “Green Premium” spikes |

| Displacement Risk | High | Very High (due to desirability) |

Social Impacts of Eco-Gentrification

Green upgrades can push people out of their own neighborhoods, leaving them feeling like strangers on their own turf. These changes often tip the balance, making daily living harder for those with less money.

Displacement of Low-Income Communities

Urban development projects can make homes and parks greener, but they often push out families who have lived there for years. As property values rise, rent goes up fast. Low-income residents may lose their homes because they cannot pay the new prices.

This forces them to move far from friends, jobs, and schools. In cities like New York, eco-gentrification connected to places such as The High Line led to thousands of working-class renters being priced out.

This loss does more than just take away a roof; it breaks apart close communities and disrupts daily life routines. Many people feel angry or powerless because decisions are made without asking those most affected. These changes widen gaps between rich and poor neighbors while claiming to help everyone equally through green building projects.

Loss of Cultural Identity

Long-time residents move out, new groups move in, and local traditions start to fade. Community events, family-run shops, and old murals get replaced by trendy cafes or fancy buildings.

- Street Names Change: Historic markers are often rebranded to sound more “marketable.”

- Local Flavors Vanish: Affordable diners are replaced by high-end chains.

- Community Silence: The music and festivals that defined a block often disappear as noise complaints from new residents rise.

In neighborhoods like Harlem or parts of Barcelona, eco-gentrification pushes out stories that made the area special for decades. Songs sung on corners in Spanish or Creole turn quiet as rents rise with green spaces. Festivals shrink because people can no longer afford to stay near their roots.

Widening Socioeconomic Inequalities

Green building projects can raise property values fast, making homes in these areas too expensive for many families with lower incomes. As new parks and clean spaces pop up, living costs often shoot up like weeds after the rain.

Rent hikes push out people who once called these neighborhoods home, while wealthier newcomers move in. This shift creates a bigger gap between richer and poorer residents.

Eco-gentrification often hits minority communities the hardest, leading to fewer chances for affordable housing or steady jobs nearby. Local shops that serve long-time residents may close as new businesses target those with more money to spend. These changes hurt community bonds and make it tough for everyone to enjoy equal access to green spaces and healthy environments promised by urban sustainability efforts.

Examples of Eco-Gentrification

Many cities have seen shiny new parks and green rooftops change who gets to live nearby. To see these changes in action, check out real-life stories where new trees and trails sparked more than just fresh air.

The High Line in New York City

The High Line opened in 2009 as a public park built on an old rail line. It runs for about 1.5 miles above Manhattan’s West Side, weaving through city buildings and art installations.

Tourists love the fresh air, gardens, and skyline views. But property values shot up nearby after it opened; some long-time residents had to move out because rents rose too fast. In fact, housing values in the immediate area increased by 35% shortly after the park’s completion, outpacing the rest of the city.

This green space brought fresh life to the area, but changed who could afford to live there. Small shops closed or were turned into expensive restaurants and galleries. Some people call this eco-gentrification, a pretty garden with hidden costs for working families and low-income neighbors seeking affordable housing options in urban development projects like this one.

Urban Greening in Barcelona

Green roofs and gardens have sprung up all around Barcelona since 2013. The city calls this effort the “Pla del Verd i de la Biodiversitat.” It offers tax breaks to building owners who add plants or green spaces.

These projects make neighborhoods cooler, cleaner, and nicer to look at. But property values rise fast in these greener areas. Low-income families often get priced out of their own blocks. Older markets, murals, and local bars disappear as new cafés move in.

Streets once full of neighbors turn quiet with short-term rentals instead of long-time residents. This has sparked protests from groups calling for more affordable housing while keeping urban sustainability plans strong, issues also seen in Green Initiatives in Vancouver.

Green Initiatives in Vancouver

Vancouver pushes hard for urban sustainability. The city set a goal to become the greenest city in the world by 2020. New buildings must follow green building codes, aiming to cut greenhouse gases.

Developers add rooftop gardens and bike paths, which look great but often raise property values fast. Many low-income families get priced out of these neighborhoods as rent climbs higher.

Community groups fight for affordable housing so old residents can stay put. The effects ripple through local culture and public spaces too, changing who uses parks and shops nearby. People want greener cities, but also fair treatment for everyone living there now.

Addressing the Challenges of Eco-Gentrification

Cities can build green spaces while keeping neighborhoods fair and welcoming, so keep reading to see how this balance plays out.

Balancing Urban Sustainability with Social Equity

Green buildings can make places cleaner and healthier. It often raises property values. This growth may push out families who have lived there a long time. People with less money often cannot afford the new rent.

Strong urban sustainability goals should walk hand-in-hand with social justice plans. Cities must protect affordable housing during green projects, so new parks or bike paths do not mean fewer homes for regular folks.

Everyone deserves a healthy space to live, not just those who can pay top dollar for it. Fair rules help keep communities together as they grow greener and stronger.

Implementing Inclusive Urban Planning Policies

Striking a balance between urban sustainability and social equity sets the stage for fair city growth. Planners can help by making rules that protect lower-income people. Cities like Portland have tried mixed-income housing, which lets families from many backgrounds live side by side.

Community voices matter, so listening to local input shapes better neighborhoods. Some cities use “inclusionary zoning.” This makes developers save a part of new buildings for affordable units. Boston adopted this in 2000, leading to over 1,500 affordable homes just in its first ten years.

Clear policies about green spaces can protect long-term residents too; parks and gardens should not push people out but invite everyone in.

Protecting Affordable Housing

Smart urban planning sets the table, but keeping affordable housing on the menu takes steady work. Cities like New York and Vancouver have seen green spaces push up property values fast. This can force families out of once-affordable homes quicker than you might expect.

One powerful tool is the Community Land Trust (CLT). In Houston, for example, the local CLT program has helped families buy new, three-bedroom homes for around $75,000, permanently protecting them from market spikes.

Laws that limit rent hikes also help slow down this trend. Some places use “inclusionary zoning” rules to make developers build lower-cost apartments along with new projects. Community land trusts keep prices stable by letting residents control who lives in each home, blocking big investors from buying up whole neighborhoods for profit.

These steps don’t stop economic growth or urban development; they just help everyone enjoy greener cities together.

The Role of Environmental Justice in Green Building

Fairness matters when we talk about who gets clean parks, fresh air, and safe homes. If green projects leave some folks out in the cold, are we really building better cities?

Aligning Sustainability Goals with Social Justice

Eco-gentrification can push out people who have lived in a neighborhood for years. Green buildings, parks, and new bike lanes often raise property values and rents. Low-income families may lose their homes as a result.

Planners must protect affordable housing so all groups benefit from urban sustainability projects. Including local voices in city planning helps keep cultural identity strong.

Cities like New York and Vancouver face these issues right now. Public policies can help balance green spaces with social justice goals by giving everyone fair access to safer streets, clean air, and healthy parks. Working on environmental equity means making sure changes serve the whole community, no matter their background or income level.

Ensuring Access to Green Spaces for All

Many families in cities cannot use the parks and gardens near their homes. New green spaces often raise rent, push out longtime neighbors, and widen the gap between rich and poor.

Trees or clean air should never be a luxury for only some people. Low-income communities deserve safe paths to nature, too, not just fancy bike lanes that lead nowhere for them.

City leaders can protect affordable housing next to new parks. Clever plans include community voices from start to finish. Fair rules help prevent displacement as neighborhoods change. Protecting access for all is key before moving on to how social justice goals connect with building green places.

Wrapping Up

Eco-gentrification changes neighborhoods in big ways. It can lift property values and bring green spaces to life. However, it also drives out low-income families and hurts local cultures if we aren’t careful. Simple steps like fair urban planning and strict rules for affordable homes help keep the balance. Let’s build cities where nature thrives, people stay rooted, and no one gets left behind.