Pandit Ravi Shankar taught the world that silence has a sound. In the complex geometry of Indian classical music, that silence is often the pause between two notes—a breathless moment called the khali, where the soul waits for the next vibration. But today, on December 11, the silence feels heavier. It is the echo of a void left behind thirteen years ago when the strings of the maestro finally came to rest.

Ravi Shankar was not just a musician; he was something far rarer: he was a celestial architect. He took the closed, sacred rooms of Indian classical music—previously accessible only to Maharajas and connoisseurs—and built doors and windows that opened to the entire world. In a world deeply divided by geography, culture, and language, he used a gourd, a few strings, and a plectrum (mizrab) to connect civilizations.

As we mark the thirteenth anniversary of his passing today, we don’t just remember a Sitar Maestro; we remember the man who taught the West how to close its eyes and truly listen to the East.

A Life That Began Far from the Global Stage

Pandit Ravi Shankar was born Robindro Shaunkor Chowdhury on 7 April 1920 in Banaras (now Varanasi), into a Bengali family. History often forgets that before he was a sage, he was a dandy.

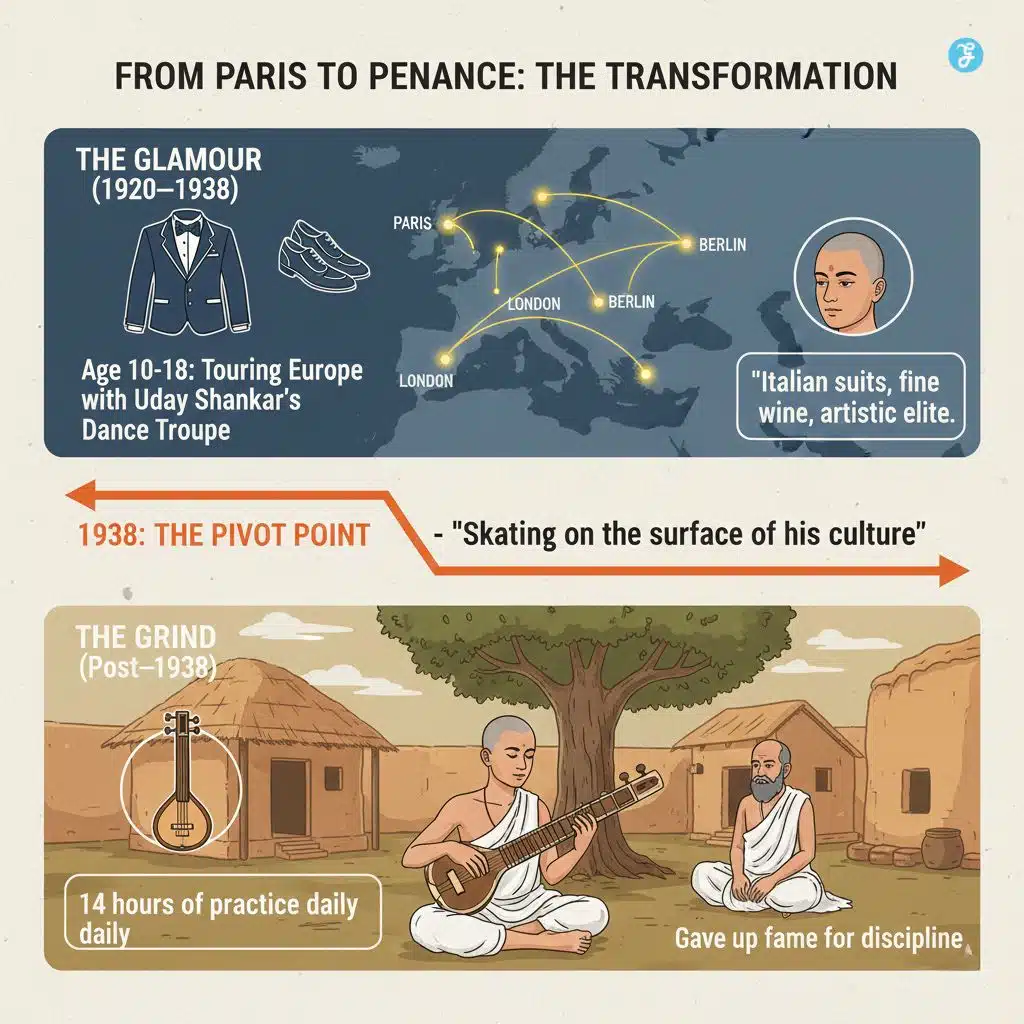

As a child, he didn’t start out with a sitar in his hands. Instead, he was part of his elder brother Uday Shankar’s celebrated dance troupe, touring India and Europe. He wore tailored Italian suits, drank fine wine, and rubbed shoulders with the artistic elite of 1930s Paris. He had fame, comfort, and a clear path to a glamorous life. On those tours, he absorbed not just Indian arts but also Western culture, languages, and audiences.

But in 1938, at the age of 18, a profound emptiness took hold. He realized he was “skating on the surface” of his culture. In a move that defines the hero’s journey, he gave it all up and chose the lonely, disciplined path of a serious musician, returning to India to study the sitar.

Under the Guru’s Eye: Years of Intense Training

Ravi Shankar became a disciple of Ustad Allauddin Khan, one of the greatest gurus of Hindustani classical music. He traded the lights of Paris for the mosquitoes, heat, and dust of Maihar, a small princely state in central India. He shaved his head, donned simple homespun clothes, and surrendered himself to the rigorous, often terrifying discipline of the multi-instrumentalist genius, Baba Allauddin Khan.

This was not just music school; it was a spiritual breaking down. For seven years, Shankar practiced for up to 14 hours a day. It was a feudal, ancient system of learning known as Guru-Shishya Parampara. It was here, in the crucible of isolation, that the “Robindro” of Paris died, and Pandit Ravi Shankar was born. He understood that to take Indian music to the world, he first had to possess it entirely—not just the notes, but the silence between them.

Under Allauddin Khan, he learned:

-

The sitar and surbahar

-

The grammar of ragas

-

Dhrupad, dhamar, khyal, and other classical styles

-

Techniques of instruments such as rudra veena, rubab, and sursingar

By 1939, he was already performing publicly on the sitar, including jugalbandis (duets) with his fellow student and later legendary sarod maestro Ali Akbar Khan. These years forged not just a musician, but an artist with a rare combination of discipline, depth, and imagination.

The Anatomy of Agony: The Sitar Itself

To understand Shankar’s genius, one must understand his tool. The Sitar is not a forgiving instrument. It is a jealous lover that demands physical pain. The strings are made of steel and brass, pulled at high tension. To play them requires cutting a permanent groove into the flesh of the index and middle fingers. Calluses form, peel off, bleed, and form again until the skin turns to leather.

Shankar was not content with the instrument as it was. A restless innovator, he modified the Sitar to suit his vision. While most contemporaries, like the great Vilayat Khan, preferred a lighter, singing tone (Gayaki ang), Shankar craved depth. He added bass strings (kharaj-pancham) to his instrument, giving it a thunderous, resonant growl in the lower octaves.

This allowed him to explore the “Dhrupad” style—serious, spiritual, and ancient. When you hear a Ravi Shankar recording, that deep, vibrating hum that hits you in the chest is his signature innovation; he didn’t just play the melody; he played the atmosphere.

Composer, Broadcaster, Nation Builder

After completing his formal training in the mid-1940s, Pandit Ravi Shankar stepped into a newly independent India that was still defining its cultural voice.

He quickly emerged as more than just a performer. He composed for Satyajit Ray’s iconic Apu Trilogy, helping create one of the most celebrated film scores in world cinema. He served as the Music Director of All India Radio (AIR), New Delhi, from 1949 to 1956, curating and composing music that reached homes across the country.

At AIR, he started the National Orchestra of India, blending Indian instruments and classical styles in new ways. This was Ravi Shankar, the nation-builder—using broadcasting and composition to help shape the sound of a young republic.

The Silent Jazz Revolution: John Coltrane

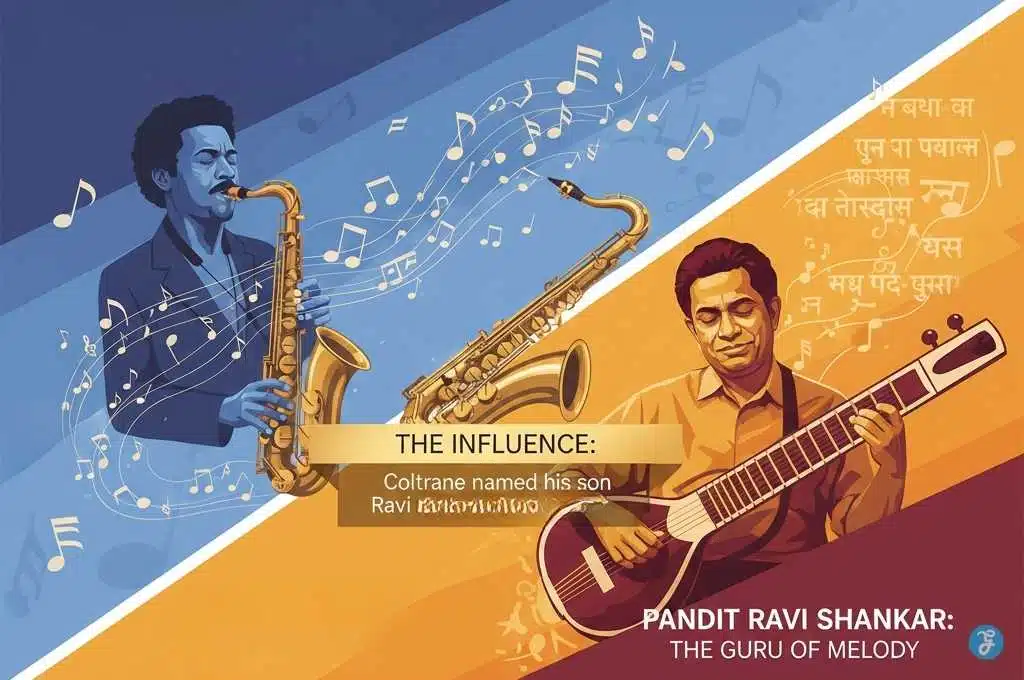

While pop culture associates him with the 1960s “Flower Power” movement, the intellectual West found him much earlier. The jazz community, arguably the most sophisticated musical demographic in America, was the first to bow to him.

In the early 60s, jazz legend John Coltrane found himself at a crossroads. He was looking for a way to break free from Western chord structures. He found his answer in Shankar’s ragas—the concept of improvisation based on a mood rather than a chord change.

Coltrane was so moved by Shankar’s music that he sought him out for lessons in New York. The two masters couldn’t spend much time together, but the impact was seismic. Coltrane began to incorporate Indian circular breathing and modal scales into his playing. The ultimate tribute came not on a record, but on a birth certificate: Coltrane named his own son Ravi Coltrane.

This connection validates Pandit Ravi Shankar not as a “pop influencer,” but as a “musician’s musician.” He altered the DNA of American Jazz before he ever met a Beatle.

The Beatle, The Buffer, and The Backlash

Of course, the explosion happened in 1965. When George Harrison stumbled upon a sitar on the set of Help!, he opened a door that could never be closed. Harrison became Shankar’s student, and suddenly, Indian music was the “sound of the 60s.”

From The Rolling Stones’ Paint It, Black to The Byrds, everyone wanted that droning, psychedelic sound. Shankar found himself performing at the Monterey Pop Festival (1967) and Woodstock (1969).

However, this fame was a double-edged sword. Shankar was a purist. He was horrified by the drug use he saw at these festivals. He famously remarked that the stoned audience at Woodstock reminded him of “water buffaloes in the mud.”

This wasn’t arrogance; it was a desperate plea for respect. He saw the Sitar as a divine instrument, not a background track for an acid trip. He spent the late 60s gently scolding Western audiences, teaching them not to smoke, talk, or make out during a performance. He forced the West to sit up straight and pay attention.

Resonance and Resistance: The Indian Backlash

While he was celebrated as a cultural icon in the West, the story in India was more complicated. As is often the case with pioneers, Pandit Ravi Shankar faced intense criticism at home.

Traditionalists in India accused him of “commercializing” the sacred arts. They claimed he was diluting the Ragas, shortening performances to suit the “short attention spans” of Westerners. They called his music “Export Quality”—a stingingly sarcastic label implying it wasn’t good enough for the connoisseurs back home.

This criticism hurt him deeply. For decades, he had to walk a tightrope—proving his purity in Delhi while championing innovation in New York. History, however, has vindicated him. He didn’t dilute the music; he distilled it. He realized that a Western audience couldn’t sit for a seven-hour concert, so he gave them the essence of the Raga in 20 minutes, without losing its grammatical integrity.

The Shadow of Annapurna Devi

No tribute is honest without acknowledging the shadows. Shankar’s personal life was as complex as his music. His first marriage was to Annapurna Devi, the daughter of his guru and a musician of terrifying brilliance. She played the Surbahar (bass sitar).

Legend and rumors have whispered for decades that their marriage collapsed partly due to professional rivalry—that her playing was so profound it threatened to overshadow his. They separated, and Annapurna Devi became a recluse, vowing never to perform in public again, silencing her music to the world while Shankar’s amplified across the globe.

It is a tragedy of Shakespearean proportions. It reminds us that Pandit Ravi Shankar was a man of immense ambition, and in the pursuit of his global destiny, there were unavoidable collisions.

Diplomacy Through Melody

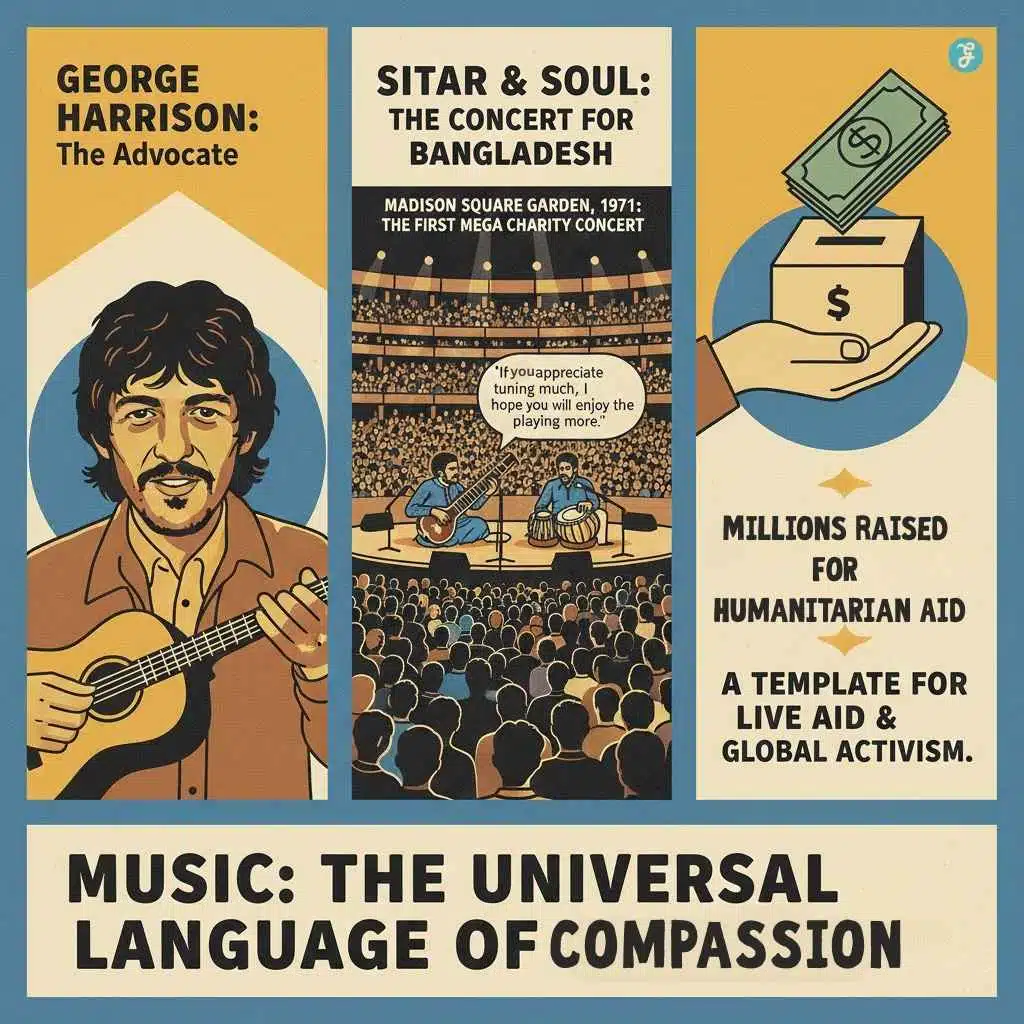

Long before Live Aid or standard charity galas, Shankar invented the concept of the benefit concert.

In 1971, moved by the genocide and refugee crisis in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), he felt he couldn’t just watch the news. He called George Harrison. “I must do something,” he said.

The result was The Concert for Bangladesh at Madison Square Garden. It was the first time music was used on such a scale for humanitarian aid. Shankar opened the show. There is a famous moment where the audience erupts into applause after he and Ali Akbar Khan merely tune their instruments. Shankar, with his trademark wit, leaned into the mic and said:

“If you appreciate the tuning so much, I hope you will enjoy the playing more.”

That concert didn’t just raise millions; it put the plight of a nation on the world map. He proved that a musician could be a statesman.

Beyond Technique: His Philosophy of Music

What made him truly special was not just how he played, but why he played. Across interviews and writings, a few consistent beliefs emerge.

Music, for him, was a spiritual path—a way to touch something beyond the ego and connect with the divine. He often spoke of the need for serious riyaaz, humility, and surrender to the raga, rather than chasing fame or trends.

At the same time, he stayed curious and open. Whether working with Western orchestras, jazz musicians, or rock icons, he wanted genuine dialogue—not shallow fusion or gimmick. This combination of rootedness and openness is perhaps the greatest lesson he leaves for artists today.

The Final Act: Breath and Strings

The most poignant image of his dedication comes from the very end of his life. In November 2012, just weeks before his death, he performed his final concert in Long Beach, California.

He was 92 years old. His body was failing. He required an oxygen mask backstage just to breathe. His daughter, Anoushka, sat by his side, ready to take over if he faltered. But the moment the Sitar was placed in his hands, the years fell away. For that hour, he was not a dying man; he was a conduit for the divine. He played with a vigor that defied medical logic, driven by sheer will and a lifetime of Sadhana (spiritual practice).

Guru, Father, and the Living Legacy

Pandit Ravi Shankar’s legacy is also written in the lives and music of those who followed him. His daughter Anoushka Shankar is today one of the most acclaimed sitar players in the world, building on his tradition while taking the instrument into new compositional spaces and collaborations.

His other daughter, Norah Jones, is a globally celebrated singer-songwriter whose music, though Western in sound, carries the same emotional honesty and subtlety that marked her father’s work.

His many students and disciples, from classical purists to experimental artists, carry forward aspects of his technique, discipline, and philosophy. Even today, younger sitarists and world musicians cite Pandit Ravi Shankar as their inspiration when they blend classical foundations with contemporary sensibilities, whether in fusion projects, film scores, or meditative soundscapes.

Awards, Honors, and a Place in History

Given his impact, it’s no surprise that the list of awards he received is long. A few landmarks:

-

Bharat Ratna (1999) – India’s highest civilian award, recognizing his extraordinary contribution to music and culture.

-

Padma Vibhushan (1981) – the country’s second-highest civilian honor.

-

Three Grammy Awards and several more nominations, including a posthumous Lifetime Achievement Grammy in 2013.

He also served a term in the Rajya Sabha, India’s upper house of Parliament, reflecting the recognition he received as a cultural statesman, not just an artist. But if you read his interviews and watch his interactions, you sense that the true “award” for him was something simpler: the chance to keep playing, keep teaching, and keep sharing.

Why Pandit Ravi Shankar Still Matters Today

In a world full of instant content and background noise, why does Pandit Ravi Shankar still feel so important?

Because he showed that tradition and innovation can coexist. You don’t have to abandon your roots to reach the world. He treated music as a responsibility, not just a career—using it to serve people in need, to build bridges between cultures, to offer solace and reflection.

Also, because of his recordings, whether it’s a deep raga at dawn or an electrifying live performance at Woodstock, they still invite us to sit quietly, close our eyes, and listen with our whole being.

For young musicians, his life is a lesson in patience, depth, and courage. For listeners, he is a reminder that true art doesn’t age; it just finds new ears.

FAQs about Pandit Ravi Shankar

Who was Pandit Ravi Shankar?

A sitar virtuoso, composer, and cultural ambassador who introduced Indian classical music to global audiences.

How did Pandit Ravi Shankar influence Western music?

Through collaborations with artists like George Harrison and Yehudi Menuhin, he brought Indian ragas into Western popular and classical music.

Why is Pandit Ravi Shankar remembered today?

For his pioneering global tours, humanitarian work like the Concert for Bangladesh, and a musical legacy carried forward by artists including Anoushka Shankar and Norah Jones.

Final Words: The Echo in Eternity

Pandit Ravi Shankar passed away on December 11, 2012. But in the truest sense, he never left. His journey began as a boy touring with a dance troupe and ended as a global icon, a Bharat Ratna, a Grammy winner, and above all, a humble servant of music.

The raga he began in 1920 did not end in 2012. It continues every time someone tunes a sitar, puts on his recordings, or dares to dream that sound can change the way we see the world. He once said, “Music transcends all barriers.” Today, looking back at his life, we see that he didn’t just play music; he lived it. He took the ancient vibrations of India and wove them into the fabric of the modern world.

So today, on his death anniversary, do not just play his music. Close your eyes. Shut out the noise of the world. And listen to the silence he created—a silence that is full, vibrant, and eternal.

A tribute is, at its heart, a thank you.