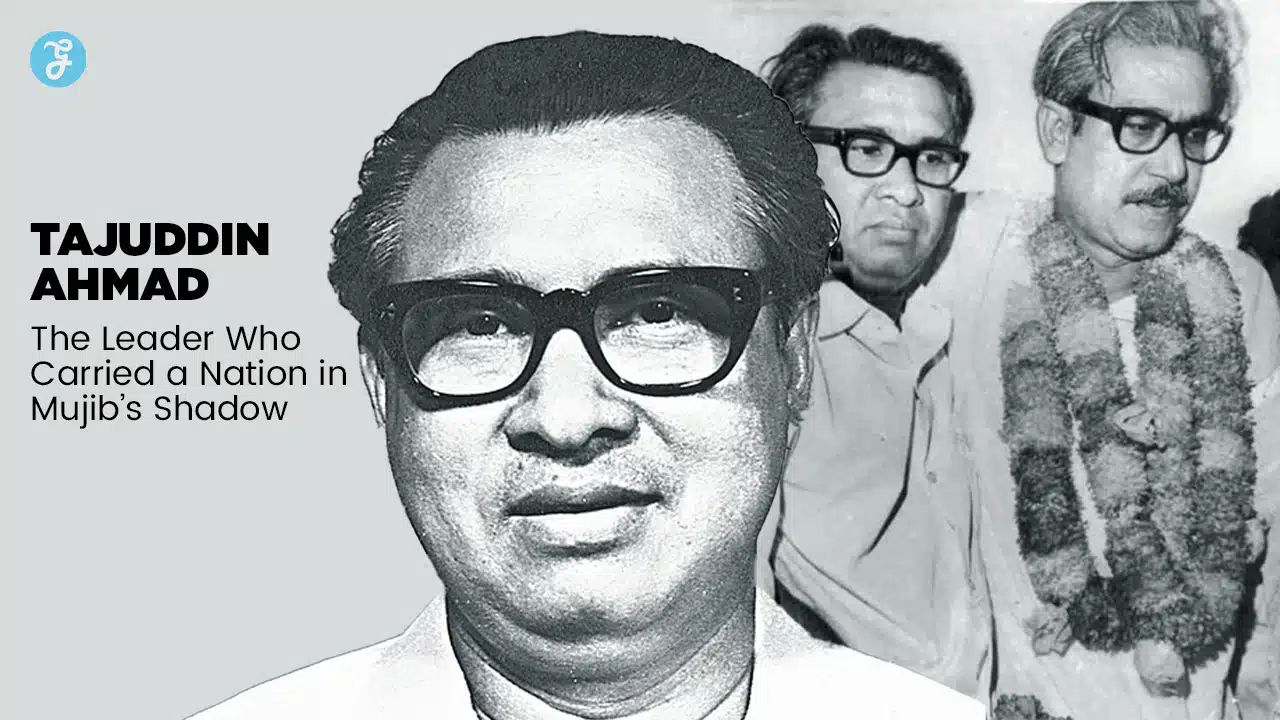

In the grand tapestry of Bangladesh’s liberation, one name so often echoed is Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Yet in the shadows of his towering presence stood a leader equally critical—Tajuddin Ahmad.

As the architect of the wartime Mujibnagar Government, the chief strategist of the Liberation War, and the moral compass of a young nation, Tajuddin remains one of history’s most underappreciated heroes.

This editorial revisits his sacrifices, leadership, and unwavering devotion to Bangladesh.

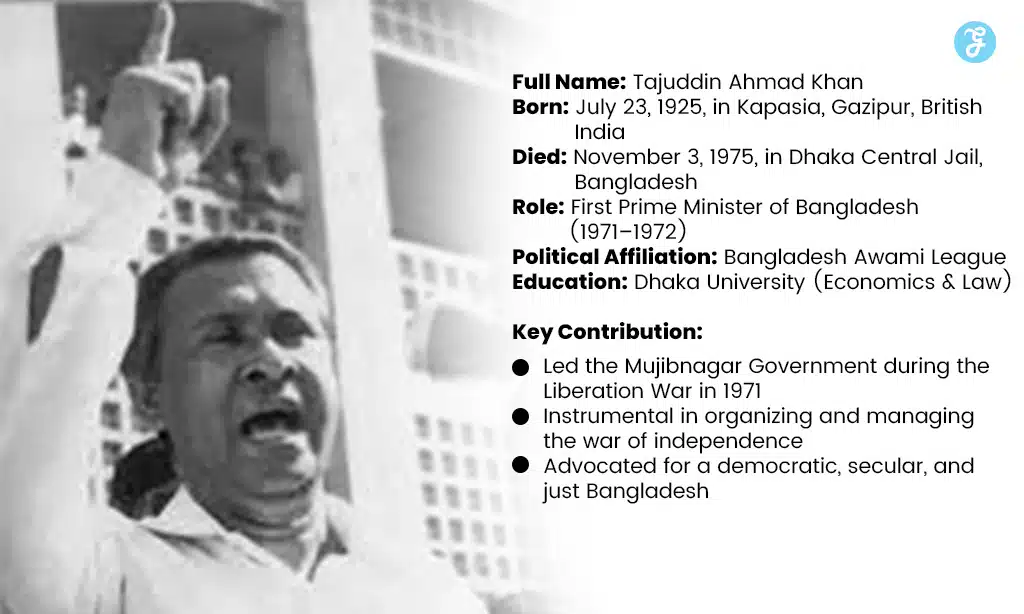

Tajuddin Ahmad at a Glance

Born in Kapasia, Gazipur, on July 23, 1925, Tajuddin’s political journey began in the 1940s with the Muslim League youth wing. He played a significant role in the 1952 Bengali Language Movement and helped draft the iconic “six-point” demand in 1966, which became the signature charter of East Pakistan’s autonomy.

As Awami League General Secretary from 1966, he breathed life into the party, articulated its vision, and was imprisoned multiple times fighting dictatorship.

As a chief organizer during the 1970 electoral victory and the subsequent non-cooperation movement, his strategic planning, diplomacy, and dialogue with Yahya Khan showcased his frontline leadership

Tajuddin Ahmad: The Man Who Walked Alone

Tajuddin Ahmad was not a man of pomp or power. When he severed familial ties and plunged into the flames of war, he asked for no reward. What he received instead was silence, blame, and eventual betrayal.

In life, he bore solitude; in death, near-erasure. And yet, it was this very solitude that gave birth to his clarity, his courage, and his legendary patriotism.

In a nation dazzled by artificial lights of power and praise, the warmth of Tajuddin’s natural leadership became harder to appreciate. Much like how the electric bulb casts shadows in windowless buildings, so too did political artificiality eclipse the genuine radiance of Tajuddin’s sacrifice.

Bangabandhu and the Turmoil of March 25, 1971

On the night of March 25, 1971, as Pakistani tanks rolled into Dhaka, a critical decision awaited Bangabandhu. Tajuddin had drafted a short declaration of independence and urged Mujib to record it.

But Bangabandhu hesitated, fearing charges of treason. Tajuddin, disillusioned, left House 32 in quiet despair and began what would become a lone yet defining journey.

This moment, though sensitive, speaks volumes about Tajuddin’s clarity and courage and Bangabandhu’s caution. The complexities of leadership in wartime were already on full display.

Tajuddin’s Silent Exit and First Step Toward War

Without bidding farewell to his family, Tajuddin departed with Barrister Amir-ul Islam and Dr. Kamal Hossain. Three days later, he sent a note to his wife urging her to “blend into the 75 million,” suggesting he might never return.

With no formal authority and little guidance, he moved toward the Indian border, where history would unfold through his courage. His journey was not just geographical but symbolic—he was moving from the private into the public, from emotion into revolution.

Forming the Mujibnagar Government

Tajuddin built the Mujibnagar Government-in-Exile in April 1971, assuming the role of Prime Minister. From diplomacy to warfare logistics, he shouldered the burden of an unborn nation.

He secured global sympathy, oversaw the training of the Muktibahini (freedom fighters), and gained critical support from India and the Soviet Union.

His negotiation skills ensured India’s open military and diplomatic support. Through the Indo-Soviet Treaty signed on August 9, 1971, Tajuddin secured a geopolitical buffer against American and Chinese influence favoring Pakistan.

Internal Conflicts and Unshaken Resolve

Tajuddin’s mission wasn’t without friction. Young Awami League leader Sheikh Fazlul Haque Moni resisted his leadership. Even among allies, ideological differences—such as over forming the National Liberation Front—threatened cohesion. Yet Tajuddin pressed on, driven by vision, not vanity.

He made all members of the provisional government pledge to forgo family life until independence was won. He honored this vow personally, enduring emotional pain in silence.

Diplomacy that Altered the War

Tajuddin’s deft handling of the Indo-Soviet Treaty in August 1971 was a masterstroke. This alliance neutralized U.S. and Chinese pressure, paving the way for Indian military intervention.

Under his coordination, the liberation forces gained access to weapons, strategy, and crucial international legitimacy.

His dialogue with Indira Gandhi and involvement of leftist leaders like Comrade Moni Singh helped mobilize Soviet sympathy for Bangladesh’s cause.

Post-Liberation Contributions

After victory, Tajuddin refused to bask in glory. As finance minister, he focused on reconstruction, nationalization, and resisting foreign aid with strings attached.

He drafted the 1972 Constitution, incorporating secularism, nationalism, socialism, and democracy—the ideological DNA of Bangladesh.

His economic vision emphasized self-reliance, accountability, and ethical governance.

Bangabandhu’s Return and Political Rift

Despite his wartime leadership, Tajuddin was gradually sidelined. Bangabandhu never inquired how the nation had been run in his absence. By 1974, political rifts widened. Tajuddin resigned from the cabinet, disillusioned by the growing sycophancy and foreign policy shifts toward the U.S. and OIC.

He said, tearfully, “I never thought of myself. I saw Bangladesh through Bangabandhu.”

Warning Ignored, Betrayal Ensued

In July 1975, Tajuddin warned Bangabandhu about a looming military conspiracy. His warnings were dismissed. On August 15, Bangabandhu was assassinated. Tajuddin, devastated, lamented that had he been in the cabinet, the tragedy might have been averted.

Jail Killing: The Silent Assassination of the Nation’s Conscience

Arrested shortly after Mujib’s death, Tajuddin foresaw his fate. “Think of this as me leaving forever,” he told his family. On November 3, 1975, he and three other national leaders were butchered inside Dhaka Central Jail. The nation lost not just leaders but moral anchors.

These killings erased the most capable custodians of the Liberation War’s ideals.

Tajuddin’s Political Philosophy

- Secularism: Advocated for a non-communal Bangladesh rooted in equality.

- Self-Reliance: Opposed aid with conditions, championed economic justice.

- Truth over Power: Preferred ideals over political gain.

- Youth Engagement: “Talk less, act more” was his call to action.

- Institution over Personality: Believed institutions—not individuals—must carry democracy.

Legacy and Lessons of Tajuddin Ahmad

Tajuddin’s story is one of silent, sacrificial leadership. His daughter Simin Hossain Rimi rightly said, “He died like he lived—honest, uncorrupted, and unbending.” Yet textbooks omit him, and national tributes bypass his name. His wartime diaries, if ever found, may yet rewrite official history.

Despite ideological differences, Tajuddin never betrayed Bangabandhu. But Bangabandhu, surrounded by flatterers like Khandaker Mushtaq, failed to appreciate Tajuddin’s worth in time.

The Missing Chapter of Our National History

Even 50 years later, Bangladesh struggles to teach children the truth of Tajuddin’s sacrifice. He wasn’t just a supporting actor. He was the director of the wartime drama.

Without his intellect and initiative, the Liberation War would have lacked coordination, legitimacy, and victory.

Takeaways: A Light That Still Guides

To remember Bangabandhu while forgetting Tajuddin is to tell an incomplete story. If Mujib was the sun, Tajuddin was the moon—reflecting light during Bangladesh’s darkest hours.

His leadership was not loud but luminous. As we commemorate his 100th birth anniversary, let us return to his principles: duty over drama, truth over title.

Let the nation know: in the shadows of Mujib, Tajuddin Ahmad led the Bangalee nation.