In a landmark study that is captivating the global scientific community, researchers have unveiled an entirely new hybrid state of matter — one that exists somewhere between a solid and a liquid. This “intermediate” or “hybrid” state is challenging long-held assumptions about how matter behaves and could transform industries ranging from electronics to quantum computing.

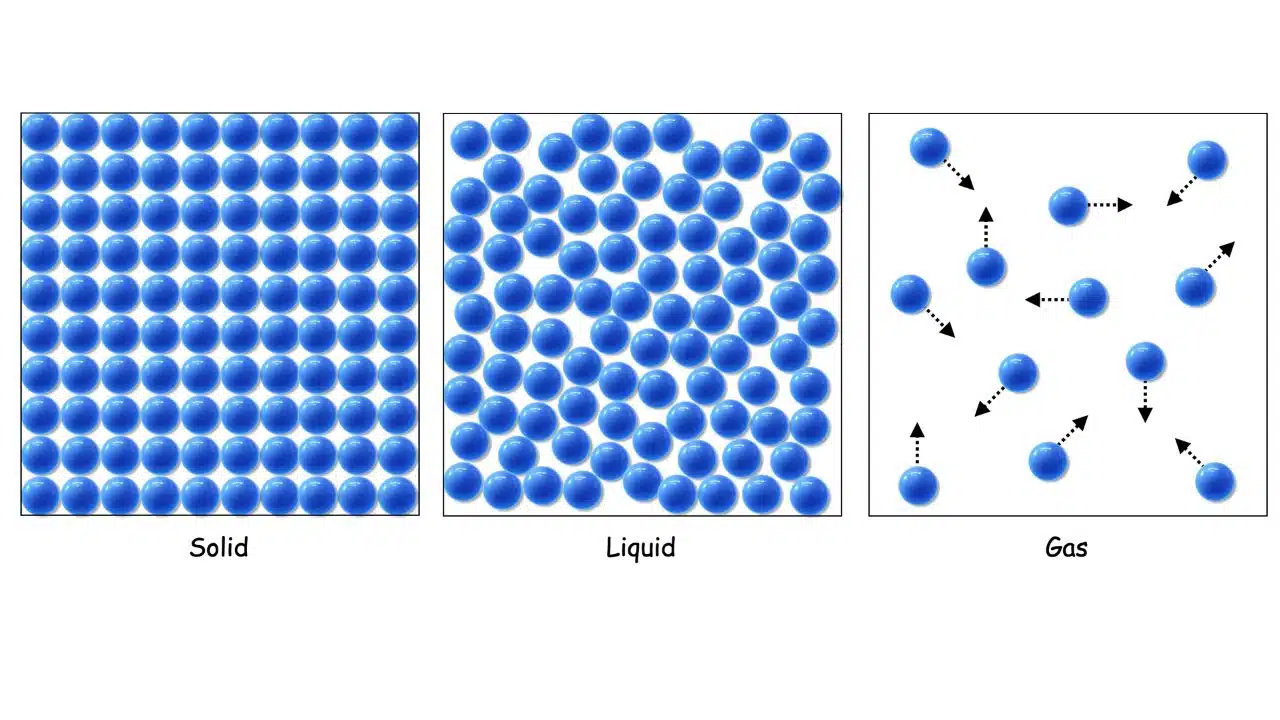

For centuries, scientists have categorized matter into a handful of simple phases: solid, liquid, gas, and, in extreme conditions, plasma and Bose-Einstein condensates. Each category represents a distinct way in which atoms interact and organize. But this new discovery reveals that under specific physical conditions, materials can behave both like a rigid solid and a freely flowing liquid — at the same time.

The Breakthrough: A Material That Defies Categorization

The discovery was made by a multidisciplinary team of physicists and materials scientists at an international research consortium involving MIT, the University of Cambridge, and the Max Planck Institute. Using advanced imaging techniques and atomic simulations, the researchers observed that certain crystalline materials could adopt a mixed state under controlled temperature and pressure ranges.

In this hybrid state, some atomic layers maintain a highly ordered crystal structure — the hallmark of a solid — while adjacent layers move dynamically like a liquid. This atomic choreography allows the material to maintain partial rigidity while also exhibiting flow properties typically seen only in liquids.

According to Dr. Anika Hoffmann, a lead researcher at the Max Planck Institute for the Structure and Dynamics of Matter, this new state “blurs the lines that define classical phases of matter. It’s as if the solid core is wearing a liquid coat — both existing in harmony and influencing one another.”

This level of hybridization had been theorized by physicists for decades but was previously considered nearly impossible to observe directly. Now, thanks to ultra-fast laser spectroscopy and atomically resolved electron microscopy, scientists have proof that this state is not only real but potentially common under certain natural and artificial conditions.

Understanding the Physics: How Solids and Liquids Can Coexist

At the atomic level, solids are characterized by a fixed lattice structure where atoms vibrate around well-defined equilibrium positions. Liquids, by contrast, have no fixed structure — their atoms move freely but remain closely packed.

What the new research reveals is a condition where these two behaviors coexist. Part of the atomic lattice remains orderly, while another part constantly rearranges. The interplay between the static and mobile regions appears to emerge from delicate energy balances between interatomic forces.

This hybrid state can arise in certain materials where the atomic binding energy is just strong enough to maintain local order, but weak enough to allow for dynamic movement in neighboring regions. Temperature and pressure appear to act as key control levers — a slight increase in one or both can induce transitions into this mixed configuration.

Dr. Yujin Lee, a materials physicist at MIT and co-author of the discovery paper, explained: “We found that under specific thermal vibrations, the surface of some crystals begins to melt while the interior remains solid. But instead of fully liquefying, the structure oscillates between these two states at the nanoscale, creating what we now recognize as a hybrid phase.”

Historical Context: Phases of Matter and Their Evolution

The concept of phases — solid, liquid, gas — has been a cornerstone of classical physics since the 19th century. However, more advanced states have been added as science has progressed. The 20th century brought discoveries of plasmas (ionized gases) and Bose-Einstein condensates (superfluid quantum states near absolute zero).

In the 21st century, new quantum and topological phases have expanded this taxonomy even further, revealing exotic properties under conditions never encountered in nature. Yet, this new hybrid solid-liquid phase stands out because it challenges the sharp boundaries between common physical categories.

Historically, scientists assumed transitions between solid and liquid phases were abrupt — once the melting point was crossed, the solid lattice collapsed entirely into a disordered fluid. This discovery shows that nature can take a subtler path: rather than collapsing suddenly, parts of the structure may remain ordered, coexisting with fluid regions in a metastable equilibrium.

Evidence from Computational Modeling and Real-World Observation

The team’s discovery began with theoretical predictions derived from high-performance computational models. Using quantum molecular dynamics simulations, researchers observed behaviors that could not be classified as “pure solid” or “pure liquid.” These simulations revealed regions where particles displayed partial ordering while others flowed past each other.

To confirm the phenomenon experimentally, the scientists created samples of metals and ionic materials cooled and heated under strict conditions while being monitored with femtosecond laser pulses. These ultra-short bursts allowed them to capture real-time snapshots of atomic motion — essentially seeing atoms move at trillionths of a second intervals.

The results were extraordinary. In certain materials such as bismuth telluride and layered oxides, portions of the lattice began oscillating between stable and fluid-like states. The data, verified across multiple laboratories, confirmed that the hybrid state could persist for extended periods before eventually transitioning fully to liquid or reverting to solid.

Dr. Hoffmann described it as “watching matter dance across the phase boundary without choosing a side.”

Implications for Material Science

The implications of this discovery are enormous. Hybrid phases could lead to materials with tunable mechanical or thermal properties, adapting their rigidity or flow based on external stimuli like temperature, pressure, or electromagnetic fields.

Potential applications include:

-

Flexible electronics that can change from rigid to pliable modes without mechanical stress.

-

Thermal regulators capable of dynamically adjusting heat conduction, enabling energy-efficient cooling systems.

-

Smart coatings that can self-heal by temporarily entering a fluid-like state to repair microcracks.

-

Next-generation batteries where hybrid electrolytes combine the ionic conductivity of liquids with the stability of solids.

-

Quantum devices that exploit the coexisting order and fluidity to modulate electron pathways with precision.

According to Dr. Lee, “we are only beginning to scratch the surface of what these materials can do. Once engineers learn to control the conditions that stabilize the hybrid state, we might see a new era of responsive materials — solid enough to maintain structure, yet fluid enough to adapt.”

Nature’s Secret: Where Hybrid States Exist Naturally

Interestingly, nature may already make use of such mixed states. Scientists believe that the interiors of certain planets, including Earth, could harbor hybrid solid-liquid regions under extreme pressure and temperature conditions.

For instance, Earth’s outer core — primarily molten iron — may include crystalline zones maintaining solid lattice frameworks within the fluid environment. Similarly, ice on moons such as Europa may exhibit layer-dependent structures where solid ice coexists with quasi-liquid phases.

Understanding these naturally occurring hybrids could yield insights into planetary evolution, magnetic field generation, and even earthquake dynamics. The hybrid phenomenon might help explain how seismic waves behave differently at various depths or why planetary magnetic fields fluctuate irregularly.

The Thermodynamic Puzzle: Stability and Entropy

To classify this hybrid state formally, scientists must also examine its thermodynamic behavior. Every phase of matter has distinct energy characteristics described by parameters such as enthalpy, entropy, and specific heat capacity. The hybrid phase appears to occupy an unusual niche — its entropy values lie midway between that of solids and liquids, suggesting partial disorder.

Such partial disorder might allow materials to store and release energy more efficiently. In engineering terms, this could enable systems that respond rapidly to temperature changes without suffering structural degradation.

Physicists are developing new mathematical frameworks to define and predict when such intermediate states occur. These models may also reshape the classical phase diagram — the graphical representation of matter’s behavior under varying conditions — to include transitional zones beyond simple linear boundaries.

Engineering Challenges: From Discovery to Application

While the scientific discovery is groundbreaking, practical applications will take time. Stabilizing the hybrid phase outside a laboratory remains one of the biggest challenges. Because these states exist under narrow temperature or pressure ranges, maintaining them in industrial environments requires precise control.

Researchers are experimenting with nanostructures and composite materials that could “trap” the hybrid configuration by design. For example, introducing atomic impurities or layered geometries might anchor the solid regions while allowing controlled mobility in adjacent zones.

Another approach involves applying oscillating electromagnetic fields to sustain partial atomic motion, effectively “freezing” the material in its hybrid form. If successful, this could lead to dynamic systems capable of switching between states on demand — a potential revolution for adaptive engineering.

A Step Toward Understanding Quantum Behavior in Materials

Beyond macroscopic engineering, the discovery also holds theoretical significance for quantum physics. Hybrid solid-liquid phases might serve as useful models for understanding systems with dual order parameters, such as superfluids or superconductors.

In quantum mechanical terms, such materials exhibit overlapping wavefunction behaviors — one favoring order, the other permitting fluidity. This duality could shed light on how correlated electron systems transition between metallic, insulating, and superconducting states.

Some researchers believe that similar hybridization may occur in complex oxides and topological materials known for unusual electrical properties. By linking quantum dynamics to lattice motion, this discovery bridges two powerful domains of modern physics: condensed matter and quantum mechanics.

Expert Reactions: A Redefinition of Matter

The reaction within the scientific community has been both enthusiastic and reflective. Many physicists are calling the discovery one of the most significant additions to the phase landscape in decades.

Dr. Karen Nishida, a theoretical physicist at the University of Tokyo, noted that “this finding redefines what it means for matter to be in a distinct phase. Instead of clear-cut boundaries, we now have evidence of a continuum — a spectrum between solid and liquid behavior.”

Others are emphasizing caution. Some researchers point out that metastable states — temporary configurations that occur during phase transitions — have been observed before, and distinguishing these from truly stable hybrid states requires further evidence. However, the repeatability of these new experiments strongly supports the latter interpretation.

Hybrid Materials and the Future of Technology

Looking forward, hybrid solid-liquid materials could serve as foundational components for future technology ecosystems. In robotics, for instance, soft machines could gain adjustable stiffness for better adaptability. Wearable devices could mold seamlessly to human skin while maintaining durable performance.

In electronics, materials that host both static and dynamic atomic regions might enhance charge mobility while preserving structural stability, improving semiconductor performance. This could also accelerate progress in quantum computing, where coherence and structural order must delicately coexist.

Moreover, in aerospace and energy storage industries, hybrid materials might offer superior shock absorption, radiation resistance, and self-adjusting thermal management — all critical for next-generation systems.

How the Discovery Was Made: A Global Effort

Behind this breakthrough lies an unprecedented international collaboration. The project united experts in materials science, physics, chemistry, and computational modeling. Funding came from multiple institutions, including the European Research Council, the U.S. National Science Foundation, and Japan’s Ministry of Science and Technology.

Researchers combined experimental tools such as atomic force microscopy, synchrotron X-ray diffraction, neutron scattering, and ultrafast laser imaging. This multifaceted approach allowed them to cross-validate results, ensuring both atomic and macroscopic observations aligned.

The project also benefited from machine learning algorithms trained to detect anomalies in atomic data streams, accelerating the identification of hybrid behaviors. This collaboration demonstrates how scientific discovery increasingly depends on global data integration and cross-disciplinary teamwork.

Educational and Philosophical Perspectives

Beyond the technical implications, the hybrid state discovery invites deeper philosophical questions: What does it truly mean for something to “be” a solid or a liquid? At what point does order yield to chaos — and can both coexist indefinitely?

For educators, this represents a valuable opportunity to update how students are taught about phases of matter. Textbooks may soon include hybrid or intermediate categories, emphasizing continuous transitions rather than strict separations.

Dr. Hoffmann summarized it eloquently during a press conference: “Nature doesn’t think in boxes. Our classifications serve convenience, but the universe often prefers complexity over clarity.”

Environmental and Industrial Applications

Environmental scientists are particularly intrigued by the potential sustainability benefits of hybrid materials. Because these substances can change behavior based on external conditions, they could be harnessed for passive climate control — surfaces that adjust their reflectivity or conductivity as temperatures shift.

In industrial contexts, materials capable of partial flow without losing structural integrity could revolutionize manufacturing techniques. 3D printing, for instance, could use hybrid materials that deposit as fluids and solidify selectively during assembly, enhancing precision and reducing energy consumption.

Hybrid electrolytes also promise safer, more durable batteries. By combining the flexibility of liquids and the stability of solids, such systems could minimize leakage, resist degradation, and extend operational lifetimes.

The Path Ahead: Mapping the Unknown

Scientists now face the task of mapping this new terrain — identifying which materials exhibit hybrid behavior, defining its boundaries, and understanding its long-term stability. Large-scale research programs are already forming to explore possible manifestations in metals, ceramics, polymers, and biological compounds.

The next few years may see new alloys or metamaterials explicitly designed to exploit hybrid dynamics. The discovery opens a new branch of material science: hybrid-phase engineering, where the goal is not to choose between solid and liquid properties but to integrate both in one functional framework.

Like the discovery of superconductivity or graphene, this hybrid state could mark the beginning of a new industrial revolution grounded in atomic innovation.

A New Frontier in Material Science

The discovery of a hybrid state where solids meet liquids isn’t just a technical milestone — it’s a paradigm shift in how humanity understands the physical world. It reminds scientists and engineers alike that nature’s complexity often exceeds human categories.

As the research advances, the implications could ripple across physics, chemistry, engineering, and beyond. Hybrid matter holds the promise of reshaping not only the materials we use but the very boundaries that define what matter can be.

Dr. Hoffmann concluded, “We’re witnessing the birth of a new chapter in material science. The line between solid and liquid isn’t a line anymore — it’s a beautiful, dynamic frontier.”