Venezuela oil exports are effectively frozen at the worst possible time for Caracas and the best possible time for a market already swimming in crude. A U.S. blockade, tanker seizures, and new sanctions are now colliding with a global oversupply, reshaping who gets Venezuelan barrels and what leverage they buy.

How We Got Here

Venezuela’s oil story is a long arc from abundance to constraint. It holds some of the world’s largest proven reserves, dominated by extra-heavy crude in the Orinoco Belt, but production capability has been hollowed out by years of underinvestment, operational decay, and sanctions pressure.

The U.S. sanctions architecture tightened sharply after Washington designated PDVSA in January 2019 and then broadened restrictions later in 2019. While the U.S. later issued waivers and licenses that allowed limited flows under specific conditions, the overall effect was to push most Venezuelan exports into discounted, sanctions-evasion channels and toward non-U.S. buyers.

That evolution matters because Venezuelan crude is not “plug-and-play.” Much of it is extra-heavy, meaning it requires diluents like naphtha to move through pipelines and be exportable at scale. Over time, sanctions and geopolitics reshaped not only who bought Venezuelan oil, but also who supplied the ingredients needed to make exports physically possible.

In late 2025, Washington’s approach shifted from mostly financial and licensing pressure to more direct maritime enforcement. On December 31, 2025, the U.S. Treasury sanctioned four companies and identified four tankers as blocked property, explicitly framing them as part of a “shadow fleet” that generates revenue for Maduro’s government.

By early January 2026, the situation escalated again. Reporting described an “ongoing U.S. oil blockade” that drove exports to a standstill, forcing PDVSA to begin cutting production as storage filled and diluents ran short.

Key Statistics That Define The Moment

- Venezuela produced about 1.1 million bpd in November 2025 and exported about 950,000 bpd that month, but shipments fell to roughly 500,000 bpd in December 2025 based on ship movements.

- PDVSA has about 48 million barrels of onshore storage capacity, with reported stocks surpassing 45% of that capacity, plus more than 17 million barrels stuck in ships as floating storage.

- The U.S. Treasury’s December 31, 2025 action named the tankers NORD STAR, ROSALIND (aka LUNAR TIDE), DELLA, and VALIANT and linked them to sanctioned entities.

- In early January 2026, Brent traded around $60 and WTI around $57 even as Venezuela’s political and export crisis deepened.

- U.S. crude imports from Venezuela averaged 132,000 bpd in 2020 and 228,000 bpd in 2021 (annual EIA series), illustrating how quickly flows can swing based on policy and licensing.

Supply Shock In A Glut: Why Prices Fell Instead Of Spiking

In a different oil market, an abrupt disruption in Venezuelan exports would typically spark a risk premium. Venezuela is an OPEC member, and a sudden loss of hundreds of thousands of barrels per day would usually tighten the heavy-sour segment in particular.

But early 2026 is not a “tight” market. Multiple outlooks and market commentary have framed 2026 as a year of oversupply, after oil prices suffered a steep decline through 2025. The key point is not just that supply is ample, but that traders believe replacement barrels exist, either through spare capacity, inventory, or non-OPEC growth.

That helps explain the seemingly counterintuitive reaction: oil prices note the chaos, but drift lower because global supplies are viewed as adequate and because the longer-term implication of a Venezuelan political transition is more oil later, not less oil now.

This is how the futures curve can “look through” a short-term blockade. If the market believes the next phase involves partial sanctions relief or even direct U.S. influence over Venezuelan oil policy, then the dominant signal is potential future supply growth. Analysts have described regime change as a major upside risk to global supply over 2026–2027 and beyond, with long-run scenarios that could meaningfully pressure prices if Venezuela climbs toward 2 million bpd over time.

The analytical takeaway: the market is pricing Venezuela less as a near-term supply outage and more as an option on future barrels. In a well-supplied market, “future barrels” can matter more than “today’s disruption.”

The Mechanics Of A Modern Oil Embargo: Tankers, Blending, And Storage Math

An “exports freeze” sounds like a political choice. In Venezuela’s case, it becomes a physical constraint chain:

Tanker access is the bottleneck

Venezuela relies on tankers to export. When sanctioned vessels are blocked or seized, and risk rises for shipping companies and insurers, exports can collapse quickly even if oil is still being produced. Late-December designations were aimed directly at the intermediary ecosystem that keeps sanctioned barrels moving.

Diluents are a second choke point

Reports described PDVSA running short of diluents needed to blend heavy crude for shipment. When naphtha or light oil supply is disrupted, production itself can be forced down even if wells are capable of pumping. Orinoco output’s dependence on imported diluent is a structural vulnerability: pressure one logistics node (shipping), and the blending chemistry breaks downstream.

Storage becomes the “hard stop”

Once tanks fill, the system seizes. Reporting described PDVSA moving toward shut-ins as onshore tanks filled, with tens of millions of barrels either in tanks or stranded offshore. At that point, “exports frozen” is no longer a headline. It is operational triage: shutting down clusters, throttling joint ventures, and risking downstream disruptions that can spill into domestic fuel supply.

Before Vs. After: Export And Storage Stress

| Metric | Pre-Crackdown Snapshot | Late-2025 / Early-2026 Snapshot |

| Oil exports (approx.) | ~950,000 bpd (Nov 2025) | ~500,000 bpd (Dec 2025) and then effectively halted under blockade conditions |

| Floating storage | Manageable | >17 million barrels waiting offshore |

| Onshore storage capacity use | Normal operating range | >45% of 48 million barrels cited as filled, with spillover measures reported |

The shift is less about geology and more about logistics.

Winners And Losers: The Trade Re-Routes Are The Story

When Venezuelan barrels move, the identity of the buyer is not just a commercial detail. It signals who holds leverage.

As sanctions reduced U.S. intake, Chinese buyers became dominant. A reversal could reroute barrels back to U.S. refiners, especially on the Gulf Coast where complex refineries can process heavy grades efficiently.

At the same time, “shadow trade” typically creates large discounts. That discount is an economic weapon: it rewards buyers willing to take sanctions risk (often smaller refiners and trading networks) and punishes a producer that needs cash and has limited market access.

A blockade-plus-sanctions approach seeks to break that discount system by raising the cost of evasion.

The objective is straightforward: reduce regime revenue by targeting the intermediary ecosystem.

Who Gains And Who Pays

| Likely Winners | Why | Likely Losers | Why |

| U.S. Gulf Coast refiners (complex heavy-crude processors) | Potential access to heavy crude if flows normalize under compliant channels | Chinese independent refiners and intermediaries tied to discounted barrels | Lose discounted supply and face higher sanctions/shipping risk |

| Non-Venezuelan heavy crude suppliers (Canada, Mexico, Middle East sour grades) | Gain pricing power if Venezuelan heavy supply stays constrained | PDVSA and Venezuela’s fiscal accounts | Revenue loss, operational shut-ins, storage crunch |

| Sanctions-compliant shippers/insurers | Benefit as risky “shadow fleet” capacity is penalized | Sanctioned tanker networks and oil traders | Asset blocking, trade disruption, escalating enforcement risk |

This is a redistribution story: not just barrels, but margins, discounts, and bargaining power.

Domestic Fallout: Oil Revenues Are Not Optional For Caracas

Venezuela’s economy is unusually sensitive to oil export continuity because oil is not merely an export sector. It is the state’s financial spine.

Recent policy and research summaries have cited IMF estimates that Venezuela’s GDP contracted by more than 80% from 2013 to 2020, alongside persistent poverty and humanitarian need, with millions requiring assistance. That matters for the current oil freeze for three reasons:

Revenue loss quickly becomes political fragility

An interim leadership that cannot pay salaries, fund patronage networks, or stabilize fuel supply is vulnerable, regardless of rhetoric. Reporting warned of a “domino effect” from production cutbacks into refining and domestic fuel supply.

Humanitarian constraints tighten

When exports stall, imports of fuel components, food, medicine, and basic goods can become harder to finance, especially if banking channels are constrained by sanctions risk.

Migration pressure rises

The scale of Venezuelan displacement is already regional in impact. When oil income becomes less reliable, the push factors that drive outward migration intensify.

A crucial nuance: sanctions and embargoes are often evaluated in geopolitical terms, but their fastest effects are macroeconomic and social. Even a short disruption can matter because Venezuela has little cushion.

Sanctions As Statecraft: From Paper Restrictions To Maritime Enforcement

The most consequential shift in this episode is not a new legal paragraph. It is the move from compliance pressure to enforcement reality.

Late-2025 actions did two things at once: they punished specific entities and tankers, and they warned the broader market that Venezuelan oil exposure carries rising sanctions risk.

Meanwhile, reporting suggested blockade dynamics that complicated even flows associated with licensed operations—at least temporarily—highlighting that exemptions can be overwhelmed by operational realities at sea. From an analytical standpoint, this resembles patterns seen in other sanctions regimes where pressure migrates from banks to ships, and then governments target the logistics layer.

The question is not whether sanctions can reduce exports. They clearly can. The question is whether enforcement produces political outcomes or simply reconfigures illicit trade networks over time.

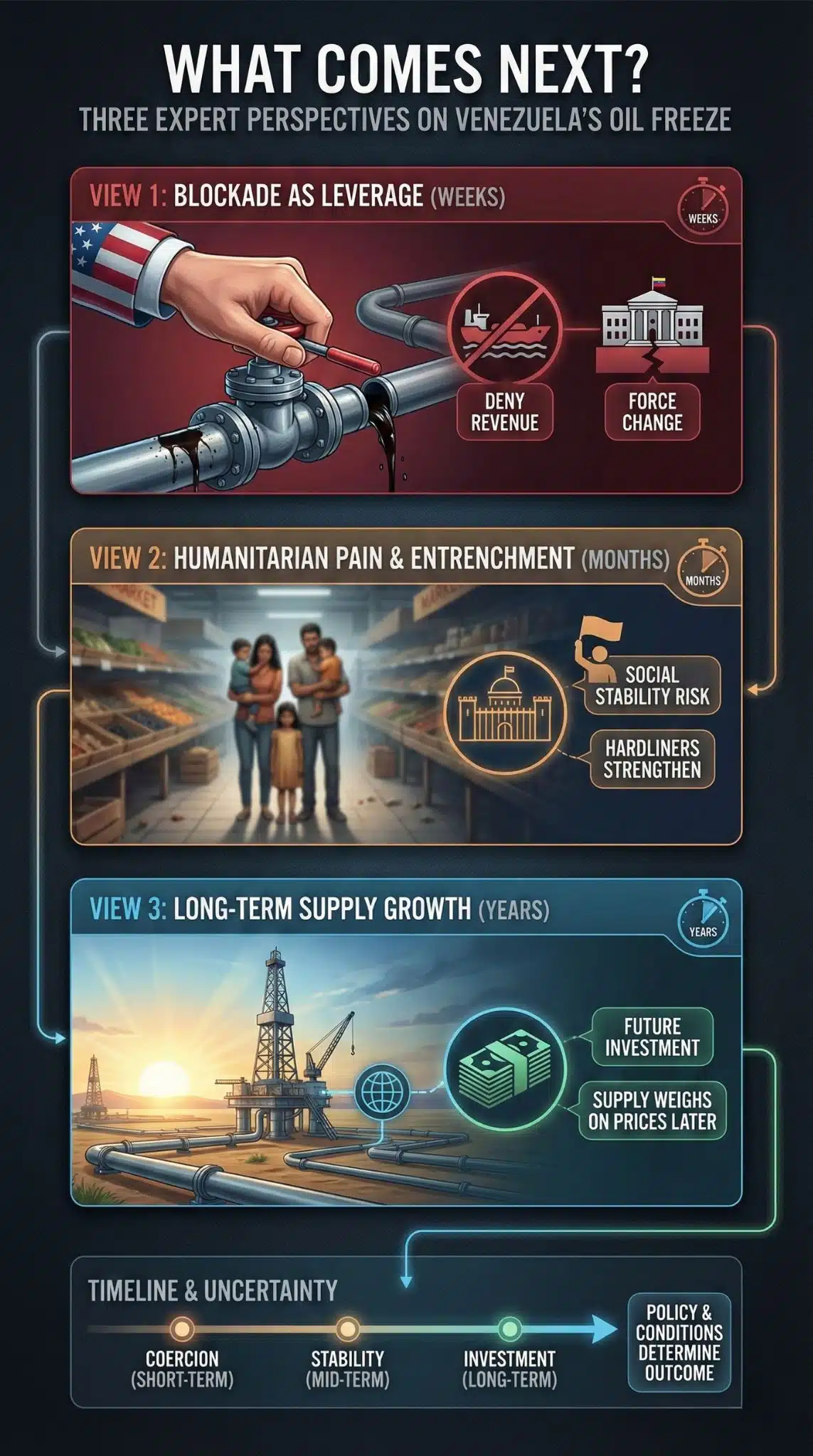

Expert Perspectives: Why Serious Analysts Disagree On “What Comes Next”

A credible analysis has to hold two ideas at once:

View 1: The blockade is leverage that could force change

Proponents argue that oil revenue is the regime’s lifeline, and that targeting intermediaries cuts directly into survival finance. The argument is simple: deny revenue, reduce resilience, force concessions.

View 2: Enforcement can deepen humanitarian pain and entrench hardliners

Critics argue that economic strangulation can strengthen the most coercive actors while ordinary households absorb the shock. If the country’s humanitarian baseline is already fragile, sudden revenue loss can be socially destabilizing rather than politically liberating.

View 3: Markets think the “real” impact is long-term supply growth

This view is visible in price action and in analyst notes: if political transition unlocks investment, Venezuelan production could rise materially over several years, weighing on prices later even if today’s exports are stuck.

These views conflict because they focus on different timelines: weeks (coercion), months (social stability), or years (investment and supply).

A Comparative Timeline Of Escalation And Its Market Meaning

| Date | Event | Why It Changed The Outlook |

| Jan 2019 | PDVSA sanctioned | Pushed exports into constrained channels and accelerated infrastructure decay through underinvestment |

| 2022–2023 | Limited waivers and licensed flows resume | Reopened a controlled pathway for some barrels to reach U.S. refiners |

| Mar 2025 | License adjustments and wind-down language | Signaled policy volatility and tighter tolerance |

| Dec 31, 2025 | Sanctions on traders and identification of tankers | Targeted logistics infrastructure, increasing shipping and compliance risk |

| Early Jan 2026 | Export standstill and output cuts reported | Turned sanctions pressure into an operational storage crisis |

The Look Ahead: Three Scenarios For 2026 And The Milestones To Watch

What happens next depends less on geology than on policy credibility, security conditions, and whether international operators believe contracts and payments are enforceable.

Scenario 1: Prolonged Export Paralysis (Weeks To Months)

If blockade conditions persist and sanctioned tanker access remains constrained, PDVSA is likely to deepen shut-ins because storage and diluent shortages are hard physical limits. That raises the risk of domestic fuel disruptions and a sharper fiscal crisis.

Milestones to watch

- Shipping signals: whether tankers return to load and whether floating storage declines

- Additional sanctions actions on maritime firms and vessels

- Visible refinery impacts inside Venezuela (fuel scarcity or rationing)

Scenario 2: Managed Re-Opening Under Strict Oversight (Months)

A negotiated mechanism could allow exports through a narrower set of compliant ships and buyers, potentially tied to political concessions, escrow arrangements, or humanitarian carve-outs.

Milestones to watch

- Any new general licenses or formal guidance affecting oil transactions and payment channels

- Whether U.S. imports from Venezuela trend up or down in official series

- Evidence of diluent availability improving (a quiet but decisive signal)

Scenario 3: Gradual Production Recovery After Political Transition (Years)

Here, the key is investment. Banks and oilfield service firms will not return at scale without credible contract enforcement and an accepted political settlement. Even optimistic scenarios imply years of work: repair of upgraders, pipelines, and power supply; reliable diluent access; and debt restructuring.

Production And Price Scenarios (Illustrative, Not Certainties)

| Scenario | Venezuela Output Path | Market Impact | What Would Have To Be True |

| Stagnation | Flat to lower (storage-led shut-ins) | Minimal global price impact in a glut, big domestic impact | Blockade persists, diluents constrained, no durable deal |

| Partial normalization | Stabilize, modest growth | Heavy crude spreads tighten, trade routes rewire | Licenses and compliant shipping channels expand |

| Recovery | 1.3–1.4 mbpd in ~2 years, longer-run upside | Adds meaningful future supply, pressure on long-dated prices | Political settlement, investment, enforceable contracts |

Final Thoughts

The Venezuela oil exports freeze is not only a country crisis. It is a test case for a broader global trend: sanctions enforcement migrating from banks to ships, and from rules to operational choke points.

It also reveals a new market reality. In an oversupplied world, supply disruptions do not automatically raise prices. Sometimes they lower them—because the market is looking past the outage and pricing in the possibility of larger future flows.

For policymakers, the hard question is whether coercion at sea delivers political outcomes on land, or whether it simply rearranges trade into ever more opaque channels while Venezuela’s humanitarian situation deteriorates. For markets, the question is whether Venezuela becomes the next latent supply wave that matters more in 2027 than in 2026.