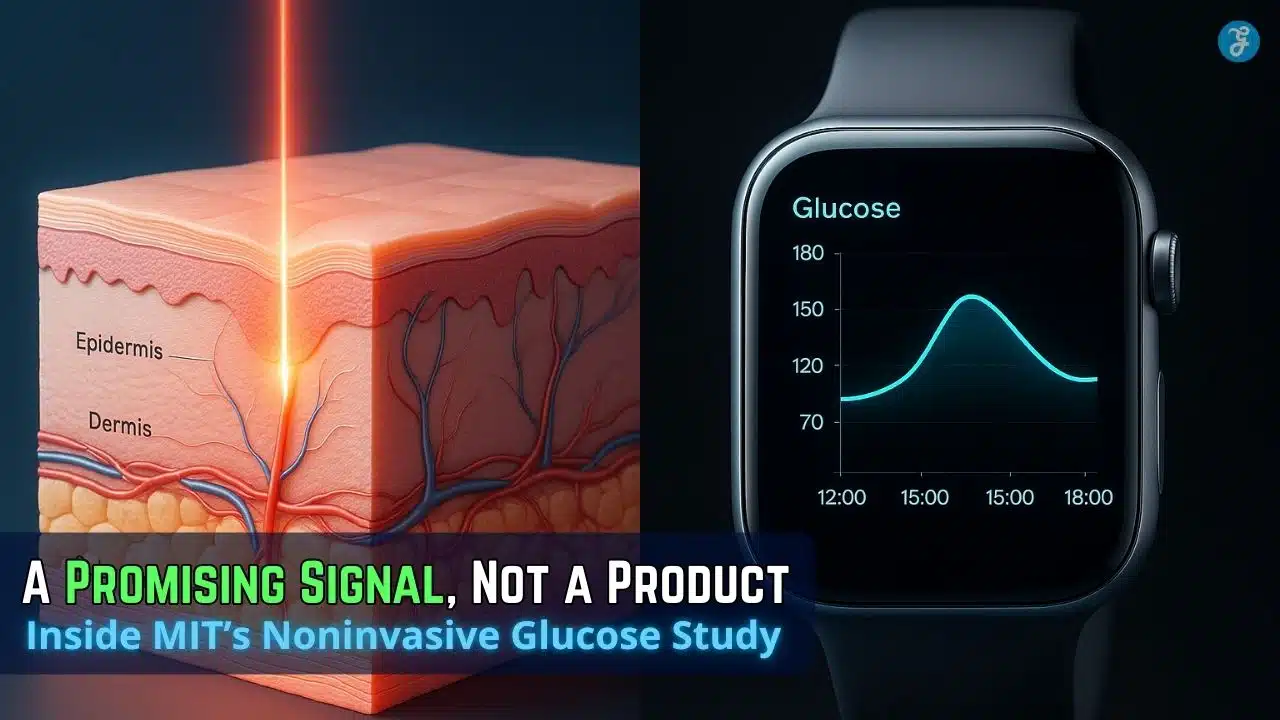

MIT’s latest “noninvasive glucose monitor” is notable because it’s a lab-grade Raman approach redesigned into a compact device and tested head-to-head against commercial CGMs—still early, but it points to a credible path beyond finger-pricks and skin-piercing sensors.

But what if that could all change? What if non-invasive glucose monitoring were no longer a distant dream, but a tangible reality on the horizon?

Researchers at MIT’s Laser Biomedical Research Center believe they’ve found the answer. Their latest breakthrough is a noninvasive glucose monitor that uses light, not needles, to accurately measure blood sugar through the skin. This isn’t just another incremental improvement; it’s a fundamental shift that promises to redefine diabetes management, potentially disrupting a multi-billion-dollar industry and offering a new era of freedom for those who manage this chronic condition.

Why This Matters Right Now

Noninvasive glucose monitoring has been a “holy grail” for decades—and it has also been a magnet for overpromises. In 2024, the U.S. FDA publicly warned consumers not to rely on smartwatches or smart rings claiming to measure glucose without piercing the skin, noting it has not authorized any watch/ring that estimates glucose “on its own,” and warning that inaccurate readings can cause dangerous treatment errors.

MIT’s device lands in that context: it’s not a consumer gadget making vague claims. It’s a research system built on Raman spectroscopy (light scattering that reveals molecular “fingerprints”) and explicitly benchmarked against invasive monitors in a controlled protocol.

At the same time, the need is enormous. The IDF Diabetes Atlas (11th edition, 2025) estimates 589 million adults (20–79) were living with diabetes in 2024, with over USD 1 trillion spent on diabetes that year and 3.4 million deaths attributed to diabetes in 2024.

How We Got Here: Raman’s Promise—and Its Trap

Raman spectroscopy is powerful because it can identify molecules by how they scatter light. But glucose is hard: its signal in living tissue is small and easily buried under stronger “background” signals from skin, water, and other biomolecules.

MIT’s own history illustrates the arc:

- In 2010, researchers at MIT’s Laser Biomedical Research Center (LBRC) showed glucose could be indirectly calculated via Raman signals from interstitial fluid plus a reference blood glucose measurement—but it wasn’t practical as a wearable.

- More recently, the group reported a way to directly measure glucose Raman signals from skin by filtering out unwanted signals using a different illumination/collection geometry.

- The new step: shrink complexity by measuring only a few informative spectral regions instead of collecting an entire Raman spectrum.

This is the key inflection point: many noninvasive efforts fail not because physics is impossible, but because the signal processing, optics, and calibration demands balloon into something too big, fragile, or expensive for real-world use.

The MIT Breakthrough: Core Analysis of How Light Is Cracking the Code

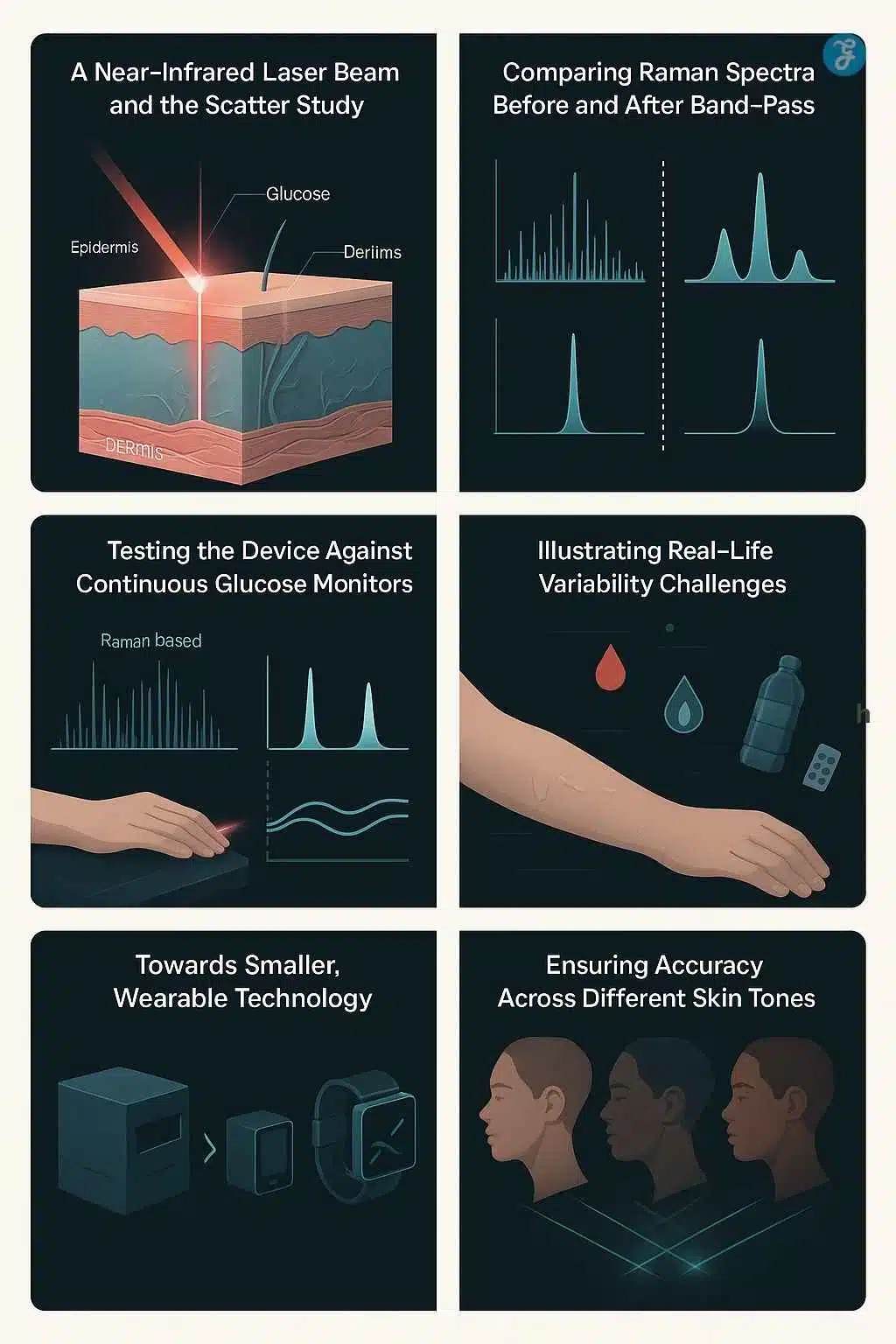

At the heart of MIT’s innovation is a sophisticated technique called Raman spectroscopy. This method, while complex in its physics, can be understood simply: it shines a gentle beam of near-infrared light onto the skin and then analyzes how that light scatters. Different molecules, like glucose, have unique “fingerprints” in how they scatter light.

1) “Band-pass Raman”: reducing the spectrum to what matters

Traditional Raman systems often collect a dense spectrum (MIT notes “about 1,000 bands” is typical). The MIT team reports they can determine glucose using just three bands: one glucose-related band plus two background measurements.

Why that matters:

- Fewer bands can mean fewer optical components, smaller detectors, less power, and faster measurements.

- It also shifts the engineering challenge from “capture everything and compute later” to “capture only what’s interpretable and stable,” which is often what regulators and clinicians prefer—because you can explain what the sensor is actually measuring.

2) Early head-to-head results: matched trendlines vs invasive CGMs (in one person)

MIT describes a clinical study at its Center for Clinical Translation Research in which a healthy volunteer rested an arm on the device while a near-infrared beam measured through a small window. Each scan took a little more than 30 seconds, repeated every five minutes over four hours.

The volunteer drank two 75-gram glucose drinks, creating large, fast glucose swings. MIT reports the Raman device showed accuracy levels similar to two commercially available invasive glucose monitors worn in parallel.

Interpretation: this is an encouraging “physics + prototype” validation, not yet proof of broad clinical performance. One healthy-volunteer comparison can demonstrate feasibility, but it cannot capture the hardest real-world conditions: diabetes physiology, medication effects, dehydration, variable perfusion, motion, sweat, skin products, and day-long wear.

3) Miniaturization roadmap is explicit (and realistic)

MIT says the shoebox-sized version is not wearable, but the group has already built a cellphone-sized prototype and is testing it as a wearable in healthy and prediabetic volunteers. They also plan a larger hospital-linked study that includes people with diabetes.

They also name two hard, credibility-boosting targets:

- Watch-size reduction

- Accuracy across different skin tones

That second point matters because optical systems can behave differently with melanin content and scattering properties. A noninvasive glucose monitor that performs well only on a subset of patients would struggle ethically, clinically, and commercially.

The Bigger Trendline: Invasive CGMs are Improving Fast, Too

Even if a noninvasive device works, it’s entering a market that’s accelerating—not standing still.

CGM adoption is increasingly considered the standard of care for many groups in modern guidelines. The ADA’s 2025 Standards of Care discuss glycemic assessment via A1C, finger-stick blood glucose monitoring (BGM), and continuous glucose monitoring (CGM).

On the product side, the “invasive” category is becoming less burdensome:

- Dexcom reported $4.033B full-year 2024 revenue and highlighted ongoing product expansion (including work tied to longer-wear G7).

- Dexcom’s own materials say its G7 15 Day has FDA clearance and is positioned for extended wear (15.5 days with a grace period).

- Abbott received FDA clearance for two over-the-counter CGM systems (Lingo and Libre Rio), signaling CGM’s push beyond specialist care into broader consumer/primary-care use.

- Senseonics’ Eversense 365 received FDA clearance as a one-year implantable CGM, and FDA review documents describe glucose readings every five minutes over a defined range.

This matters because “replacement” is not just about matching finger-pricks—it’s about beating a moving target where sensors are lasting longer, becoming OTC, and integrating into phones and wearables.

Data Check: What “Matches Finger-Prick Accuracy” Really Means

Finger-stick meters are regulated against accuracy standards. A commonly cited benchmark is ISO 15197:2013, which requires (among other criteria) that at least 95% of meter results fall within ±15 mg/dL of a reference method when glucose is <100 mg/dL, and within ±15% when glucose is ≥100 mg/dL.

For a noninvasive optical system to replace finger-pricks at scale, it typically must show:

- Performance comparable to accepted standards across many users and environments

- Stability over time (no drift)

- Clear labeling around when confirmatory finger-sticks are needed

That’s why the FDA’s 2024 warning is so important: it shows regulators are wary of noninvasive claims that could drive unsafe decisions.

Comparison: What Must Happen Next for True “Replacement”

| Adoption Gate | What has to be proven | Why is it hard for noninvasive optics | What MIT has shown so far |

| Clinical validity | Accurate across diabetes patients, not just healthy volunteers | Diabetes adds meds, variable perfusion, comorbidities, and different glucose dynamics | Pilot comparison in a healthy volunteer; larger diabetes study planned |

| Robustness | Works across skin tones, motion, sweat, and temperature | Optical scattering/absorption varies; motion noise is brutal | Team explicitly targets skin-tone robustness and smaller wearable testing |

| Regulatory pathway | Clear intended use (screening vs treatment decisions) + safety/accuracy evidence | FDA scrutiny heightened by unapproved “noninvasive” products | FDA warns against unauthorized devices; the MIT device is still in pre-market research |

| Economics & workflow | Cost, reimbursement, and integration into care | Competes with rapidly improving CGMs (OTC, longer wear, implantables) | Miniaturization and cost-reduction strategy (“3 bands”) is designed for practicality |

Expert Perspectives: Optimism with Guardrails

The optimistic case

- Raman is chemically specific, which can be a major advantage over indirect proxies (like sweat or generalized optical absorption).

- MIT’s “three-band” approach is a concrete engineering strategy to reduce size and cost.

- The global need is massive: hundreds of millions living with diabetes, with a huge health and economic burden.

The cautious case

- The FDA explicitly warns that inaccurate noninvasive readings can cause dangerous dosing errors and that no smartwatch/ring is authorized to estimate glucose on its own.

- One-person feasibility is not the same as real-world performance across diverse populations and conditions.

- Even “perfect” noninvasive spot checks may not fully replace CGM for patients who rely on alarms, trend arrows, and overnight hypoglycemia detection—areas where CGM has become central to modern diabetes management.

A neutral synthesis: MIT’s work looks like a legitimate research-to-product pathway rather than hype, but the burden of proof for “replacement” is high—and the competitive baseline is rising quickly.

The Road Ahead: Challenges and Milestones to Watch in 2026–2027

While the promise of MIT’s noninvasive glucose monitor is immense, the path to widespread adoption is not without its challenges.

-

Miniaturization and Power: Shrinking a device from “shoebox” to “smartwatch” is an engineering marvel in itself. Raman spectroscopy, even when refined, requires specific laser power and optics, which demand battery life and space. Balancing these requirements within a sleek, comfortable wearable is a significant hurdle.

-

Skin Tone Variability: Optical sensors can be affected by melanin, the pigment in skin. Darker skin tones absorb more light, which can interfere with signal quality. Rigorous testing across diverse populations and Fitzpatrick skin types will be critical to ensure equitable and accurate performance for everyone.

-

Regulatory Approval: Any new medical device, especially one that directly impacts critical health management like glucose monitoring, must undergo stringent regulatory approval processes (e.g., FDA in the US, CE Mark in Europe). This involves extensive clinical trials to prove both safety and efficacy, a process that can take years and significant investment.

-

Cost and Accessibility: While eliminating recurring sensor costs offers long-term savings, the initial purchase price of a high-tech noninvasive glucose monitor could be a barrier for some. Ensuring affordability and insurance coverage will be crucial for equitable access.

The Future of Diabetes Management: Empowering Patients

Despite these challenges, the future envisioned by MIT’s noninvasive glucose monitor is undeniably bright. Imagine a world where a continuous, painless glance at your wrist provides the data you need to manage your diabetes effectively, empowering you with constant awareness and freeing you from the daily burden of needles.

This technology has the potential to:

-

Improve Adherence: Remove a major barrier to consistent monitoring.

-

Enhance Glycemic Control: Provide more data points for better management decisions, leading to fewer complications.

-

Reduce Healthcare Costs: Potentially lower expenses for patients and healthcare systems over time by eliminating disposable components.

-

Foster Innovation: Open new avenues for integrating glucose data with other health metrics and AI-driven predictive insights.

The research emerging from MIT represents more than just a scientific advancement; it’s a beacon of hope for millions. While we are likely still a few years away from seeing this device on store shelves, the December 2025 progress indicates that the era of the needle may finally be drawing to a close. The revolution of non-invasive glucose monitoring isn’t just coming—it’s now within our grasp, promising a healthier, more comfortable future for those living with diabetes.

Frequently Asked Questions about Noninvasive Glucose Monitor

Is the MIT non-invasive glucose monitor available to buy right now?

No, not yet. As of late 2025, the device is in the advanced prototype stage. Researchers have successfully shrunk it from a desktop size to a portable “cellphone” size, but a consumer-ready smartwatch version is likely still 3–5 years away from hitting the market.

How accurate is this light-based sensor compared to traditional CGMs?

In clinical pilot studies, the MIT sensor demonstrated accuracy comparable to current FDA-approved invasive sensors. By using a novel “off-axis” light collection method, it filters out the noise that plagued earlier optical sensors, providing reliable data.

Will this device work on all skin tones?

This is a key focus of ongoing development. Historically, light-based sensors have struggled with darker skin tones because melanin absorbs light. The MIT team is actively working to ensure the “band-pass” filtering technology is robust and accurate across all Fitzpatrick skin types before commercial release.

How does this differ from the “Smart Tattoos” MIT developed previously?

The “Smart Tattoo” (DermalAbyss) project used color-changing ink injected into the skin. This new 2025 sensor is completely different; it is pure hardware that sits on top of the skin and uses laser light to read glucose levels without putting anything inside the body.

Will it require calibration with a finger prick?

Likely, yes—at least initially. Most non-invasive technologies still require an occasional “baseline” reading from a standard blood glucose meter to ensure the optical sensor stays calibrated, though the goal is to eventually eliminate this need.

Final Thoughts: Will It Replace Finger-Pricks?

If the larger trials confirm accuracy across diverse users and conditions, noninvasive glucose monitoring could reduce finger-pricks dramatically for many people—especially for spot checks and routine monitoring.

But full replacement is harder. In the medium term, a more likely outcome is a hybrid world:

- noninvasive optical devices for comfortable checks and broader access,

- minimally invasive CGMs for high-risk users who need continuous trends and alerts,

- finger-sticks as a backup/confirmation method when readings don’t match symptoms—consistent with the safety mindset regulators emphasize.