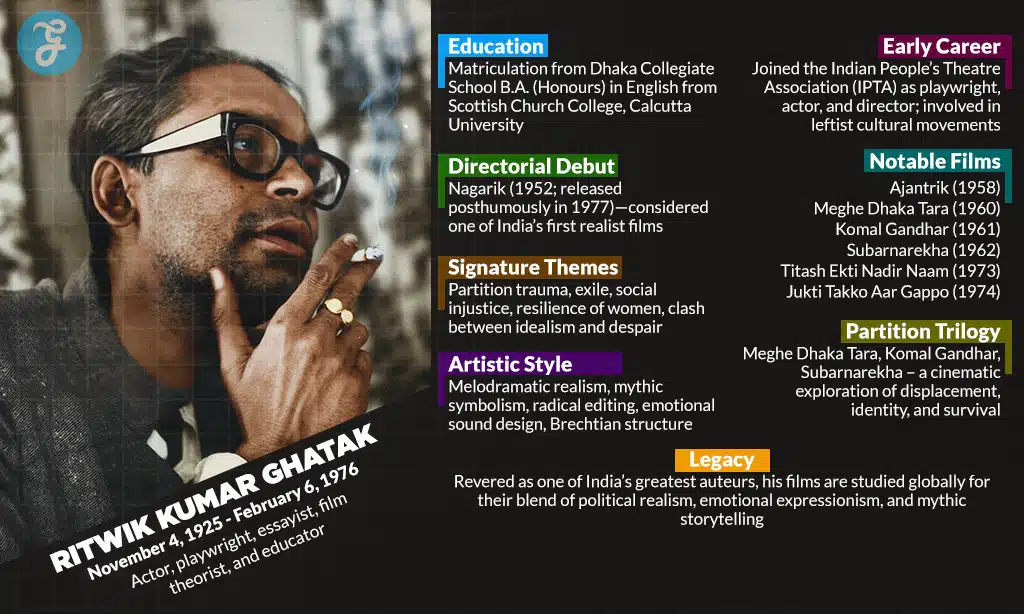

Today marks the 100th birth anniversary of Ritwik Ghatak, a legend of the Bengali film industry whose vision reshaped the language of Indian cinema. Known simply as “Ritwik Ghatak”—a name that evokes both artistry and anguish—he was much more than a filmmaker. He was a storyteller, playwright, actor, and philosopher who used the screen to mirror the wounds of a divided nation.

Born on November 4, 1925, in a respected Bengali family on Rishikesh Das Lane in Dhaka, Ghatak was the youngest of eleven children of Suresh Chandra Ghatak and Indubala Devi. His lineage traced back to the scholar-poet Bhatta Narayan, and his upbringing was steeped in literature, music, and intellectual curiosity. From this cultural soil emerged a man who would one day transform personal loss into cinematic poetry—making Partition not just a historical event, but a haunting, human experience.

On the occassion of Ritwik Ghatak at 100 today, this article is a small tribute to the underrated legend of Bengali film industries.

Ritwik Ghatak at a Glance

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Ritwik Kumar Ghatak |

| Commonly Known As | Ritwik Ghatak |

| Date of Birth | November 4, 1925 |

| Place of Birth | Rishikesh Das Lane, Dhaka (then British India, now Bangladesh) |

| Parents | Father: Suresh Chandra Ghatak (Magistrate and poet) Mother: Indubala Devi |

| Family Lineage | Descendant of Bhatta Narayan, the scholar-poet |

| Siblings | Youngest among 11 children |

| Personal Struggles | Battled alcoholism, health issues, and marginalization from mainstream cinema |

| Marriage | Married Surama Ghatak, an actress and theatre personality |

| Children | One son and twin daughters (including Nabarupa Ghatak) |

| Date of Death | February 6, 1976 |

| Place of Death | Calcutta (now Kolkata), India |

| Age at Death | 50 years |

| Posthumous Recognition | Padma Shri (Posthumous, 1978—declined by family in protest of late recognition) Retrospectives at major film festivals worldwide Restored works by National Film Archive of India (NFAI) |

| Legacy | Revered as one of India’s greatest auteurs, his films are studied globally for their blend of political realism, emotional expressionism, and mythic storytelling |

Early Life and Formative Influences

Ritwik was born with the blue blood of the landlord family of his own Shandilya tribe of the Barendra class. But there is not a trace of the landlord’s family in him. He has seen people, he has thought about the struggle of people, and he has cried for the sorrow of the oppressed people, and that is why he got involved in the labor movement as a protestor while he was only an eighth-grade student.

It is worth mentioning that the best successor of Ritwik Ghatak is the eldest daughter of his elder brother, Manish Ghatak, the renowned writer Mahasweta Devi.

His father, Suresh Chandra Ghatak, was once the District Magistrate of Dhaka, and due to his job, they traveled to different parts of the country. After his father retired, he went to Rajshahi and made his home permanently. Their house in Rajshahi has now been renamed as ‘Rajshahi Homoeopathic Medical College and Hospital.’

Ritwik Ghatak spent a large part of his childhood in Rajshahi City. He passed his matriculation from Rajshahi Collegiate School. Later, he moved to his elder brother, Manish Ghatak, in Baharampur. There, he studied at Krishna Narayan College.

The Partition and the Birth of a Filmmaker

During the partition of 1947, Ritwik Ghatak and his family migrated to Kolkata. He started acting while studying at Rajshahi College.

Ritwik Ghatak wrote his first play, ‘Kalo Sayar,’ in 1948. In the same year, he participated in the revivalist play ‘Nabanna.’ In the meantime, he became so attracted to drama that in 1948, despite being admitted to the English literature department at the University of Calcutta, he gave up his studies due to his addiction to this drama.

In 1951, he joined the Bharatiya Gana Natya Sangha (IPTA). During this time, he wrote, acted in, and directed many plays. Notable plays among these plays are – Jhala, Ofisar, Dalil, Sanko, Sei Mey, etc. During this time, several of his written stories and plays were published in newspapers.

As a result of the movement of the Calcutta (now Kolkata) Film Society, the screening of world classics and other good films started in Kolkata in the beginning of 1950. During this time, he studied a lot about films and realized that the biggest tool and most powerful medium to convey one’s views to a large section of the people was ‘film.’ Inspired by this feeling, Ritwik Ghatak entered the world of celluloid frames through Nimai Ghosh’s film ‘Chinnamoool.’ In this film, he simultaneously acted and worked as an assistant director.

The Cinematic Language of Pain and Poetry

Ritwik’s first immortal creation is ‘Nagarik.’ The film ‘Nagarik’ was made under his sole direction in 1952. But the saddest thing is that the film was not released during his lifetime until 1976. The film ‘Nagarik’ is about the complexities of life of the middle-class society, urban suffering, refugee life, unemployment of the young generation, feelings of disappointment and isolation, self-centeredness, the rise and fall of happiness, sorrow and misery, the illness and sorrow of class division, and the atmosphere of people becoming puppets in the hands of the state.

The central character of this film is ‘Ramu.’ The following year, i.e., in 1953, Ritwik Ghatak’s play ‘Dalil’ won the first prize at the All India Bombay Conference of the Gana Natya Sangha.

Then in 1957, Ritwik’s first released film, ‘Ajantrik,’ was made. He gained fame as a successful filmmaker immediately after the film was released.

After that, Ritwik made his ‘trilogy’ about refugees, ‘Meghe Dhaka Tara’ (1960), ‘Komal Gandhar‘ (1961), and ‘Subarnarekha’ (1962). Based on the story of Shaktipada Rajguru, ‘Meghe Dhaka Tara’ is like a path of light in the infinite darkness and a picture of wanting to survive. The same melody—joy of life—has emerged in the film ‘Komal Gandhar.’ There is also a division in the group of plays made about the partition-refugee boys and girls.

One group is in favor of classic plays; the other group wants the stage form of reality. The film uses a fast pace, loud screams, and buffers. These introduced the audience of that time to a new visual grammar. The subject of Subarnarekha was also the story of refugee life.

After the release of ‘Subarnarekha’ in 1965, Ritwik took an eight-year break from films. After the fame of his talent spread, Ritwik Ghatak first worked as a film direction teacher and then as the principal at the world-famous ‘Film and Television Institute of India’ in Pune in 1966.

Beyond the Screen: Ghatak as Teacher and Thinker

It is worth noting that, at the time when he went to Pune, he also worked as a screenwriter for Hindi films in Mumbai. Then in 1972, he came to Bangladesh and made his famous film ‘A River Called Titas,’ based on the famous novel written by Adwaita Mallabarman. It was made as a joint production of India and Bangladesh. This film, taken from Adwaita Mallabarman’s Dhrupad novel, received wide acclaim. The powerful actor of Bangladesh, Prabir Mitra, played an extraordinary role in this film.

Prabir Mitra reminisces about Ritwik Ghatak like this:

“This is a spider, this is a thorn; come here”—he (Ritwik) used to call me by saying all these things. He never called me by my name. He used to say, You come during editing. I have something to talk to you about. I go and stand there. He doesn’t say anything. He is immersed in his work. He doesn’t raise his face. Ritwik-da is gone. I haven’t heard a word from him again.”

After that, Ritwik’s last film, ‘Yukti, Takko Aar Gappo,’ was released in 1974. He took the film’s plot as a pretext for his own life.

Works and Awards of Ritwik Ghatak

| Category | Title / Description | Year of Release / Recognition | Notes & Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature Films (Director) | Nagarik (The Citizen) | 1952 – released 1977 (posthumous) | First realist film on post-Partition youth struggles; predates Pather Panchali. |

| Ajantrik (The Unmechanical) | 1958 | Psychological parable about man’s attachment to a machine; pioneering absurdist cinema. | |

| Bari Theke Paliye (Runaway from Home) | 1958 | Poetic story of a child escaping rural monotony; social satire on urban illusions. | |

| Meghe Dhaka Tara (The Cloud-Capped Star) | 1960 | His most acclaimed film; tragic portrait of refugee woman Nita; part 1 of the Partition Trilogy. | |

| Komal Gandhar (E-Flat) | 1961 | Part 2 of the Trilogy; examines divided theatre groups and divided Bengal. | |

| Subarnarekha (The Golden Line) | 1962 – released 1965 | Part 3 of the Trilogy; explores exile, class, and loss. | |

| Titash Ekti Nadir Naam (A River Called Titash) | 1973 | Epic on life and decay of fishing communities; among the earliest Bengali ethnographic films. | |

| Jukti Takko Aar Gappo (Reason, Debate and a Story) | 1974 | His final and semi-autobiographical film; Ghatak plays the disillusioned intellectual Nilkantha. | |

| Documentaries & Shorts | Buddhadev Bose (Documentation) | 1959 | Tribute to Bengali poet and dramatist Buddhadev Bose. |

| Amar Lenin | 1970 | Political documentary on Lenin’s ideology and relevance in India. | |

| Fear (Bhoy) | 1961 | Experimental short exploring paranoia and oppression. | |

| Screenplays / Scripts | Chinnamul (dir. Nemai Ghosh) | 1950 | Co-writer; story of refugee displacement post-Partition. |

| Bibar (Unrealized Script) | 1965 (est.) | Planned adaptation from Samaresh Basu’s novel; never produced. | |

| Plays & Theatre Work | Dalil (The Document) | 1948 | Stage play under IPTA on Partition refugees. |

| Kalo Sayor (The Dark Wave) | 1949 | Allegorical drama on social upheaval. | |

| Books & Essays | Cinema and I | Written 1958–1974; published posthumously | Collection of essays and reflections on cinema, myth, and social realism. |

| Teaching & Mentorship | Lecturer / Vice Principal, FTII Pune | 1965–1974 | Mentored Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, John Abraham and others; major influence on Indian Parallel Cinema. |

| Awards & Recognitions | Padma Shri (India) — Posthumous Award | 1978 | Declined by family in protest of delayed recognition. |

| Bangladesh Film Archive Centenary Tribute | 2025 (Planned) | Restored screenings and global retrospectives marking Ritwik Ghatak at 100. | |

| Retrospective – International Film Festival of India (Goa) | 1987 and 2025 (revival) | Featured his Partition Trilogy and Jukti Takko Aar Gappo. | |

| Berlin Film Festival Retrospective | 2013 | International acknowledgment of his cinematic innovation. | |

| FTII Golden Jubilee Recognition | 2010 | Honored as one of the institute’s most influential educators. | |

| Posthumous Legacy | Restoration by National Film Archive of India (NFAI) | 2010s | Digital preservation of Meghe Dhaka Tara, Subarnarekha, Titash. |

| Global Academic Reappraisal | 2000–Present | His theories cited in global film studies alongside Eisenstein and Brecht. |

Ritwik Ghatak’s film Argument and Gossip

Ritwik Ghatak writes in his book ‘Nijer Paye Nijer Pathe’ about the film—

“I will push you every moment to convince you that it is not an imaginary story or I have not come to give you cheap pleasure. I will hammer you every moment to convince you that what you are seeing is an imaginary story, but understand my thesis that what I am trying to convey is completely true, I will alienate you every moment to draw attention to it. If you become aware, if you engage in the work of changing the social barriers and corruption outside by watching films, if I can impose my protest on you, then only is my interest as an artist.”

His greatness was not limited to films alone, his infinite love for humanity was. He always dreamed and showed a social system where there would be no exploitative and exploited relations, no class division, no communalism, bigotry, superstition, and lack of culture. To prove the importance of the word manush, with his own heart and his own open call, he was seen actively participating in relief work for Bangladeshi refugees on the streets of Kolkata during the great liberation war of Bangladesh in 1971.

Some conversations about the active participation of innocent refugees of East Bengal and Bangladesh in the relief work at that time:

“Ritwik smiled. He began to speak clearly, “Where is Suchitra (the great heroine of Bengali cinema Suchitra Sen)? There is a war going on now… a heavy unjust war; the world is now divided into two parts, animals and humans, because of the war. And how much blood is flowing in the land of the Padma-Meghna at this moment… At this moment, the young hands and feet of a child are being burned in the fire. The chest of a child’s mother is being torn open by a sharp bayonet. The houses surrounded by the familiar compassion of our ancestors are being burned… Piles of corpses are piled up in the silt of Bengal… Hungry vultures are flying in the blue sky of Bengal. Far below, the water of the river… Bodies in that water… Bodies on the river bank… Bodies on the road… Bodies in the banana groves… Bodies in the yard… Bodies in the well… Bodies inside the house… Bodies outside the house… Bodies, bodies and bodies and bodies and bodies and bodies and bodies and bodies and bodies.

Suchitra opened her bag again and said, “I should have a blanket wrapped in rags in my bag. Wait and see.” Here, take this. Now top it up and eat it. There is a bottle of water in the car. Shall I bring it?

Ritwik took the padra, but did not eat it. Instead, he smiled faintly and stuffed it into his pocket. You are a human being. Suchitra’s voice was filled with amazement and pride!

Suchitra, how many bodies have you seen at once? 100? 200? 300? 400? 500? 600? 700? 800? 900?

Hearing Suchitra’s words, Ritwik smiled faintly. He thought, as a human being, as an artist, does this girl immersed in this exotic art-culture feel the pain inside me? How many bodies has she seen at once?

Suchitra said, I will go to Ritwik then. Saugat is waiting in the office……….

Ritwik will not leave the battlefield!

As Suchitra got into the car, she thought: Ritwik da will never return to the land where these helpless people are burning in the intense heat right now. Ritwik da and his family had come to this shore in 1947. Yet… such a great film director, it is surprising to think that Ritwik Ghatak, who is compared to world-famous filmmakers… How could that man, forgetting to eat and drink, stand on the burning sidewalk and beg for the refugees of East Bengal?

With this thought, two drops of tears rolled down the asphalt road.

What is this called? Love? Patriotism? Whatever this one thing is. Everything exists because it exists. Otherwise, the world would not have survived this long. When would it all end!

Suchitra got into the car and sat down. Then the white ambassador made a mechanical hum and blew away, blowing smoke.”

Ritwik Ghatak at 100: Why His Vision Matters Today?

Today, as we mark Ritwik Ghatak at 100, we remember not only a filmmaker but a fearless truth-teller — a man who never learned the art of polite deception. Ghatak could never express his thoughts in the refined, self-censored tone favored by the so-called “civilized” elite. Whatever he felt, he said it—directly, passionately, and without fear.

He once declared,

“People see films. As long as the opportunity to show films is open, I will make films to show people and to feed my stomach. If tomorrow or ten years later a better medium than cinema comes out and if I am alive ten years later, then I will kick cinema and go there. I have not fallen in love with cinema. I do not love films.”

To some, this sounded arrogant; to others, it revealed the raw honesty of an artist who valued truth above artifice. Critics mocked him — as they do all visionaries — saying, “Will Ritwik ever fall in love with cinema?” They forgot that Bengal has always produced creators who live on intensity, not approval. Ghatak had his share of detractors, but he also had admirers who saw the fire within him. Even Satyajit Ray, his contemporary and sometimes rival, once said that Ritwik carried within him the pain of a true artist.

Yet, it is an undeniable tragedy that Ghatak never received the recognition he deserved during his lifetime. While lesser filmmakers collected trophies, his genius went largely unacknowledged. The Government of India conferred upon him the Padma Shri in 1970 for excellence in film direction, but honors meant little to him. He worked not for medals or applause, but from an inner compulsion — the urgent need to expose truth, question injustice, and heal a wounded civilization. Artists like him are born once in a century; they do not chase glory — they redefine it.

Perhaps our greatest failure as Bangalee lies in not honoring his contribution to the Bangladesh Liberation War on 1971, or recognizing the depth of his commitment to the unity of Bengal’s soul. Many of Bangladesh’s foreign friends have been decorated in recent years, but Ghatak — who poured his spirit into the dream of cultural solidarity — remains largely unacknowledged.

Even today, his vision seems misunderstood by many in our younger generation. The same society that celebrated the cinematic image of a genius like Satyajit Ray often failed to comprehend Ghatak’s restless, revolutionary gaze. The truth is, without voices like his, cinema loses its conscience.

Though time has passed, Ritwik Ghatak’s work endures — alive, urgent, and unbroken. His films continue to teach, to stir, to haunt. For every serious filmmaker and every thinking viewer, his legacy remains an education — not in technique, but in courage. Ghatak may be gone, but his cinema still breathes wherever truth dares to speak without fear.

Final Words

After years of artistic struggle and emotional torment, Ritwik Ghatak eventually lost his mental balance and spent long months under treatment in a psychiatric hospital. Yet even in his most fragile moments, the fire of creation within him never dimmed. On February 6, 1976, at the age of just fifty, this great craftsman of cinema breathed his last in Kolkata, leaving behind a silence that still echoes in every frame he ever shot.

Though he took his eternal vacation from this world, his films remain immortal — living testaments to truth, pain, and poetic resistance. His art was not bound by time or geography; it spoke of humanity itself. Throughout his life, Ghatak fought relentlessly for the cultural unity of the two Bengals — sometimes through activism, more often through the lens of cinema. From Meghe Dhaka Tara to Subarnarekha, his works became bridges between memory and history, emotion and intellect.

Today, as we celebrate the birth centenary of Ritwik Ghatak, his voice continues to call across generations — reminding us that cinema is not merely entertainment, but conscience. He turned suffering into strength, despair into art, and displacement into universal truth. A century later, his vision still stands tall, whispering to every dreamer and filmmaker: “Make films that speak, even if the world refuses to listen.”