Concrete is everywhere. It supports our homes, roads, bridges, hospitals, and schools. But the material that makes concrete possible, cement, is also one of the world’s biggest industrial sources of carbon emissions.

That is why sustainable concrete is getting so much attention. It aims to cut the “embodied carbon” of concrete, meaning the emissions released before a building or bridge is even used. The goal is simple: keep the strength and durability we need, while lowering the climate impact as much as possible.

In this guide, you will learn what makes concrete carbon-intensive, what low-carbon options work today, what is emerging, and how to specify sustainable concrete on real projects without guesswork.

Why Concrete’s Carbon Footprint Is So High

Concrete itself is not the main problem. The biggest carbon hotspot is cement, especially the part called clinker.

Cement Is The Carbon Hotspot (Clinker + Calcination + Heat)

Most concrete emissions come from making cement. Cement is produced by heating limestone and other materials in a kiln at very high temperatures. That creates two major sources of CO₂:

- Chemical emissions (process emissions): When limestone is heated, it releases CO₂ as it turns into lime. This is called calcination.

- Fuel emissions (energy emissions): Kilns need intense heat, often produced by burning fossil fuels.

This is why reducing cement, or replacing some of it, is often the fastest path to lower-carbon concrete.

“Embodied Carbon” vs Operational Carbon (And What This Article Covers)

There are two main carbon buckets in construction:

- Embodied carbon: Emissions from materials and construction, including cement production, transport, and installation.

- Operational carbon: Emissions from running a building over time, like heating, cooling, and electricity.

This article focuses on embodied carbon. For many new buildings, embodied carbon is a large share of total lifetime emissions, especially as operational energy becomes cleaner.

What Sustainable (Low-Carbon) Concrete Actually Means

“Sustainable concrete” can mean different things in marketing. In practice, it should mean lower emissions that can be measured and verified.

A Practical Definition (Lower GWP, Same Performance)

A practical definition is this:

Sustainable concrete is concrete with lower embodied carbon, usually measured as lower Global Warming Potential (GWP), that still meets the project’s performance needs for strength, durability, and constructability.

A strong claim needs proof. The best proof comes from environmental documentation like EPDs, which you will learn about later.

The Three Levers That Usually Matter Most

Most real-world strategies fall into three levers:

Reduce cement and clinker content

- Replace a portion of cement with supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs)

- Use blended cements that include limestone or other components

- Optimize mix design so you do not use more cement than needed

Improve mix efficiency

- Specify the right strength for the job

- Avoid overdesign by default

- Use admixtures and better grading to reduce cement demand

Use carbon-reducing processes

- Carbon curing or mineralization in some products

- Carbon capture at cement plants over time

- New cement chemistries in select cases

If you remember one thing, remember this: most carbon savings come from cutting clinker and cement, not from small tweaks.

The Best-Proven Options Available Today (What Works Now)

This section covers the solutions you can use now, at scale, in many regions. The best option depends on project type, climate exposure, schedule, and local supply.

SCMs (Fly Ash, Slag, Silica Fume, Natural Pozzolans)

SCMs are materials that partially replace Portland cement in concrete. They can lower carbon because they reduce the amount of clinker-based cement needed to achieve strength and durability.

Common SCMs include:

- Fly ash: a byproduct from coal power plants

- Slag cement (GGBFS): a byproduct from steel production

- Silica fume: a very fine byproduct used for high performance mixes

- Natural pozzolans: volcanic ash and similar materials

- Calcined clays: processed clays that can behave like pozzolans

Typical benefits

- Lower embodied carbon by reducing cement

- Improved durability in many cases, especially against chlorides and sulfates

- Lower heat of hydration, helpful for mass concrete

Common tradeoffs

- Slower early strength gain in some mixes

- Different finishing behavior on slabs

- Quality and supply can vary by region

- Needs good curing, especially in dry or cold conditions

Practical tip: If schedule is tight, ask for trial mixes that target early strength milestones. You can often get both lower carbon and reliable early strength by balancing SCM type, cement type, and admixtures.

PLC (Portland Limestone Cement) And Other Blended Cements

Portland Limestone Cement, often called PLC, replaces a portion of clinker with finely ground limestone. Many teams like PLC because it can be a lower-carbon “drop-in” option with minimal change to construction practice.

Why it helps

- Less clinker per ton of cement means fewer emissions

- Often available through normal cement supply chains

What to watch

- Confirm local standards and acceptance

- Review mix performance with your ready-mix supplier

- Keep curing practices strong, especially for flatwork

For many projects, switching to PLC plus a moderate SCM replacement is one of the easiest ways to reduce embodied carbon without major risk.

LC3 / Calcined Clay Pathways (Scaling Beyond Fly Ash/Slag Limits)

In some regions, fly ash and slag supplies are tightening due to changes in energy and steel industries. That increases interest in alternatives like calcined clay systems, including LC3 style blends.

Why this matters

- Clays are widely available in many parts of the world

- Calcined clays can replace a meaningful portion of clinker

- They can support scalable low-carbon cement production

What to watch

- Availability is still uneven in many markets

- Some blends require careful control of water demand and workability

- Specifications may need updating to allow performance-based acceptance

If your region has limited fly ash or slag, this pathway may become more important over the next few years.

Recycled Aggregates And Circular Concrete (Where It Makes Sense)

Aggregates are the sand and stone in concrete. Recycled aggregate is often made by crushing old concrete.

This option can help sustainability, especially by reducing waste and raw material extraction. Carbon benefits vary, because aggregates generally contribute less CO₂ than cement.

Best-fit use cases

- Non-structural applications

- Road base and subbase

- Some structural concrete where quality control is strong and codes allow

Key risks

- Higher water absorption, which can affect workability

- Variability in quality if not well processed

- Potential impacts on strength and durability depending on replacement rate

Practical tip: Start with partial replacement and require clear testing data for absorption, gradation, and strength performance.

Carbon Curing / Mineralization (What It Does And Doesn’t Do)

Carbon curing systems inject or expose concrete to CO₂ so that some of it becomes locked into mineral forms. This can lower net emissions in certain products and plants, especially in precast or controlled settings.

What it can do

- Improve strength in some cases, allowing lower cement content

- Store a measured amount of CO₂ in concrete

What it cannot do

- It usually does not “erase” the cement footprint

- Savings vary widely by process, product type, and mix design

- Claims should be verified with product-specific documentation

Treat this as a tool, not a magic fix. Sustainable concrete is still mostly about lowering clinker and cement.

Options, Use Cases, Tradeoffs, And Verification

| Option | How It Cuts CO₂ | Best Use Cases | Key Tradeoffs | How To Verify |

| SCMs (fly ash, slag, pozzolans) | Replaces cement, reduces clinker | Structural concrete, slabs, infrastructure | Early strength, finishing, supply variability | Mix submittals, EPDs, trial batches |

| PLC / blended cements | Less clinker in cement | Broad use, easy substitution | Must confirm compatibility and acceptance | Cement type documentation, EPDs |

| Calcined clay / LC3-style blends | Reduces clinker with clay systems | Regions with limited fly ash/slag | Availability, spec acceptance | Supplier data, EPDs, performance testing |

| Recycled aggregates | Reduces virgin aggregate demand | Base layers, some concrete mixes | Absorption, quality variability | Aggregate testing, mix performance |

| Carbon curing/mineralization | Stores CO₂ and may cut cement need | Precast, controlled production | Savings vary, needs documentation | Product-specific EPDs, supplier reporting |

At this point in many projects, the best near-term recipe for sustainable concrete is a smart combination of blended cement plus SCMs, verified with EPDs and confirmed through trial mixes.

Emerging Solutions (High Potential, Still Scaling)

Some solutions can deliver deeper reductions, but they often face scaling, specification, or supply challenges.

Geopolymer And Alkali-Activated Concretes

Geopolymer and alkali-activated concretes can reduce emissions by using alternative binders instead of traditional Portland cement.

Why they are promising

- Can significantly reduce clinker use

- Can achieve high strength and chemical resistance in some formulations

Main challenges

- Limited standardization in many markets

- Specifiers may not have established acceptance pathways

- Requires careful handling and quality control

- Material availability and consistency can vary

Where they show up today

- Specialty infrastructure applications

- Precast products in some regions

- Pilot projects with strong technical support

If you consider this option, plan for extra coordination with engineers, suppliers, and local authorities.

Cement Plant Carbon Capture, Utilization, And Storage (CCUS)

CCUS aims to capture CO₂ from cement production and store it or use it elsewhere. This targets the hard-to-avoid process emissions from calcination.

Why it matters

- Cement has a large share of emissions that are chemical, not just fuel-based

- Deep decarbonization likely needs capture technologies in many scenarios

Reality check

- It is capital-intensive

- It depends on infrastructure, policy, and long-term economics

- Adoption is growing, but not universal

For many projects today, CCUS is not something you specify directly. It is more of an upstream supply chain shift that may show up in future EPD improvements.

Novel Cements And Alternative Feedstocks

Researchers and companies are exploring new cement chemistries, alternative raw materials, and new kiln approaches.

Common themes include:

- Lower-temperature processes

- Different mineral systems that emit less CO₂

- Industrial byproducts as inputs

Some of these may become mainstream over time, but availability and standards are still developing in many areas.

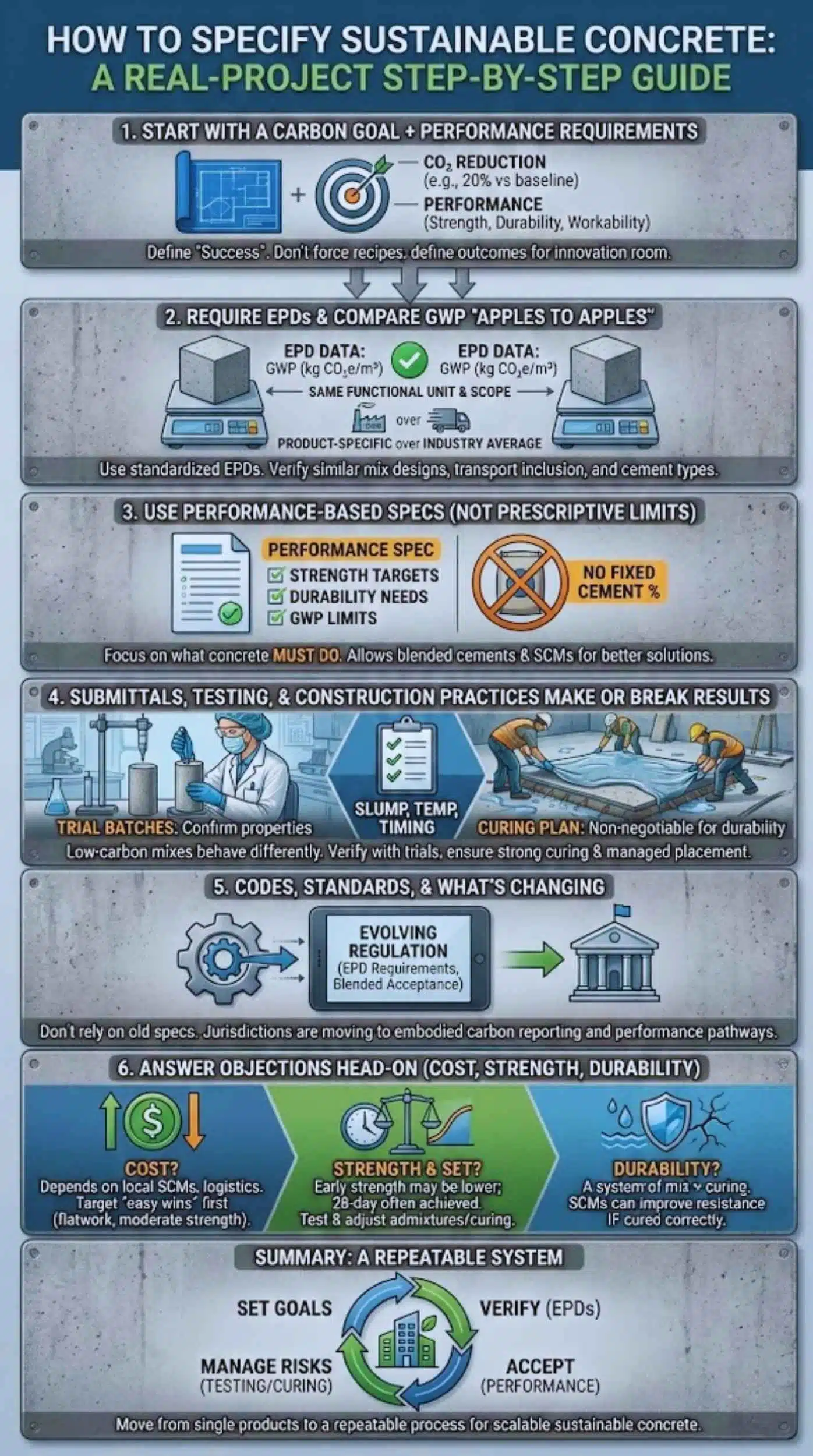

How To Specify Sustainable Concrete (Step-By-Step For Real Projects)

This section is for people who need to buy concrete, not just read about it. If you are an architect, engineer, contractor, developer, or public agency, these steps will help you reduce carbon while protecting quality and schedule.

Start With A Carbon Goal (Budget Or % Reduction) + Performance Requirements

Start by defining what “success” means. You need both a carbon target and performance requirements.

Carbon target examples

- “Reduce concrete embodied carbon by 20 percent vs baseline mixes”

- “Meet a maximum GWP limit per cubic meter for each strength class”

- “Use the lowest GWP mix that meets performance and schedule needs”

Performance requirements to lock in

- Strength at required ages (often 7, 28, or 56 days)

- Durability needs based on exposure (chlorides, sulfates, freeze-thaw)

- Workability and finish requirements for slabs

- Thermal and cracking requirements for mass pours

- Setting and curing expectations tied to schedule

Tip: Avoid forcing a single recipe like “use X percent fly ash.” Instead, define outcomes. This gives suppliers room to innovate.

Require EPDs And Compare GWP “Apples To Apples”

An Environmental Product Declaration (EPD) is a standardized document that reports environmental impacts, including GWP.

To use EPDs well, you need comparison rules.

EPD basics

- Prefer product-specific EPDs tied to a plant and mix

- Confirm the same functional unit and system boundaries

- Check whether transport is included or excluded

- Compare mixes designed for the same strength and performance

Common mistakes

- Comparing a product-specific EPD to an industry average without noting the difference

- Comparing mixes with different performance levels

- Ignoring the impact of cement type and SCM percentage

Actionable approach: Create a simple EPD submittal requirement:

- Submit mix design and EPD for each proposed mix

- Report GWP per cubic meter (or local unit)

- Report strength class and intended exposure conditions

- Confirm compliance with performance requirements

- Provide trial batch results if required

This helps you verify real reductions instead of relying on marketing language.

Use Performance-Based Specs (Not Prescriptive Cement Limits)

Performance-based specifications focus on what the concrete must do, not exactly what it must contain.

This approach is often better for low-carbon goals because:

- It allows blended cements and alternative SCM options

- It supports regional differences in supply

- It reduces the risk of disqualifying better solutions

What to include in a performance-based low-carbon spec

- Strength targets and test ages

- Durability requirements for exposure conditions

- Maximum shrinkage or cracking controls if needed

- Maximum GWP limits, or a required reduction vs baseline

- Documentation rules for EPDs and submittals

If your organization is new to this, start with one concrete category first, like slabs or non-critical structural elements, then expand.

Submittals, Testing, And Construction Practices That Make Or Break Results

Even the best mix design can fail if construction practices are weak. Low-carbon mixes may behave differently, especially with higher SCM content.

Key practices

- Trial batches: Confirm workability, finish, set, and strength development

- Curing plan: Strong curing is non-negotiable for durability and strength

- Placement and consolidation: Avoid re-tempering with water on site

- Finishing timing: Some mixes have different bleed rates and set times

- Cold and hot weather planning: Adjust admixtures and curing methods

Simple risk-control checklist for contractors

- Confirm target slump and slump retention

- Confirm allowed water additions and how they are tracked

- Confirm curing method and duration

- Confirm testing schedule and acceptance criteria

- Confirm backup plan if early strength is slower than expected

Codes, Standards, And What’s Changing

Standards and codes are evolving. Many jurisdictions and industry bodies are moving toward:

- Better embodied carbon reporting

- More acceptance pathways for blended cements

- Performance-based approaches for low-carbon concrete

- Public procurement rules that require EPDs or carbon limits

Practical takeaway: do not assume yesterday’s default spec is future-proof. If you want sustainable concrete at scale, your specs and procurement language may need updates.

At around this point in the process, using sustainable concrete becomes less about a single product and more about a repeatable system: set goals, verify with EPDs, accept through performance, and manage risks through testing and curing.

Cost, Strength, Durability, And Risk (Answer The Objections Head-On)

Teams often hesitate because they fear cost increases, lower strength, slower schedules, or durability problems. Most of these risks can be managed with good planning.

Does Low-Carbon Concrete Cost More?

Sometimes yes, sometimes no. Cost depends on:

- Local availability of SCMs and blended cements

- Cement pricing and supply constraints

- Admixture needs to meet set time and strength targets

- Project logistics, like pumping distances and placing conditions

- Testing and trial batch requirements

Where cost can stay flat

- When a supplier already stocks blended cements and SCMs

- When performance-based specs allow optimization

- When carbon targets avoid extreme mix changes in high-risk pours

Smart cost strategy

Start by targeting “easy wins” first:

- Flatwork mixes where high early strength is not critical

- Moderate strength classes with flexible schedules

- Non-architectural elements where finishing needs are simpler

Strength And Set Time: What Usually Changes

Low-carbon mixes often change the early-age behavior of concrete.

Common patterns

- Early strength at 1 to 3 days may be lower with high SCM content

- 28-day strength is often achievable, and later strength may be equal or higher

- Set time can shift depending on SCM type, temperature, and admixtures

How to manage it

- Specify strength at multiple ages if schedule depends on it

- Use trial mixes to tune admixture packages

- Adjust curing and protection plans for temperature and moisture

- Consider longer curing windows where possible

If your schedule is tight, do not guess. Test early.

Durability Concerns (Freeze–Thaw, Sulfates, Chlorides, Carbonation)

Durability is not just a material choice. It is a system of mix design, curing, placement, and exposure conditions.

Key durability drivers

- Water-to-binder ratio

- Air entrainment for freeze-thaw regions

- Permeability and pore structure

- Proper curing to reduce surface weakness

- Protection against aggressive chemicals

Important note

Some SCMs improve resistance to chlorides and sulfates. But poor curing, poor finishing, or excess water on site can destroy those benefits.

Sustainable concrete is not automatically more durable. It can be, but only when designed and executed correctly.

Real-World Use Cases (Where Sustainable Concrete Delivers Fast Wins)

Different concrete elements have different performance risks. That makes some areas better starting points than others.

Buildings (Slabs, Foundations, Cores)

Good starting points

- Slabs-on-grade and many interior slabs

- Foundations where early strength is not extremely time-sensitive

- Vertical elements with good curing control

Example

A mid-rise building team might reduce embodied carbon by:

- Using PLC as the default cement

- Replacing 25 to 40 percent of cement with slag or fly ash where feasible

- Requiring EPDs and selecting the lowest GWP mix that meets strength and finish needs

Infrastructure (Roads, Bridges, Sidewalks)

Infrastructure can be a strong fit because durability often matters more than fast early strength, and agencies can set clear procurement rules.

High-impact opportunities

- Pavements and sidewalks

- Bridge decks with chloride exposure control

- Barriers and retaining walls

Example

A city sidewalk program might:

- Standardize a low-carbon mix for most pours

- Use a stricter curing requirement to protect long-term performance

- Track embodied carbon savings per year as a public reporting metric

Precast And Masonry Products (Where Carbon Curing Often Fits)

Precast products are made in controlled environments. That can improve consistency and make it easier to adopt new processes.

Where this helps

- Precast panels and structural elements

- Blocks, pavers, and smaller components

- Products that can benefit from controlled curing, including carbon curing methods

Example

A precast plant might reduce cement content due to strength gains from optimized curing, then verify the change with product-specific EPDs.

Sustainable Concrete Checklist (Printable Summary)

Use this quick checklist to move from intention to execution:

- Define a concrete embodied carbon goal (baseline and target)

- Decide whether limits are % reduction or maximum GWP thresholds

- Require EPDs for proposed mixes and set comparison rules

- Use performance-based specs to allow innovation

- Select SCMs and blended cements that match local supply

- Run trial batches for workability, set time, finish, and strength

- Lock in curing plans and temperature controls before pours

- Track results: GWP, strength results, and lessons learned for the next project

This is how sustainable concrete becomes repeatable, scalable, and reliable.

Final Thoughts

Concrete is not going away, but its carbon footprint can shrink significantly. The most reliable strategy is to reduce clinker and cement demand through blended cements and SCMs, then verify results with EPDs and confirm performance through testing and strong curing.

If you want a durable, repeatable approach, treat sustainable concrete as a project system: set goals, request verified data, allow performance-based innovation, and manage construction practices tightly. Done well, it can lower embodied carbon without sacrificing safety, strength, or schedule.