In mid-19th-century Bengal, one scholar used simple words and careful logic to fight a painful custom. Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar argued that Hindu widows should be free to remarry. He did not shout. He wrote. He wrote pamphlets and letters in clear Bengali. He cited Hindu scriptures and commentaries. He appealed to compassion (dayā) and the common good. His campaign moved from print to public meetings and then to the legislature.

In July 1856, the Hindu Widows’ Remarriage Act (Act XV of 1856) became law across Company-ruled India, making such marriages legally valid and protecting the legitimacy of their children. The fight did not end social stigma, but it changed the legal ground and the moral tone of the debate.

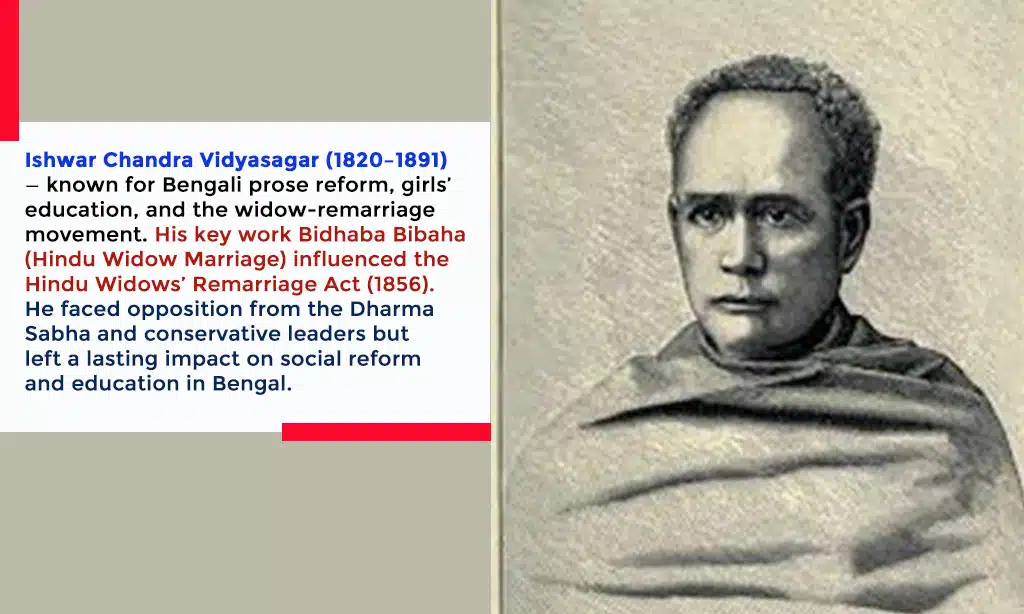

Quick facts at a glance

| Item | Details |

| Full name | Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar (1820–1891) |

| Known for | Bengali prose reform; girls’ education; widow-remarriage movement |

| Key text | Bidhaba Bibaha (Hindu Widow Marriage) — pamphlet/tracts |

| Law influenced | Hindu Widows’ Remarriage Act (Act XV of 1856) |

| Opponents | Conservative leaders and associations, including the Dharma Sabha |

| Legacy | Lasting influence on social reform and education in Bengal and beyond |

Bengal, Orthodoxy, and a Reformer

Mid-19th-century Calcutta was a loud laboratory of change. Steam presses were cheap, public meetings were common, and readers argued through letters as eagerly as leaders did from podiums. New schools promised mobility while older hierarchies guarded status and inheritance. The abolition of sati (1829) had shown that custom could bend, but it also hardened conservative resolve. Into this arena stepped Vidyasagar: a scholar fluent in Sanskrit logic and the new vernacular prose, able to speak to priests and printers in the same breath.

Bengal Renaissance & Social Conservatism

The period often called the Bengal Renaissance witnessed the growth of print culture, new schools, and reformist thought. Reformers sought education for wider groups and pushed back against customs that harmed women and lower castes. Conservative elites, however, organized to defend tradition and social order. In this climate, widow remarriage became a flashpoint. The question was simple: should a young widow be forced into a life of deprivation, or could she legally start again?

At a glance

| Topic | Key points |

| Print culture | Pamphlets and newspapers amplified public debate |

| Reform energy | Education, women’s rights, legal change gained momentum |

| Conservative pushback | Defense of custom; worries about lineage and property |

| Public forum | Meetings, petitions, and the press shaped opinion |

Vidyasagar’s Formation

Vidyasagar studied at Sanskrit College in Calcutta, earned the honorific “Vidyasagar” (“Ocean of Learning”), served as head pandit at Fort William College (1850), and later became principal of Sanskrit College (1851). He opened the doors to lower-caste students, wrote clear Bengali prose, and compiled the classic primer Barnaparichay. His scholarship gave him unusual authority to interpret shastras for the public good—and to carry those arguments into everyday Bengali.

| Role | Details |

| Scholar | Master of Sanskrit and Bengali; honored as “Vidyasagar” |

| Educator | Expanded access at Sanskrit College; improved curriculum |

| Language reform | Simplified Bengali prose; wrote popular primers |

| Public intellectual | Used pamphlets and newspapers to argue for reform |

The Letters: How Vidyasagar Argued in Public

Pamphlets were the social media of that era—quick to print, easy to pass around, and written to spark reply. Vidyasagar used them with care. He wrote as if addressing a neighbor: clear claims, short proofs, and an invitation to think again. He anticipated objections and answered them in serial installments, which kept the conversation alive and the audience returning. His letters created a steady rhythm—argument, counterargument, clarification—that trained readers to weigh texts against lived experience.

Pamphlets & Newspaper Letters

Under titles such as “Bidhaba Bibaha” (Hindu Widow Marriage), Vidyasagar presented a case for reform that was both textual and ethical. He also sent letters to newspapers and replied to critics, creating a public dialogue that reached beyond elite circles. Digitized editions of these tracts show his blend of shastric citation and plain style.

At a glance

| Element | Role in the movement |

| Pamphlets (Bidhaba Bibaha) | Core arguments with sources |

| Newspaper letters | Timely replies that sustained momentum |

| Printing presses | Enabled wide, fast distribution |

| Public readings | Brought literate and semi-literate audiences into the debate |

Style & Strategy

Vidyasagar worked on three levels:

- Scriptural interpretation. He read across smritis and commentaries, arguing that compassion and social welfare justify widow remarriage.

- Plain language. He used direct Bengali prose so non-specialists could follow the logic.

- Ethical appeal. He asked readers to consider widows’ suffering, not only textual disputes.

Summary table

| Tool | How he used it | Why it mattered |

| Shastric citations | Contextual reading; weighing authorities | Challenged blanket claims of prohibition |

| Clear Bengali | Short sentences; vivid examples | Expanded the audience for reform |

| Public letters | Serial replies to objections | Kept debate moving and accessible |

Sample Excerpts

Even in translation, the thrust is clear: a humane reading of tradition is part of dharma. The pamphlets argue that public good should guide application of texts, and that legalization would reduce harm. Today’s digitized scans let readers see the typography, tone, and cadence of those arguments as they first appeared.

At a glance

| Excerpt theme | What it shows |

| Appeal to compassion | The moral core of the case |

| Reference to smriti | Legitimacy within tradition |

| Call to action | Pressure for opinion and policy to change |

The Debates: Shastras, Logic, and Social Need

The fiercest disputes were not only about what a verse “said,” but how to read it in a changing society. Vidyasagar framed interpretation as a craft: compare authorities, weigh context, and test the outcome against the duty to reduce harm. His opponents appealed to stability; he appealed to responsibility. What made these exchanges influential was the method—start from shared sources, proceed with reason, and end with care for the vulnerable.

Vidyasagar’s Hermeneutics

He argued that dharma includes compassion and that different authorities within the dharmaśāstra tradition allow room for widow remarriage under social need. He compared commentaries, noted diversity of practice, and insisted that texts must be read together, not in isolation. This did not reject tradition; it used tradition to reach a humane outcome.

Reading the texts: a quick map

| Source type | How he engaged it | Practical effect |

| Dharmashastra | Contextual reading; humane priorities | Opened doctrinal space for reform |

| Commentaries | Compared alternate views | Showed tradition is not monolithic |

| Custom & precedent | Cited diversity in practice | Undercut rigid claims of uniform ban |

Orthodox Counter-Arguments

Conservative leaders and associations, including the Dharma Sabha founded by Radhakanta Deb (1830), opposed the proposal. They argued that widow remarriage would violate scripture, threaten family order, and disrupt inheritance. They organized petitions and public meetings against reform. Their visibility in Calcutta’s public sphere gave the debates high stakes and wide reach.

| Orthodox claim | Vidyasagar’s reply |

| Shastras forbid widow remarriage | Some authorities allow it; dayā (compassion) is central to dharma |

| Family order will collapse | Legal clarity can reduce disorder and protect children |

| Reform is a Western import | Arguments arise within Hindu texts and ethics |

| Social chaos will follow | Regulated, lawful remarriage reduces harm and stigma |

Public Meetings & Opinion

Meetings in Calcutta and district towns, editorials in the press, and petitions to the Legislative Council turned the debate into a mass conversation. The controversy also spurred counter-associations and responses in print. The government, sensitive to public opinion and administrative need, could not ignore the scale of the discussion.

How debate spread

| Channel | Impact |

| Sabhas and assemblies | Mobilized supporters; signaled community stance |

| Newspapers | Shaped urban opinion; preserved arguments |

| Petitions | Carried the issue to the state |

| Pamphlets | Offered detailed cases for or against reform |

From Agitation to Law: Act XV of 1856

Legislation did not arrive as a thunderclap. It built like pressure—petition by petition, speech by speech, editorial by editorial. The colonial council had to decide whether law should ratify a humane option already argued in public or keep obstructing it. The 1856 Act chose clarity. It recognized that families needed rules they could trust and that widows needed a legal path to a new life. The statute turned a moral case into civil protection.

Petitions, Memorials, and Press Pressure

Vidyasagar’s memorials and pamphlets pushed the case. Conservative petitions pushed back. Council debates weighed doctrine, custom, and public good. The administration framed the Act as removing legal obstacles rather than imposing remarriage on anyone, a position that acknowledged both sides while privileging freedom of choice.

Path to the Act

| Step | What happened |

| Public agitation | Pamphlets, letters, meetings, and newspaper debates |

| Petitions & counter-petitions | Reformers vs. Dharma Sabha and allies |

| Council deliberation | Doctrine, custom, and welfare considered |

| Enactment | Act XV of 1856 removed legal obstacles |

What the Act Changed (Plain English)

The Act made a widow’s remarriage lawful and valid. It clarified inheritance effects: in general, a widow who remarried lost some claims in the deceased husband’s estate, but her new marriage and children were recognized as legitimate. The text also stressed that consent of an adult widow was sufficient for a lawful remarriage.

Key provisions in brief

| Provision | Plain-language meaning |

| Validity | A widow’s remarriage is legal; children are legitimate |

| Consent | An adult widow’s consent is enough to remarry |

| Property | Certain claims in the deceased husband’s estate cease on remarriage |

| Scope | Applied across Company-ruled India to Hindus |

Immediate Reactions

Reformers celebrated; conservatives warned of disorder. Many families still refused remarriage due to stigma and pressure. Yet the Act gave legal cover to those who chose it and signaled a shift in official policy. Over time, the law influenced attitudes and reduced uncertainty for families who acted on the new right.

Reaction summary

| Group | Response |

| Reformers | Welcomed legal recognition and moral precedent |

| Conservative sabhas | Continued to discourage practice |

| General public | Change was slow; stigma persisted |

| Government | Framed law as removing obstacles, not imposing change |

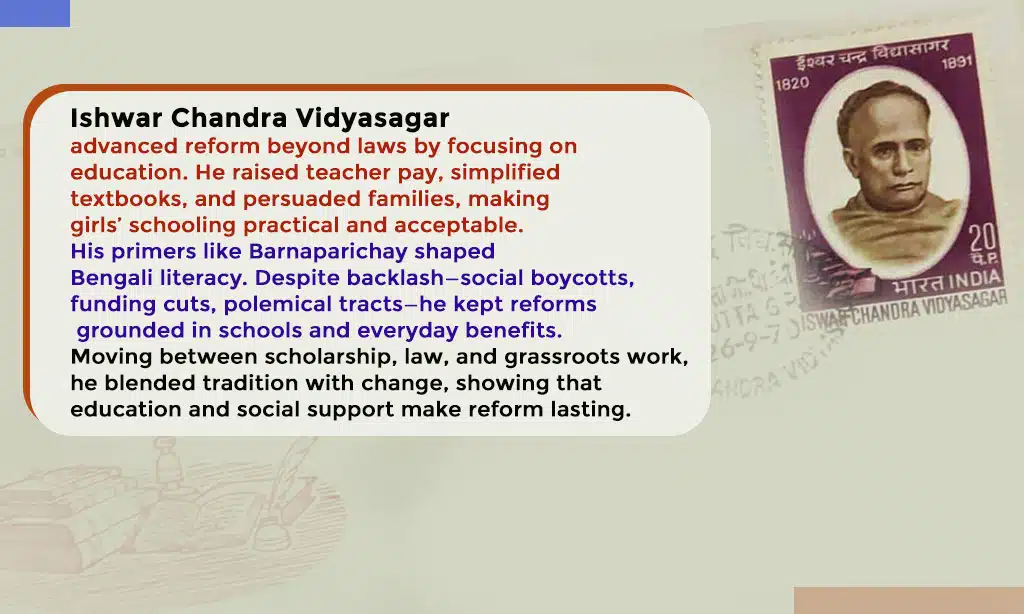

Beyond Marriage: Education & Backlash

Reform is brittle without schools. Vidyasagar knew this, which is why he worked on the unglamorous details—teacher salaries, textbook language, and community persuasion. Girls’ education became the long engine of his short campaign. The more families saw practical value in literacy and numeracy, the less persuasive the old fears felt. Predictably, backlash followed: whispers, withdrawals of funding, and pamphlets that tried to shame supporters. He answered not by escalating rhetoric, but by making the schools harder to ignore.

Girls’ Schools & Curriculum Design

He supported schools for girls and designed textbooks with simple language. His readers—especially Barnaparichay—helped shape Bengali literacy for generations. He also balanced tradition and modern subjects, easing families into new ideas without discarding their values.

Education efforts

| Area | Actions |

| Access | Admitted students from lower castes at Sanskrit College |

| Girls’ schooling | Funded and supported schools; persuaded families |

| Language | Developed clear Bengali prose; primers and readers |

| Curriculum | Balanced classical and modern subjects |

Resistance & Retaliation

Orthodox groups used social pressure, funding withdrawals, and polemical tracts. Critics tried to portray reform as a betrayal of faith. Yet by keeping the focus on schools and practical benefits, Vidyasagar built a base of everyday support that outlasted pamphlet wars.

Forms of backlash

| Tactic | Effect |

| Social boycott | Isolated reformers and families |

| Funding pressure | Hurt schools and charities |

| Polemical tracts | Swayed elite and conservative opinion |

| Personal attacks | Tried to delegitimize leadership |

A Pragmatic Reformer

Vidyasagar moved between Sanskrit scholarship, vernacular prose, government councils, and grassroots philanthropy. He believed laws matter, but education and social support make change real. His life shows a deliberate blend of ideas and institutions: argue for reform, then make it usable in daily life.

Pragmatism in action

| Sphere | Approach |

| Texts | Argue from within tradition |

| Law | Remove legal barriers |

| Schools | Expand access; write better books |

| Public | Keep debate civil, simple, and humane |

Defiance in Practice: Schools, Funds, and Relief

It is easier to debate principles than to pay fees, raise buildings, or arrange scholarships. Vidyasagar did the latter. He turned subscribers into stakeholders and sympathizers into sponsors. His relief efforts during local crises stitched reform to compassion in the public mind. When people saw him spend his own resources, they understood his arguments as more than words. Defiance, in his case, meant a steady habit of service that made retreat—his or society’s—look smaller and smaller.

Service snapshot

| Area | Examples |

| Scholarships | Helped poor students continue education |

| Widow support | Quiet assistance; moral and material |

| Institution building | Backed schools and libraries |

| Relief work | Responded during local distress |

Why service mattered

| Reason | Impact |

| Credibility | A reformer who sacrificed was trusted |

| Visibility | Showed reform as care, not only argument |

| Community ties | Built support networks for change |

| Continuity | Helped reforms outlast backlash cycles |

Myths vs. Facts

History gets flattened when told only as heroes and villains. The widow-remarriage story is subtler: customs varied by region; practices changed unevenly; and law, while vital, never acted alone. This section separates common shortcuts from the record. It shows how “tradition” often holds competing voices and how reformers like Vidyasagar argued from within that chorus. By clearing away myths, readers can see what actually changed—and what it took to change it.

Myth 1: “Widow remarriage started only after 1856.”

Fact: Some remarriage customs existed locally, but the Act of 1856 legalized remarriage across Company-ruled India, clarified inheritance, and protected children’s legitimacy. Law turned scattered practice into a recognized civil right.

Myth 2: “Vidyasagar opposed tradition.”

Fact: He argued from tradition, citing Hindu authorities and using dharmic ethics of compassion and public good to support reform.

Myth 3: “The Act instantly changed society.”

Fact: Change was slow. Stigma and family pressure remained. Legal reform opened the door; education, advocacy, and support helped people walk through it over time.

Quick guide

| Myth | Reality |

| Reform was anti-Hindu | Reform drew on Hindu texts and ethics |

| Law ended debate | Debate continued for decades |

| Change was immediate | Practice lagged; culture shifts slowly |

Timeline (1820–1891)

Timelines help the eye grasp what prose can blur: sequence, pace, and overlap. Here, dates anchor the movement to specific moments—textbooks next to tracts, meetings beside memorials, and finally a law that codified a right. The milestones reveal a pattern: language reforms prepared the audience; public argument swelled opinion; institutions sustained momentum.

| Year | Event |

| 1820 | Vidyasagar born at Birsingha (Sept 26) |

| 1840s | Early career; head pandit at Fort William College; focus on language and education |

| 1851 | Principal of Sanskrit College; advocates broader access |

| 1855 | Publishes tracts supporting widow remarriage (Bidhaba Bibaha) |

| 1856 | Act XV passed; legalizes widow remarriage under Company rule |

| 1860s–70s | Continued work in education; charitable efforts; rural initiatives |

| 1891 | Dies in Calcutta (July 29) |

Orthodox Claims vs. Vidyasagar’s Rebuttals

Arguments travel better when they are easy to scan. This table reduces the debate to its moving parts: a claim, the worry beneath it, the counter-reasoning, and the practical effect after 1856. Side by side, you can see how a moral case becomes a legal framework—and how that framework reduces confusion in daily life.

| Orthodox claim | Source of concern | Vidyasagar’s rebuttal | Practical outcome |

| Scriptural ban | Texts read in isolation | Other authorities and principles allow compassion-guided remarriage | Opened doctrinal space |

| Family order at risk | Lineage and control | Legal clarity protects families and children | New legal framework |

| Property will be lost | Widow’s claim vs. lineage | Act clarifies consequences while validating marriage | Predictable rules |

| Western imitation | Colonial influence | Arguments arise within Hindu texts and ethics | Reform as indigenous |

Takeaways

Reform rarely arrives as a perfect victory; it arrives as a better floor to stand on. Vidyasagar built that floor plank by plank—argument, school, statute, service. The opposition did not disappear, but it had to argue on new ground. That is the real legacy: a public taught to test tradition by its care for the living, and a path showing how scholarship and empathy can change the everyday.

Closing thought:

Vidyasagar proved that a reformer does not need loudness to be strong. He needed patience, sources, and a steady voice that combined scholarship with kindness. That mix changed law and, slowly, life.