On December 3, 1999, Bangladesh lost one of its gentlest and most creative souls. Rokonuzzaman Khan, whom generations know simply as Dadabhai, passed away in Dhaka, leaving behind a world of rhymes, stories, and smiling readers.

On his twenty-sixth death anniversary, his presence is still vivid. You hear it in children chanting Hattimatim Tim in school assemblies. You see it in the logo of Kochi Kanchar Asar in The Daily Ittefaq. You feel it whenever someone recalls the warmth of “Dadabhai” writing back to young readers.

This tribute is an attempt to remember him in full. As a journalist who shaped a generation. As a children’s writer who made nonsense meaningful. As an organizer, I transformed a newspaper page into a nationwide movement for children. And as a kind mentor who believed that every child carried a spark of genius.

Early Life: A Literary Childhood

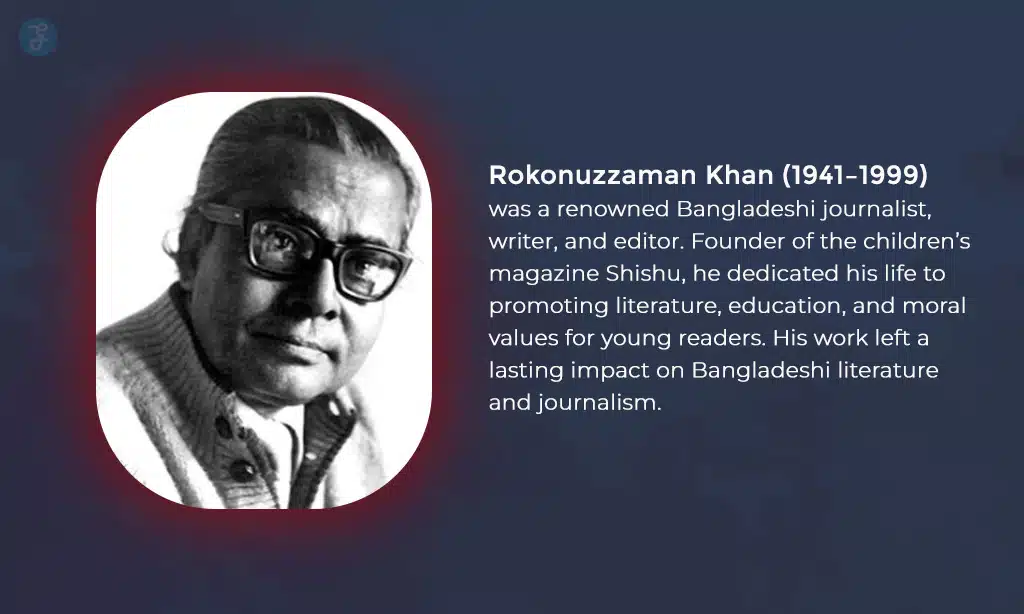

Rokonuzzaman Khan was born on 9 April 1925 in Pangsha, in what is now Rajbari District, then part of Faridpur in Bengal Presidency.

He grew up in a literary family. His grandfather, Mohammad Rawshan Ali Chowdhury, edited the monthly magazine Kohinoor, and other relatives, such as Yakub Ali Chowdhury and Rowshan Ali Chowdhury, were also involved in writing and publishing.

In such a home, magazines, proofs, and manuscripts were part of daily life. It is no surprise that young Rokonuzzaman was drawn to letters very early. He saw how stories and essays could travel far beyond the village and how a printed page could connect people who never met in person.

That sense of print as a bridge stayed with him all his life. Later, when he wrote for children, he never treated the newspaper page as something distant or cold. For him, it was a living meeting place between “Dadabhai” and thousands of young minds.

Finding His Voice in Journalism

Dadabhai’s formal journey in journalism began soon after Partition. He worked at the Daily Ittehad in Kolkata in 1947, then at Shishu Saogat in 1949 and The Millat in 1951. In those newsrooms, he took charge of special sections for young readers

- Mitali Majlis in Ittehad

- Kishor Duniya in The Millat

This early focus on children’s content is important. Many journalists move into children’s writing later in their careers. Dadabhai chose it almost from the beginning. He saw children not as a side audience but as a central public that deserved its own style, rhythm, and respect.

In 1955, he joined The Daily Ittefaq, which was emerging as one of the most influential newspapers in East Pakistan. He worked first on the Mufassil (district) pages and then moved deeply into what would become his life’s work.

Kachi Kanchar Asar: Turning a Newspaper Page into a Childhood Home

At Ittefaq, Rokonuzzaman Khan took charge of the children’s page Kachi Kanchar Asar. It was here that he adopted the pen name “Dadabhai”, meaning elder brother. Very soon, readers forgot his official name and knew only the affectionate one.

Kachi Kanchar Asar was more than a page of fun. Under Dadabhai’s careful editing, it became

- A platform for children’s own writing

- A nursery for young poets, storytellers, and cartoonists

- A friendly advice space where children sent letters about their fears and dreams

- A cultural bridge between urban and rural children through shared rhymes and stories

He edited the page from 1955 until his death in 1999. For more than four decades, countless children grew up sending their “first writing” to Dadabhai. Many later became authors, journalists, teachers, and artists, often tracing their confidence back to seeing their name printed in that section.

Dadabhai not only published polished submissions. He corrected, guided, and nurtured. His famous anthology “Amar Prothom Lekha” collected the first published pieces of several writers, showing how the page had become a launchpad for serious literary careers.

Kachi Kanchar Mela: From Page to Movement

A page was not enough for Dadabhai. He wanted children to meet face-to-face, sing, act, and build friendships. Out of this dream grew Kachi Kanchar Mela. Formed in the mid-1950s and formally organized in the 1960s, Kachi Kanchar Mela became one of the most important children’s cultural organizations in Bangladesh. It organised

- Storytelling and recitation events

- Drawing, music, and drama programs

- National gatherings at its central building in Dhaka

- Regional circles that carried the spirit of the Asar across the country

Writers and cultural figures such as Sufia Kamal and others supported the early growth of the organization, but Dadabhai was widely recognized as its main architect and guiding force.

For children, Kachi Kanchar Mela was a second home. It gave many their first stage, their first audience, and their first sense of collective identity as young citizens of a new nation.

The Magic of Dadabhai’s Rhymes

Some of his best-loved works include

- Hattimatim (1962)

- Khokon Khokon Dak Pari

- Ajob Holeo Gujob Noy

- Collections such as Jhikimiki

These rhymes are often grouped as “nonsense verse” in a playful sense, similar to how English nursery rhymes work. Yet under the surface, they teach rhythm, language, and a quiet sense of order. Children learn sound, pattern, and memory even when they are only laughing at the strange images.

His language was always simple but never flat. He mixed everyday words with poetic inventiveness in a way that felt natural to children. Many adults, when they quote these poems, feel an instant wave of nostalgia, proof that the rhymes live deep in the memory of the country.

A Mentor Without a Formal Classroom

Although Dadabhai did not teach in a school or college, he functioned as a teacher for many thousands of children. Through Kachi Kanchar Asar and Kachi Kanchar Mela, he played several roles at once

- Editor who corrected spelling, grammar, and structure

- A coach who encouraged shy children to submit their first work

- A moral guide who promoted honesty, kindness, and patriotism

- A cultural worker who linked children to national events and values

Writers who came of age in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s often recall how a short note in the margin from “Dadabhai” changed the way they saw their own ability. He rarely scolded sharply. Instead, he nudged, praised, and suggested improvements.

He also understood how lonely childhood could feel, especially in uncertain times. His page carried not only poems and drawings but also little pieces of advice and comfort. For children who did not have rich libraries at home, Kachi Kanchar Asar was a weekly window into a kinder, larger world.

Family Life and Creative Partnership

Dadabhai married Nurjahan Begum, the pioneering female journalist and editor of the women’s magazine Begum and the daughter of Mohammad Nasiruddin, founder of Saogat and Begum.

It was a rare literary partnership. In one household, children’s literature, women’s journalism, and progressive cultural movements came together. Both partners believed that reading and writing could change lives and that underrepresented voices needed their own platforms.

Their family environment helped nurture more creative work in later generations as well. In recent years, members of the family have continued to promote travel, culture, and the image of Bangladesh abroad in new media formats, showing how the spirit of outreach has adapted to new times.

Awards and National Recognition

The state and literary institutions of Bangladesh eventually recognized what ordinary readers had known for decades. Dadabhai’s services to children’s literature and journalism were honoured with

- Bangla Academy Literary Award in 1968

- Shishu Academy Award in 1994

- Ekushey Padak in 1998

- Independence Day Award in 2000, given posthumously

He also received other honors, such as the Jasimuddin Gold Medal and the Paul Harris Fellow recognition from Rotary, which underline how widely his contributions were valued.

Yet if you asked him, he might have pointed not to medals but to the shelf where he stored stacks of letters from children. That was his real award. Proof that he had reached the minds and hearts of the next generation.

3 Reasons Why Dadabhai Still Matters 26 Years Later!

The world children grow up in today is very different from the one Dadabhai knew. Screens have replaced many printed pages. Attention spans are shorter. Commercial content is everywhere.

Yet his work remains relevant for at least three reasons.

1. He treated children with respect

Dadabhai never spoke down to children. He believed they could understand subtle emotions and complex values if you spoke to them honestly and with warmth. That attitude is still a model for all who write or design content for young audiences.

2. He built community, not just content

Through Kachi Kanchar Asar and Kachi Kanchar Mela, he created a sense of belonging. In a time when children often feel isolated behind screens, his approach reminds us that creativity grows best in community, not in isolation.

3. He showed that “small” genres are not small at all

Many societies treat children’s literature as less serious than adult writing. Dadabhai’s life proves the opposite. The stories and rhymes we hear first stay with us longest. They shape our sense of language, humor, justice, and self.

On his twenty-sixth death anniversary, revisiting his work is not only an act of memory. It is a way to ask hard questions about how we treat children today. Do we still give them time to imagine, to read, to write, to send a first nervous poem out into the world, and wait for a kind reply

Frequently Asked Questions on Rokonuzzaman Khan Dadabhai

Here are the most frequently asked questions people have about Rokonuzzaman Khan Dadabhai.

Who was Rokonuzzaman Khan, also known as Dadabhai?

Rokonuzzaman Khan was a Bangladeshi journalist, children’s writer, and organizer, born on 9 April 1925 in Pangsha, Rajbari. He became famous under the pen name “Dadabhai” as the long-serving editor of the children’s page Kachi Kanchar Asar in The Daily Ittefaq and as the founder and key architect of the children’s organization Kachi Kanchar Mela.

What is Dadabhai best known for?

He is best known for his playful rhymes like Hattimatim Tim, his children’s books such as Hattimatim, Khokon Khokon Dak Pari, and Ajob Holeo Gujob Noy, and for his decades of work running Kachi Kanchar Asar, where he nurtured children’s writing and art and encouraged reading across Bangladesh.

What was Kachi Kanchar Mela?

Kachi Kanchar Mela is a nationwide children’s cultural organization in Bangladesh. It grew out of the community around Kachi Kanchar Asar in the 1950s and 1960s. Under Dadabhai’s leadership, it organized events, workshops, and performances that helped young people develop confidence, creativity, and a sense of national identity.

Which awards did Rokonuzzaman Khan receive?

He received many major honors, including the Bangla Academy Literary Award in 1968, the Shishu Academy Award in 1994, the Ekushey Padak in 1998, and the Independence Day Award in 2000, given after his death. These awards recognize his lifelong service to children’s literature and journalism.

How can we honor Dadabhai’s legacy today?

We can honor his legacy by keeping his books in circulation, reading his rhymes with children, supporting children’s cultural organizations, and treating young readers with the same respect and care that he did. Encouraging children to write, draw, and share their work is perhaps the most faithful tribute to the man who once edited “Amar Prothom Lekha” and believed that every first attempt mattered.